Over the course of his career Perugino (Pietro Vannucci; Città della Pieve, c. 1450 - Fontignano, 1523) made several gonfalons, or banners that were usually painted on canvas because they were intended to be carried during processions, and thus had to be relatively light. The term gonfalon derives from the Old French gonfalon, a dissimilated form of gonfanon that is traced back to the hypothetical voice fràncone (a family of West Germanic dialects) gundfano, properly a banner of war (German Fahne: flag). Probably therefore originally related to the world of war, the banner later took on a different value, as a municipal symbol, of associations, confraternities and religious companies, becoming a symbol of belonging and identity. It was precisely a generally rectangular banner, supported by a horizontal pole mounted on a vertical one, so as to keep it outstretched.

Among these gonfalons made by Perugino is the Gonfalone della Pietà, better known as the Gonfalone del Farneto, which is now part of the collections of the National Gallery of Umbria in Perugia. The latter was restored on the occasion of the major exhibition The Best Master of Italy. Perugino in his time, with which the museum aimed to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the Umbrian master’s death .

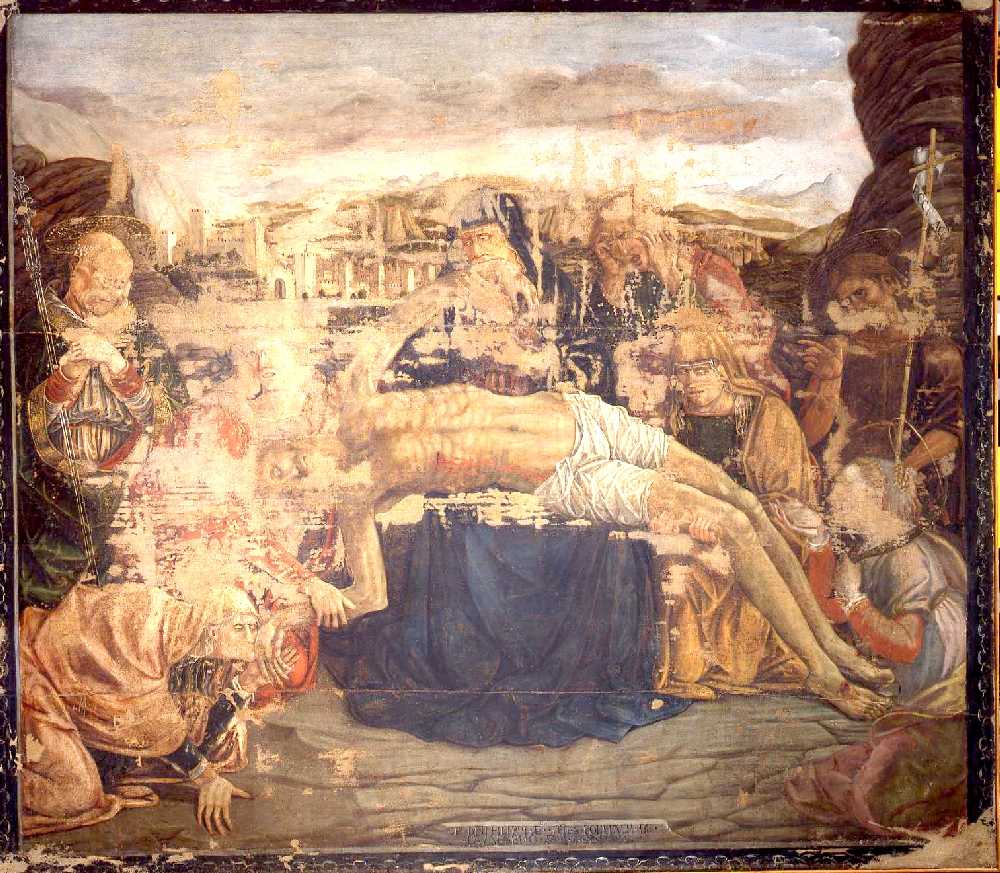

Its name links it to its provenance, namely the Franciscan convent of the Santissima Pietà del Farneto in Colombella, on the road between Gubbio and Perugia, and here it remained until the mid-19th century, placed on the right wall of the church. The Gonfalone del Farneto, a processional banner originally used for Lenten processions, was made in tempera on canvas around 1472 and is, even according to critics, one of the masterpieces of the artist’s early production . It is an unusual fact that the work is executed on canvas (a circumstance that has led to its being considered, precisely, a gonfalon), a medium that was not very common at the time, and what is more, it was made with a particular technique. The latter is unusual: “it differs, in fact, from the more common paintings on canvas of the second half of the 15th century, as Perugino will also do,” explains scholar Veruska Picchiarelli, “because it lacks the preparation layer between the support and the paint film. The binder used appears to be a tempera grassa, with oil mixed with egg or animal glue. This combination, which resulted in the penetration of the color into the plant fiber, is responsible for the earthy and opaque appearance of the material, which probably did not even receive a final varnish originally, as diagnostic investigations suggest. Another singular aspect in the technique is represented by the very conspicuous stitching that joins the two canvas flaps of the support in the central part. The lack of the shock-absorbing layer represented by the preparation accentuates the evidence of the joint, but such ’neglect’ in a painting otherwise caressed in the smallest details leads one to imagine that the humble and humble appearance was intended and sought after, perhaps for devotional needs.”

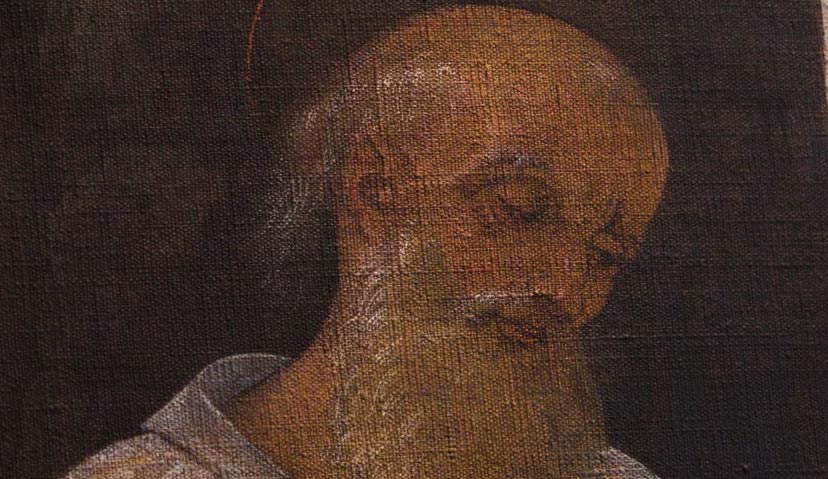

In the work, among the most important and significant of the period, elements traceable to the lesson of Andrea del Verrocchio can be recognized: during his Florentine sojourn, Perugino in fact frequented his workshop, considered the most important and most fruitful in Medici Florence; to give an idea, great artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Sandro Botticelli, and Domenico Ghirlandaio, who became as we know geniuses and masters of art history, passed through and were trained here. Perugino was able to reread Verrocchio’s lesson, particularly the latter’s naturalism , through a profound lyricism: a combination of Perugino’s most characteristic trait and the master’s teachings that is most clearly visible in the painting, especially in the earthy colors with which the work is imbued, in the almost milky tones of the robes of the side characters, on which light seems to refract as if they were metal foils, and in the rendering of volumes and anatomies, with marked and somewhat angular strokes (note also the almost skeletal body of Christ). Theearthy and opaque appearance of the subject matter, which characterizes the painting, is given by the combination of a binder, probably an oily tempera, with oil mixed with egg or animal glue, thus entailing the penetration of the color into the plant fiber, and by the absence of the preparation layer between the support and the paint film. An unusual technique that differs from the more common canvas paintings of the later 15th century.

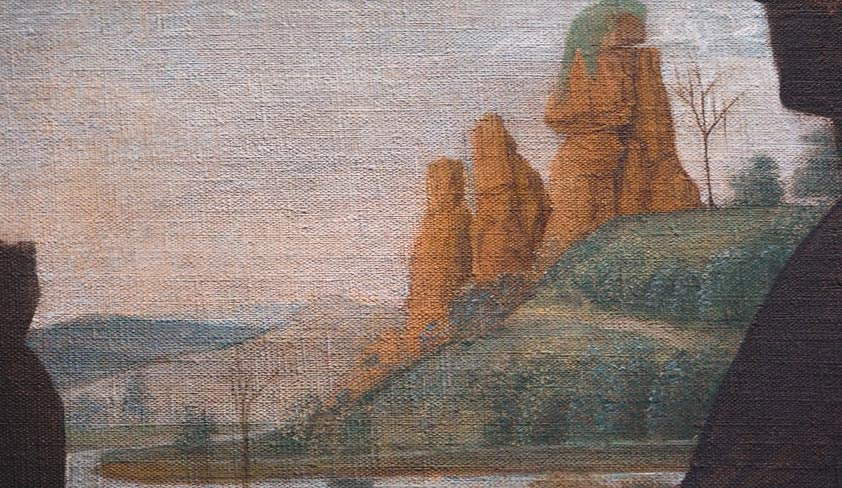

Also of primary importance is the light that comes from the left, creeping through the folds of the robes like shining mirrors; it illuminates the eyes of the lion crouching next to St. Jerome, the haloes that become discs of reflective metal, and the golden clasp with the seraphim that clasps the Virgin’s mantle to her breast. Note the contrast between the backlit rock face on the left and the completely sunlit rock face on the right, suggesting the setting of the scene in a shadowy gorge, which becomes open behind the figures in the foreground. The edges of the nimbuses also show bright highlights, ranging from yellow through orange to violet. There is also great expressiveness in the faces of the characters depicted, especially in the Virgin (her face is furrowed with folds drawn by despair and tears) and Magdalene, who express deep drama, further represented by the gesture of the latter’s hands. The rocky landscape, reminiscent of the Flemish Quattrocento, lends an intimate and meditative note to the whole work, in keeping with the commissioning of the Franciscan friars, who in the convent of the Santissima Pietà del Farneto, located on a rise surrounded by a forest of farnie, a kind of oak tree, were to recall the experience of ancient hermits in the desert. It is no coincidence that one of the characters depicted in the work is precisely St. Jerome, kneeling in prayer and accompanied by the lion: his presence harks back to one of the most famous episodes in the life of the saint who, attracted to the ascetic life, during his time as a hermit in the desert, encountered a lion with a thorn stuck in one of its paws; the saint removed the thorn, healed his paw, and the animal, eternally grateful to him, from that moment on never abandoned him, remaining faithful to him. Saint Mary Magdalene, too, although depicted with more drama, is on her knees, in a position of penitence.

Between the two penitent saints, in the center of the painting, the artist has depicted Our Lady, dressed in a long dark brown dress that falls broadly to the ground in stiff lines, forming edges; her face is visibly distraught with grief at the death of her son. She holds him lying on her lap, supporting him with her right hand under his head and with her left hand, forcefully, by one thigh so that Christ’s body does not slide forward. His body, deadweight, rendered even by his left arm hanging down touching his mother’s robe, is covered only by a narrow drape encircling his hips, and thin rivulets of blood still flow from the wound on his side. The face has drawn features, but not as dramatic as the Madonna’s: in fact, she appears to be just sleeping. Still on the subject of the characters, as the scholar Emanuele Zappasodi (for whom the Pietà del Farneto should be regarded as one of the cornerstones of the young Perugino) writes, here "entirely new for Perugia is the relationship between the characters in the foreground and the wide landscape behind them, and completely unusual also is the insistent tour de force with which the lights are minutely investigated. The light spills in from the left, creeps between the reeded folds of the robes, casts the long shadow of the metal ciborium on the ground, soaks the tears, even bathes the eyes of the lion crouching in the half-light, flashes on Magdalene’s jewels and sparkles on the thicknesses of the nimbuses, veritable mirror disks as in Piero della Francesca’s Perugia polyptych and as in Florence in the works of Andrea del Castagno and Alesso Baldovinetti."

The subject of the Gonfalone is thus the Lamentation over the body of Christ, that is, the moment following the deposition from the cross: a Pieta in which Saint Jerome and Saint Mary Magdalene attend and participate on either side. However, the composition is inspired by the scheme of the Vesperbild, a German term that literally means “image of the Vespers” and indicates a genre of sculpture that originated in 14th-century Germany made from poor materials, mainly painted wood, depicting the Pieta, that is, the seated Madonna holding on her legs the lifeless body of Jesus, just laid down. The aim of the Vesperbilder was precisely to create in the viewer, or rather in the faithful, a feeling of compassion for the suffering experienced by Mary and the saints around her, and thus of participation in the pain. According to this compositional scheme, the Virgin is the apex of a triangular composition with the two penitent saints in the corners at the base; the latter are also smaller in size than the larger Virgin-Christ group to emphasize thehierarchical order, the most important figures in the painting.

Based on the model of the Farneto Gonfalone, the now elderly Giovanni Boccati made the gonfalone with the Pieta and saints: it too is a processional banner, but its provenance is uncertain. Boccati’s Pietà , made in 1479, although it has some similarities in composition with Perugino’s Gonfalone, it does not achieve the sophisticated language of the Farneto Pietà. Boccati also populates the scene with many characters, giving the work a tone of choral tragedy. He, too, however, places the Madonna with the outstretched body of Christ on her knees in the center, and on the sides of the painting he uses rocks as if they were wings. Both paintings thus testify to the spread in Umbria of the Vesperbild iconography, which probably arrived here through the stone and plaster sculptural groups made by German artists and their Italian followers present in the region during the 15th century. In the background, however, Perugino proposes a landscape characterized by rolling hills, his typical thin-stemmed saplings, and a body of water, probably reminiscent of the Umbrian landscape, to which he adds tall rocks.

The theme would be taken up again by the artist in the late 15th century, between 1493 and 1496, in the Pietà now in the Uffizi: here the rocky landscape and rocky backdrops disappear to make way for a monumental Renaissance portico with pietra serena pillars, which becomes a dividing element between the hilly landscape in the background and the characters all depicted in the foreground. Made for the church of the Ingesuati of San Giusto alle Mura in Florence, again Perugino places the seated Madonna at the center of the scene with the body of Christ lying on her legs, no longer skeletal as in the Gonfalone del Farneto. On the sides, on the left, kneeling St. John the Evangelist holds the torso of Jesus with a lost and at the same time afflicted air, while standing is a young man, perhaps identifiable with Nicodemus; on the right, Mary Magdalene seated in the act of prayer with her head bowed and on her knees the legs of Christ, while standing is Joseph of Arimathea. Unlike the early works of the 1570s, here the colors turn from earthy to bright and vivid, the lines more delicate and rounded, and although an intimate and meditative atmosphere remains, the faces of the characters are much less marked by dramatic expressions and features. There is in fact a greater composure and refinement.

Perugino,

Perugino,The Pietà made by Perugino himself and now housed in the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin is also of a similar setting. Datable to about 1495, this work also depicts Lamentation over the Dead Christ, with the seated Madonna in the center holding the dead body of her son on her knees, holding him with her right hand under the nape of his neck, while her left hand rests on one thigh. Positioned symmetrically on either side of the Madonna stand, on the left St. John the Evangelist looking toward the viewer with Christ’s head resting on his shoulder, and standing Nicodemus looks up to heaven holding his hands together in prayer; on the right St. Mary Magdalene holds Jesus’ legs on her knees, and standing Joseph of Arimathea watches the scene moved.

It all takes place under a loggia with round arches supported by pillars, and above the capitals can be glimpsed the coat of arms of Charles Gouffier, the painting’s first owner and a courtier of Francis I. In the background is the characteristic Umbrian hill landscape dotted with almost stylized saplings, and some tiny figures are also seen at the site of the Crucifixion. As in the Uffizi Pietà, the patheticism and drama that characterized the Farneto Gonfalone has markedly diminished, the atmosphere seems more serene, and the colors have also become more pastel, thus overcoming the earthy hues of the latter. The work is signed “Petrus Perusinus Pinxit,” in gold letters, on the small wall behind the Madonna, below Christ’s elbow. A theme, that of the Lamentation over the Body of Christ, which is tackled by Perugino several times and which, as we have seen, was depicted with a different approach twenty years apart between the Gonfalone del Farneto of the 1570s and the later Pietà of the Uffizi and Dublin in the 1590s.

The article is written as part of “Pills of Perugino,” a project that is part of the initiatives for the dissemination and diffusion of knowledge of the figure and work of Perugino selected by the Promoting Committee of the celebrations for the fifth centenary of the death of the painter Pietro Vannucci known as “il Perugino,” established in 2022 by the Ministry of Culture. The project, edited by the editorial staff of Finestre Sull’Arte, is co-financed with funds made available to the Committee by the Ministry.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.