A love that will last for eternity: Raphael and the Fornarina

Throughout the ages the subject of the feeling of love has been deified, spiritualized, desired and sometimes even possessed; love has been the source of sighs, torments, joys and passions. For all that, it has always been the inspiration of writers, poets and artists who have sought to imprint, on paper through words and on canvas through painting, that myriad of sensations that love unintentionally arouses, for the only thing certain about love is that it invades us without explanation, unconditionally.

We are referring to that pure feeling that makes us feel butterflies in our stomachs and our minds in the clouds: put like that, it would sound like anvviety, but unfortunately, especially nowadays, it is not. However, if we think of Dante and Beatrice, Laura and Petrarch, Leopardi and Silvia, Romeo and Juliet, Cupid and Psyche, and so many other literary and artistic couples, we realize that these, from ancient times, have fascinated us, leading us more to desire to know the endless stories of love that have pervaded the worlds of literature and art. Here we try to analyze one of them.

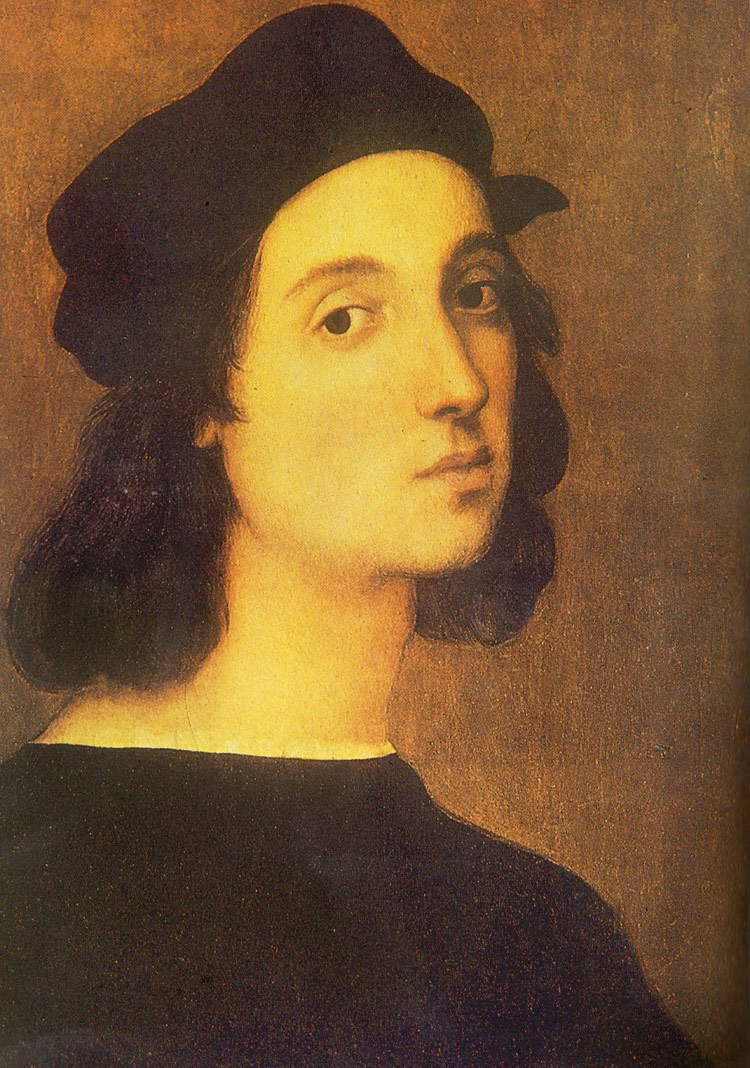

He is one of the greatest artists of the Renaissance, known throughout the world. Born in Urbino in 1483, he is the son of another famous painter, Giovanni Santi, who worked at the Montefeltro court. He was a pupil of Perugino and a friend of Pinturicchio; after traveling between Florence and Siena, he moved to Rome, where he would create his greatest masterpieces at the behest of Pope Julius II and Pope Leo X. This is Raphael Sanzio.

|

| Raphael, Self-Portrait (c. 1504-1506; oil on panel, 47.5 x 33 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

She is the daughter of a Trastevere baker, so beautiful that as soon as Raphael sees her he is thunderstruck. It is no coincidence that she would become muse for some of his most famous paintings: the so-called Fornarina, kept at the Galleria Nazionale dArte Antica in Palazzo Barberini in Rome, and probably also the Velata, kept at the Galleria Palatina in Florence. She is Margherita Luti, a young woman of Sienese origin, daughter of Francesco Luti, a baker in Rome. Her nickname Fornarina derives precisely from her father’s trade.

|

| Raphael, The Fornarina (1518-1519; oil on panel, 87 x 63 cm; Rome, Palazzo Barberini, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica) |

In a note to Raffaello e la Fornarina, a canto written by the Romantic poet Aleardo Aleardi and published in 1858, we read that the Fornarina’s house answered with its picciol orto in sul Tevere, da quella banda, verso Ripa grande, dove il fiume lambe le rotte pile del ponte Sublicio: poco discosta dalla Chiesa di S. Cecilia, alle ultime pendici del Gianicolo. There Sanzio saw the beautiful transteverina for the first time, and he was enkindled by it, and of that moment he preserved the memory in one of his Sonnets, thrown down good-naturedly. Artists since then knew all about it.

The sonnet in question, written by Raphael himself behind one of his drawings of three of his figurines, reads thus: Un pensier dolce è rimembrare, e godo / di quellassalto, ma più provo il danno / del patir, chio restai, come que channo / in mar perso la stella, se il ver odo. / Or tongue to speak untie the knot / to tell of this unusual deception / that amor made me for my grievous affliction; / but he more I thank, and she praise. / Lora sesta was that loccaso un sole / had made, and the other scorse il loco / atto più da far fatti che parole. / But I remained nevertheless won to my great fire / that torments me, ché dove luom suole / desïar di parlar, più riman fioco.

Aleardo Aleardi, in his composition, poetically depicts the first meeting between the two young people and in particular the moment when Raphael sees Margaret and is immediately dazzled: Il sapiente sguardo / indagator de la beltade affisse / il cavaliero lungamente in quella / grazia di Dio: notare la superba / leggiadria de le forme, e il crine, e il labro / tumidetto e le molli ombre e la varia / ingenuità de le virginee pose. / Ondei fu vinto. With broken leaps his heart / beat: the river, the trees, the walls / spun around his / giddy pupils: he feria of a hundred / indistinct rattles a tinny, and the palm / quivering burned to him, like a flame / in the wind. Finally he roused himself, and said / involuntarily “ o Fornarina! ”. / At that instant swiftly he turned / and blushed the beautiful crëature; / he drew his foot from the deep all oozing. / And the long rays of the black eyelashes / veiled the modesty of his cheeks.

The poet imagines the beautiful Fornarina graceful in form and pose, fine and harmonious in her features, with fairly full lips, beautiful hair, shy, naive and demure. We seem to be looking at the famous painting made by Raphael Sanzio, between 1518 and 1519, in which she is depicted lamata. In the 1686 inventory, after the death of Maffeo Barberini, the work is described as follows: a panel portrait of a woman, holding one hand to her breast and the other between her thighs, naked, with a red cloth. The pose of the hands, one resting on her lap, the other on one breast, recalls the demure Venus of classical statuary: the woman covers herself with a transparent veil in a demure gesture, although the eye of the observer is directed toward what the figure would like to remove from view. Her black hair appears gathered in a long gold and blue drape knotted at the nape of her neck and embellished with a bead adorning her head. The face is regular with large dark eyes, a rather fleshy mouth, and slightly flushed cheeks. The pearl, present in both the Fornarina and the Velata, would refer to the girl’s very name: Margherita is in fact derived from the Greek word margaritès, meaning pearl, gem, although in the Middle Ages it took on the customary lacception of a botanical element. Therefore, the small ornament on the head would be a further tribute to the beautiful Margherita Luti.

|

| Raphael, La Velata (1515-1516; oil on canvas transposed from panel, 82 x 60.5 cm; Florence, Palazzo Pitti, Galleria Palatina) |

The maiden’s left arm is encircled by a narrow blue and gold bracelet bearing the inscription Raphael Urbinas, the artist’s signature and love bond. In the background can be seen a myrtle bush and a quince branch, symbols of fertility and love and symbols of the goddess Venus. The portrait is imbued with carnality and suspension, earthly reality and elusive character, superiority and condescension by means of a gentle but precise and solid plastic, caressing in the harmonious resonance of the warm chromatic values: this is how the art historian Nello Ponente had defined it.

Aleardo Aleardi in his writing describes Raphael as a young man with a regular face, delicate features, brown hair, which he loved to wear very long, brown though locchio full of suave benignity; long neck and slender; olive-colored. A tall person, his bearing exhaled elegant grace; his manners native courtesy. We see this in theAuthoritratto that lurbinate made roughly between 1504 and 1506, preserved in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. Lartista appears half-length, in profile, dressed in black with a hat of the same color. His skin is olive, his face has a regular shape, with fine, graceful features, and he has dark eyes, as dark as his almost shoulder-length hair.

The history of art, especially in the nineteenth century during the periods of Romanticism and Neoclassicism, has traveled by fantasy imagining the love story between Raphael and the Fornarina, the two young lovers. This is a fascinating love story that nevertheless oscillates between reality and legend: the protagonists actually lived and it is true that the Fornarina was Raphael’s muse in some of his paintings, but there is no tangible proof that a tender feeling blossomed between the two young people. Romantic souls, like the writer, nevertheless wish to believe in the veracity of this love.

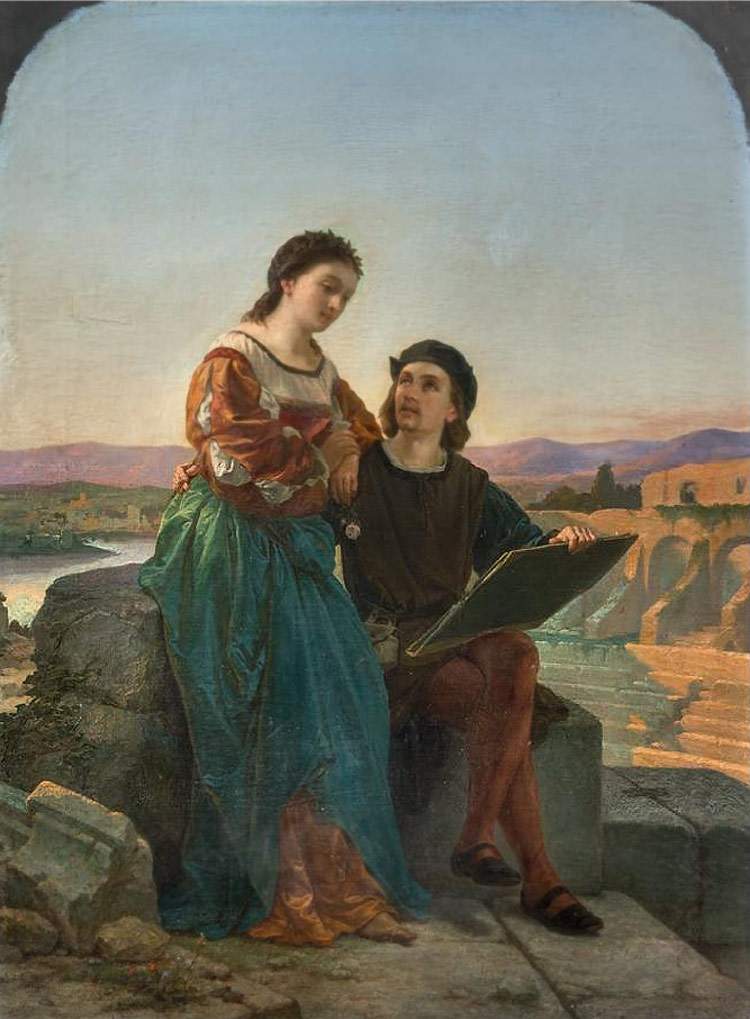

Several were the works that painters and sculptors devoted to this theme. Milanese artist Federico Faruffini completed his painting between 1857 and 1858: in the foreground, in the center of the scene, the two young people are placed next to each other, sitting on a rock. Raphael holds a canvas in his hands as he turns his gaze toward the Fornarina, who in turn stares at the canvas. A landscape with ancient ruins can be perceived in the background, and at the edges of the painting an arched shape can be glimpsed that almost frames the scene. It is a painting that highlights the color choices, particularly in the girl’s dress and the rather idyllic landscape.

And again the painting by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres made in 1814 and exhibited at the Fogg Art Museum in Cambridge, Massachusetts: the scene takes place in an interior, presumably in the painter’s studio. The two young people are seated and embraced in the center of the work; he turns his gaze back toward the painting on the easel, she toward the viewer. Renaissance elements are also noticeable, such as the clothes of the respective characters (she wears the same gold and blue turban as the Fornarina of Palazzo Barberini) and the landscape that can be glimpsed through the window with the displaced curtain and the colonnade on the left of the scene. In the studio depicted in the painting there is in semi-darkness, almost hidden by the canvas on the easel, a famous work by the artist: the Madonna della Seggiola, which Raphael completed between 1513 and 1514 preserved in the Galleria Palatina in Florence. For Ingres, Raphael’s Fornarina was larchetipo della bellezza muliebre.

Pasquale Romanelli also, in the 1860s, depicted Raphael and the Fornarina in one of his works, this time in sculpture, now preserved at theHermitage in St. Petersburg: this is the first meeting between the two, during which the artist tries to convince the beautiful girl to pose for him. He encircles her by gently laying a hand on her shoulder and looks tenderly at her; she stops him by placing her hand on the young man’s leg. The Fornarina appears with an uncovered breast, a detail that recalls the Fornarina of Palazzo Barberini, and is a sign of modesty and danimo loyalty, despite what one might think. The figure of Raphael is also elaborated with theAutoritratto preserved in the Uffizi Gallery in mind. The sculptural group is of extraordinary finesse in the decorations of the robes, expressions, and detailed detail and is the result of the sculptor’s sympathy for Romanticism. And again, the works of Giuseppe Sogni, Cesare Mussini, Francesco Valaperta, Francesco Gandolfi, and Felice Schiavoni, all the way to the twentieth century with the desecrating works of Pablo Picasso and to the present day with the photography of Joel-Peter Witkin: long is the list of artists who have been inspired by the story of Raphael and the Fornarina.

|

| Federico Faruffini, Raphael and the Fornarina (1857-1858; oil on canvas, 83 x 62 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Raphael and the Fornarina (1814; oil on canvas, 64.77 x 53.34 cm; Cambridge, Massachusetts, Fogg Art Museum) |

|

| Pasquale Romanelli, Raphael and the Fornarina (c. 1860-1870; marble, height 97 cm; St. Petersburg, Hermitage) |

|

| Giuseppe Sogni, Raphael and the Fornarina (before 1826; oil on canvas, 169 x 125.5 cm; Milan, Accademia di Brera) |

|

| Cesare Mussini, Raffaello e la Fornarina (1837; oil on canvas, 184.5 x 248 cm; Milan, Brera Academy of Fine Arts) |

|

| Francesco Valaperta, Raffaello e la Fornarina (post-1850-ante 1866; oil on canvas, 91.5 x 128 cm; Varese, Civico Museo d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea) |

|

| Francesco Gandolfi, Raffaello e la Fornarina (1854; oil on canvas, 100 x 100 cm; Milan, Accademia di Brera) |

|

| Felice Schiavoni, Raffaello e la Fornarina (c. 1850; oil on panel, 52.8 x 69.8 cm; Brescia, Musei Civici d’Arte e Storia di Santa Giulia) |

|

| Joel Peter Witkin, Raphael and the Fornarina (2003; gelatin silver salt print applied to cardboard, 87.6 x 67.3 cm) |

Lamore between the famous painter from Urbino and the beautiful maiden daughter of a baker has repeatedly been a source of inspiration for writers and artists, and it is through the latter that their love will never end, for it will be remembered in art and literature for leternity.

Reference bibliography

- Sergej Androsov, Massimo Bertozzi, Ettore Spalletti, After Canova. Paths of Sculpture in Florence and Rome, exhibition catalog (Carrara, Palazzo Cucchiari, July 8-October 22, 2017), Fondazione Giorgio Conti, 2017

- Anna Finocchi (ed.), Faruffini. Storia di una collezione, exhibition catalog (Milan, Gallerie Maspes, May 13 to June 26, 2016), Gallerie Maspes, 2016

- Lorenza Mochi Onori, Rossella Vodret (eds.), Galleria Nazionale dArte Antica-Palazzo Barberini. Paintings. Systematic catalog, L’Erma di Bretschneider, 2008

- Giuseppe Sgarzini, Raffaello, ATS Italia, 2006

- Marco Fabio Apolloni, Ingres, Giunti, 1994

- Nello Ponente, Raphael, Skira, 1990

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.