“He who lives in the dream is a superior being, he who lives in reality an unhappy being.” These are the words of Alberto Martini (Oderzo, 1876 - Milan, 1954), an artist among the protagonists of the Belle �?poque, as well as among the most underrated names in early 20th century Italian art. An eclectic, eccentric, surprising, mysterious artist, he had written this phrase, in his autobiography, first of all to refer to himself, since in his account we read something like “my life is a daydream.” But in all likelihood he was also referring to the characters, as unconventional as he was, with whom he loved to surround himself. These included Luisa Casati Stampa (born Luisa Adele Rosa Maria Amman; Milan, 1881 - London, 1957), the femme fatale par excellence, the woman who symbolized decadentism, the “divine marchioness,” as Gabriele d’Annunzio (Pescara, 1863 - Gardone Riviera, 1938), with whom she had an affair, called her: born into a family of wealthy Lombard industrialists, of shy and introverted temperament, she found herself orphaned of both parents when she was only fifteen years old, and shut herself away even more, preferring the company of her drawings and her reveries about magic and esotericism in which she had begun to take an interest as a young girl. Then, at the age of nineteen, her marriage to Marquis Camillo Casati Stampa of Soncino, just two years her senior, an aristocrat, with whom she began to frequent the high society of the Milan of her time. And it was during these encounters that she began to change her character and become closer to the artists and literati who frequented the salons of early 20th-century Milan.

Alberto Martini was one of the artists to whom Luisa Casati became closest. She met him in all likelihood in 1904: for the past ten years or so, the Venetian painter and engraver had been embarking on a successful career as an illustrator, and had devoted himself above all to the illustration of great masterpieces of literature (his drawings for Dante’s Commedia, begun in 1901, are particularly remembered). He had already exhibited, four times, at the Venice Biennale, his drawings had been taken to several exhibitions around Europe, and in 1904 he was fresh from the success one of his exhibitions had achieved in London. It was then that the artist decided to move to Milan. And Luisa Casati had probably heard about him through Gabriele d’Annunzio, whom she had met at that same time, perhaps during one of the regular hunting trips that Marquis Casati Stampa gave on his estates around Gallarate. D’Annunzio and Martini shared the same passion for eroticism, the unusual, and literature, and the poet, as soon as he got to know his works, had no difficulty understanding their value. For him, the Venetian artist was the “Alberto Martini de’ Misteri,” as he called him in a letter sent to Vittorio Pica. And not only that: there is also a certain magical dimension that unites the two artists, with the divine Marquise at the center. “If in D’Annunzio,” literary critic Ferruccio Ulivi had to write, “a magical-esoteric-surrealist coté was carefully managed at the margins of a dazzling literary spectacular enterprise, Casati, who was his friend, was in some way its profane stand-in.” And it is perhaps for this reason that Luisa Casati became the perfect muse for Alberto Martini. In one of his articles for La Tribuna, D’Annunzio had written that “only music is given today to express the dreams that arise in the depths of modern melancholy, the indefinite thoughts, the limitless desires, the causeless anxieties, the inconsolable despairs, all the darkest and most anguished disturbances that we have inherited from the Obermanns, the Renés, the Jocelyns, the Guérin, and the Amiels and that we will transmit to our successors.” This evocativeness could also fully describe Alberto Martini’s art and Luisa Casati’s own life.

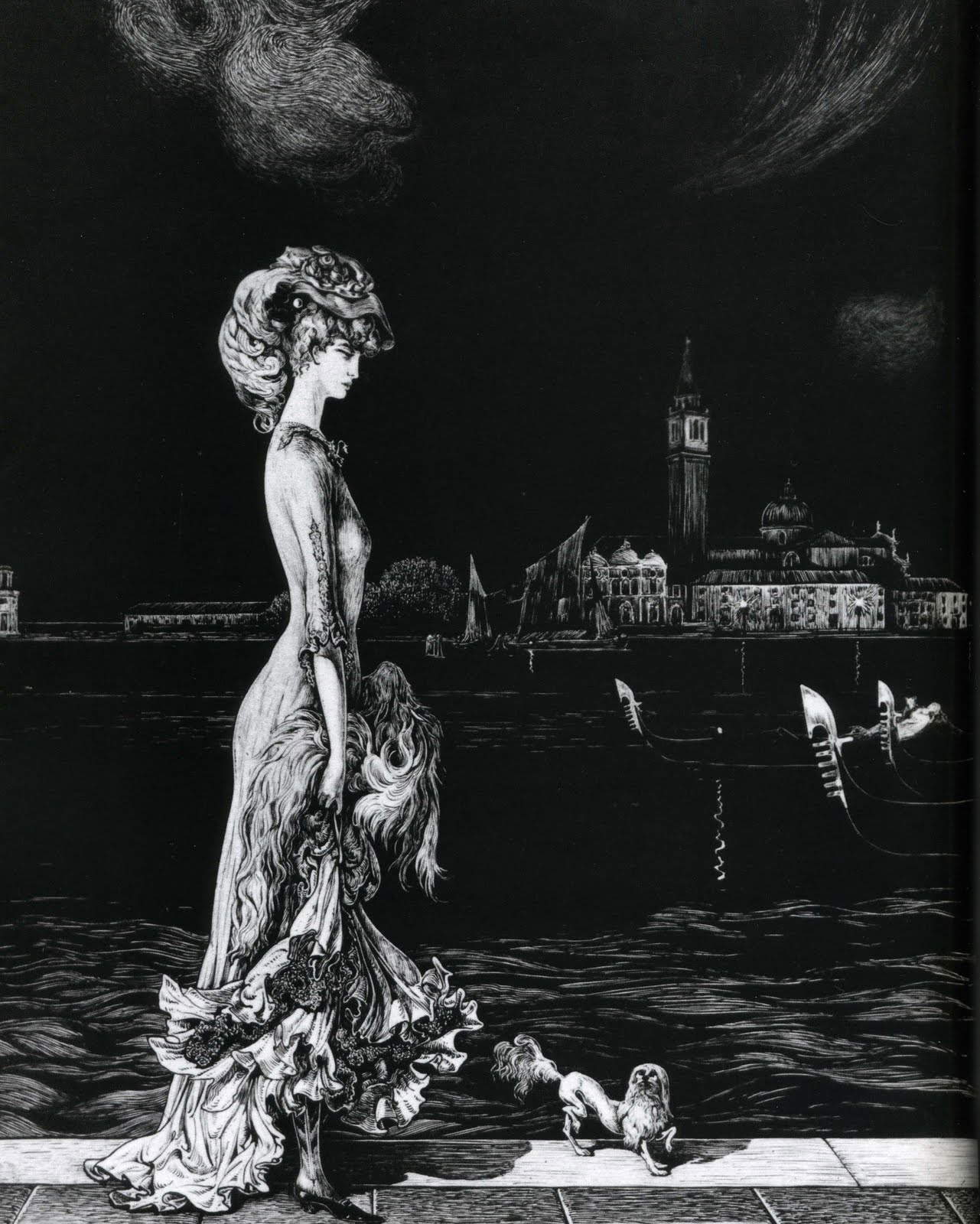

In those years, Martini was going through a phase of his production that Giovanni Papini would render with the adjective pair “erotic-fantastic.” The same ones that could describe the first portrait the artist executed of the marquise. It was 1906, and for some time Luisa Casati had been staying in Venice, where she would later move in 1910, when she purchased Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, the same residence that later belonged to Peggy Guggenheim and that today houses the museum that houses the collection of the great American collector. Her passion for Venice had been passed on to her by Gabriele d’Annunzio, and the city became lent a kind of stage on which the marquise loved to perform. Especially at night, especially in St. Mark’s Square. The setting Martini chose for his splendid lithograph, which gives us an exact portrait of how the marquise wanted to appear. Elegant, mysterious, seductive, independent, almost disturbing. We see her as she strides, in a tight dress that accentuates her very slender (and studied) form: her conspicuous thinness, which was combined with an uncommon height, was considered a flaw according to the canons of beauty of the time, and hardly appropriate for a woman: her physicality therefore also embodies her freedom), with a bony Pekingese, at night, in a ghostly Venice. Lonely, she walks along the riva degli Schiavoni in the direction of St. Mark’s, with the island of San Giorgio in the background, a few gondolas on the basin of St. Mark’s, and in the distance a raft with frayed sails, seeming almost to be led by ghosts. “Very tall, very thin, her face devoured by huge bistrate eyes,” Ulivi writes again, “she had come to personify in every way a decadent repertoire between ’black’ and bewitched, from Khnopff to von Stuck, from van Dongen to Klimt.” Due in part to the extraordinary nature of her figure, artists would do anything to portray her, and one cannot count the painters and sculptors who elected her as their model.

|

| Alberto Martini, La marchesa Luisa Casati (1906; lithograph on paper, Private collection) |

The first portrait executed by Martini is a kind of statement, rendering with exceptional effectiveness the image that Luisa Casati wanted to give of herself. And it is interesting to note that the artist did not only execute portraits in the image of the marquise: he also had a way of talking about her in his writings. In one passage, for example, he writes about her in these terms: “the marquise lived partly as a slave to her dream world. She had two vices: her palace and her aristocratic circles. They served her as a stage where anyone could be an actor, but when she entered, everyone automatically became a spectator or additional element.” The element that divides Martini from many other artists who made portraits of Luisa Casati (famous above all is the one with her dogs made by Giovanni Boldini) consists in the fact that the painter from Oderzo was endowed with an uncommon dreamlike imagination. And since the marquise was also “a slave of her dream world,” perhaps no other artist was better able to penetrate this world. In reality, the marquise’s dreams took the form of disguises, eccentric costumes, exotic animals, masquerade parties, and walks in the middle of the night in a silent Venice, one of which would be described by an unsuspected Margherita Sarfatti: “Two nights before, after Marchesa Luisa Casati’s Persian fête, St. Mark’s Square silent, between rose and gray in the dawn lights, had awakened to a prodigious dream of masks; at the head of them all the Marchesa, with parrot on her fist, in the fairy-tale princess hairstyle devised by Bakst for that inventor of exquisites. Never Carpaccio, never Paolo Veronese or Gentile Bellini had depicted more splendid company in the calli and along the canals already iridescent with millennial grandeur.”

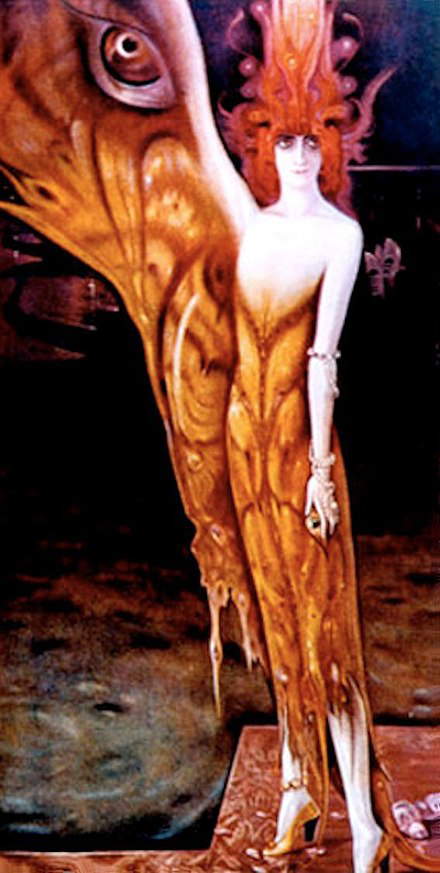

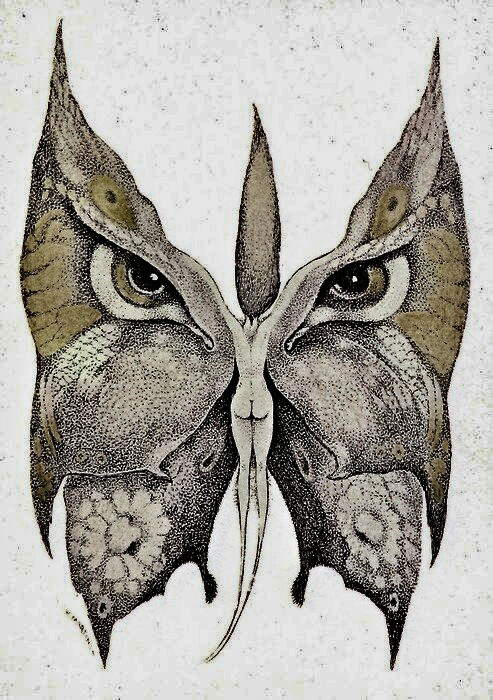

Alberto Martini’s decadent temperament wanted to preserve the memory of this eccentric and out-of-the-ordinary femininity, and in the years leading up to World War I, the artist executed a number of portraits of the marquise depicting her with her body undergoing mutations, with her turning into a butterfly and flying over the canals of Venice, as happens in Un lent réveil après bien de métempsychoses (title borrowed from a lyric by Verlaine) or in Diamante - Butterfly of the Night. Exactly like the butterfly, the marquise wanted to embody the likeness of a being with a hybrid nature, and like the butterfly, Luisa Casati knew how to be graceful, feminine, frivolous. But there was also a reflection on the transience of existence, given also the ephemeral life of the butterfly: it is that boundary between life and death that animates decadent aesthetics. These portraits would have moved the attention of the aforementioned Vittorio Pica: “evoking against a picturesque backdrop of nocturnal Venice, the tall, slender person and intensely expressive face of Marquise Luisa Casati, he made of her, yielding to a whim of his ever-boiling imagination a strange and mysterious creature of fairy tale, half woman and half butterfly, who recalls in the mind of the one who contemplates her a little while longer that verse of Paul Verlaine of such subtle suggestion, which speaks of a lent réveil après bien de métempsycoses”. And Martini was well acquainted with Verlaine and the French Symbolists, since it was precisely in the 1910s that he produced some works inspired by their compositions. The seduction and fragility of the butterfly are elements that also appear in Verlaine, but to that totally dreamlike dimension of the French poet, Martini replaces an image sustained by a living and present physicality, which can be seen beneath the tattered robe in the form of long legs and feet wearing heeled shoes and arms displaying flashy jewelry. “A portrait,” wrote Dario Cecchi, “that certainly began to establish an aura of legend around the Casati character.”

|

| Alberto Martini, Un lent réveil après bien de métempsychoses (1912; pastel on paper; Turin, Private Collection) |

|

| Alberto Martini, Felina (1915; black and white lithograph, watercolor by hand, 13.5 x 10.7 cm; Oderzo, Pinacoteca Alberto Martini, Fondazione Oderzo Cultura onlus) |

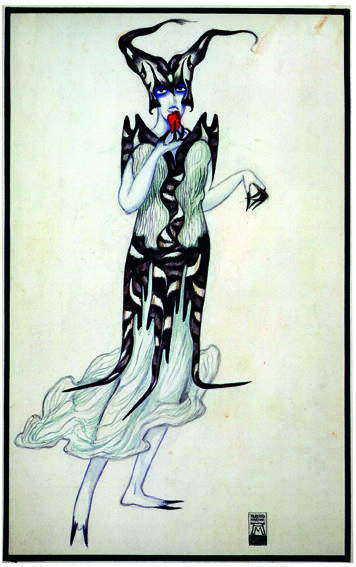

|

| Alberto Martini, Jealousy (1919-1920; tempera on paper, 310 �? 190 mm; Collezione Ines Grignani Anderloni) |

A legend that Martini, even today, continues to nurture with his own writings. Even the signing of a contract became a kind of performance. “She posed as a great artist, and as a great lady, for the greatest artists in the world,” Martini had written. “In a wing of her Parisian palace she had a gallery of beautiful portraits. From 1912 to 1934 I made twelve portraits for her, and she wanted them bigger and bigger; I thus reached the height of three and a half meters. I had to work on two ladders joined by a canopy. Her parrots also climbed there with me, and flying on top of the antenna where I had to balance myself, was a large Grand Canyon bird. All around, a row of very large silver and gold chairs, and lion skins for the aristocratic guests and performers. The show was fun and acrobatic! The vernissage of the three large portraits, was a magnificent ball that cost her a million. Of 1912. Foreign guests came from England, Germany, Italy and America. Every year I had to go to Paris, and if I didn’t go he would come by and invite me to Milan. Once even with the lawyer, to draw up regular contract, with deadlines and advance and travel expenses for me and my wife, nor was there any way to change the system. The contract was signed by the parties, in duplicate, in a very hot room. The marquise entered and stood, hieratic like a Byzantine majesty, in a gold and pale pink costume, her favorite colors, studded with gems, pearls and glittering crosses. Her eyes as still as enamel. In the center of the hall, a low couch covered with a mournful black velvet drape and above it stretched a naked dead man. When I entered it looked to me like a corpse, but I was prepared for anything. It was a divine dead, a deposed Christ carved in ancient ivory, vividly illuminated. [...] Thus the great artist had transformed the banal apartment of the great hotel into a theatrical mystery.”

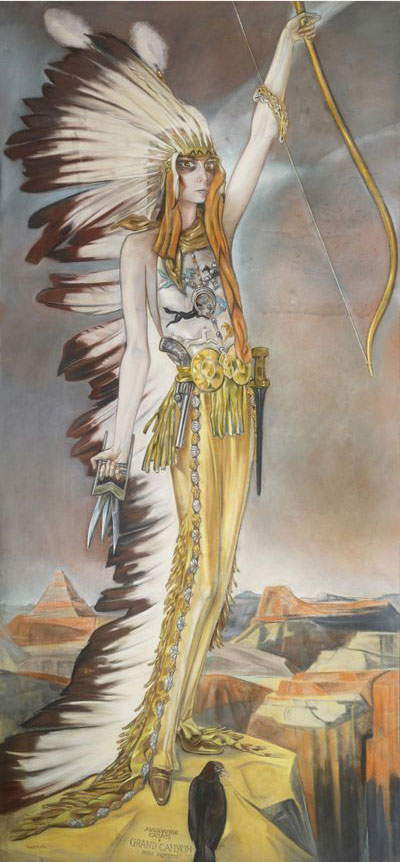

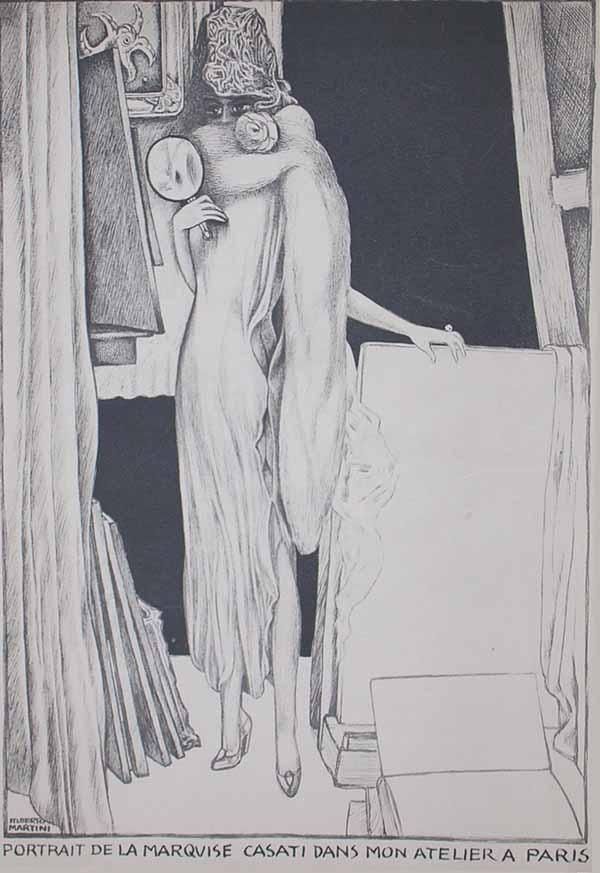

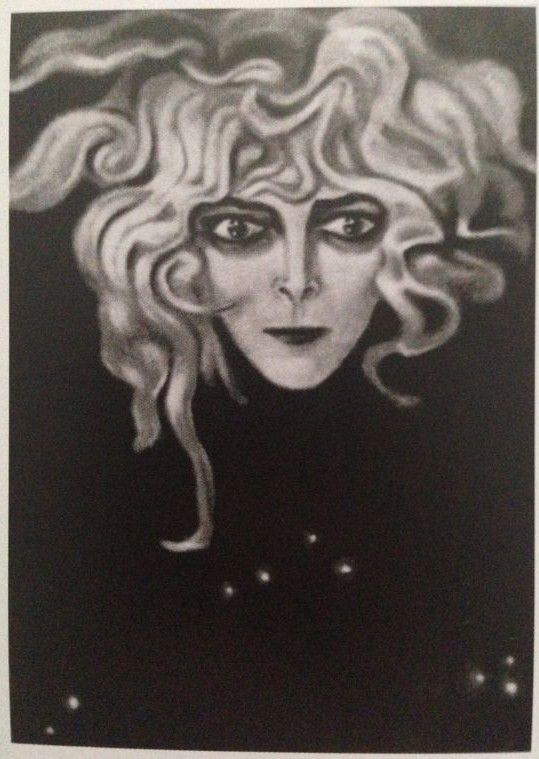

Some of the portraits mentioned by Martini are as bizarre as a noblewoman could then wish for from an artist. In one of them, the marquise had herself portrayed in costume by Cesare Borgia in a salon of his Paris palace. And it is one of the huge canvases of more than three meters to which Martini alludes in his writing. Then there is the portrait “as a wild archer” in which she wears the clothes of a Native American. In yet another she appears dressed as the Countess of Castiglione. These were the costumes she had made for parties, spending absurd amounts of money. And then there is a drawing depicting her standing on a bank in Venice, leashing the cheetah she used to take with her on her sorties. Then there is the famous print in which the marquise is depicted in Martini’s Parisatelier, wrapped in a heavy scarf that leaves only her eyes uncovered. Behind the marquise we see another portrait of her, which depicts her in the form of Medusa: the mythological gorgon was one of the characters most frequented by the Symbolist imagination, and its symbolic references were well suited to the divine marquise’s bewitching personality. In portraits such as Medusa, Martini focused on Luisa Casati’s penetrating ga ze, a gaze capable of petrifying and that became a constant feature of the portraits of all the artists who had to paint or draw her. And she was well aware of this, given also the makeup she used that enhanced her large, wide-open eyes.

|

| Alberto Martini, La marchesa Casati as Cesare Borgia (1925; pastel, 280 x 125 cm; Audouy Private Collection) |

|

| Alberto Martini, La marchesa Casati as a wild archer (Grand Canyon) (1927; pastel on paper, 300 x 140 cm; Audouy Private Collection) |

|

| Alberto Martini, Portrait del la marquise Casati dans mon atelier a Paris (1925; lithograph on paper, 365 x 270 mm; Private collection) |

|

| Alberto Martini, Medusa (1925, photograph of the original dispersed pastel) |

Relations between Alberto Martini and Luisa Casati did not always go well. Of the fact that she considered his very existence a work of art, we can also see from an anecdote that takes us back to the Paris of the 1910s. “Some friends,” the artist recalled, “including the managers of a large art gallery, wanted to make an exhibition of the portraits I had painted for the Marchesa Casati. In vain they worked for a year to obtain them. The marquise did not want them, protesting that mine was not studio art and that she would never allow such a popular exhibition. In that case I lost a fortune, for the curiosity was great. But fortune worth in the face of the dignity of art, he added!” One might therefore wonder why the Marchesa Casati lent herself to being portrayed in the most daring poses and costumes, or, using the words of Dario Cecchi, one wonders why she ran the risk of “indulging in the more than indiscreet ravings of an artist and exposing herself to the ridicule of the people,” given that many often depicted her half-naked or in attitudes that were in any case considered entirely improper for a noblewoman. Perhaps simply her portraits are to be interpreted literally: “whether it was Cesare Borgia wielding a knife,” wrote Chiara Toti, “or the Countess of Castiglione, one of the women she most admired, she merely followed the multiple manifestations of her personality.”

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.