"For Game is too much, for war is too little ." With these words, in 1807, Marie Louise, Queen Regent of Etruria, put an end to the Gioco del Ponte in Pisa, only one edition of which was contested throughout the 19th century. The event resumed in the 20th century and with continuity since the postwar period: the Gioco del Ponte is in fact one of the most heartfelt events of the Pisan tradition, capable of mixing history, folklore, and civic pride, and is rightly included in that group of events, poised between historical re-enactments and competitions that are still alive, which in Tuscany still have great fortune and following, such as the very famous Palio of Siena, the Florentine Calcio storico, or the Giostra del Saracino in Arezzo. Every last Saturday in June, the city of Pisa is filled with the colors and flags of the participants, and visitors flock to the city, who with bated breath follow the famous clash that takes place on the Ponte di Mezzo bridge over the Arno and stands as the main link between the two sides of the city.

The traditions of the Game are very old: it is commonly believed to be the heir to the Mazzascudo, a kind of medieval tournament that took place during the splendors of the Pisan Republic in Piazza degli Anziani, today’s Piazza dei Cavalieri. The intention of this tournament, like others, was to make war a game, keeping participants in training to be more ready on the battlefields. Mazzascudo consisted first of individual challenges then between factions, the Rooster and the Magpie, who fought each other to the sound of clubs and shields over opposing playing territory. Apparently, the first records of such a challenge date back to 1168, and it was long-lived, at least until the beginning of Florentine rule in the early 15th century.

It was from these premises that in 1568 under Grand Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici that the new game was devised; the Ponte Vecchio (now known as the Ponte di Mezzo) was the chosen setting, and the opposing factions contested the two banks through physical combat using the “targone”, an elongated wooden board resembling a mace, used as much to offend as to defend, and bearing the colors of the different teams, made up of players from the two sides of the city, Tramontana to the north and Mezzogiorno to the south, and divided into teams of 50 or 60 soldiers. The combatants dressed in clothing of the time or in some editions in fancy robes, with references to the exotic or military exploits against the Muslims. With this set-up, although the rules were changed several times, the Game prospered until the advent of Peter Leopold of Lorraine, to whom it was disliked because it involved unrest and autonomist reminiscences, and was suspended for twenty-two years. In 1807 it was finally suppressed because it was considered too bloody.

It took until 1935 for it to be reinstated by fitting into the Fascist policy of greening up ancient local traditions, but only three editions were able to be played before the World War interrupted its holding again. In the Post-War period the event was resumed almost immediately, but editions alternated without regularity, which could only be found again in the 1980s. The physical clash was replaced by a contest, with the parties pushing a mechanical wagon, attempting to steal ground from their opponent. This solution came about to avert the risk of accidents caused by physical contact between men.

The Gioco del Ponte has entered with such pervasiveness into Pisan life and traditions that there is a rich iconographic production that has the celebrated historical re-enactment as its subject: a production that allows, through paintings and prints, to relive the splendor of the event, in all those aspects that have been lost or have inevitably changed over time.

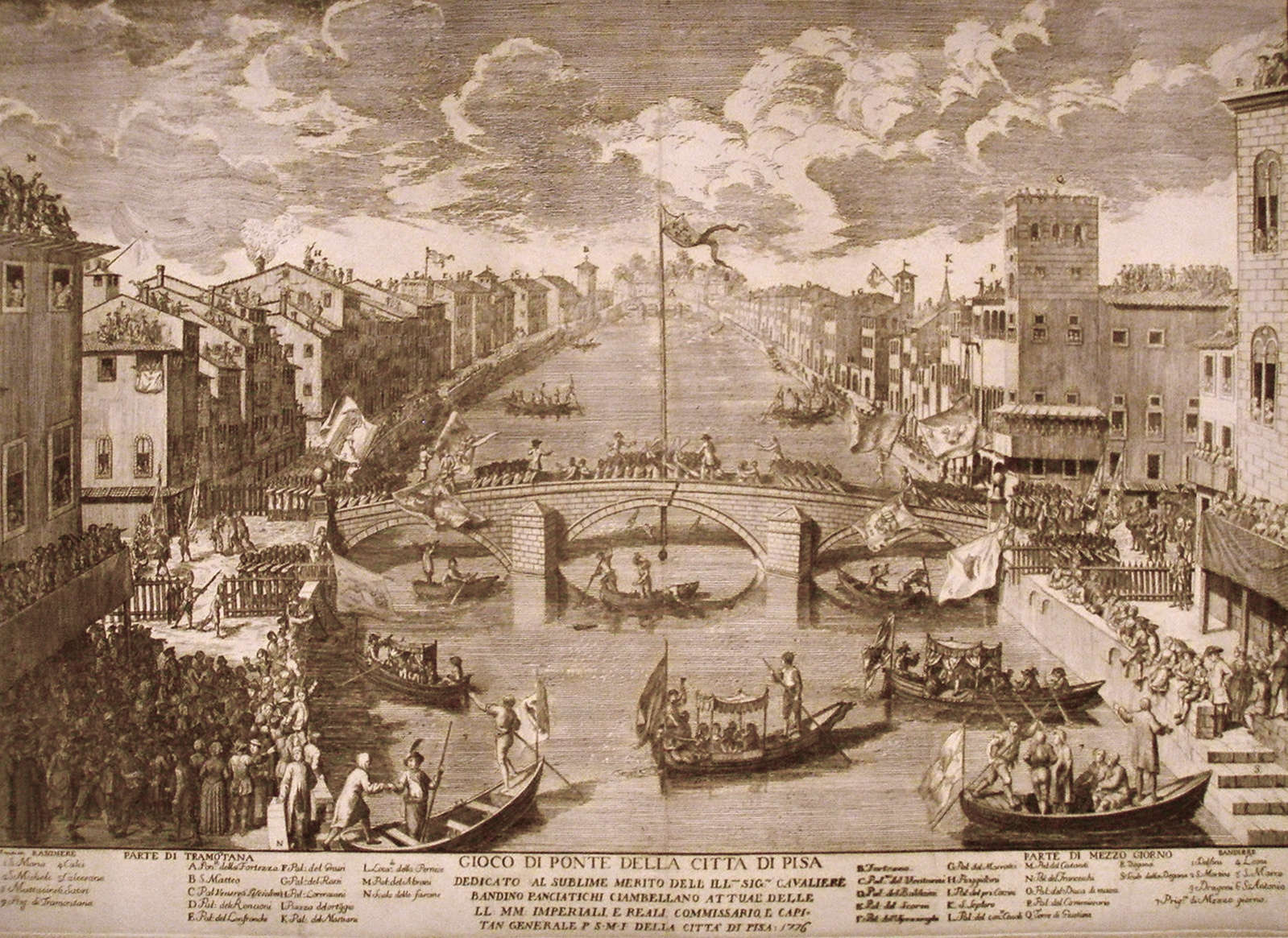

In particular, engravings were made to accompany publications and booklets that had the Gioco del Ponte as their subject, sometimes accompanying poetic compositions aimed at magnifying the victory or courage of the individual teams, or realizations designed as stand-alone objects. Countless are the sonnets, madrigals, canzonettas and disfida signs that accompanied the various editions of the Game over the centuries; although many of these sheets have been lost, a relevant quantity has been collected and is preserved in the University Library of Pisa. Of these we note a few that are accompanied by illustrations depicting the Gioco del Ponte: The sheet entitled On the occasion of awakening the noble and delightful emulation of the bridge game in the city of Pisa dates back to 1785, where in the lower part a group of flag-wavers is represented, while at the top the Bridge is seen with the challenge in progress, the Judges, the two “Forts” on each side and the teams in war gear, below the bridge sail some boats waiting to render aid to the unfortunate, who in the heat of the battle might unfortunate fall, as moreover happens to some targoni in the illustration. Also dated to the same year is the Pisa Giuliva sheet for the Explanation of the Twelve Flags of the Giuoco del Ponte [...] in which this time the counterpart print shows the bridge and a section of the lungarni unfolding on the sides, with the Palazzo Pretorio towering on the left, while the motif of the targoni plunging into the water is taken up.

Among the oldest and most interesting prints devoted to the theme, mention should be made of an etching from 1608 entitled Il nobil antico giuoco del combattimento del ponte solito farsi a Pisa [...] signed by Matthäus Greuter, an engraver originally from Strasbourg, also known for having edited the iconography of Galileo Galilei’s text Istoria e dimostrazioni intorno alle macchie solari. It illustrates the 1608 edition of the game, which was played in Florence on the Santa Trinita bridge at the behest of Grand Duchess Christina of Lorraine and was included in the wedding celebration program of the princes of Tuscany Cosimo II and Maria Magdalena of Austria. It was the grand duchess herself who armed two squads at her own expense and ordered the Knights of St. Stephen to make up two more.

As scholar Laura Zampieri already noted, the illustration presents the Exhibition of Arms, or historical parade, where characters in unusual costumes for the Game also appear: Persian, Roman and ancient Greek garb, Moors and Cyclops for the Tramontana side; Swiss, Turks, Lusitanians and Indians for the Mezzogiorno side, demonstrating how that year’s edition had a connotation closer to the Medici taste than to the traditional one. In the image, the procession occupies both the banks of the lungarni as well as the bridge, while a river island is located in the Arno where the Marzocco, the lion symbol of Florence, and a river deity modeled after the Marforio statue in Rome have taken their place. The same engraving was also reused in the following century, with minor variations, but purging it of the 57 figurines that make up the Exhibition.

Another famous print is by Anton Francesco Lucini and the well-known engraver Stefano Della Bella, of which three states are known, the first of which dates from 1634. The view seems to emphasize more the environmental and architectural context of the scene than the unfolding of the Game: in fact, the embankments with the palaces, and in particular the left bank that occupies part of the foreground, are accurately described, with the meticulous narration of bystanders in seventeenth-century clothing, horses and carriages. The bend in the river is enlivened by galleons, while a few small boats are stationed under the bridge, where they await the fall of a fighter who in the rush of play is slipping into the water. This engraving also takes on the role of a valuable iconographic testimony by showing how the old bridge looked before it collapsed in 1637.

From the middle of the following century, more precisely from 1761, is the beautiful etching attributed to Gaetano Franchi, accompanied by a caption, which makes it possible to identify the best-known palaces and monuments that insist on the embankments. In this one, the fences containing the combatants are noted and the great contest of visitors crowding along the banks and over the roofs of the palaces stands out, while the battle rages on the bridge where, although forbidden by the rules, some participant is irregularly using the targone as a club to strike his enemies. The violence of the clash is reiterated by the usual and constant motif of the targons plunging into the Arno. This print served as a model followed almost slavishly by the engravers who rendered the Game of the Bridge in later decades.

The graphics, in themselves very valid evidence for reconstructing the appearance and organization that the Gioco del Ponte had taken on in the course of past editions, have the limitation of being all in black and white and of not instead restoring the bright polychromy of the costumes, flags and insignia, which instead was a fundamental component of this event. Fortunately, some paintings found in Florence come to our rescue: an oil on canvas by an anonymous artist and dating back to the 17th century that is housed in the Stibbert Museum and two works belonging to the collections of the Palatine Gallery in Palazzo Pitti. In particular, the latter are works of no great quality and in a mediocre state of preservation, but the divergences they show in composition are a cause for interest. A canvas rather dark in color rendering is attributed to Gherardo Poli, where the artist’s interest seems to be distracted from the game itself in favor of the crowd, whose components achieve a pictorial quality that is certainly not repeated in the uncertain architecture, so much so that the painter takes creative license by enlarging the stretch of the lungarno in the foreground to increase the terrain trampled by the throng, in a partially distorted perspective. While it seems to depend directly on Della Bella’s engraving the other Florentine canvas, whose solution repeats the lungarno on the left in the foreground, trampled by numerous onlookers as well as a carriage. It deviates from the model, however, not only because of an unreliable perspective, but also because of the inclusion on the bridge of the antenna with the Pisan banner, which is absent in the etching, since it began to be in use in the Game only from 1662, after the bridge was rebuilt.

Of quite a different quality are the works, perhaps the finest dedicated to the theme, by Giuseppe Maria Terreni, a painter and engraver from Livorno, whose services, particularly in the fresco technique, were long in demand by the grand ducal court. Terreni produced four tempera paintings commissioned by the grand duchy on the occasion of the May 1785 edition, contested during the visit to Tuscany of the royals of Naples, Ferdinand III of Bourbon and his consort. The works illustrate moments of the festivities, and two of them are related to the game. These are Veduta con campamento delle truppe destinate al gioco del ponte nella piazza del duomo a Pisa and Veduta della Vittoria nel Giuoco del Ponte a Pisa riportato dalla parte di Sant’Antonio, in which the tradition of the event is celebrated with mundane and courtly vivacity amid persuasive colors, which transform the competition from a violent clash to an elegant celebration.

A recurring element in all illustrations dedicated to the Game is the ubiquitous turnout of the public, demonstrating how in previous centuries up to the present day, the Gioco del Ponte is one of the most anticipated events in the city of Pisa.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.