A double manuscript from the 13th century recounting the life of St. William of Vercelli

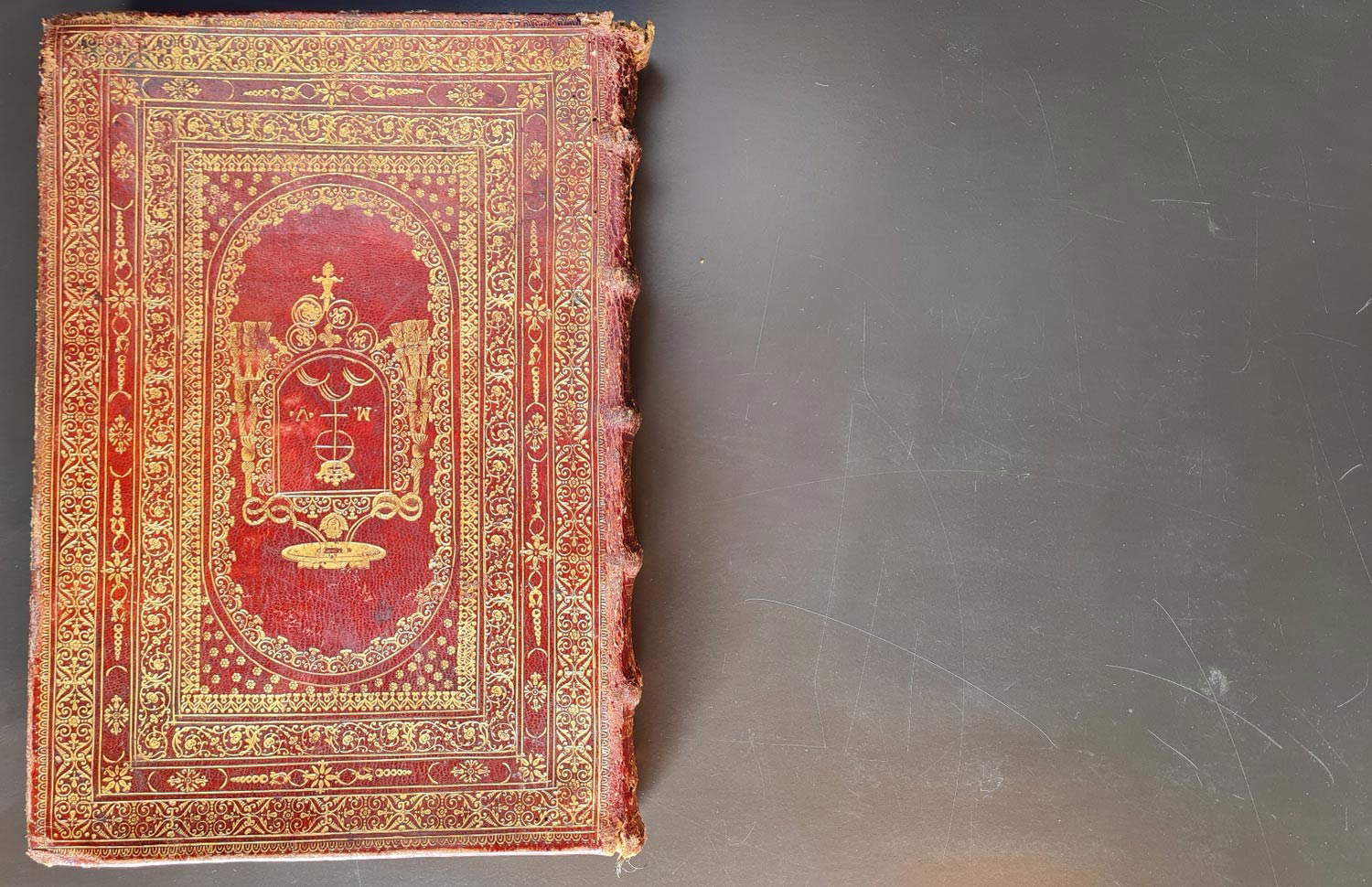

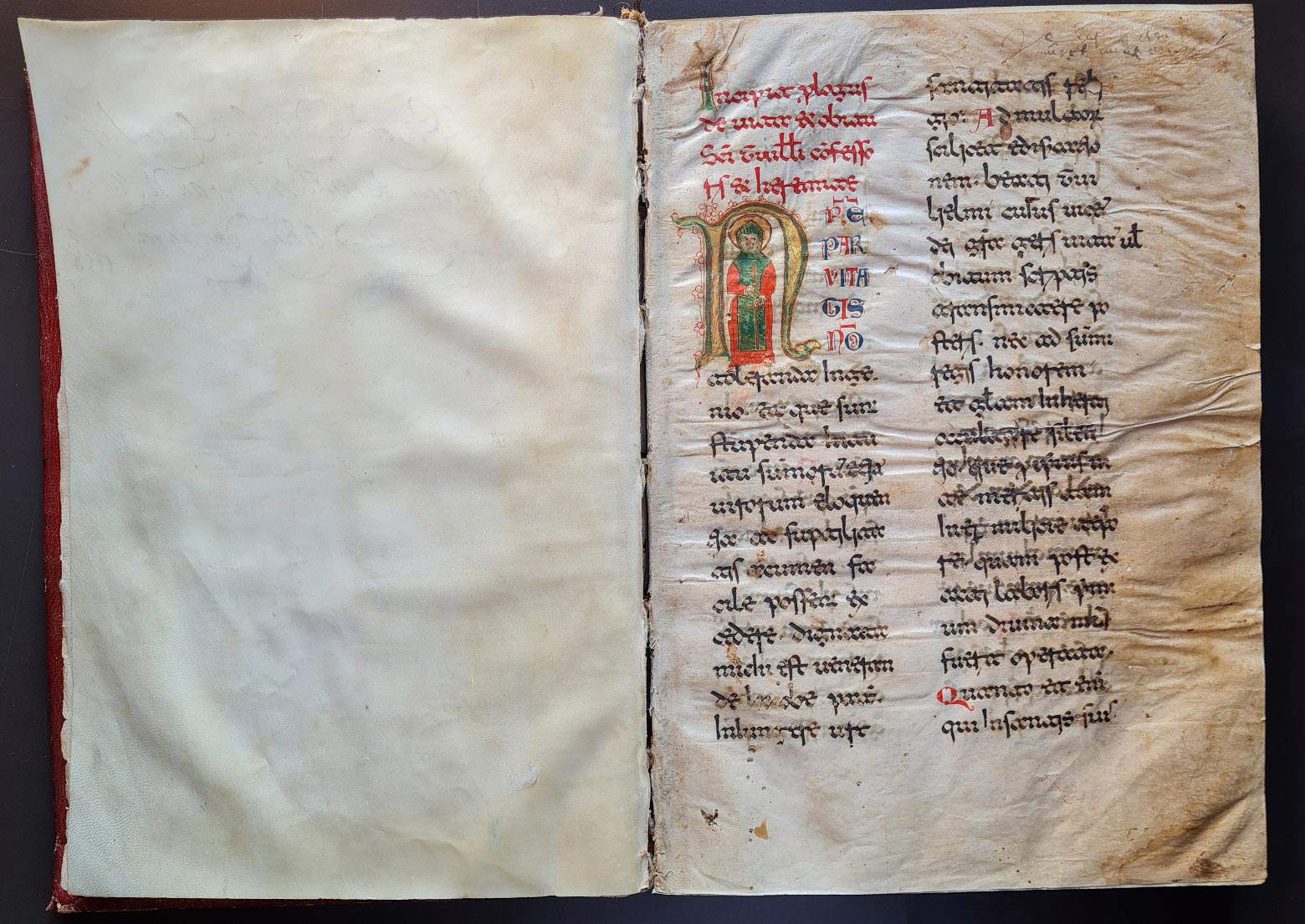

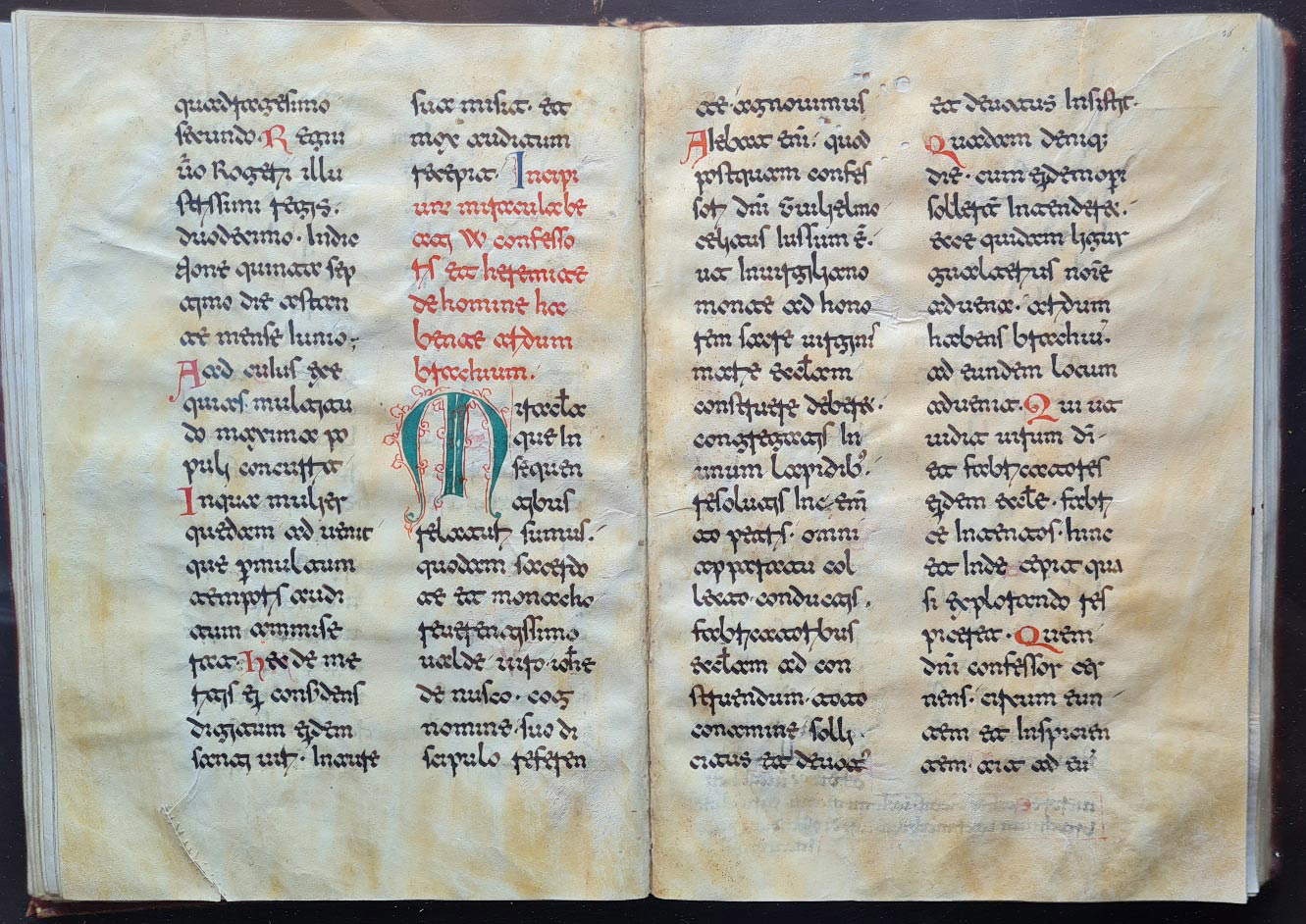

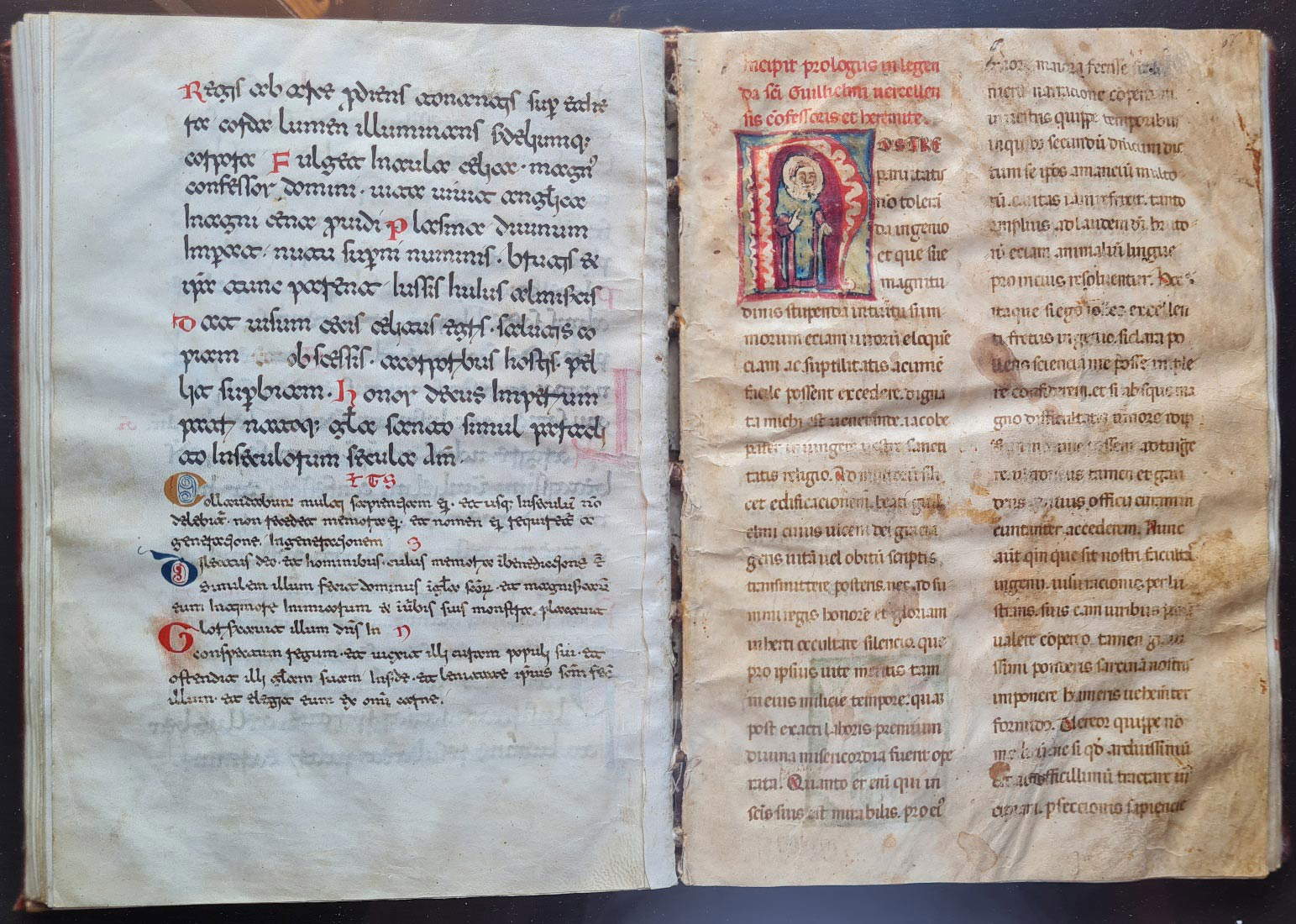

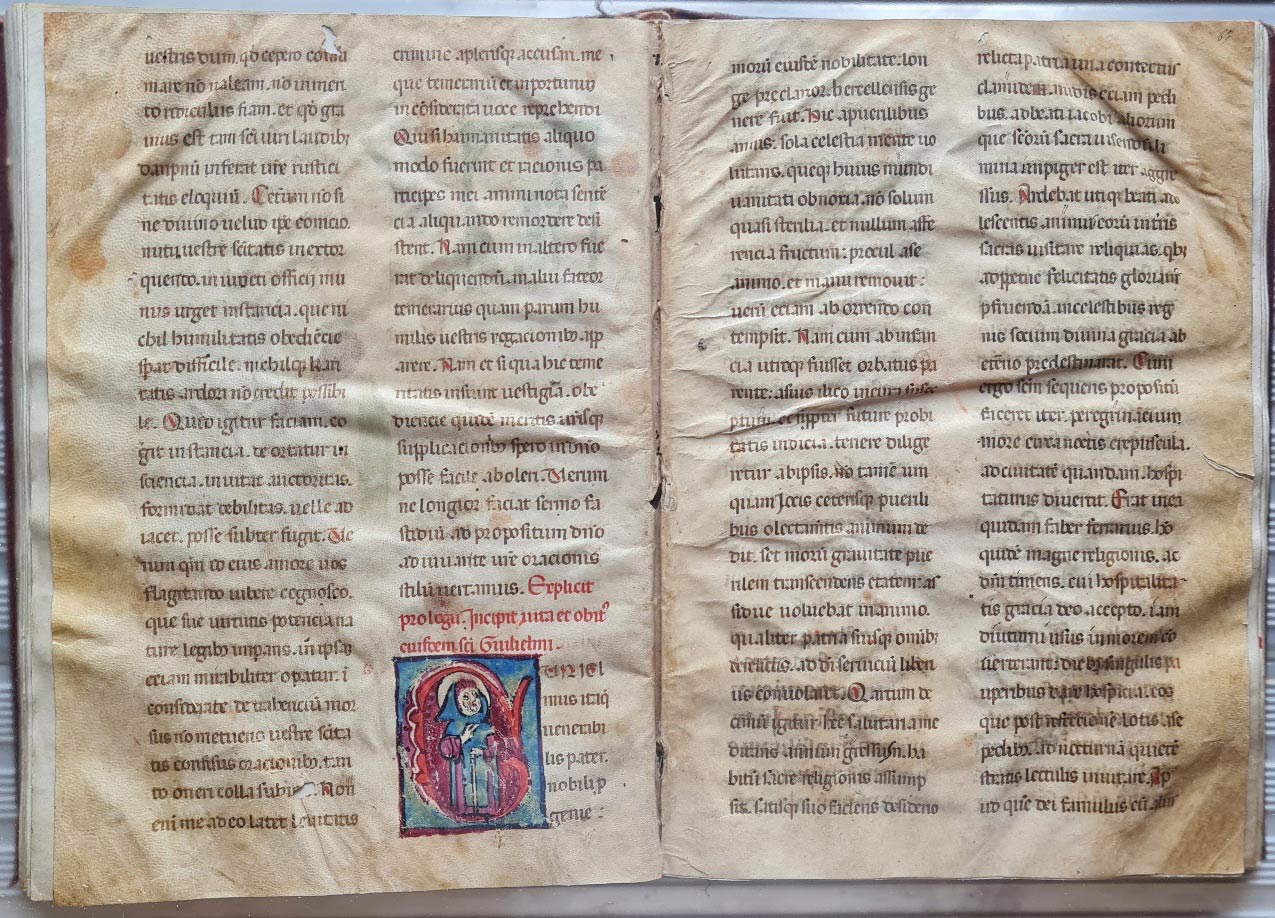

Manuscript number 1 in the catalog of the State Library of the Montevergine National Monument coincides with perhaps the best known and most studied manuscript in the library of the shrine of Montevergine in Mercogliano, Irpinia: it is the Legenda de vita et obitu de Sancti Guilielmi confessoris et heremite, which actually gathers together two manuscripts, one in Beneventan script and the other in Gothic script, brought together in a single volume consisting of 109 sheets remargined to give them the same size, and bound with a cover, dating from the seventeenth century, of red morocco with gilt friezes. The book, dating from the 13th century, recounts the life and miracles of St. William of Vercelli, also known as William of Montevergine (Vercelli, 1085 - Goleto Abbey, 1142), a wandering monk and abbot, founder of the Abbey of Montevergine. The Legenda recounts the travels and miracles of St. William, who is followed on all his journeys: his pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela to see the relics of St. James, his journey to Italy with the intention of going to Jerusalem, his stay in Atripalda, and his stay in Montevergine.

Precisely the parts of the Legenda that focus on Montevergine give us an interesting view of the birth and early stages of the Irpinian monastery, which was founded by William and which grew in size precisely because of his fame as a thaumaturge, since many monks wanted to settle in Montevergine to see up close the miracles of which the founder was capable. The fame of sanctity that already surrounded his figure did not sit well with William, who had initially embarked on his journey to southern Italy partly to escape this situation: he would change his perspective after meeting St. John of Matera, who sent William, explains scholar Orazio Limone, “to be more sympathetic to a choice of life devoted to evangelization and love of neighbor and not only aimed at mortifying his own body in the desire for God.” John of Matera thus convinced William that one can also be close to God by spreading his word and remaining close to the faithful. The young Piedmontese, initially unconvinced, resumed his journey, but he soon had to reconsider and it was not long before he interrupted his life as a hermit to live his life as a Christian in community.

The

The

At Montevergine, William needed to organize the community, and in this regard he disciplined the monks with his regulations: in particular, he stipulated that all monks were to work “propriis manibus” to ensure the sustenance of the monastery, but the monks, while at first welcomingly accepting St. William’s “consilium,” soon reclaimed the right to devote themselves to the divine offices, which involved abstinence from work, and pushed to have the Church’s goods allocated to the monastery rather than distributed to the poor. William, perhaps so as not to fuel clashes, preferred to leave Irpinia for some time to travel to Bari in order to purchase books and vestments for the shrine, after which he returned to Montevergine where the brethren asked him to have a church built: the saint agreed, and the construction was finished in 1126. The library itself was founded at the very instigation of St. William, who convinced the brethren of the importance of having study tools: the scriptorium at Montevergine was started from the very copy of the books the saint had brought from Bari, on the back of a mule. The production of the Scrittorio Verginiano was intense and, according to Placido Mario Tropeano, who was director of the Montevergine library, was devoted mainly to history books, patristics and liturgical works. The Legenda itself could be a product of the scriptorium initiated by William.

The Montevergine manuscript has always been the main source for learning about the hagiography of St. William of Vercelli, so much so that the first attestation of the manuscript is also very old: in fact, we find the Legenda mentioned in the Martyrologium virginianum of 1492. The volume had a certain fame even in the age of the Counter-Reformation: the text, explains scholar Veronica De Duonni in her recent study (2022) of the material on parchment in the Library of Montevergine, “attracted the attention of scholars and scholars of hagiographic traditions on the impetus of the interests stimulated by the Council of Trent.” Hagiographies of the saint based on the Legenda also flourished at the time, which experienced renewed interest in the 20th century, a time when the work began to be scrutinized by scholars of ancient manuscripts, and in 1962 the first critical edition of the Legenda was published, the work of Father Giovanni Mongelli, who was also the first to deal with the decoration of the codex.

It was precisely Giovanni Mongelli who also studied the problem of the autography of the two manuscripts, which the scholar believed to derive from a lost antigraph (before him, on the other hand, the Gothic was thought to be a copy of the Beneventan, a hypothesis to be discarded because of too many inconsistencies). Because of the style and certain contents that can be read in the various chapters of the Legenda, Mongelli came to the conclusion that the hagiography of St. William must be the work of as many as three different authors: the traditional attribution to John of Nusco, a disciple of St. William, who had previously been recognized as the author of the entire Legenda, was thus questioned. Mongelli’s hypothesis has not yet been challenged, and therefore today there is a tendency to accept the idea that the work is due to three different hands.

The first author, to whom chapters I through XVI are attributed, must have been a monk who was unfamiliar with Montevergine, since his descriptions of the lands around the abbey are sketchy, plus his judgment of the monks is too harsh (“he rants against them,” Mongelli writes, “branding them insane, stingy, rebellious, people who distrusted God’s mercy”). On the contrary, the copyist is very precise when he speaks of the area where William founded the abbey of Goleto, the place where the saint disappeared in 1142, as well as reporting in detail the “austere and edifying” life of this monastery, which is thus put in a good light, as opposed to Montevergine. The conclusion, according to Mongelli, is that the first author must have been a monk of Goleto, and more cannot be added. Chapters XVIII, XX, XXI and XXII are attributed to the second author: in this case it is, according to Mongelli, a monk from Montevergine, since at the beginning of the eighteenth we read that the author learns the facts narrated directly from John of Nusco, of whom the same author provides, in the twentieth chapter, an “unforgettable” profile according to Mongelli, recalling how John was first a layman, and then a priest and great contemplative, who remained in Montevergine even after William’s final departure. Moreover, the second hagiographer appears better informed than the first about everything related to the Montevergine monastery. Finally, the third author, found in chapters XVII, XIX, XXIII, XIV and the Prologue: this would still be a monk of Goleto, since the parts contained in these chapters deal accurately with events that took place in this monastery.

The history of the two manuscripts, however, escapes us. The codex in Gothic type is unanimously considered to be the one of lesser value: it comes with a parchment of lesser value, with capitals in black, initials of no particular interest, and so on, which is why it was certainly a modest edition. And for that reason, the Gothic unit is much more worn than the Beneventan one: the stately appearance of the latter, in fact, “has almost always kept later hands away from touching the text of the ancient amanuensis,” Mongelli explains, “instead, the Gothic codex has seen numerous tamperings operate on itself, to which the too-frequent expunctions of the amanuensis himself have given the abbrivium.” According to Mongelli, the Beneventan codex was the older one, while Francesco Panarelli advanced the hypothesis that the copy in Beneventan script may have been produced at Goleto, on a par with the one in Gothic characters, and both would have come later to Montevergine to be united. There is, finally, a curiosity: in the Beneventan unit, in one of the illuminated capitals, an N, in gold outlined in green and red, is illuminated the figure of St. William, who appears with beard, halo, red cassock, scapular, pointed cap, while holding the cross with his right hand and a staff with his left (we find, moreover, a similar figure in the initial of the Gothic unit). It is a figure that certainly does not stand out because it is particularly valuable, indeed, it was made with a certain crudeness: however, it is interesting to note that the monk who was in charge of the decoration of this codex wanted, in his own way, to pay homage to the protagonist of the narrated story.

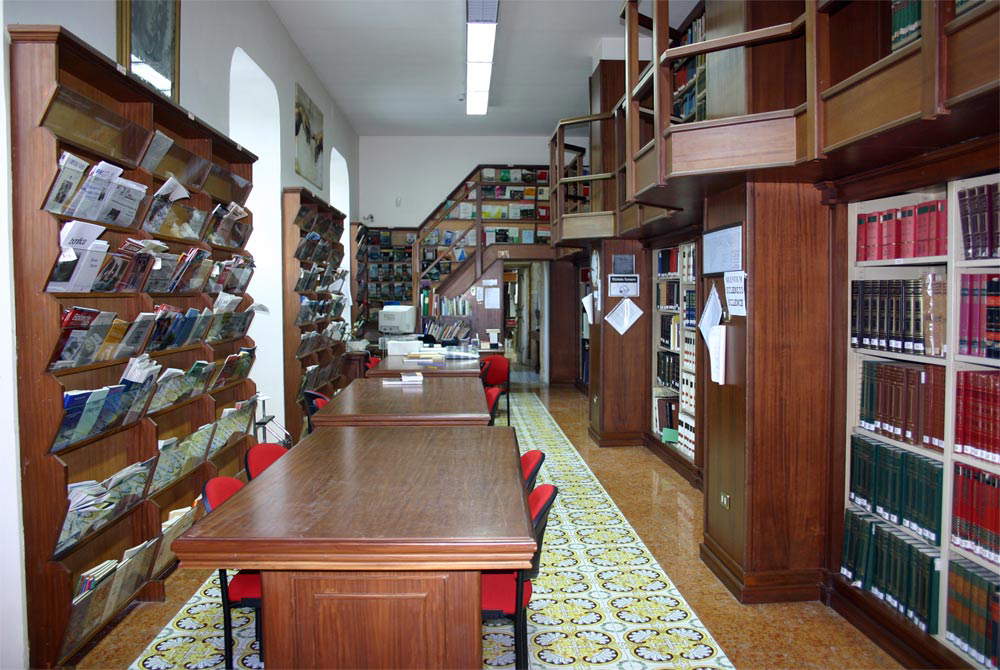

The State Library of the Montevergine National Monument.

This is the library of the shrine of Montevergine, founded by St. William of Vercelli in the early 12th century. It was started as a tool to support the research and study activities of the monks, and then, following the laws of suppression of religious corporations, came under the dependence of the Italian state, after Montevergine was declared a national monument in 1868. In the territory of the capital and the province of Avellino, the Montevergine Library, the only state library, represents a point of reference for research in the religious sphere, above all, but also with regard to all other disciplines. The library and the adjoining archive are housed in the 18th-century Loreto di Mercogliano Abbey Palace, a work of the highest architectural interest, designed by the Neapolitan architect Domenico Antonio Vaccaro. Today the library depends on the Ministry of Culture.

The holdings of the Montevergine Library, which are relevant to religious, social, political and economic studies, consist of manuscripts, incunabula and cinquecentine, music collections, more than 200,000 printed volumes from the 17th-20th centuries, 348 periodical titles and, among the archival material, 7,000 parchments and more than 100,000 loose documents.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.