All those who visit the National Roman Museum for the first time at the site of the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, just across the street from Roma Termini station, can hardly hold back their amazement when, in the halls of the paintings, towards the end of the tour they come across a splendid frescoed garden from the first century B.C., excellently preserved. These are the extraordinary frescoes of the underground hall of the Villa of Livia Drusilla, third wife of Augustus, which were once located in her Villa at Prima Porta, a neighborhood on the northern outskirts of Rome. The frescoes, although fragmentary and partly ruined (we are still talking about works from two thousand years ago), have been preserved on all four walls. They depict, seamlessly, a lush garden described with a great sense of realism: there are trees and fruit plants described in great detail, flowers, shrubs, birds fluttering and wandering among the branches and on the lawn, a fence and a marble balustrade. They inspire calm, serenity, tranquility, urging a contemplative dimension. They are one of the pinnacles of Roman painting.

Livia’s villa was discovered only in the 19th century. It is also known as “Villa ad Gallinas Albas,” that is, “to the white hens”: the legend, recounted by Suetonius, says that, after her marriage to Augustus, Livia saw an eagle pass through Veio that laid a hen in her lap bearing a laurel sprig in its beak: Livia interpreted this as a good omen, and decided to raise the bird, giving birth to chicks. There had been no shortage of scholars of antiquity in previous centuries who, finding mention of the villa in written sources, wondered about their location, which was, however, only precisely identified in 1828, near the Prima Porta crossroads. The first excavation, however, dates back to 1863, when the owner of the land under which the villa was located, Count Francesco Senni, ordered some excavations “to trace objects of Antiquity in the Prima Porta Estate called ad Gallinas outside Porta Flaminia about 8 miles distant from Rome,” as stated in a note preserved in the State Archives of Rome. The work bore the hoped-for fruits: from the excavations emerged statues (including the very famous Augustus of Prima Porta now in the Vatican Museums), architectural fragments, glass, and various objects. In the spring the frescoes now preserved in the Museo Nazionale Romano were discovered: “On April 30, 1863,” one reads in the excavation reports, “a Stairway was discovered towards the East in the vicinity of the substructures of the boundary walls of d.ta Villa leading for now to no. 2 Rooms, one of which has walls of white color, with a floor of white and black Mosaic of ordinary construction, and a Room to the Left of the stairs with walls painted in good condition representing fruit trees, and flowers, with various Augelli, the vault entirely ruined, and the stuccoes that surrounded it are found among the rubble with which said room is filled.”

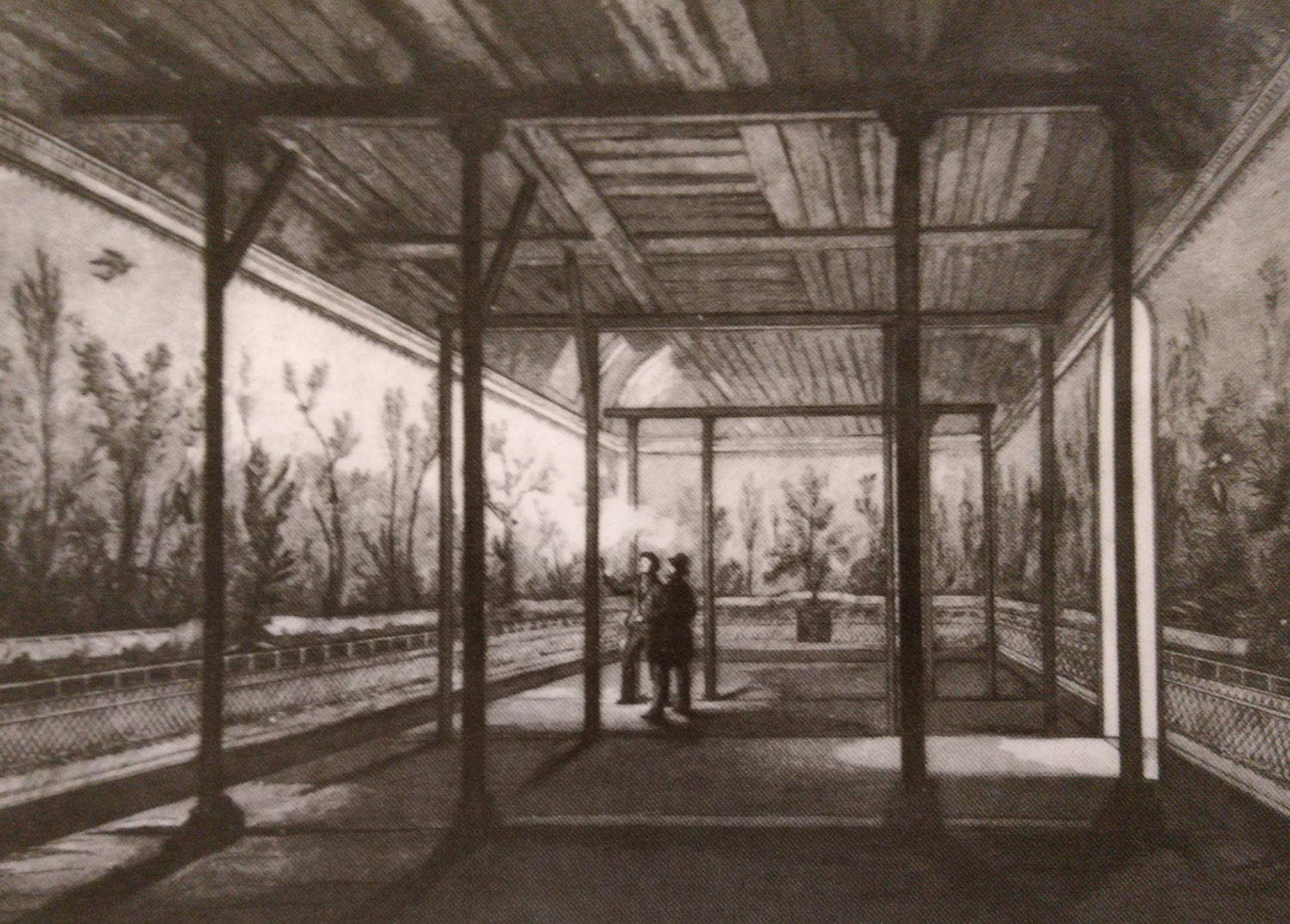

The first to describe the frescoes in detail was the German archaeologist Heinrich Braun, in a report published in the Bulletin of the Institute of Archaeological Correspondence (May-June 1963): “the paintings, or rather a single and continuous painting, run around all four walls representing a garden; it must be imagined that the room itself forms almost a square in the midst of a dense plantation, which at no point allows a free view of the open countryside [...]. They are all garden trees, some bearing fruit, such as apples and pomegranates, others serving rather for ornament and showing, how even the taste of the ancients studied to bring together in their villas the vegetation of different areas, planting next to the palms of the south various species of firs and other trees of the north. Nor are there any lack of inhabitants to this forest: they are varied birds that sing, peck at fruits, feed their broods and otherwise amuse themselves. Of human beings at the meeting there is not a single one present: nevertheless the artist has been able to indicate with fine judgment, that we are not in a site perhaps once inhabited and now abandoned: that indeed a beautiful round wire cage, as they are used even in our days, with a goldfinch inside, makes us suppose at once, that there must be men living nearby, neither these uncouth but cultured.” Initially, the frescoes were left in place so as not to further compromise their state of preservation: over the years there were thus several attempts at restoration, which, however, failed in their objective of allowing the frescoes to remain in place. This led to 1951, when theCentral Institute for Restoration decided to tear out the frescoes, to carry out a new integral restoration and to transfer them first to the Museum of the Baths of Diocletian and then, since 1998, to the National Roman Museum in the premises of Palazzo Massimo, where they are still located today.

The frescoes, dated between 30 and 20 B.C., are among the best-preserved examples of Roman wall paintings, as well as among the most intact. They decorated a basement room, which received light from a small skylight carved into one of the lunettes above the short walls (the room was covered by a barrel vault): curiously, the frescoes were preserved so well despite their underground location due to the fact that the painter painted them on a plaster applied over tiles that were actually detached from the wall and thus remained protected thanks to a cavity, reasoning that moisture did not affect them. We do not know for sure what the use of the room was: it was probably a triclinium, or dining room. Definitely a room where the inhabitants of life went for recreation, especially in summer, given the coolness that the room could provide. The decoration of the room, wrote archaeologist Salvatore Settis, “forms with the hypogeal character of the room a strident, intentional contrast. The entire available surface below the vaulted ceiling is decorated with an airy, uninterrupted, life-size garden painting, which not even at the corners is interrupted, but rather continues, with a great variety of trees, plants and birds. No architectural elements (not pillars, not columns) punctuate the composition vertically; but the artifice of perspective that organizes the walls in skillful ’garden architecture’ is articulated on a double fence that runs all around.” As mentioned above, although there are no architectural elements, we are nevertheless in the presence of an environment modified by human beings: the garden space is in fact delimited by the double fence, which has the narrative purpose of suggesting the extent of the garden and the technical purpose of providing the visitor to the room with his or her own point of view. It is also interesting to note that the painter, who is unknown, used an ingenious device (which would later be typical of Renaissance painting) to suggest depth: the elements in the foreground appear very detailed, while those in the background are more blurred.

The sky above the garden is clear, there are no clouds, it opens up to infinity, and the painter’s descriptive meticulousness is such that within the painted garden of Livia’s villa as many as twenty-three tree species have been recognized, all typical of Mediterranean environments except for two (the date palm, characteristic of warmer climates, and the Norway spruce, which instead comes from the north) and sixty-nine avian species, a circumstance that, Settis explained, makes the garden “as artificial as ever,” not least because of the fact that blooms are observed there at the same time that, in reality, are appreciated in different seasons. Scholar Giulia Caneva provided the complete list of plants that can be recognized in Livia’s garden: commonscolopendrium (phyllitis scolopendrium), spruce(picea abies), stone pine(pinus pinea), common cypress(cupressus sempervirens), holm oak(quercus ilex), oak (quercus robur), bay laurel(laurus nobilis), poppy(papaver somniferum), rose(rosa centifolia), quince(cydonia oblonga), boxwood(buxus sempervirens), wild violet(viola reichenbachiana),myrtle (myrtus communis), pomegranate(punica granatum), ivy(hedera helix), strawberry tree(arbutus unedo), oleander(nerium oleander),acanthus (acanthus mollis),viburnum (viburnum tinus),chrysanthemum (chrysanthemum coronarium), fetid chamomile(anthemis cotula,iris (iris), and date palm(phoenix dactylifera). Birds include doves, sparrows, blackbirds, robins, goldfinches. It is certain that Livia’s viridarium is not a true portrait of a garden, but rather, if anything, a kind of “botanical catalog,” to borrow an expression from Settis. One will notice a certain prevalence oflaurel, which could be read in a symbolic key, in relation to the myth of the white hen that would lead to the very construction of the villa: according to Suetonius’ account, in fact, there was a laurel grove in the villa where branches destined for emperors and triumphants were gathered, who had the custom of planting a new tree after a triumph.

As for the constructive elements of the environment, “extension of space, negation of the wall, more or less skillful and graduated perspective construction,” writes Settis again, “are constructed to capture the gaze of the observer, to transport it from the perception of the whole to the observation of the detail. It is an agreed-upon illusion, which does not pretend so much to deceive as to impose the rules of a game, based above all on the effect of estrangement that the ’garden-like’ decoration of a closed room produces on the observer, all the more so if it is underground.” The decoration intends in particular to insist on two points: on the one hand, theart of gardens(ars topiaria), which was particularly appreciated by theRoman aristocracy, and on the other hand, thepainter’s skill in proposing to the onlooker an illusionistic garden that, through breaking through the wall, denies the architecture that contains it. A way to surprise visitors, a desire to have a room where it was possible to admire the product of one of the greatest passions of the Roman nobility, a setting to relax while observing a lush garden. Many could be the purposes of such a representation. Nonetheless, many scholars have wondered about the possible symbolic meaning of the Livia garden frescoes, beyond the purely decorative aspects. Is it therefore possible that these paintings could also be interpreted on an allegorical level?

The problem is complicated by the fact that we have very few examples of decorations similar to those in Livia’s garden. And even in the literature the sources are scarce: Settis advances only one example, that of Pliny the Younger, who describes a room in his villa, a cubiculum, shrouded in greenery and dominated by a plane tree that stands near it, and with its plinth covered with mamo; nor is the painting less graceful than marble, showing foliage populated with birds. No help, however, on the possible meaning. The Calabrian scholar noted that garden decorations, in Roman antiquity, are found in only two contexts: rooms of villas such as Livia’s, and tombs. In the latter case, the decoration with plants and shrubs would ideally refer to the funerary gardens that often surrounded tombs, while in the case of residential decorations they would simply refer, writes Settis, to “current forms of expression of social prestige in the structure and decoration of the house, as it is, precisely, the garden.” A garden, then, as an ostentation of social prestige. Others, such as Giulia Caneva herself, have instead dwelt on the symbolic meanings of plants, speculating that Livia’s garden may have had a spiritual or religious connotation. It is quite unlikely, the scholar has written, “that in a place of such value and significance nature would be represented as a mere description of an idyllic and fertile landscape, or as an ornament that satisfies a purely aesthetic pleasure. The timely and orderly cadence of trees, plants and birds undoubtedly contains a key that could be not only corollary to the reading, but indispensable and fundamental support.”

Many elements would suggest a symbolic function of the plants: the fact that there are repetitive elements, the presence of mostly native plants, the seasonal inconsistencies, the arrangement of plants that often presents juxtapositions and geometries, the lack of the human element, and the presence of an abundance of birds of different species that are difficult to find in nature all together. The background, Caneva notes, consists of plants linked to funerary meanings: the cypress, oleander, holm oak, boxwood. These are contrasted instead with trees that refer to life, such as the palm, laurel, arbutus, and viburnum, following repeating patterns. Flowers (the rose, chrysanthemum, chamomile and poppy) also have meanings connected to funerary ritual. Birds, in turn, could be representations of the soul or spiritual states of being, and their flight the connection between heaven and earth. In summary, Caneva writes, “it is reasonable to think that this is therefore a representation of an ideal garden in which the spiritual and religious element clearly dominates, leading to the vision of human life as transitory, but eternally capable of renewal and regeneration, as in the cosmic cycle of nature. It would transpire a worldview in which death is not funereal, but only a moment of passage awaiting a new birth, and a reference with the mystical Heracles, a symbol of the struggle sustained by man to achieve the spiritualization that will assure him immortality, also seems clear.” Another theory has it, however, that the lush garden represents the prosperity achieved by Rome under the Pax Augustea.

Today the Villa of Livia at Prima Porta, although devoid of its frescoes (which, as mentioned, can be admired at the National Roman Museum: faithful reproductions have been arranged in the underground room), is an archaeological site that can be visited, open to the public according to a pre-established calendar whose dates are decided by the Special Superintendence of Rome and published on its website. In order to open it to the public, a long and complex work of recovery and restoration of the rooms, mosaics and wall paintings was necessary, as well as an enhancement intervention to allow the public to better know this extraordinary place. It is one of the most important Roman villas of its period: to enter it, to visit the rooms where the emperor’s and Livia’s chambers were located, the courtyards, the elegant reception rooms, is to get an idea of how the Roman aristocracy must have lived at the time.

The villa was one of Augustus’s most beloved residences: it was a complex that, wrote the scholar Gaetano Messineo, “stood out, and could for this reason arouse in the young Livia a feeling of nostalgia, because of its particular position which, although not characterized by altitude or rugged morphology, offered a very wide, soothing view of the Tiber valley, enclosed by a distant backdrop of mountains.” A setting of rare scenic beauty, a sumptuous villa, lush woods, a garden rich in essences, later reproduced in the triclinium. Today, we can only get an idea of what that magnificent complex must have looked like. But the paintings that have survived represent one of the most interesting and incredible survivals of ancient Rome.

Reference bibliography

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.