A lesson from Roberto Longhi. Attilio Bertolucci talks about the art historian in private

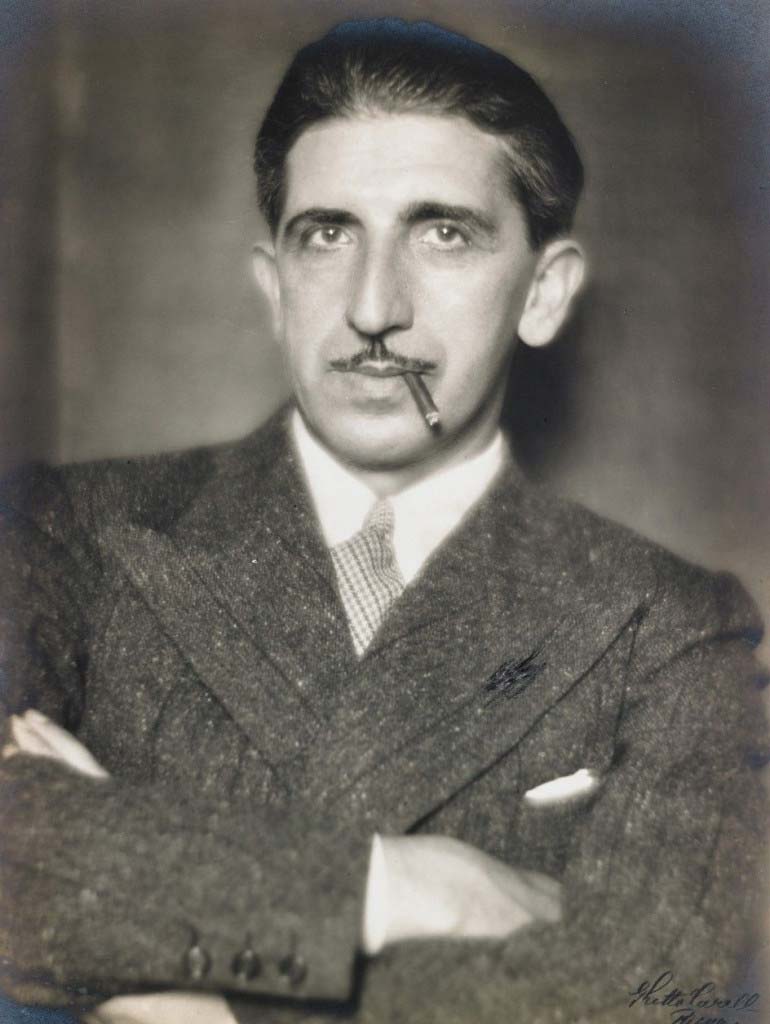

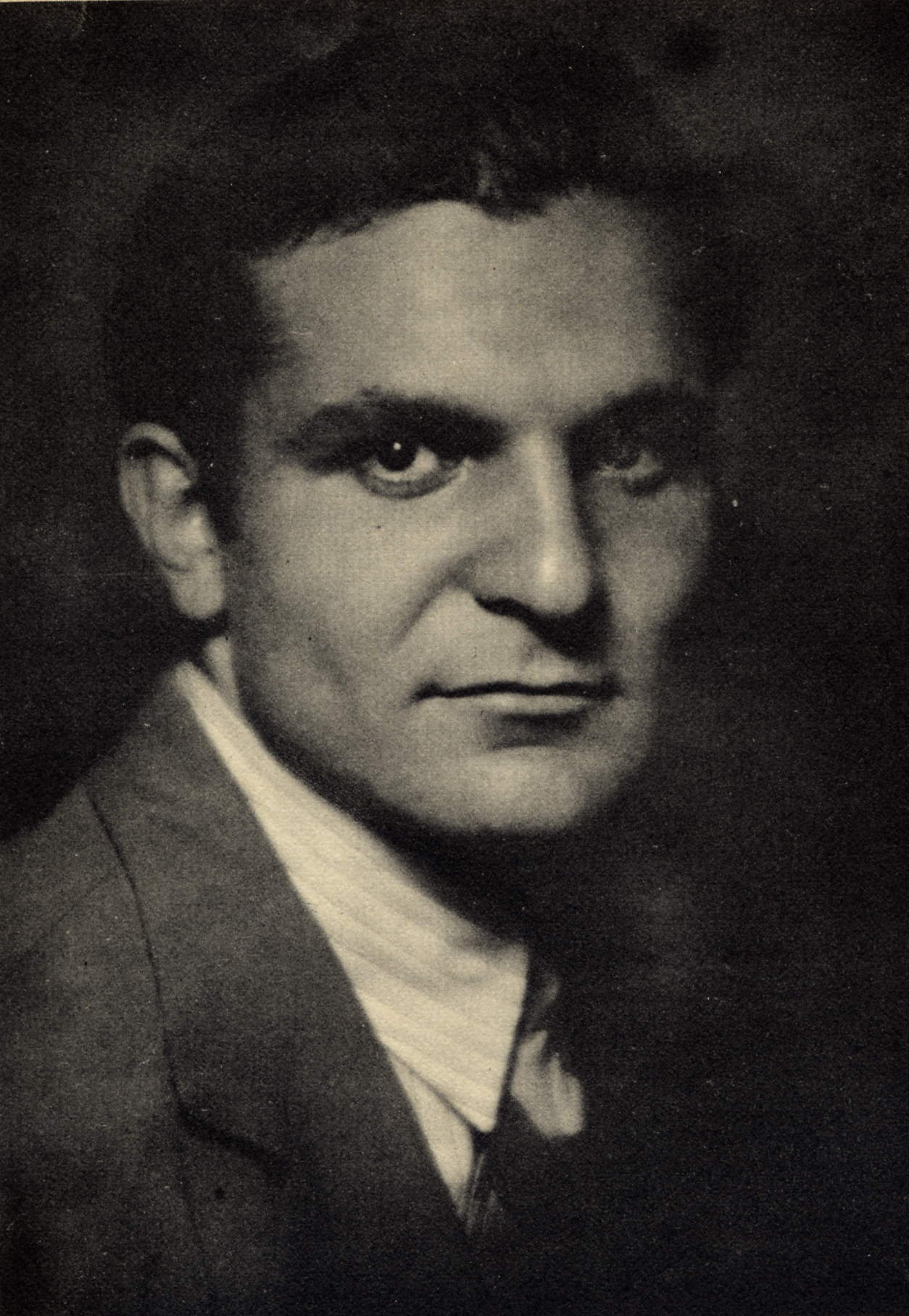

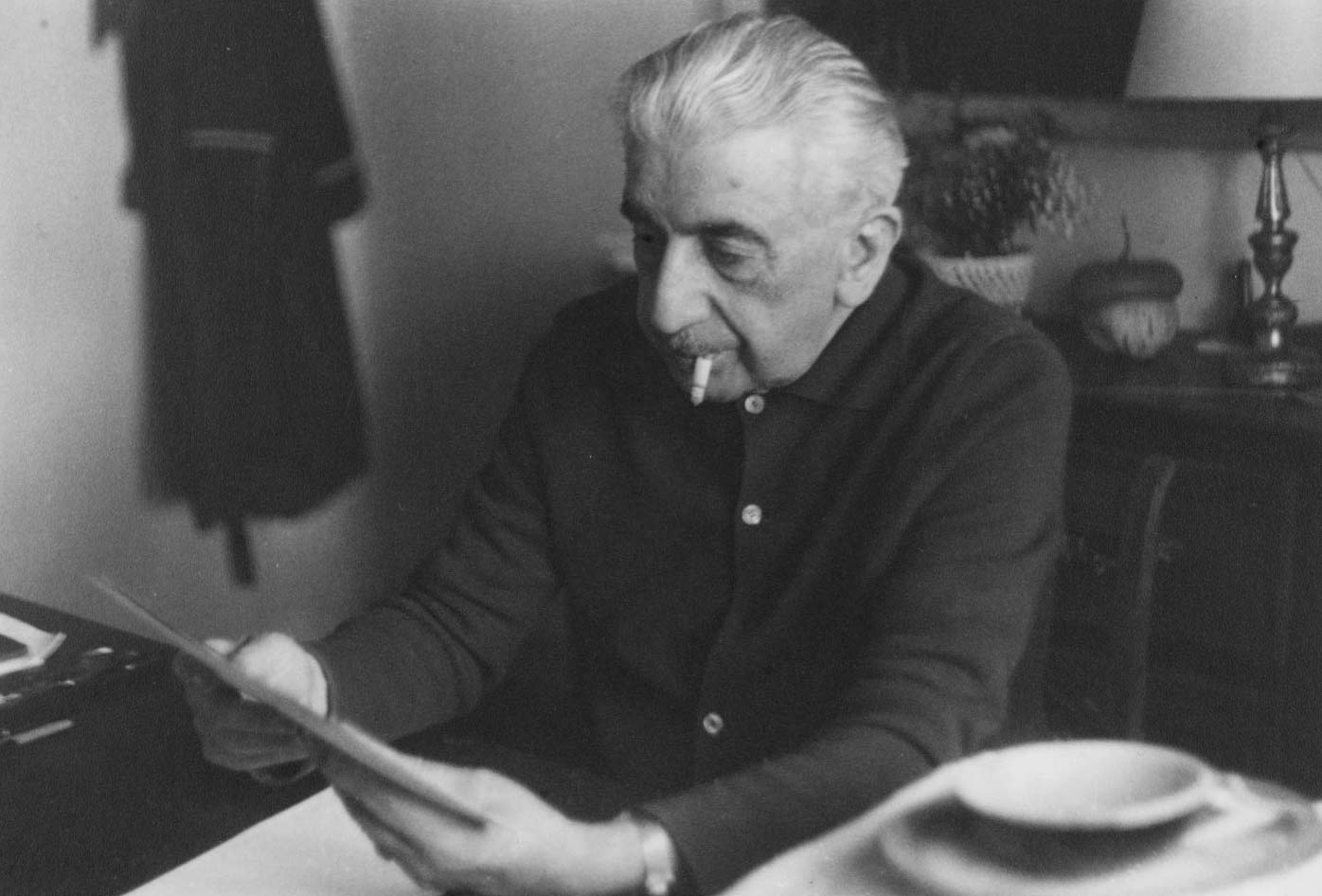

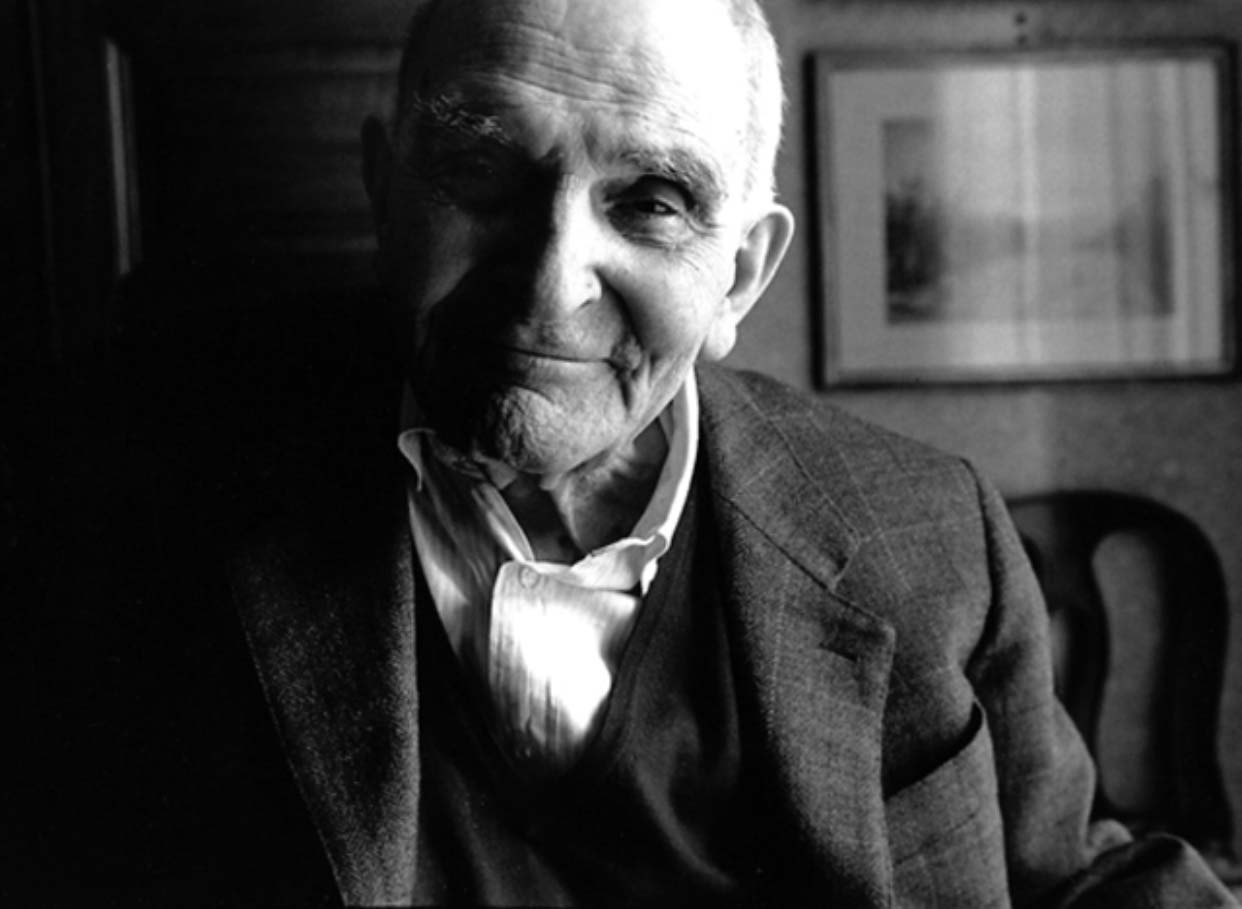

Attilio Bertolucci (San Prospero Parmense, 1911 - Rome, 2000) is one of the greatest Italian poets and also one of the most reliable witnesses of the culture of our twentieth century. But he is so without conceit and declares the masters to whom he owes much: perhaps most of all, Roberto Longhi (Alba, 1890 - Florence, 1970), whose student he was from 1935, when Longhi took over the chair of art history at the University of Bologna. I met Bertolucci in Tellaro, near the small port of Lerici, in his beautiful and bizarre octagonal house like the Baptistery of Parma, his town. In a singsong voice, full of Parma’s erre and timelessly light tone, he tells me about his youth with Longhi, along with Giorgio Bassani, Alberto Graziani, Francesco Arcangeli and others. And he tells me about his lifelong friendship with Roberto Longhi, their familiarity and the attention the art historian paid to the Bertolucci boys: to Bernardo, to whom he gave his first camera, and to Giuseppe, whose curious informal paintings he admired. Article originally published in the November 1990 “Giornale dell’Arte.”

BZ. When did you first meet Longhi?

AB. More than met, I would say saw. It was in 1934, in Parma, on the occasion of the Correggio exhibition. At a conference at the university, in the beautiful 17th-century hall “dei Cavalieri,” he was presenting for the first time as a work by Correggio the Portrait of a Lady from the Hermitage, which until then had been wrongly attributed to Lotto. I then saw him again the following year in Bologna, where Stravinski was conducting a concert in which his son played the piano. It had given me a thrill to see this tiny little man, identical to the caricature Picasso had made of him, Sitting in the audience, there was also Longhi with Anna Banti. Never, however, would I have thought that in that same autumn he would take the chair of art history in Bologna. By the way, there had been in 1933 the exhibition of Ferrara painting of the Renaissance el the following year the masterpiece that is Officina ferrarese had come out, which I had immediately read.

At that time was your interest in Longhi only literary?

It certainly began as literary. But reading on Piero della Francesca definitions like that of Christ in the Resurrection of San Sepolcro, “hideously sylvan and almost bovine,” or the pages on Cosmé Tura or Ercole de’ Roberti inOfficina ferrarese, I was discovering something absolutely new. And from those extraordinary texts, it was inevitable that I would approach, albeit by a circuitous route, the history of art. In any case, having learned from Ninetta, then my fiancée, who was attending Literature in Bologna, of Longhi’s arrival at that university, I immediately left Law School in Parma to go and study with him. And he began with the famous prologue on Bolognese painting, “From Vitale to Morandi,” a Longhian title par excellence, which reminds me of another, perhaps also beautiful, but written “for Longhi” and not “by Longhi.”

Which one?

The one From Cimabue to Morandi, for the Mondadori volume of the Meridiani series with an anthology of Longhi’s writings, which came out very few years after his death in 1970. That title is meant to celebrate “the bones of Roberto Longhi” as those of a scholar and not as what they are: of an extraordinary writer, who is first and foremost the greatest Italian art historian of the century. Many inconsistencies with Longhi’s thinking appear. First, he did not like to be considered a “fine literary scholar.” Then he was the first not to believe in a single, progressive history of Italian art, as the reduction in a single volume of his writings might suggest. Then again the oddity, within a historical trend arrangement of the different essays, of finding last in the volume the writings on modern art, which are actually the first, by Longhi as a very young man. To end with the absence from the volume of any photographic reproduction of the artworks commented on. Tell me, using the example of a painter who is very dear to me, Amico Aspertini, how can one, without the image of the Pala del tirocinio in front of one’s eyes, read (and understand) what is said in theOfficina ferrarese about the very small details at the bottom of this painting in the Bologna picture gallery: “In the country, what events! The procession of the Magi, having sighted the throne of the Virgin from the heights of Battivento, pauses to hollow out from their baggage the donations that will have to be exhibited shortly; further on come certain cheerful cardinals on mounts that seem still drawn from the stables of the trecentista Vitale; and, behind, pages and armigers go traipsing along, more witty than in an Altdorfer. On the hillock in tally, at the announcement of the mystic event, some shepherds improvise a saltarello that no one else in Italy, not even Filippino, would have been able to paint more diabolical; a quicksilver that already makes one think of Callot’s pezzenti and even of the pungent fantasies of our Scipio.”

Who were his fellow students at the university?

There were very few of us. A few girls, a few priests, then Francesco Arcangeli, Giorgio Bassani, Alberto Graziani, Augusto Frassineti, Franco Giovanelli, Antonio Rinaldi. In short, there were six or seven of us, all in some way already called to a strong interest in literature and art. Longhi, for his part, gave us a great deal. In the three years we were together he showed himself to be of absolute generosity. He didn’t miss a lesson and even when he took us out on the practice day, he was with us the whole time. And the things I had already seen on my own, maybe even just an hour before, seemed completely different. They came alive in the magic of those words that were, on his lips, like living things. After all, Longhi really did look like a bit of a magician. Very elegant, always wearing very strange lizard shoes on his feet and with that somewhat Middle Eastern face: with a big nose, a thin mustache and a Turmac cigarette hanging eternally from his lips, driving around Bologna in an American car that Banti drove slowly.

What is the story of a “Turkish Longhi”?

This is an affair from many years later, around 1960. At a lunch in Forte dei Marmi with then Minister of Education Medici, Longhi said that his family came from the same areas where the minister was born. That is, from Concordia, a town near the Po River in the province of Modena. Medici responded by telling how Concordia was a place where many Turks had taken refuge at the time of the Venetian Republic, coming up the Po from the Adriatic. Immediately, but I said nothing at the time, a story by Banti came to mind. An orphan girl who was staying in a Venetian boarding school and during the Sunday outing, standing in line with her classmates, she began to be followed by a Turk who stared at her fixedly. Such was the power of that gaze, that after a while Lavinia, that was the girl’s name, escaped from the boarding school with the same Turk. I do not know whether the tale is pure fantasy. What is certain is that even today the coincidence between Banti, Lavinia, Longhi and the Turks at Concordia continues to seem very peculiar to me.

How did the classes take place?

First of all, they were held very early in the morning. He was concerned about the fact that until not many years before, Bolognese ladies would go in droves at tea time to the art history lectures given at the university by Enrico Panzacchi, a man of letters who was a friend of Carducci. And he did not want ladies to come to his lectures. So he had chosen eight o’clock in the morning as his time. So that to be on time, I had to leave Parma very early. One time there was a big snowfall, and when I entered the classroom I still had some snow on my coat. Maybe the same one, Longhi told me as he looked at me, that had ended up on Solomon and the Queen of Sheba from my baptistery. Then, when he would start talking, always holding a cane to point out the details of the pictures he projected into the darkness of the long narrow classroom where the lecture was given, he would begin a firework of inventions of all kinds. From his speaking in such bold and fascinating linguistic metaphors, to the voices he gave to the artists, making them speak in the dialects of the areas from which they came, to give greater incisiveness to their belonging to local schools; a theme to which he attached great importance. Then the taste for jokes. For example, of Benvenuto Supino, his predecessor in the Bologna chair, he would often tell us that it was perhaps better if he had called himself “Shabby Bocconi.” Or, after the other students had left the lecture hall, he would go off on us faithful to the Duce, declaiming in a bombastic voice about our “eight million bicycles,” not “of bayonets.” Here, Longhi was someone who for the pleasure of a sharp phrase was willing to lose his university professorship.

Did you have any chance for a critical dialogue with him?

To my other classmates, there were not many. But to me, who was older in age than them and had already published two books of poems, one of which was reviewed by Montale, it was allowed sometimes to disagree with him. After all, all great critics make great mistakes, and Longhi made magnificent ones.

For example?

The first one that comes to mind is his critique of the Italian Ottocento, written in disagreement with his friend Emilio Cecchi, in his little book on Carrà in ’37. With that resounding beginning, in which he says that if French nineteenth-century painting is almost inaugurated with the canvas entitled Bonjour, M. Courbet, it is a pity that modern Italian painting lacks “a great painting that is finally called ’Goodnight, Mr. Fattori.’” Not to mention Segantini’s “mystical buzzard, perched on the trichromatic rezzo of Engandine litter,” or de Chirico’s “orthopedic god,” But then certain paradoxical judgments of the Venetian Viatico, such as the supposed superiorities of Iacopo Bassano over Tintoretto or Rosalba Carriera over Tiepolo. What remains extraordinary about him, however, is the absolute excellence of his critical method, which made even his negative judgments beautiful and stimulating. And I have to thank him, even at this moment, because to his exclusive credit I had an opening to art history that few other writers of my generation could have. With one danger, however: that of falling into the trap of imitating his style. For Longhi was and remains absolutely inimitable.

But what about modern art did he tell you?

He often talked about it, Apart from his well-known predilections for Courbet, Renoir and Cézanne, Boccioni, Carrà and Morandi, I remember his distrust of Picasso, whom he called “mannerist” and to whom he contrasted his (which also became mine) great love for Matisse. He would then often talk to us about Paul Klee. Cinema was also frequently discussed. Longhi was very close friends with Umberto Barbaro, whose militant anti-fascism everyone knew and who, despite this, was in Rome at the Centro sperimentale di cinematografia. It was a very close bond that lasted over time, so much so that after the war, with the help of Anna Salvatore, Longhi did the talking for him on two documentaries on Carpaccio and Caravaggio. Once, in ’36, thanks to Barbaro, Longhi had two memorable films, Dupont’s Fortunale sulla scogliera and Erich von Stroheim’s Sinfonia nuziale, brought from Rome to Bologna especially for us. The custody of the films fell to me, and since it was flammable material that it was forbidden to carry around, I had to keep it in my house for more than a month inside a large suitcase. We then screened the two films at the Cine-Guf in Parma and the one in Imola, which was directed by Alberto Graziani: perhaps the best of Longhi’s students, who if he had not died so soon would certainly have become a great art historian. Occasionally then we would also talk about jazz, a music that I had introduced Longhi to. With my 78 rpm records, I would leave Parma for Bologna and, with the usual classmates, we would go to hear them at Longhi’s house. There, often, between records, he would perform irresistible imitations. For example, he would stick, on top of his own, two big black mustaches to play Groucho Marx, when with his evil air he goes and says terrible things into the ears of strangers. There was in those meetings the same informal style of those extraordinary meeting places that were then the Cafes. Without taking the celebrated example of the “friends” in the third small room of the Aragno café, portrayed by Amerigo Bartoli (from Longhi to Bruno Barilli, Ungaretti, Cecchi, Cardarelli, Soffici and many others), I think of Parma, of the various cafés that Pietrino Bianchi frequented as the year went on, following the course of the sun, and where he would enchant us for hours talking about cinema and whatever else the guest on duty wanted to know. This extraordinary capacity for affabulation had quickly created such a reputation for him that Enzo Biagi recently told me how he and his friends had come especially from Bologna to hear him speak. A civilization this of coffeehouse meetings that our generation was the last to frequent and that is now dead forever.

About Longhi capable like no one else of grasping the grotesque aspects of reality there is a kind of legend.

He was actually a very witty man. In the winter of ’40 we went on a trip to Assisi. He was writing that beautiful essay of his on Stefano Fiorentino, of whom there are wonderful paintings in the lower church, and there Mauro Pelliccioli, with whom Longhi was a close friend, was restoring Giotto’s frescoes with the “Stories of St. Francis.” With Longhi were the still schoolboys, those like me who had remained his friends even after graduation and the “ideal” schoolboys, such as Giuliano Briganti, who was studying in Rome with Toesca. On the train to Assisi, Longhi and Briganti played one a Milanese industrialist and the other a famous art connoisseur, a certain “Porcella.” They played who made the craziest attributions, with Longhi speaking in perfect Milanese, like a dialect theater actor. There was truly laughter to die for. Also participating in that trip was Antonio Santangelo, who a few years earlier had published theInventory of Art Objects in the Province of Parma. I still remember (and I also put it in my book The Bedroom) when Santangelo, in the early 1930s, walking like an explorer, arrived at the small church in Casarola (the then unreachable village of my ancestors in the high Apennines of Parma) to file a beautiful 13th-century astylar cross. He was a very nice guy, a communist, who drank a lot of coffee.

In Assisi, did you go up on scaffolding to see Giotto’s restorations?

No, maybe it was too cold or maybe it was meeting Pietro Toesca, who was there following Pelliccioli’s work. Toesca, then, did not like his old schoolboy Longhi. So that he gave him many curt bows and forced us to leave immediately. Also keep in mind that in those years Longhi never talked to us about problems of restoration and protection. Issues that I think he addressed only in the last period of his life. As for Toesca, there was then a great rapprochement, so much so that Toesca, leaving teaching in Rome, had ideally designated Longhi himself as his successor. Even with Berenson, in his later years, Longhi made peace, after numerous, earlier problems. For example, the well-known judgment on Berenson’s Indices of ’32, which Longhi called a “new timetable of artistic railroads.” Of this rapprochement I learned directly from Berenson. Once in fact, in the mid-1950s, Gino Magnani called me to invite me to dinner at his home, where Berenson was a guest. The talk inevitably fell on Longhi, and Berenson recounted how he often visited him at the Tatti, where together they reminisced about their old masters, of whom Berenson asked him to do those imitations at which Longhi was peerless.

You, at the date of the trip to Assisi, had already graduated, but not with Longhi.

No, because in ’38 he took a sabbatical year and I could not graduate with him. I must say, however, that Longhi did not like those who graduated with him to cultivate other interests outside of art history. Just think that not even a person so deeply marked by Longhi’s teaching (nevertheless a poet) as Pierpaolo Pasolini graduated with him. Yet Pasolini, in dedicating Mamma Roma in 1962 to Longhi, said he was “indebted to him for his figurative electrocution.” For that matter, the extraordinary episode of Ricotta in the multi-handed film RoGoPag would be enough to understand what Pasolini’s relationship with lastoria of art was. Although the figurative layout of Ricotta, all played on references to Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino, owes much to Longhi but also to Giuliano Briganti’s volume La Maniera Italiana. So much so that Fabien Gérard has shown that the title of one of Pasolini’s poems from these years, “A Desperate Vitality,” comes precisely from a sentence in that book.

Right after the war you founded Paragone. Did you plan to make it a militant magazine?

No, I wouldn’t say that. Although, for the artistic section, with Longhi in the middle, it was impossible not to take sides. As for the literary section, the line we decided to follow was the one later followed by Palatina, based on the search for quality.

But did Longhi also have a role in the literary section?

His role was not to give addresses, but only as a very careful reader of the material intended for Paragone letteratura. It was he who wanted that for the first volume of Paragon Editions yes print the poems of my Indian Hut. Just as it was also he who suggested that in the second or third volume of those same editions Silvio D’Arzo’s Casa d’altri be published.

How was Paragone born?

It was in 1950. There were very few of us - Longhi, myself, Francesco Arcangeli, Piero Bigongiari and Giorgio Bassani - the day we met in Bologna to lay the foundations of the magazine. We immediately agreed on everything. Including the graphics, which we decided to entrust to Carlo Mattioli, whom I had introduced to Longhi and who, as usual, did a beautiful job. So much so that even today Paragon ’s graphics are Mattioli’s. At the end of the meeting we went to see Morandi in his studio and there I lost the opportunity to be able to buy one of his paintings at a miyissimno price. I liked one that was a definite departure from the white still lifes that, with minimal variations moon from moon, Morandi was doing at that time. It was a view of the house in front of his on Via Fondazza, with the roofs under the snow, which I later had the surprise of finding in the volume La Bologna di Morandi. “But it is not finished,” Morandi told me, “come mò to get it when it is finished.” But I did not dare; Morandi was a difficult man. Just think of how he treated poor Francesco Arcangeli, perhaps the most gifted as a writing quality of Longhi’s students, just because he had dared to write in his monograph on Morandi something that was probably true. That is, that Morandi, in addition to Piero and Cézanne, had looked at the landscape painters of nineteenth-century Bologna. Morandi discarded Arcangeli’s text (which was later published in the editions of Il Milione, as if it were, and perhaps is, a novel) and caused Ghiringhelli to entrust Lamberto Vitali with the task of drafting a new monograph. For this affair Arcangeli went through very hard times, which did not prevent him from continuing to love the great master of his city until the end.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.