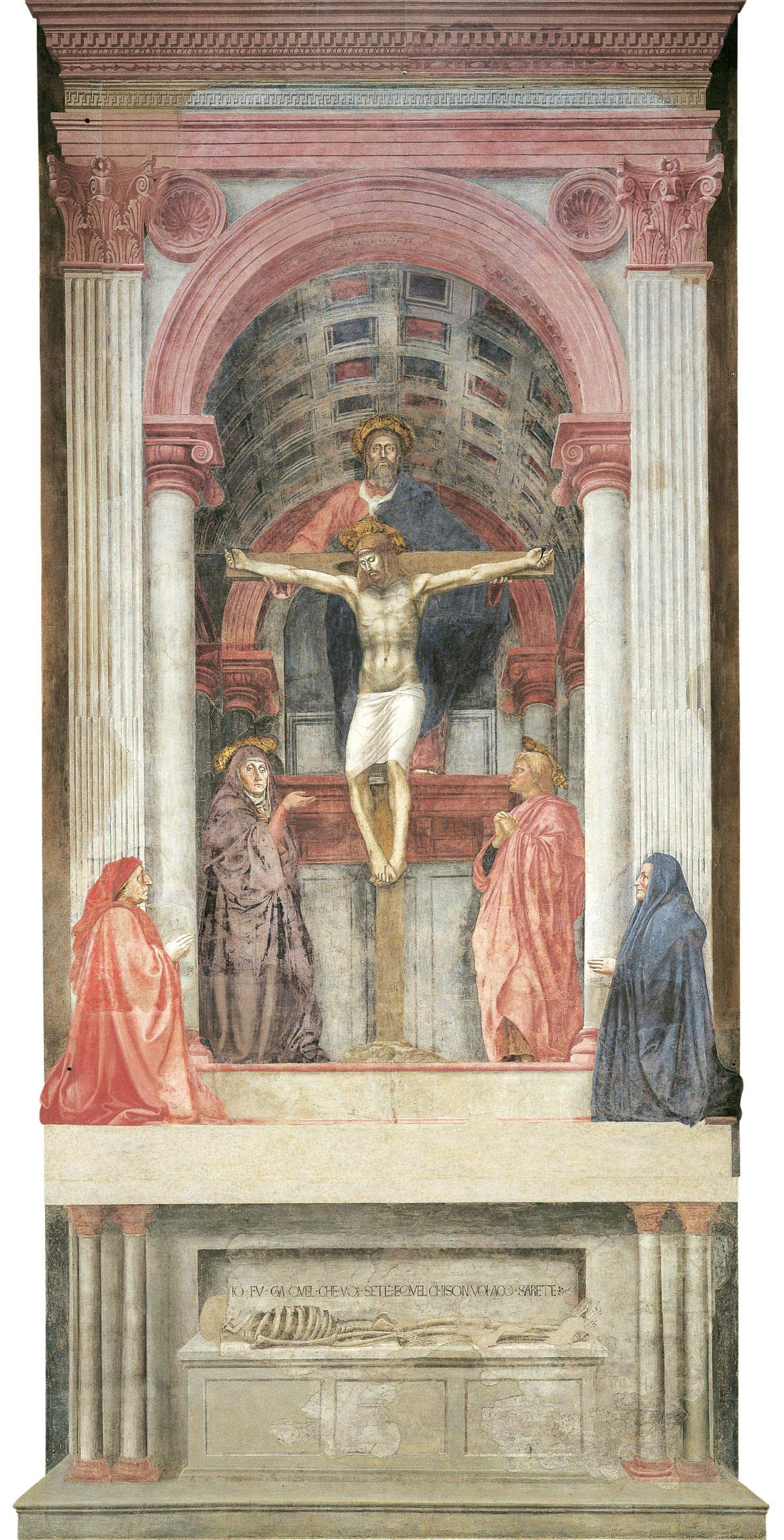

On the wall of the third arch of the left aisle of the Dominican basilica of Santa Maria Novella in Florence is a fresco that is considered the programmatic manifesto of the new Renaissance painting. It is the Trinity, the last work created by Masaccio (Tommaso di Mone Cassai; Castel St. John’s, 1401 - Rome, 1428) in his brief but decidedly intense activity as a painter, interrupted by his untimely death in Rome at the age of only 26. According to Vasari’s Lives, Filippo Brunelleschi on hearing of his death is reported to have said, “We have made in Masaccio a very great loss,” testifying to the importance he was already being accorded in the Florentine milieu contemporary with him. Brunelleschi and Donatello were the artists of reference for the young Masaccio. In particular, in the work for Santa Maria Novella the model of reference is Brunelleschi himself: in fact, the centrality that the representation of space modeled according to Brunelleschi’s laws of perspective takes on in this painting is manifest, so much so that some scholars have speculated on his direct involvement in the creation of this work.

Masaccio arrived in Florence from his place of origin, present-day St. John’s Valdarno, by 1420. At that time the predominant painting taste in Florence was still linked to the late Gothic world with Lorenzo Monaco, documented until 1422, receiving the most important commissions in the city. It was precisely in 1420 that what was considered the most prestigious Italian painter of the time, Gentile da Fabriano, arrived in the Tuscan city; by 1423 he produced a masterpiece such as theAdoration of the Magi panel commissioned by the wealthy banker Palla Strozzi. Masaccio embarked on a totally different direction, taking painting to revolutionary new heights in just a few years and contributing, along with Donatello and Brunelleschi, to laying a solid foundation for Renaissance art.

The fresco in Santa Maria Novella is of great importance not only from a stylistic and figurative point of view, but also from a theological one. In fact, Masaccio is asked to depict the dogma of the Trinity, instituted during the Council of Nicaea in 325, which states that Father, Son and Holy Spirit are one reality. It is plausible that for the design of a painting with such a complex iconography so dear to the Dominican order a theologian, perhaps from within the convent itself, was involved, but no documentation is known about this. One name that has been proposed is that of Friar Alessio Strozzi, whom Masaccio might have known through Brunelleschi.

References to this work can already be found in Prevasarian sources and then in Vasari himself, who praises it both for the composition of the figures, but especially for the illusionistic architectural perspective: “What is beautiful in it, besides the figures, is a half-barrel vault pulled into perspective, and divided into squares full of rosettes that diminish and escort so well that it seems that that wall is pierced.” In 1570 Giorgio Vasari, called to make some changes in the church on Sunday following the Counter-Reformation, produced a panel for the new stone altar dedicated to Our Lady of the Rosary, sponsored by Camilla Capponi, which went to completely hide Masaccio’s work. The fresco thus remained hidden for centuries and was rediscovered only in 1861. It was therefore detached with an intervention by restorer Gaetano Bianchi and transferred to the counterfacade wall of the basilica.

In 1951, under the direction of Ugo Procacci, the lower part of the fresco, depicting Death, was found in its original position. On that occasion it was understood that Masaccio created the Trinity on the surface of two earlier frescoes, plugging part of a window above. It was not until 1952, following the discovery of Death, that the fresco was relocated to the wall on which it had been created by the painter. Restorer Leonetto Tintori was able to identify the days of execution, twenty-seven, and to verify how much of the original remained in the fresco: following the nineteenth-century discovery, in fact, some repainting had been done. From the study of the days it emerges how the painter paid particular attention to the architectural details, showing how this was an aspect of absolute importance to him.

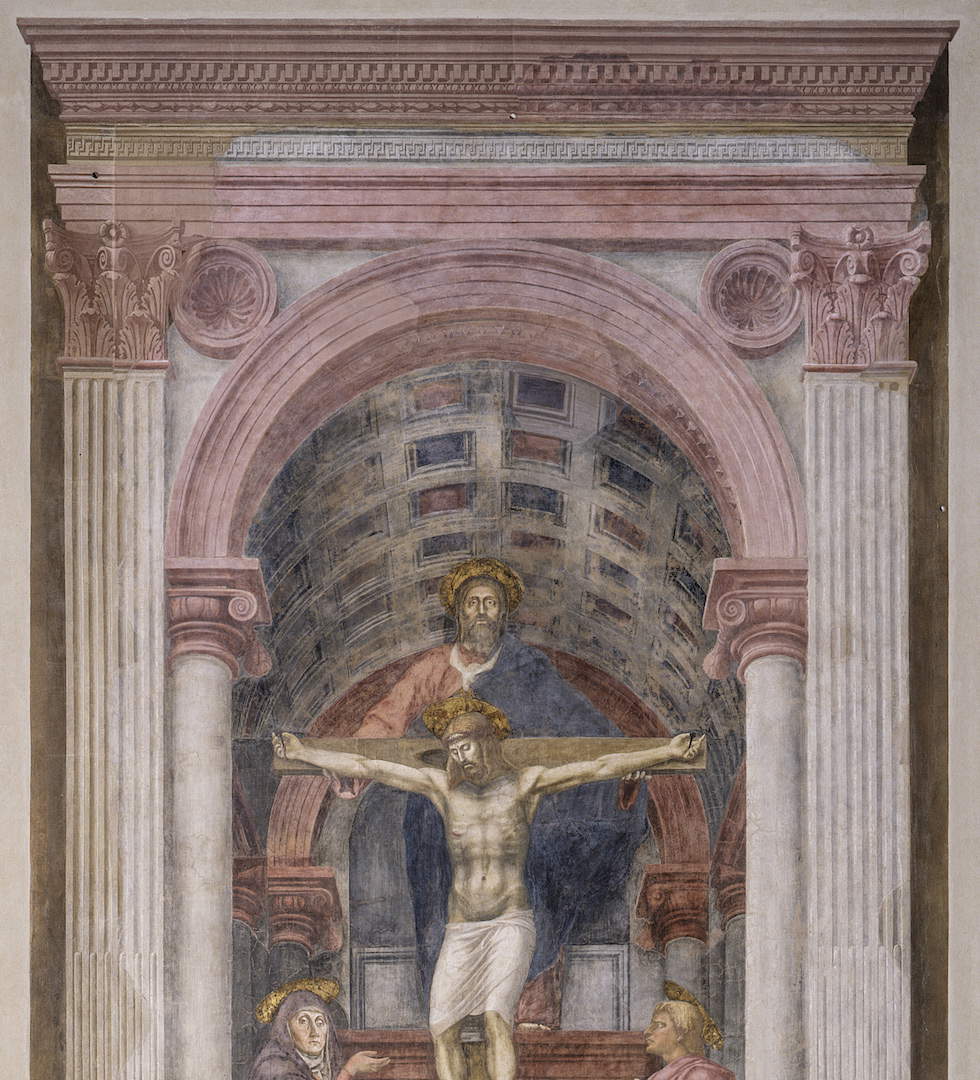

The entire scene is imagined and depicted inside a chapel, conceived according to the architectural models proposed by Brunelleschi, who retrieved elements of classical architecture, particularly Roman architecture. The entrance to this chapel is decorated with fluted pilasters ending in a Corinthian capital, in front of which are two kneeling figures, in which the patrons can be identified. A round arch supported by columns with Ionic capitals introduces the actual space of the chapel, surmounted by a splendid barrel vault decorated with coffers colored in blue and red. Compared to Brunelleschi’s actual architecture, Masaccio highlights with the use of red color some architectural elements, such as the arch and lintel, which are often made of pietra serena stone in Brunelleschi’s work that is left exposed. The entire composition is drawn using central linear perspective, a system through which three-dimensionality can be depicted on a two-dimensional plane. The conceptual authorship of linear perspective rests squarely with the genius of Brunelleschi, who identified a scientific method for rationally mastering the surrounding reality. The entire painting is designed with respect to the viewer’s vision, which is aligned with the plane on which the patrons are painted. By following the lines of this perspective construction, it is possible to reconstruct the section of this chapel and be able to understand more clearly the different levels of depth that Masaccio imagines for this space. Moreover, by observing the arrangement of the figures, particularly their heads, one realizes that they are arranged along the perimeter of an imaginary triangle, which considering the proposed iconography, reinforces its meaning through the symbolic presence of the number three. It is possible to draw another hypothetical triangle that has the faces of Christ and the patrons as vertices. With close observation, one can still identify the lines engraved on the surface used for perspective construction.

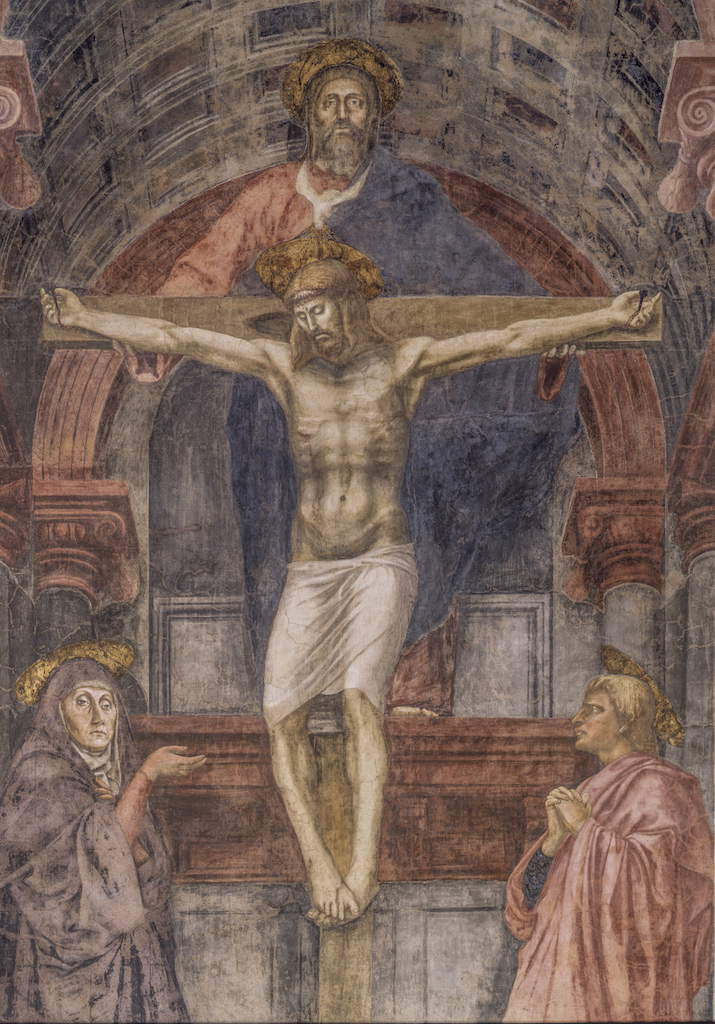

The Trinity fresco has a vertical development and three levels can be identified. In the lower area, laid on a sarcophagus that emerges from a niche, is a skeleton, a depiction of Death, accompanied by an inscription that reads "I WAS ALREADY WHAT YOU SET, AND WHAT I AM YOU ALSO WILL BE." It is a memento mori, a warning to man about the transience of earthly life. In the middle level, on either side of the composition and kneeling at the table of this painted altar are the patrons. It is not possible to state with certainty the identity of these two people: one of the main hypotheses holds that they could be Domenico Lenzi and his wife, who in 1426 were buried under the floor of the church in the area facing the work. Another hypothesis sees the possibility that the patron may have been a member of the Berti family. While we are not yet able to give them a certain name, we can say, however, that Masaccio produced two extraordinary portraits of these two people, among the most realistic in all of Renaissance art. The painter takes extreme care in the characterization of their physiognomies and expressions. Following the perspective lines, on a level set back from that of the patrons are the mourners on either side of the Cross. The Virgin is not depicted in an attitude of sorrow, but her impassive gaze is turned toward the viewer, while with her right hand she points toward the group of the Trinity, as if to introduce us to meditation, acting as a conduit between the viewer and the dogma depicted. John, too, is not withdrawn into his own grief, but while manifesting it on his face, he has his gaze turned toward the cross.

The group of the Trinity consists of God the Father holding, with arms wide open, the arms of the cross on which the Son was crucified, while a dove, symbol of the Holy Spirit, glides toward Christ, being right between his head and the Father’s face. Masaccio for this representation was inspired by the iconographic model of the Throne of Grace, popular in Florence at the end of the 14th century, with the difference of presenting God the Father standing and not seated, precisely, on a throne.

Masaccio, in order to make the representation consistent and realistic, makes a revolutionary choice: all the characters are depicted with the same dimensions, without distinction between the sacred and profane dimensions. On the contrary, the two patrons appear slightly larger to the eye of the observer because they are in the foreground compared to the two mourners and the group of the Trinity, positioned within the space of the chapel. This is a disruptive proposal that creates a clear break with medieval depiction: in fact, the symbolic proportions, which Piero della Francesca would still use for certain iconographies, are subdued to the rational construction of the scene. It is precisely the perspective layout that is the real protagonist of this fresco. All the characters in this painting assert their presence in space through their imposing three-dimensional volumes, rendered through an extraordinary use of chiaroscuro, which makes these figures resolutely majestic. They appear, wrapped in sumptuous draperies, as imposing statues. The realism proposed by Masaccio is truly shocking, and the use of light decisively enhances their forms. Again, there is no distinction between sacred and profane dimensions, because all the characters are equally concrete within the space.

It is not only the dogma of the Trinity that is depicted by Masaccio in the Santa Maria Novella fresco, but also the path that man is led to take in order to achieve Christian salvation. Starting from the bottom, the skeleton represents earthly life and its transience. Man, by his mortal nature, through the exercise of prayer, in which the two kneeling patrons are engaged, and the intercession of the saints (the Virgin and St. John), can reach God and eternal life

This sophisticated fresco, which closes Masaccio’s short career, is one of the landmark works of Western art and is considered one of the emblems of the humanistic culture that developed in Florence in the early fifteenth century. Through the use of linear perspective, Masaccio was able to give this painting an unprecedented depth, opening not only, illusionistically, a space in the wall, but also new horizons for Renaissance painting.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.