It stands like a marble flower or a snow-white butterfly on the compact red-hot fabric of the ferraiolo brick that clamps the elevation of the comital dwelling erected on the golden principle of the 16th century to welcome sovereigns and most excellent guests in the heart of Correggio, a small and lively court of the Italian Renaissance. To adequately assess the surprise and admiration one receives upon discovering this Portal, it will suffice to recall the phrase murmured in enchantment by David Alan Brown, the great Leonardo scholar, when he came before it: “now I understand why a genius was born in this place,” and he was referring to his beloved painter, Antonio Allegri.

Anticipating the time to read the work itself it will be convenient to turn our thoughts to the two fathers who certainly wanted it. The first, Count Nicolò II of the Da Correggio family (1450-1508), highly esteemed and much in demand at the courts of the Po Valley; poet and dramatist, man of arms and master of delights, director of great feasts, carnivals and tournaments, rich in meaningful inventions, was the one whom his cousin Isabella d’Este Gonzaga stigmatized with the famous phrase: “the most apt knight and baron per rime et cortesie de li tempi sua.” This friend of Leonardo’s had grown up in his maternal ducal family in Ferrara and had become deeply attuned to Biagio Rossetti, the shaper of a city’s motions and the builder of courtly palaces set firmly on divine proportion, but all of which slipped into curious open desinences, such as obvious necessities of common living, thus moving away in modernity from the blocks of closed Tuscan architecture and related abstractions. In this way we have named the second father of our Portal, to whom Biagio directly gave the perfect form, the lightness of enchantment and the flowing score of a sculptural epilogue, evoking an ideal world of symbols and myths amidst glowing armor.

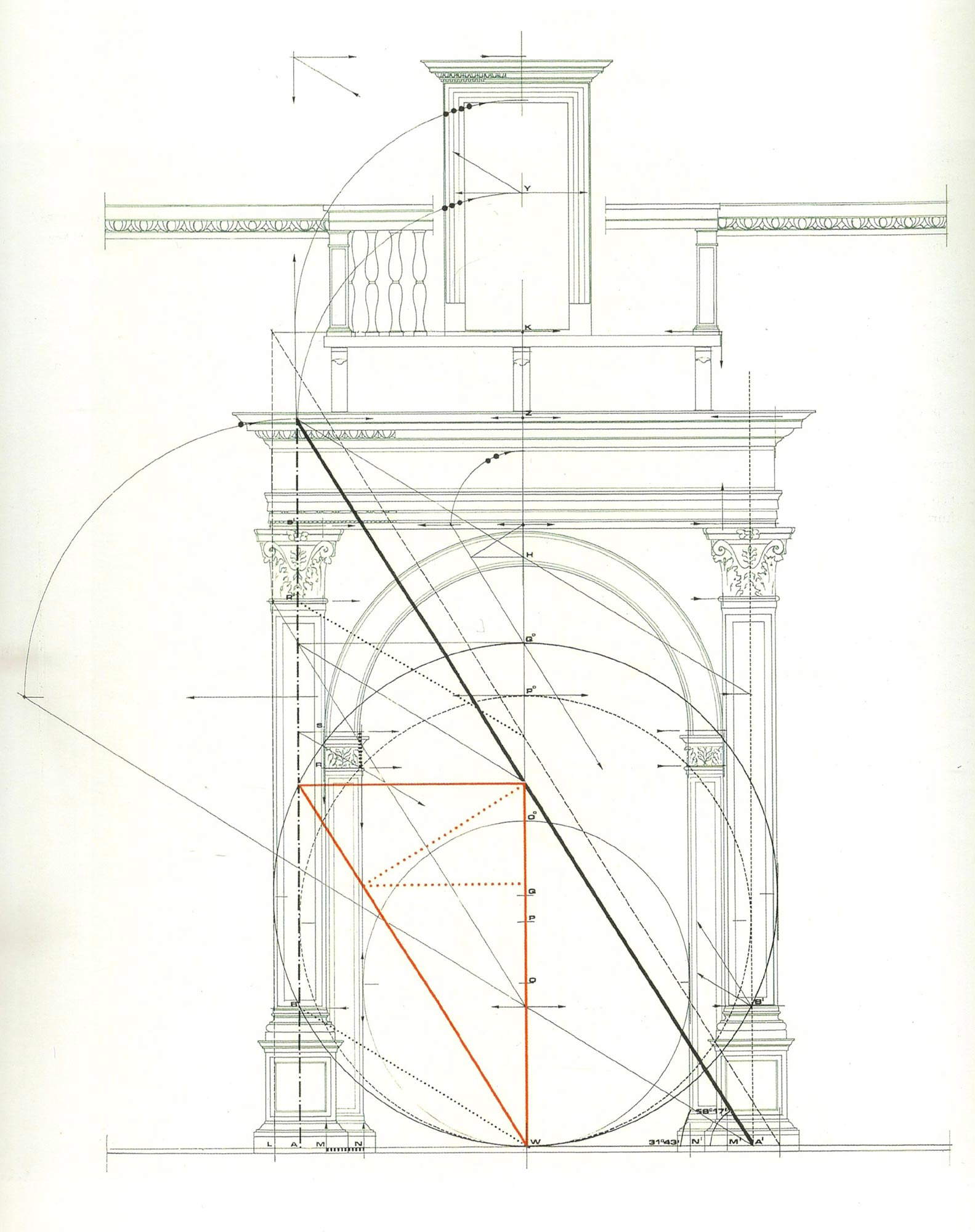

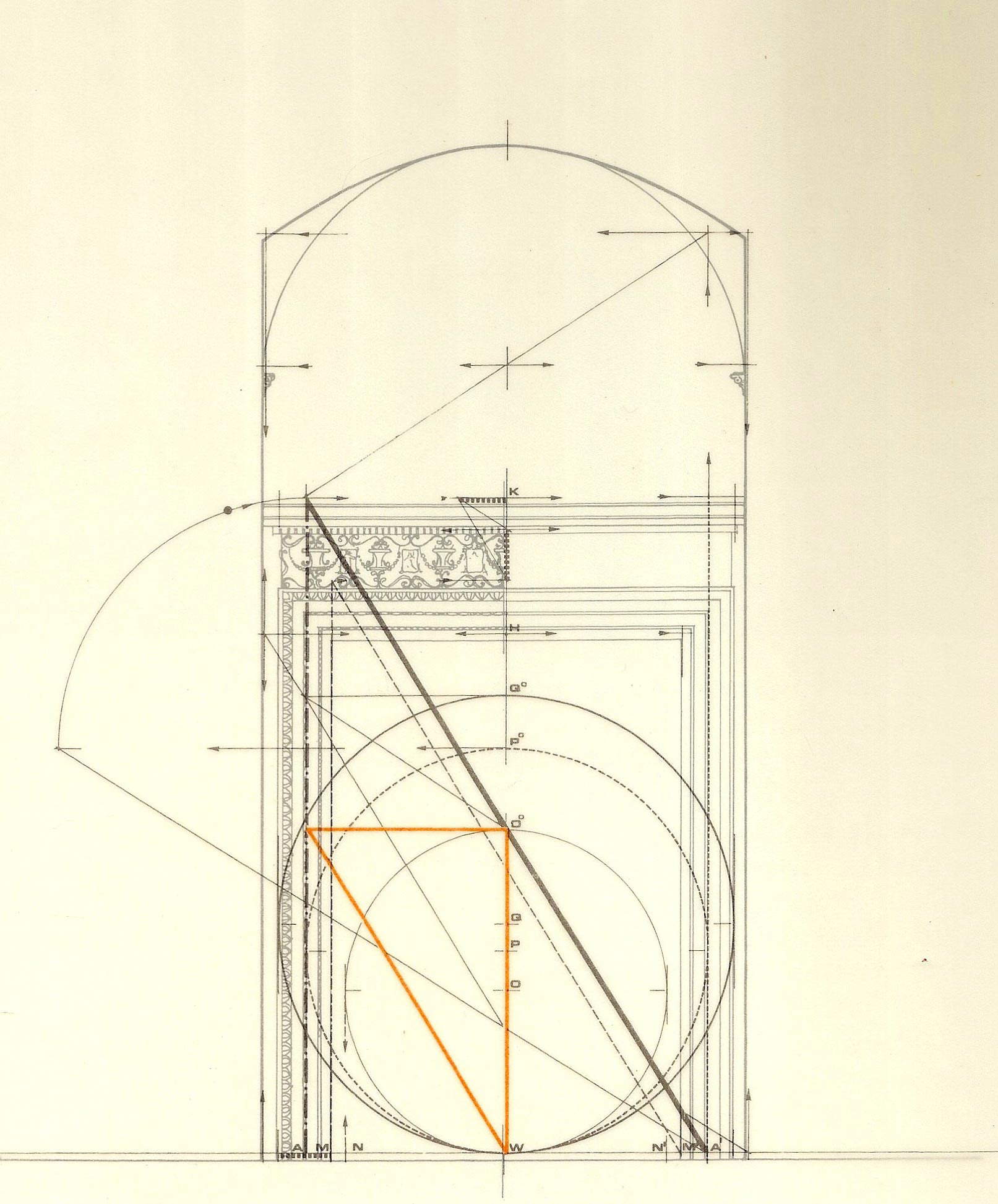

The admirable bi-ordinal setting of the artifact, in the “divine” proportionate ordering of its measures, by extension confirms the entire Rossettian architecture of the Palace as an exceptional project of the author outside the city of Este, and makes peaceful the arrival of the stoneworkers on that Venice-Ferrara line from which Istria stones and other marbles also arrived by waterways. The Portal of the Palace of the Princes in Correggio is the work of the first decade of the sixteenth century, elaborated around 1507 and led to its placement together with the colonnades with rich capitals, the cantonarias and their coats of arms. There are in fact two dates by which the project and at least much of the work had to be completed: in 1506 Antonio Lombardo moved his workshop from Venice to Ferrara (but he had previously been working here on the grand portal of the doctor Castelli and receiving other rich income from the court), and in 1508 Nicolò II da Correggio, the patron, died. It is easily conceivable that the Correggio count, a beloved cousin of Hercules I and now of the new duke Alfonso, may have had solicitous relations with Antonio Lombardo, probably already known in Venice, and that his request, corroborated by Rossetti’s superb design, played into the hands of the workshop, now amply equipped. Thus the commission for that Portal that was to go far from the ducal city stood alongside the celebrated engagements for the “alabaster diti chambers” and for the numerous candelabras and plaques that are still to be found in Ferrara’s palaces and churches: after all, the motifs and style coincide in evidence. We do not know whether most of the structural and sculptural work took place in Ferrara or in Correggio, but it is certain that an important wing of Antonio’s large workshop had moved here in force.

Observations on the architectural partitions of the great marble apparatus show a firm external trilithic setting, where the long pilasters that are kept within the canonical proportion of 1 to 7.5 rest on pedestals of restrained momentum and on perfectly connected basic plinths. The dadoes flaunt in relief the ancient Roman eagles, as perfect insignia of the local fiefdom’s belonging to the lands of the Empire: at present they are rather abraded, but in his visits Charles V must have laid his eyes on them with real pleasure. The pilasters support elegant capitals where the Corinthian model is restrained in a flat Renaissance version. Thus, evoking the two “Scuole grandi” of St. John’s and St. Mark’s in Venice - both Lombardesque in the late 15th century - and also the interior facades of the Ducal Palace, here too in Correggio the exterior members of a finely pictorial character offer sculpture fields of sliding and specially designed preciousness that appear entirely connatural and ingemmant, that is, predetermined elements of the entire design.

The solemn entablature is all about the sculpted frieze, contained within the very fine beaded architrave and the light, ovulated and foliated cornice above.

The west facade of the Princes’ Palace receives the full sun from the noontide, in the early hours of which the caressing light enhances the half-relief modeling of the long ornaments, the thickness of which is also calculated on architectural dimensions. The prominence of the forms at times thrusts toward a virtual tuttotondo, and at times settles into the details like a stiacciato of accurate detail: a living richness then, which never tires us.

The general layout of the sculptural apparatus follows distinct parts. The two internal pilasters, supporting the arch, make their decorative elements rise from virtually bronze bases, barely raised, and proceed vertically: they thus become two splendid candelabras placed on either side of the entrance as signs of utmost honor to the incoming guests; at the impost of the archivolt they are sealed by cubic capitals, simple and pearl-bearing, and the upper, semicircular band flaunts a festive sequence of plant festoons and cups, unbroken by any keystone. The spirited decoration totally prevails, by way of coronation for the acceding nobles. The outer membranes, above the eagles at the dice that closely resemble those on the Ferrara pillars of San Cristoforo at Certosa, start their figurative discourse from above: a knotted cord at a flower, complete with ribbons, holds down an astonishing series of heraldic feats and declarative initials, all tied in succession. Before dealing with the overall anthology of sculptural terms, it is good to observe the extensive frieze of the entablature where the coat of arms of the noble house of Da Correggio with its horizontal bands stands out in the center, but without the imperial intertiate and the coat of arms of the Brandenburgs, as will happen immediately afterwards in the painted frieze of the Sala del Camino (1508).

Nicolas II’s theatrical culture constantly surfaces in the design of the Portal, and the Count of Correggio foresaw distinguished visitors not only for nobility of lineage but also for lofty intellectual gifts. Indeed, the Court Palace then welcomed such personages as the Dukes of Ferrara, the Marquis d’Avalos, Emperor Charles V, cardinals and bishops, and on the other hand - guests of Veronica Gàmbara - Ludovico Ariosto, Bernardo and Torquato Tasso, Pietro Aretino, musicians and artists. The various realizations of significant furnishings of the noble palaces were at that time memorized in written reports and sent from court to court: therefore, their projects were very studied both for general significance and in the many details, often surprising and decipherable to the learned. Isabella in Mantua was a text!

Let us now come to the iconographic and semantic richness of the four emblematic sequences that form the most sonorous and solemn canticle of this Portal: the two candelabras and the two pendants. We must state at once that in the vast Renaissance area of the Adriatic slope what we might call the “lectionary of ornate symbols in sculpture” is present, besides in the Venice of the Lombardos - who appear to be its most copious sources - also in Bologna (the Porta Giulia of the Palazzo Comunale, 1506), in Urbino (the Cappella del Perdono and the door jambs of the piano nobile), in other cities and most notably in Ferrara where some tópoi are found in the Palazzo Costabili and in several monuments of the Addizione. In Correggio, therefore, we start with a multiple and almost perturbing presence: at the height of the visitor’s face and hands, four glabrous and spirited faces cry out with loud mouths; two stand in the inner pillars and two in the outer ones. They would be called exaggerated Erinyes: the two outer ones disheveled and winged; the two inner ones shaggyly radiate and crowned with a violent foliate cast. Given the general amiability of the whole figurative apparatus they should have only a powerful apotropaic function: the host was thus immunized from all negative possibilities and insured from all possible ills.

The two inner candelabras proceed nobly by arranging cups, torches, and eagles, and find an exculpatory term of theatrical character in the triad "càntaro or crater - mascherone - eagle with open wings." On the masks, also horned, which we find four times in the Portal, we can recall their ancient theatrical use, but their more recent genesis comes from Romanesque sculpture where modern critics call them green men (woodland apparitions) but which must be better interpreted as “bystander spirits,” inspirers and protectors of undertakings (two in fact stand within a crown). The sequences of the outer pilasters are larger in size and are totally framed by a ring of “flower-like” worked orbicles with the constant and very precise use of small holes executed “violin-like” (the sculptors’ string drill), which becomes a most pleasing ornament. These two pendant registers contain at a proper height the arrowed plaques with the large, engraved and leaded words, AMICIS 7 FIDEI. This is the declaration of sodal friendship toward allies and welcome guests, and of assured fidelity in the imperial sphere. The scrolling of symbols, from the top down to the assured cry of the Furies, is of a broad, dilated warlike character, interrupted only by the tasty fruits of an ideal victory. These are white weapons and helmets, the characters of which are not at all of battle, but of festive pageantry, of great occasions and receptions, as was the custom at the Courts on special occasions. “Animated” helmets, equipped with wings and desinent in zoomorphic figurations are such as to arouse exciting thoughts, such as dragons or insidious animals. Leonardo lent himself to these transfigurations at the court of Milan, driven there above all, in our opinion, by that great theatricalist who was Nicolò II da Correggio, director of every event or carnival. And that Nicolò transported its examples and atmosphere, with the help of an excellent Lombard master, into “his” Portal there can be no doubt. This masterpiece remains as the highest example of sculptural-decorative proclamation in the Adriatic area and in the first decade of the Italian sixteenth century.

Nicolò for the Palazzo di Correggio also took care of the capitals, the vere da pozzo, and the cantonarie, but he was especially committed to the Porta Magna, the one that at the top of the staircase gave access to the Salone d’onore, all frescoed, and to the Sale di rappresentanza, also furnished with elaborate ceilings and painted bands manifesting special vocations, such as music. The Porta Magna, not much respected over the centuries, will have to undergo a special study starting with its very material, which - for now - seems to be strong stucco. Of it we are interested in the primitive form and the very unique molded frieze. The closing invitation is therefore a trip to Correggio, with illuminating disputes.

Bruno Zevi, Biagio Rossetti, ferrarese architect, Ed. Giulio Einaudi, Turin 1960

G. Adani, A. Ghidini, F. Manenti Valli, Il Palazzo dei Principi in Correggio, Ed. ACRI (Amilcare Pizzi), 1976

Matteo Ceriana (ed.), The Alabaster Camerino. Antonio Lombardo and antique sculpture, Silvana Editoriale, 2004

A. Guerra, M.M. Morresi, R. Schofield (eds.), The Lombardos. Architecture and sculpture in Venice, Marsilio, 2006

Special thanks to our friend Giancarlo Garuti, author of valuable photographic footage.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.