A manuscript with a thousand years of history. The psalter-innary-collectary of Farfa Abbey.

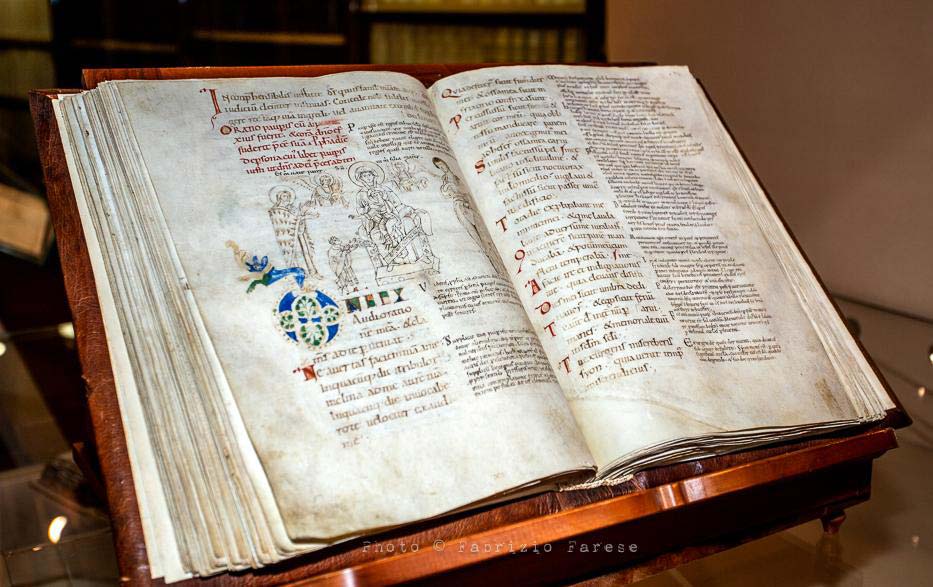

A manuscript that has spanned a thousand years of history and has come down to us almost intact: this is Manuscript AF. 281 preserved at the State Library of the National Monument of Farfa, the rich library of the Abbey of Farfa, which is located near Fara in Sabina, among the verdant ridges of the Sabine Mountains, which separate Rome from Rieti. It is a parchment manuscript dating back to the 11th century, which is now on display in a case in the Farfa Library and is therefore visible to the public, precisely because of its uniqueness and distinctiveness. It is a composite manuscript, made up of 183 membranous folios, which contains within it several works: the most substantial part is that formed by folios up to 110, which contain a psalter, that is, the complete collection of 150 psalms, distributed along the days of the week so as to be recited according to the canonical hours of the liturgy.

Scrolling through the text, folios 110 to 119 contain the Old Testament Canticles, with glosses, that is, commented on with notes in the margins, while folios 119 to 123 continue with the New Testament Canticles and some prayers. Two sheets, 123 and 124, contain some litanies of the saints, while from 125 to 132 some prayers can be read. The part from folio 133 to 159 is by consistency the second longest in the AF manuscript. 281: this is a hymnal, a collection of religious hymns. From folio 159 to 165, it is possible to find some biblical hymns from the Temporale and the Santorale (these are two times of the liturgical year: the Temporale includes Advent, Christmas, Lent, Easter and all Sundays of ordinary time, while the Santorale includes the days on which saints are celebrated), while the readings from the Temporale and the Santorale occupy folios 165 to 182. It ends with the last two folios containing the Orationales totius anni circuli (the last folio is mutilated, however).

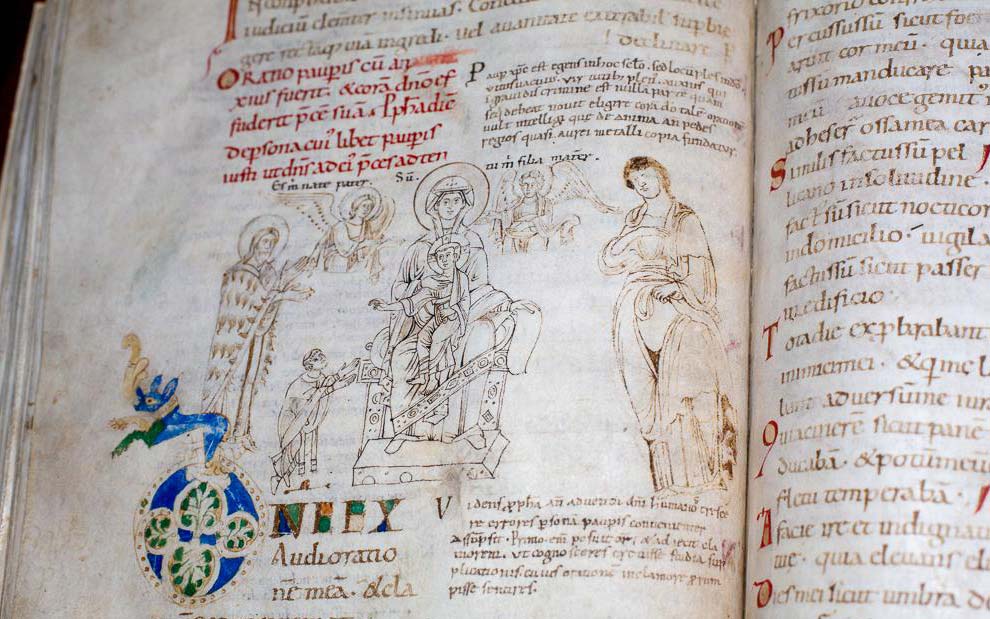

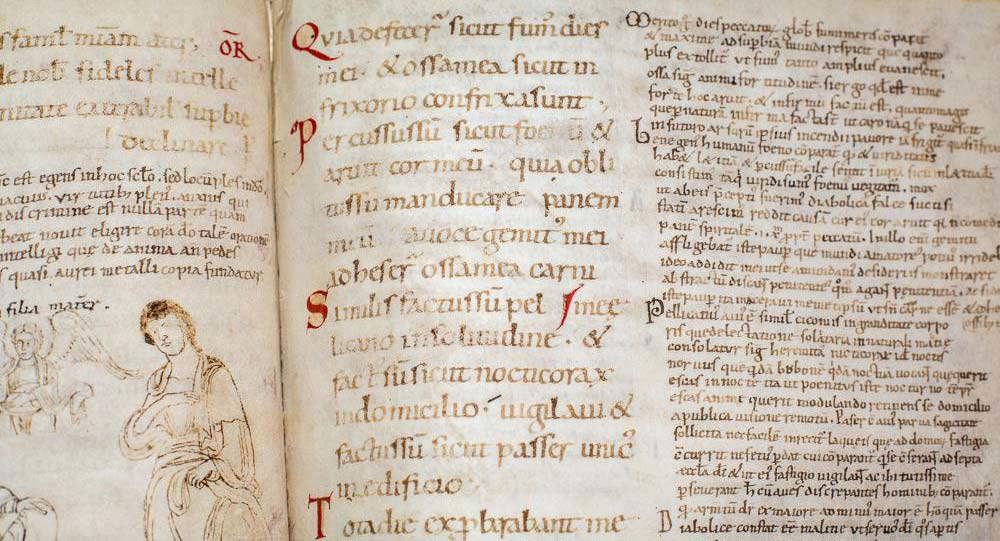

The manuscript was compiled at two different times, between the end of the 11th and the beginning of the 12th century: scholars have in fact found a moment of transition between two different hands between folios 143 and 144, even though both used the same script, the Romanesque minuscule, a particular form of Carolingian script widespread in and around Rome. After the end of the 8th century, the Carolingian script experienced a wide diffusion and great fortune, so much so that it was still used in the 11th century: it was in fact a very fast and practical script, which had allowed it to successfully replace all previous scripts precisely because it was much more performant. The Romanesque minuscule was a local typification of the Carolingian script, as many developed: it is distinguished by its relatively large letters sloping to the right, its rather irregular alignment, and the squared design of the letters, which may, however, have some undulations in the shafts.

Looking at the text one can see that it has undergone several additions along the centuries. For example, on the first sheets one can see a dedication to the reader dated “XV calend. decembris 1755.” On the first sheet, however, it is possible to read a later addition that recites, “Desunt psalmi xx per totum cum eorum expositione, et dimidium Psalmi xxi sequentis.” Someone at some point also added the dating, again on the first sheet: “Codex XII Saec.” The last sheet also reads “Huius codici desideratur finis.” The work was certainly produced in the scriptorium of Farfa Abbey, and this information can be inferred from some details found in the text: the litanies, in fact, celebrate some saints, such as the martyrs Valentinus, Hilary and Getulius, whose remains between the 9th and 10th centuries were transferred to Farfa, or some monks such as Equitius, Columbanus and Libertinus (hymns in their honor are found in other Farfa litanies), and again the virgins Victoria and Anatolia, who are also linked to the abbey of Farfa. Moreover, as scholar Paola Supino Martini has shown, some technical features of the manuscript, namely the type of writing and decoration, and the sequence of hymns, prayers, melodies and glosses, are comparable to the Chigi manuscript C.VI.177 preserved at the Vatican Library and containing the “Breviary of Farfa.” To date, the psalter-innary-collectary is the only “Farfense” manuscript of those preserved in the abbey, since the ancient heritage of the library of Farfa has been dispersed over the centuries. From the analysis of the glosses we are certain that manuscript AF 281 was used continuously at least until the 13th century. In 1972 it was finally stolen, along with other manuscripts, from the abbey: however, it was found and in 1975 underwent restoration in the book restoration laboratory of the Abbey of Cava (on that occasion the stamp of the restoration laboratory was affixed, particularly in the rear guard sheet: guard sheets are those inserted between the cover and the written sheets, with protective functions).

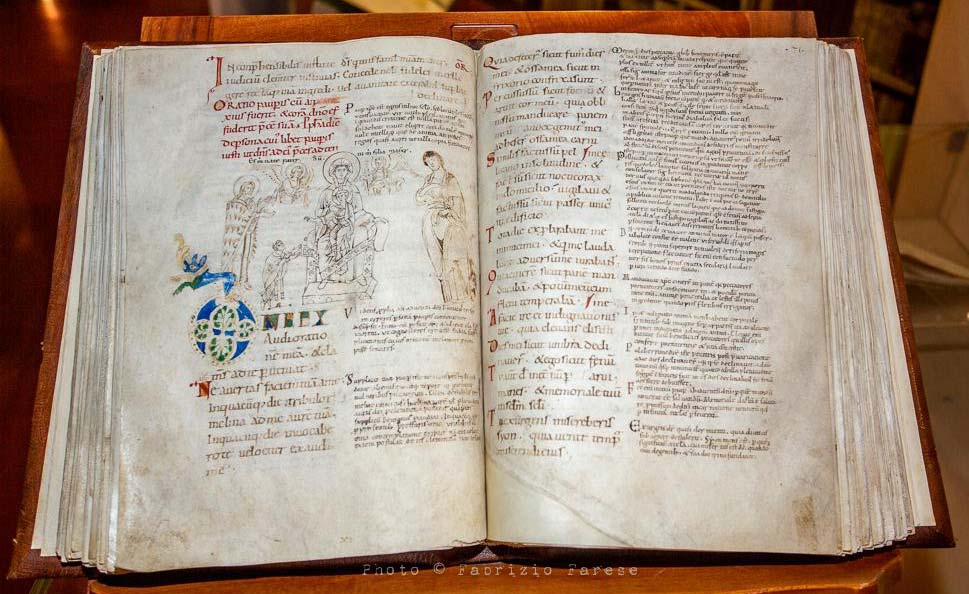

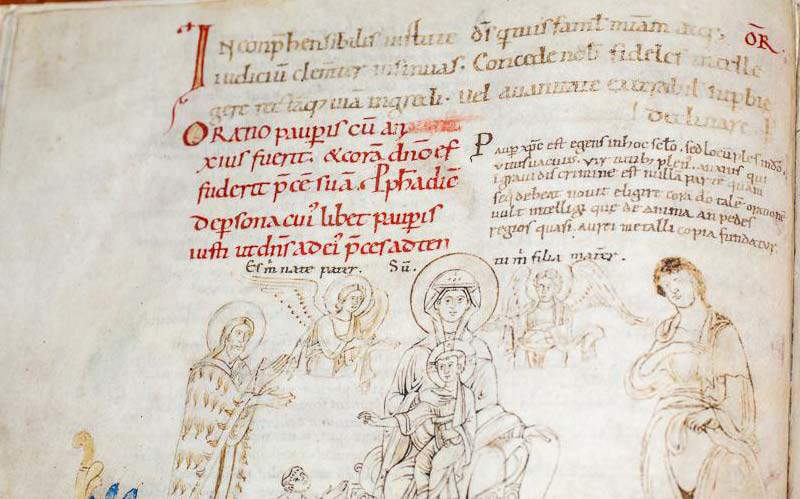

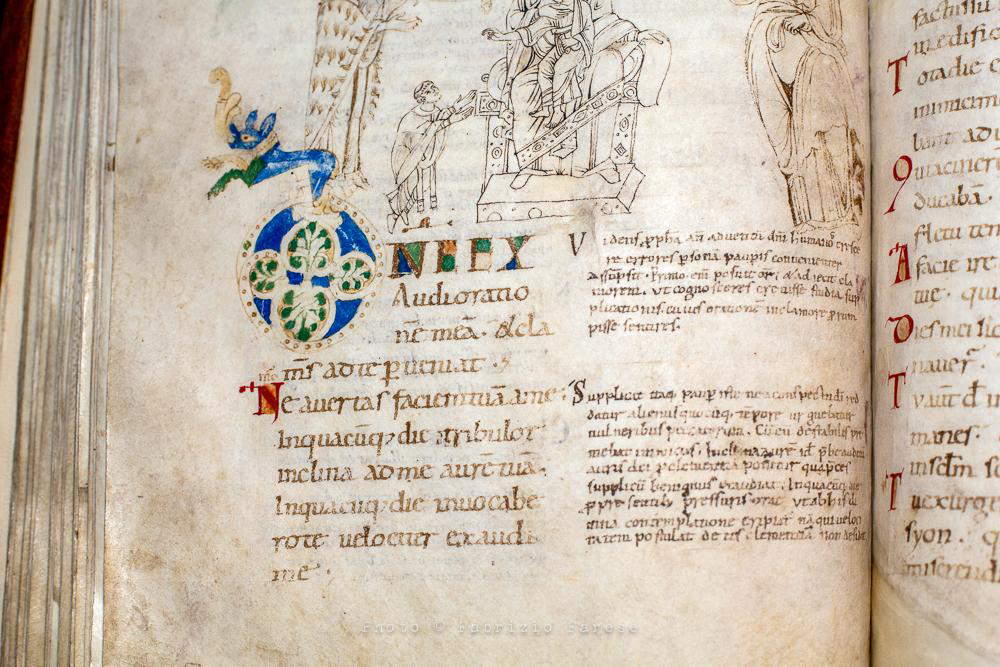

Manuscript AF. 281 is also distinguished by the uniqueness of its decorations: there are several decorated initials, with phytomorphic, zoomorphic, phytozoomorphic, and anthropomorphic motifs (note, for example, a peacock on folio 2v, an animal head on folio 7v, a figure with a halo in the act of blessing on folio 65v, and an animal biting on folio 177r). The most important and singular image, however, is found on folio 70v, where, at Psalm 101, and above a splendid “O” in dark blue and made with lapis lazuli (one of the most expensive, a sign that the manuscript must have been of extreme importance to the abbey) we see an enthroned Madonna and Child, flanked by two angels and Saints John the Baptist and John the Evangelist, while at the bottom we see a monk in the act of adoring the Virgin. This is a problematic image, both in terms of identifying the subject and in terms of its dating.

The most probable hypothesis is that it was added at an unspecified later time over a portion of deleted text (in fact near the illustration some elements of the text seem to be missing), and that in addition the figures appearing on either side of the Virgin were executed by different hands, both because of obvious stylistic differences (softer draperies, different facial types) and because the ink is different. Moreover, it is plausible, given also the precision of the stroke, that the image traced by the anonymous artist who executed this figure is a reproduction of the Madonna of Farfa: also known as the Madonna of Acutianus from the name of the mountain on which the first seat of the abbey of Farfa stood, it is a Byzantine icon, which survives today in fragmentary form (with even 19th-century remakes), preserved in the abbey church of Santa Maria di Farfa. The face of the Virgin that appears in the illustration is very similar to the one that survives in the image that can be seen in the church today: if so, it would be an attestation of what the intact image of Our Lady of Farfa must have looked like in ancient times. Specifically, this would be a Madonna of the iconographic kyriotissa, “lady” type, which sees her depicted enthroned in basilissa (“queen”) dress, while showing the Child, who in turn was depicted in the act of blessing. A solemn, frontal image, it experienced widespread use from the earliest centuries of Christianity.

In any case, the manuscript AF. 281 is not only important for its antiquity and for its significant image of the Madonna and Child, but also as a remarkable testimony to life in the abbey of Farfa: the Farfa monks, in fact, still recite the prayers contained in the manuscript, which over the centuries have undergone some formal modifications, but which have not altered their content. A rituality that has continued for a thousand years, and the manuscript is its most concrete and eloquent witness.

The State Library of the National Monument of Farfa.

The abbey of Farfa arose between the fifth and sixth centuries, and its library probably originated at the same time. The earliest certain records, however, date from the mid-8th century: the library, in particular, was fed by the conspicuous output of the abbey scriptorium. Successive abbots over the centuries greatly increased the library collection. In 898 there was an initial dispersal of the volumes, with the evacuation of the abbey due to Saracen attacks: the monks divided into three groups, and some of the books were moreover destroyed during a fire set during the Saracen occupation. It was in the 10th century, with the return of the monks to Farfa, that the library began to be reassembled in its location. The real revival, however, came with Abbot Hugh I, who, among other things, introduced the Cluniac reform at Farfa in 999, under the pontificate of Sylvester II. Hugh enriched the library with many of his works, and under his rule the scriptorium attained its greatest importance, so much so that most of the codices that have come down to us belong to this period, in which Farfa’s Romanesque script was also precisely characterized.

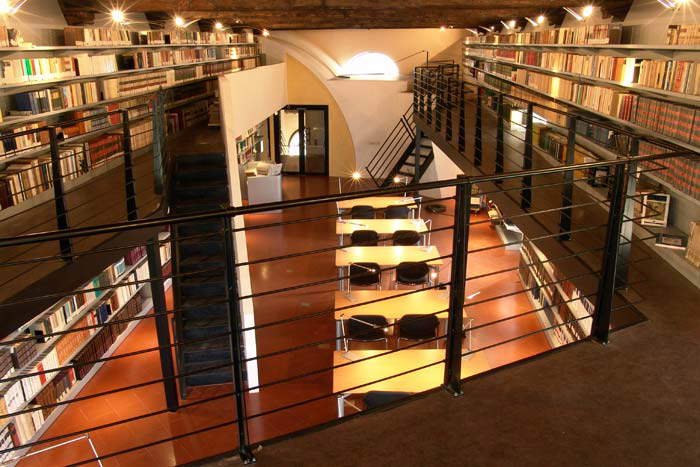

With the transition from Imperial Abbey to direct rule of the Roman Curia after the Concordat of Worms and the consequent appointment of commendatory abbots, Farfa’s fortunes in the 12th century began to decline. The library also suffered, with sales and thefts of codices. The final dispersion of Farfa’s library holdings began at this time and continued in the following centuries, so much so that in 1400 Pope Boniface IX forbade the removal for any reason of the “writings” belonging to the monastery and appointed his nephew, Cardinal Francesco Tomacelli, commendatory abbot to revive the abbey’s fortunes. The dispersion slowed but did not cease, and the situation became dramatic after the Napoleonic suppression in 1798, when almost all the books had by then left the abbey, and even the movable property was put up for sale. In 1861 the territory of Farfa was annexed to the Italian state and all the monastery’s assets were forfeited. These included 1,750 volumes of the Farfa library, which ended up in the Vittorio Emanuele II National Central Library in 1876, while the archival material (from the 17th to the 19th centuries) was placed in the State Archives in Rome. The monastery remained virtually abandoned for several decades until, in the early 20th century, a German-born monk, Don Bruno Albers, took charge of the library, managing to recover many archival papers, providing for the purchase of many works and leaving a substantial personal library on historical-religious subjects as a gift to the abbey. In 1920, a group of monks took up residence in the abbey again, and the library began to flourish again, acquiring works and bibliographic holdings, with work continued in the following decades. A first summary cataloguing was carried out in 1943 by Abbot Don Basilio Trifone, when the Library was located in the corridors of the upper floor of the abbey: a total of 10,300 volumes, a hundred journals and about fifty miscellanies. The library, along with ten others in Italy, is now part of the special category of Libraries attached to National Monuments. The official inauguration took place on February 9, 1964.

Today the Library of Farfa possesses about 450 manuscript volumes from the 10th to the 20th century, about 200 of which are archival in character and 17 from the medieval period (the only one considered “autochthonous” is the psalter-innary-collectory AF. 281), 270 parchments dated between the 12th and 18th centuries (including the copy of the Annales sacri et imperialis Monasterii farfensis compiled by the monk Gregory Urban in the years 1643-46 for Abbot Gregory Coppini and dedicated to him), 50 parchment fragments from the 11th to 17th centuries, about 50,000 printed volumes, a historical collection of about 8,000 volumes, 46 incunabula, 581 cinquecentine, 200 titles of Italian and foreign periodicals. Finally, in addition to the state-owned library holdings, the library houses in the magazine room the Cremonesi Fund consisting of about 2,000 volumes ranging from the 15th to the 20th century. The fund, belonging to the Foundation of the same name, which also owns the hamlet of Farfa, consists of volumes from the library of Filippo Cremonesi, a senator and governor of Rome during the Fascist period. The section, along with a large number of photos related to the senator’s public and private activities, is available to users thanks to the availability of the Filippo Cremonesi Foundation.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.