In the space of a very few years (1518 to 1522) it fell to Antonio Allegri of Correggio to become the painter-interpreter, and brilliant transfigurator, of the admirable ideals springing from the minds of the three greatest women of the Northern Renaissance. Of them we give here a ràpido mirror and reasons. Abbess Giovanna Baroni of Piacenza, in 1518-19: with the astonishing fresco in the Camera di San Paolo in Parma that remains to this day the source of an extraordinary and almost inexhaustible cultural symbiosis. Countess Veronica Gàmbara, Lady of Correggio, host to kings of France, Emperor Charles V, poets and men of letters of high renown: with the exceptional polysemous portrait (1520-1521) that now stands in the Hermitage in St. Petersburg. The Marchioness of Mantua Isabella d’Este Gonzaga, intellectual ruler of the Italian courts through her patronage, collecting, and her own elaborate self-celebration: with the two splendid Allegories (1522) that happily concluded the new home of her lyrical and princely Studiolo.

Correggio,

Correggio,

We commemorate here the fifth centenary of an event that might seem minor but offers to the anthology of Renaissance wonders a double gem incomparable in beauty and intellectual significance. This is a contribution of the Friends of Correggio Association, which stands alongside other exegesis.

A somewhat narrative premise is needed in order to bind the certain historical data with the hypothetical connective that can make a real, dense and enveloping story complete. Isabella d’Este Gonzaga, Lady (and not by mere title) of the Mantuan State, found herself around the year 1520 with the rather considerable age of 46 years tried by numerous pregnancies, travels and the recent long pilgrimage to Sainte-Baume near Marseille (1517) to venerate in person the grotto and the memory of Saint Mary Magdalene. The death of her husband, Marquis Francesco II Gonzaga (1519), made her directly invested in the affairs of state, and in addition, the complex artistic construction site for the renovation of the old part of the Palace engaged her in person on a daily basis. For all this, she decided to move her Studiolo and the “Grotto of Antiquities” from the uncomfortable rooms of the old castle of San Giorgio to the more pleasant place of the Corte Vecchia on the first floor, in the heart of the marquis’ representation. The Studiolo had become famous for the presence of paintings by Mantegna(Il Parnaso eppoi Il Trionfo della Virtù e la cacciata dei vizi); by Perugino(La Lotta tra Amore e Castità); and by Lorenzo Costa(Isabella d’Este incoronata nel mondo di Armonia and finally Il Regno del Dio Como). Already these titles outline for us the extended theme of the struggle between good and evil, between wisdom and carnality, without wanting to hide a winning personal protagonism of Isabella herself. The sources for the princely patron’s multiple and complicated lucubrations were drawn from an extensive literature in ethical terms and with chosen mythographic roots, but translated into exaggerated particularisms, demanded and poured out on the succubus painters. Let us not forget that in the new arrangement the passage between the Grotto and the Studiolo was adorned by two portals of which Gian Cristoforo Romano’s, beautiful and still in situ today (c. 1501), also appears to be paginated by the same motifs. The open tree-lined courtyard then bore a tall epigraph, spinning on the walls, where Isabella declared herself “niece of the Kings of Aragon, daughter and sister of the Dukes of Ferrara, wife and mother of the Marquises of Mantua.” What we might call the “new identity room” received an honorary majolica tile floor and a magnificent gilded wooden ceiling. The paintings we have listed were arranged on the long sides of the room, but the new exit wall left two vertical spaces at the sides of the door; from them came Isabella’s thought for a paradigmatic conclusion to the long theme. Indeed, the noble Estense had made herself a banner (verdially “triumphal and pious”) of every virtue: whose ringing dianas composed upon herself the feminine ideal of the Renaissance. Wisdom was to be celebrated and Vice relegated to humiliating failure.

Our narrative now aims to follow the Lady’s quest to complete the figurative decor of the Studiolo: to choose a painter who would work with larger figures than the constrained ones in the previous series and who could powerfully and gracefully imprint both the final admonition of the insistent ethical preaching of the walls and the solemn celebration of the noble patron as the moral instructor of an entire society. Isabella thought of Correggio. For many months she had been receiving admiring praise for the works of that distant pupil of Mantegna whom she had known as a young fresco painter at the Master’s Chapel (and who had then sent her that “Cristo giovenetto di anni circa duodeci” never painted for her by Leonardo) and now brought to Parma. Certainly the glittering Camera that Antonio had frescoed for the abbess of St. Paul’s with an admirable mythological and biblical interweaving had intrigued her, and how! Then the dome of St. John the Evangelist had elicited unparalleled choruses of incense. Now, in the winter between 1520 and 15121, the Countess of Correggio, her friend Veronica, announced to her that “the grand master of art” had begun for her a magnificent, solemn, and dense portrait: a real treat for the eyes and the soul. The Marquise Gonzaga lost no time: she sent a cavalryman, as was her wont, and asked for a meeting with the painter. Thus in the incipient spring of 1521 the thirty-year-old Allegri, animated by his recent marriage and full of enthusiasm for the progress of his career, resumed from his native place the well-known path to the Polirone: he saw again the monks of his 1513 undertaking, from them he had again the friendly ferry from the Gorgo on the great river, andppoi he looked out over the lakes of the Mincio catching sight of the towers of San Giorgio. During the two or three days of her stay in Mantua here, in the Corte, one of the most intense and fascinating conversations of art that history could recall took place: Isabella and Correggio dueled over culture in search of the final Allegories for the Studiolo cycle. The Estense put on the table all her semantic, allusive capacity, radiated in the innumerable details of the proposed plot; and Correggio (who certainly did not reject the scheme) implanted in contrast his prodigious, comprehensive and brilliant synthesis, albeit all entrusted to a few substantial figures.

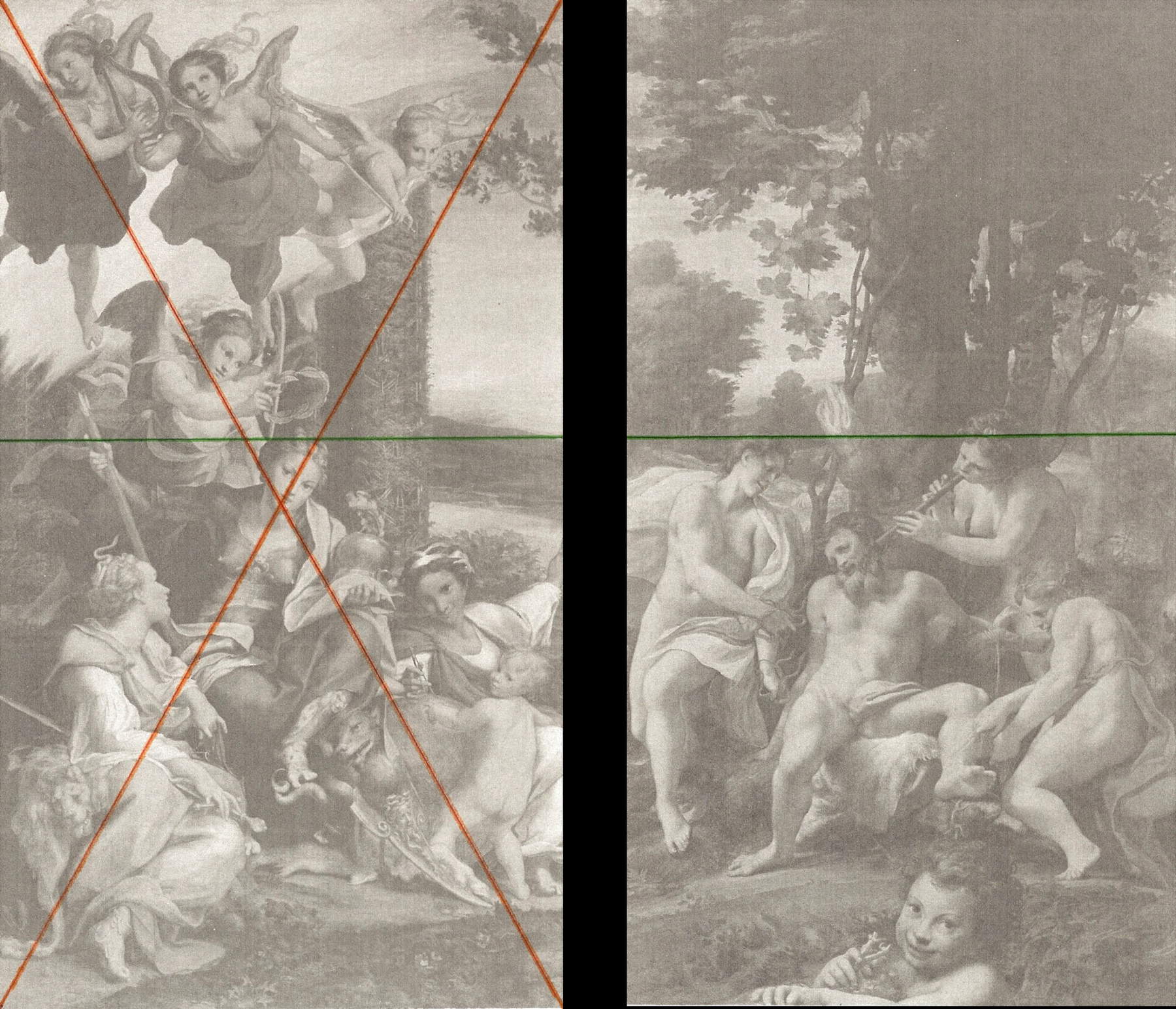

We have no commissioning contract, but the document carefully taken up by the very accurate Elisabetta Fadda records a 1522 payment to Correggio from the court of Mantua, that is, from Isabella. In an inventory then of 1542 regarding art objects owned by the marquise, the two paintings by Antonio da Correggio “at the sides of the door ne la intrata” are recorded. So no objective doubts, neither historical nor critical. In the same inventory the “historia di Apollo et Marsia” is called first, but equivocating on the subject, rather than theAllegoria del Vizio or dell’Insipienza. This one, as is commonly thought, was intended to conclude with a cautionary passage the left wall by exiting, but the opposite order is possible. We do not know with certainty how the five grand canvases brought down from their previous allocation in the Castle were arranged on the two walls, but the anagogical leading thread was undoubtedly one: the opposition of Good against all the errors of humanity. The Good assimilates in itself the activities of the biblical intellect and conscience, effectively amalgamating classical culture and its examples with Christian humanism the bearer of ethical, virtuous sovereignty. We do not resume the orderly display of the pictorial subjects and do not want to repeat their explications, already abundantly provided by an adequate critical literature. Here we deal only with the twofold conclusion that Isabella entrusted to Correggio.

First of all, this is an inseparable coupling, where pictorially the two figurative groups in their internal composition are placed on a proda, beyond a rìpidescendimento in the foreground: such a setting offers the sense of a “no return,” or rather a definitive condition. Above the groups stand airy openings. TheAllegory of Virtue or Wisdom has a character more markedly marked by upward directrices: here the composition passes from the habitable earth to the atmospheric sky and then explodes with impetuousness into a golden splendor vivid with spiritual emphasis where the theological Virtues sail triumphantly.

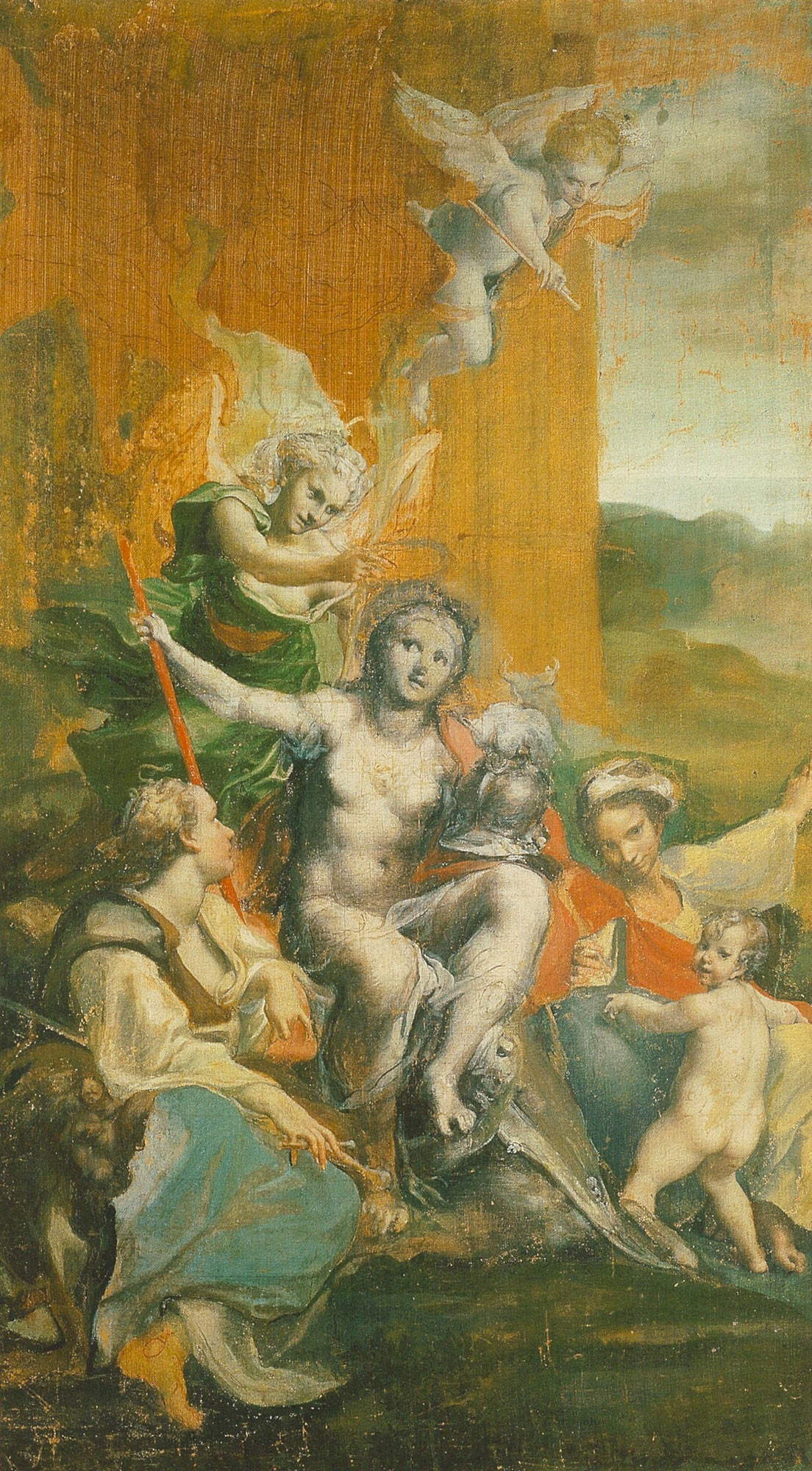

But before turning to our semantic analysis we think it is good to turn to the fascinating subject, preserved in the Doria-Pamphilj Gallery in Rome, which is undoubtedly an early effort by Correggio on the subject, left unfinished it is said probably for technical reasons but perhaps because of that impulse of continuous solicitation that always urged the painter to “see himself in the work” and thus to try again, as we can recall in the shuffling between sketches, tablets and drawings on several other creative occasions. The presence of another proof already in Palazzo Altieri, on panel, also supports our thinking. There is ample discussion of this in the essay “LAllegoria della Virtu? Doria-Pamphilj”: technical and critical notes by Diego Cauzzi, Andrea G. De Marchi, Pietro Moioli, and Claudio Seccaroni; which can be found in the Proceedings of the 2008 Study Conference at the Associazione Amici del Correggio. It says: Correggio’sThe Allegory of Virtue in the Doria Pamphilj Gallery arouses particular interest for two reasons. The first lies in the incompleteness of the work, which allows for a better understanding of the genesis and the manner of proceeding held by the painter, triggering conjectures about the reasons for the interruption of the work and revealing the starting nudes. The second concerns the technique, that of tempera on canvas, which was already employed in the Middle Ages, registering a special frequency in the Po Valley area, especially in the circle of Mantegna, that is, in the very world from which the young Correggio moved.

In that essay, rich in deep and very careful scholarly analysis, which included the Rome exemplar and the two in the Louvre, the text concludes by admiring Correggio’s preparations and highlighting the relatively conspicuous thickness of the pictorial layers of the Doria Pamphilj painting. This seems to connect organically to the final Louvre redaction, given the presence of preparatory layers whose consistency enabled Correggio’s canvases to achieve an extraordinary smoothness of color. We add to it the note of that “pre-eighteenth-century” grace that is the admirable surprise of this Allegrian exploit.

Let us therefore proceed further with this critical recovery that we find very useful. In the painted cover of the Camera di San Paolo in Parma (1518-19) Correggio had succeeded in combining myth and biblical-Christian tradition according to the complex thoughts of the abbess Giovanna Baroni da Piacenza. We must consider such an extraordinary fresco, rich in vivid semantic moods, as a close and earlier expression that certainly helped the painter in fulfilling the subsequent and demanding requests of the Marchioness of Mantua for the maieutic completion of her new Studiolo: also this locus explicationum for obvious task.

To arrange in a canvas of no great size (149 x 88 cm) the Three Theological Virtues, the reference to the Four Cardinal Virtues, certain elements of knowledge, the crowned protagonist, other significant figures, and to do so clearly, was undoubtedly an arduous task, which only the genius of the artist succeeded in solving with impetus and refinement. We know, for example, that in front of a painting our eye first rests on what is in the center, and Correggio does not forget this impact. In our case by tracing the two diagonals of the painting the central point of the whole composition falls on the mouth of the beautiful Woman who has for us an expression of great loving-kindness: the protagonist is in fact shown as the Allegory of Wisdom; to whom (more than likely) Isabella d’Este Gonzaga wanted to be likened.

Correggio, The

Correggio, The

The “Virtue par excellence” from which her sisters emanate, is in fact Wisdom, and Correggio (in certain dialogue with the Marquise) depicts her as the Minerva of the Romans. She is not here exactly like the Athena of the Greeks, goddess also of war, for she has laid her shield adorned with the terrifying Gòrgone on the ground, has her pole broken, and has taken off her feathered helmet surmounted by a Sphinx, a symbolic figure of fierce “dullness” that can only be overcome by study and sagacity. The leg of the goddess is finely adorned with a schiniere covered by the spotted cloak flap of a feline, culminating below the knee with an eerie human head: the flap could be of lynx skin, an animal symbolizing speed, intellect and vigilance over man because of its keen eyesight. It should be recalled that Correggio in the Camera di San Paolo had used a similar fur for the quiver carried by a putto on the east wall, and he would take up the mode on the same dart sheath in the sumptuous erotic painting, also by Mantua, of Venus, Cupid and a Satyr (1526-28) now in the Louvre. Isabella for her part wanted to wear an equally spotted fur coat in the late portrait she had painted by Titian! Thus we caught a round of assonances that should be symbolic and not accidental.

Another thematic connection with the Chamber of St. Paul, between myth and scriptural truth, Correggio maintains in the ideal superimposition of the figure of Wisdom herself, who here presents herself as Minerva but who lately impersonates Mary, the “Sedes sapientiae” of the Christian faith.

Correggio still does not cease to amaze us, however, because other symbolic elements appear in the painting. Behind Minerva (Wisdom) stand two columns formed of cedar branches supported by intertwining reeds: a pictorial virtuosity such as he had already done in the vault of the Camera di San Paolo in Parma. Other similar columns are visible to our left, that is, to the right of Wisdom, which is also the geographical part where the Holy Land is located. Following a probable Isabellian thought, we recall that King Solomon had asked God for the gift of Wisdom and had the Temple of Jerusalem built with columns and coverings of fine cedar wood from Lebanon. We should also keep in mind that the cedar, along with the palm tree, symbolizes the Virgin Mary, an incorruptible and eternal figure: as is ideally the longevity of these trees.

Reconsidering the diagonals of the painting, which find their meeting point at the mouth of Wisdom, the diagonal that closes the right side by encompassing all the earthly figures intersects a small shell with a pearl, placed to adorn the head of the Supreme Virtue, like the one Diana wears in the Chamber of St. Paul and which there depicts chastity. We can thus hazard the hypothesis that Wisdom standing at the foot of a cedar tree, adorned with a pearl in the shell, is symbolic of the womb that holds a precious treasure; with one foot she crushes a dragon, a sign of evil, and alludes to Our Lady, an earthly figure chosen by God to redeem man through Him from sin. And it will be she, the woman of the Apocalypse, who at the end of time must finally annihilate the dragon. The latter in the painting already has its belly compressed to the ground and tries to fight back, but in vain, with the last strokes of its tail. The red pole, normally reserved for heroes, is broken according to the ancient signification of a finished and won combat. The clothes that cover the woman also echo those of Mary: the blue that is a divine sign and that antique pink that Correggio used several times in the Marian image. We note that every detail could not escape the mentality and strongly semantic demand of Isabella, that is, of the most imperative and scrutinizing patron of all time. Thus the signifying analogies continue.

Even the crystal, the symbol of wisdom that in the shape of a sphere adorns the sword of the Fortress, is traditionally the image of Mary crossed by the heavenly light of her Son remaining Immaculate. The evangelist Luke reports the episode where Mary found her 12-year-old son, Jesus, in the temple in Jerusalem disserting with the doctors of the Law, arousing wonders in them: among those cedar pillars stood the very one who was the supreme wisdom, the Son of God. Finally, we should not overlook the angelic figure hovering over the central one: the laurel wreath it bears connects perfectly with Wisdom, but the palm branch (a symbol of martyrdom and victory) should be referred to the one who suffered martyrdom par excellence by achieving victory over death: Christ, the pillar of conjunction between earth and heaven! Certainly Allegri first elaborated in his conversations with Isabella such difficult-to-represent concepts, and then in his painting he created the high figurative symbols proving himself capable of being cultured and ingenious.

The Cardinal Virtues (Fortitude, Justice, Prudence, and Temperance) are personified by an elegant but sober maiden who sits on the ground to the right of Wisdom who towers over and reigns over the figurative group: these Virtues are in fact closely related to the relationships between human persons. Moreover, the whole female ensemble placed at the bottom of the painting is by Correggio situated in a well-defined space: a square that the painter obtains from the reversal of the base side on the vertical, according to a typically Allegrian measure. The upper side of this square thus precisely touches the top of Wisdom’s head.

We know that the square symbolizes the four elements of creation: air, water, fire and earth. Correggio, instead of using four figures to represent the Cardinal Virtues, makes a striking and admirable synthesis in a single maiden who carries four symbols: Prudence, signified by the serpent that stands on her head; the bite of Temperance in one hand and the sword of Justice in the other, where the importance of this virtue always being crystal clear is exposed by the vivid pommel that adorns the end of the sword. On the other hand, Fortitude, represented by the Lion, must never be overpowering but measured, which is why the maiden keeps it tame underneath.

More intriguing are certainly the figures on the opposite side, studied in different designs: a woman has a compass open on the globe in front of which stands a naked child. This woman has a darker complexion and is perhaps older, but more explicitly smiling; a series of bandages encircles her head (as in the “Cingana o Zingarella”) perhaps indicative of her traveling habit, and with her raised index finger she marks a distant place. It is commonly believed that she personifies the earth sciences. We can then formulate a hypothesis: since the New World had been discovered only a few years before, it is likely that Isabella, certainly attentive to such a resounding achievement, wanted to include it in her painting with the conviction that so much discovery resulted from enterprising human wisdom. Here the elderly woman could represent Europe, that is, the old continent that through travels found the new world, indicated and almost impersonated here by the naked Child, who, indeed, is uncovered: he, with his happy face turned toward the observer, marks with his left hand a discrete point on the globe. With a compass, resting on a precise space, the Woman measures the degrees of distances on the terrestrial sphere, and with her own pointing left hand, which comes out of the pictorial field, she seems to signal the discovery of a new, distant country.

Of great beauty and suave elegance is the angelic Genius who crowns Isabella with laurel and bears her palm. He has an extraordinary role in the demonstrative composition of the Allegory: he is in fact suspended between earth and heaven and fulfills the task of mediator-conjunctor between the two ideal worlds in which Isabella’s spirit hovered.

Returning to the Wisdom painting and having drawn its diagonals, we have graphically defined two equilateral triangles juxtaposed vertically. In order to obtain them we believe that Allegri finely studied the two geometric patterns “of perfection” that were absolutely adequate to the màntical roles of the figures to be inserted in them. In the upper triangle pertaining to Heaven (or better yet Paradise since the artist used a blazing burst of golden color) are placed the Three Theological Virtues, equipped with wings and well defined in their clothing by their typical colors: Green for Hope, Red for Charity, and White for Faith. Of the three Virtues, Charity is the most advanced, because as St. Paul says it is the most important and it is on this that we will be judged; in eternal life Faith and Hope will no longer appear, while what will remain will be the good accomplished, Love. These three Virtues hold two musical instruments: a lyre and a golden trumpet. In the myth, the lyre was a symbol of the cosmic harmony that united heaven and earth; to make the lyre vibrate was to make the world vibrate and tame the beasts: as we can see in the painting the Dragon being mastered by Wisdom, that is, trampled by her foot. The trumpet, which in the great celebrations associated heaven and earth, in the Christian sphere is found represented, especially in painting, in the scenes of the Last Judgment, the moment when the apocalyptic Beast will be finally defeated. In this painting, however, the trumpet is not stretched out to play but is turned backward, held by Faith and even more firmly by Charity, which does not want to make known the good bestowed. Before the terminal flaring of the instrument, Allegri has placed a carved figurine, equally gilded, that appears to play a bùccina, that is, a loud sounding shell that stands for the Word. Also important is the dominant and supreme glow that envelops and propels the Theological Virtues: one is struck by the exceptional strength of this divine flash that holds a force of eternity and does not fade into the earthly atmosphere as it does in other Allegrian works dilated between heaven and earth. Here the chromatic impetus is absolute, happy and reboant.

The landscape remains of a Leonardesque breadth, quiet and stretching from golden fields to diaphanous mountains, welcoming a mute distant city. It seems that distant cities in Correggio’s drafts have a prophetic and evocative character, just as we can see in other paintings: they always refer to the mystical “place of God,” the heavenly Jerusalem. In contrast, theAllegory of Vice or Insipience, which explicitly alludes to earthly vices, has a totally terrestrial setting, and for this reason it is set in a wide vegetal setting that offers Correggio (we must say) an airy and explained naturalistic song, forming one of the most beautiful “countries” in his painting.

The negative subject of the dissolute man, now old, is a demonstration of the end point of the exercise of vices in mortal life: the body, actor and source in its time of sensual enjoyments, is now weak and helpless against the results of them, and has become the seat of as many pains. In the extended symbolism of the group, man is bound to the same tree of life that appears as a fatal arbor; he is therefore helpless while the three Furies, all equipped with repellent serpents, engage in studied tortures. These turn in counterpoise to the senses already used to enjoy: sight, hearing, touch. The stretching out of the entire coloring makes this Allegory an achievement of full creative bliss: here the nudes triumph, Correggio’s beloved bodily nudity gathered in an almost “in a circle” composition that offers the mastery of screwed but totally graspable postures, and that barely subtends that luminous circle of bodies whose pivot is the now vanquished male member of the ancient wrestler and that includes (note) the recent split of the branch above his head: a stern sign of stinging reproof. From the tree hang leafy shoots of a fruitless vine.

Those who would eventually want to enter the symbolic recesses (coming perhaps from a cryptic Isabellian list) could elucidate on other aspects: on the three gratuitous but musical draperies of the furies and their colors, traceable to the vicious man’s disillusionments; on the shaggy goat skin where he sits; on the strip of slime where he rests his feet. But then, as introducer and caller, Antonio’s brush gives us that mocking brat, shoved down into the foreground of the slippery shoreline, and perhaps added to canvas still fresh, who offers us a most vivid type of tantalizing childish complacency, capable of unparalleled winking. We observe the bunch of grapes whose cluster has been emptied of berries, which by way of a sling the cross-eyed brat shows us as a symbol of the effects of wine. The ground is pervaded by the kind of creeping ivy that is sterile. All next to the large spike of polished rock, in a chromatic context whose form and pigments give lively work to the most decrypting investigations.

If the Allegory of Vice were the image that closes the entire Studiolo series we would be confronted with the sàpid farewell of that Po Valley genius who at this date still signed himself, smiling, “Antonio lieto.”

We had cited the Camera di San Paolo as Correggio’s first masterpiece of cultural breadth in Parma and now, at the conclusion of the semantic analysis of this painting for Isabella’s Studiolo, we can confirm how there are several elements in common that also corroborate the chronological proximity of the two works: the interweaving of the bamboo canes, the shell with the pearl, the figure of Minerva with the pole, a shield with the Gorgon, the spotted fur and the whelk. A skillful thread of forthright allegrian flavor.

Some conclusions that appear here are already present in Giuseppe Adani Correggio. The genius, the works, Cinisello Balsamo (Silvana) 2020, pp. 137-150. For biblical-mythological analogies see by Renza Bolognesi Correggio. The Camera di San Paolo. Unvelamenti inediti, Cinisello Balsamo (Silvana), 2018. Important closer or specific works on Isabella and her Studiolo. See by Stefano L’Occaso, Il Palazzo Ducale di Mantova, Milan, 2002.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.