by Federico Giannini, Ilaria Baratta , published on 22/01/2021

Categories: Works and artists

/ Disclaimer

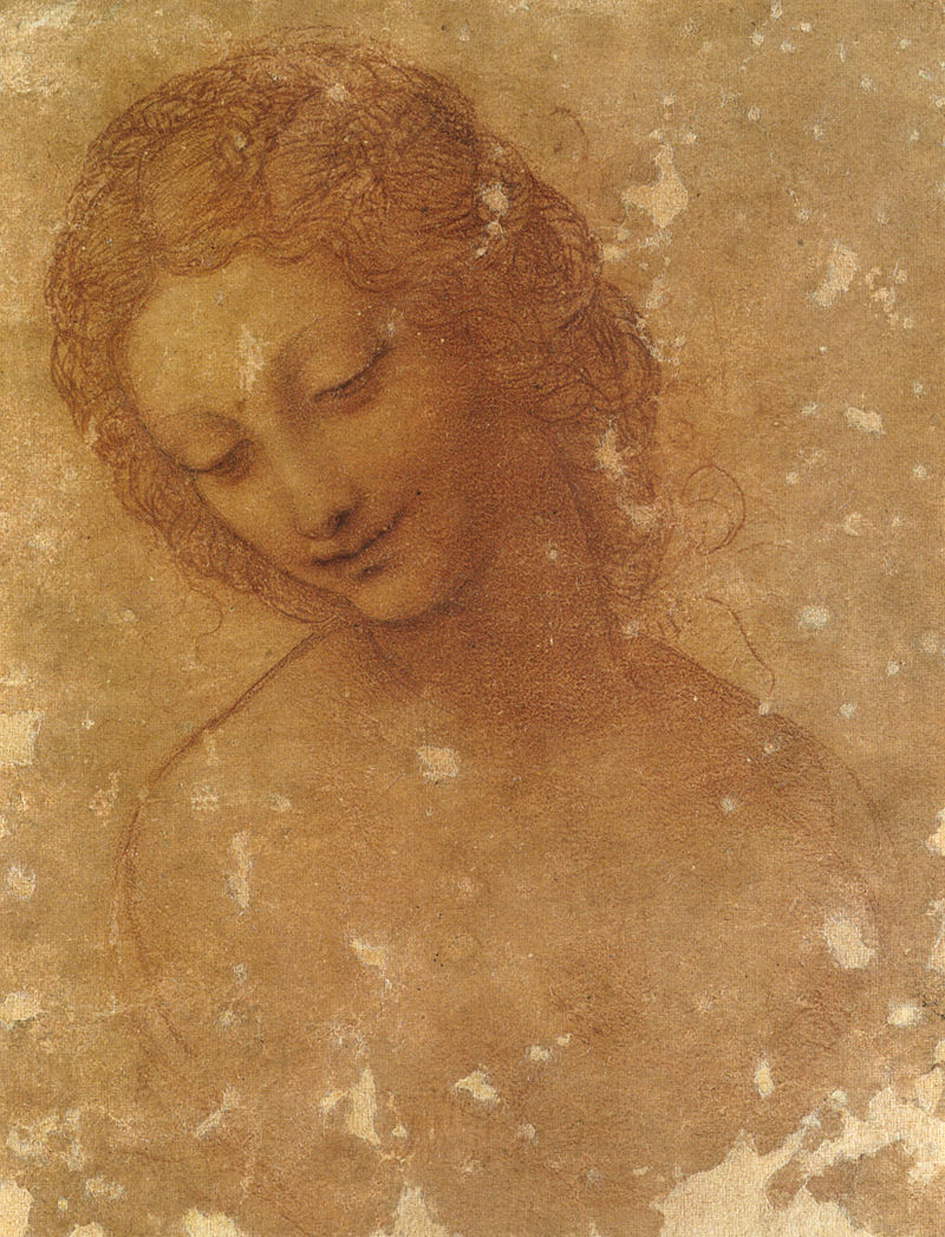

Leonardo da Vinci's La Scapigliata, preserved at the National Gallery in Parma, is one of the best-known works by the great Tuscan artist. At the center of a very long attributive debate, the work is one of the symbols of female beauty in Leonardo.

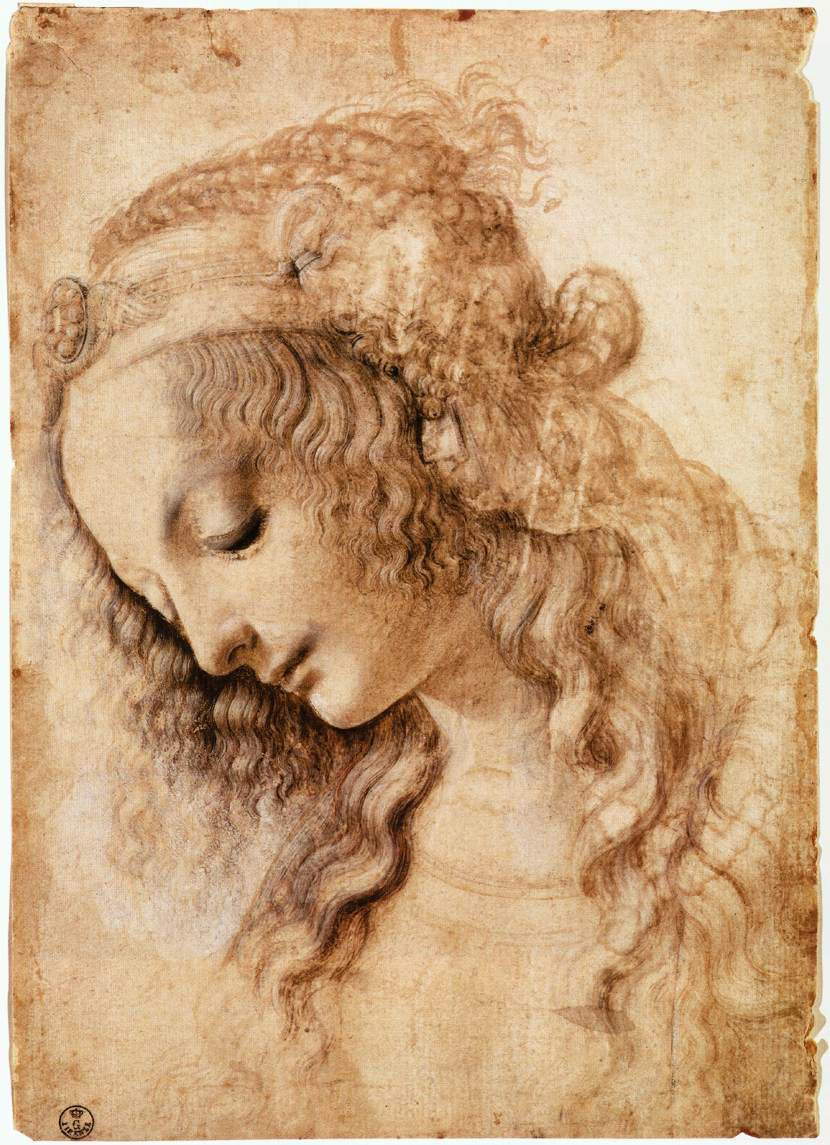

“Fa tu adonque alle teste li capegli scherzare insieme col finto vento intorno alli giovanili volti”: thus, in a passage from his Treatise on Painting, datable to 1490-1492, the great Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452 - Amboise, 1519) suggests, to the painter who intends to learn the secrets of art, the way in which to execute the hair of the subject depicted. It comes almost naturally to associate this piece with perhaps one of the best-known works of the Tuscan genius, namely the Scapigliata (or Scapiliata) now in the National Gallery in Parma. It is a painting done in white lead with iron pigments and cinnabar on a walnut panel: the subject is a young woman, depicted with her face three-quarter facing downward, her hair tousled (hence the name by which the work is universally known), her eyes half-closed, her expression gently melancholy, all left in a state of conspicuous unfinishedness. It is a small tablet, moreover resected and trimmed along the right edge, probably because at some unspecified time in history it was intended to fit into a frame. But its history is still largely unwritten.

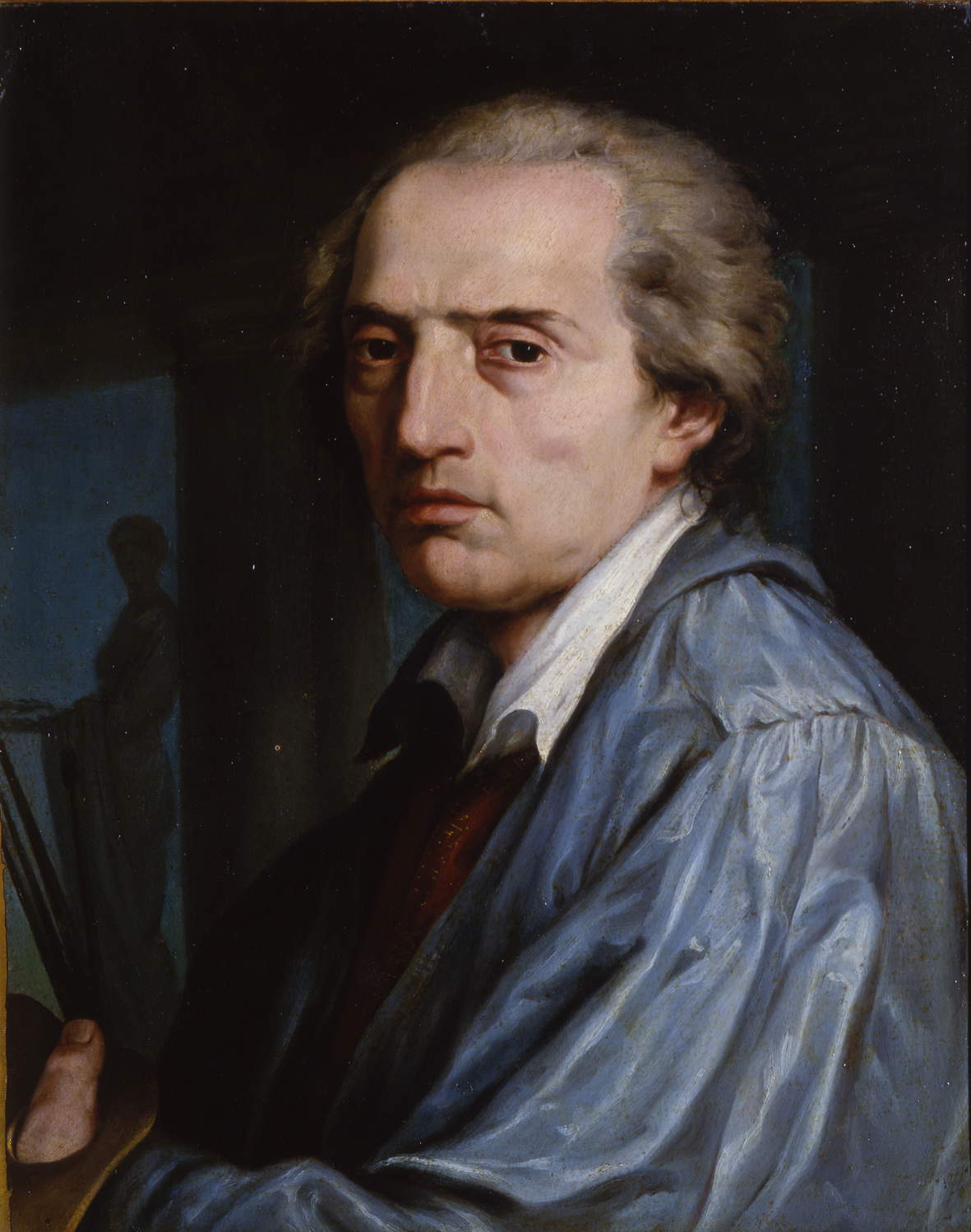

Indeed, in the documents, there are no sources contemporary with Leonardo that specifically mention it. The term “Scapiliata” appears for the first time in theinventory of Duke Ferdinando Gonzaga’s possessions (drawn up between January 12 and March 3, 1627 and now preserved in the State Archives of Mantua), where it mentions “a picture painted with a head of a scapiliata dona, bozzata, with violin frames, oppera by Lonardo d’Avinci, estimated at 180 lire.” It is not certain that this is indeed the Scapigliata now in Parma, but many wanted to associate this inventory mention with the small painting. The known history of the work begins only in 1826, when the heirs of the painter Gaetano Callani (Parma, 1736 - 1809) offered the Scapigliata to the Academy of Fine Arts in Parma, where, however, it would not eventually enter, because it would be the Galleria Palatina that would receive the panel, in 1839, with attribution to Leonardo da Vinci.

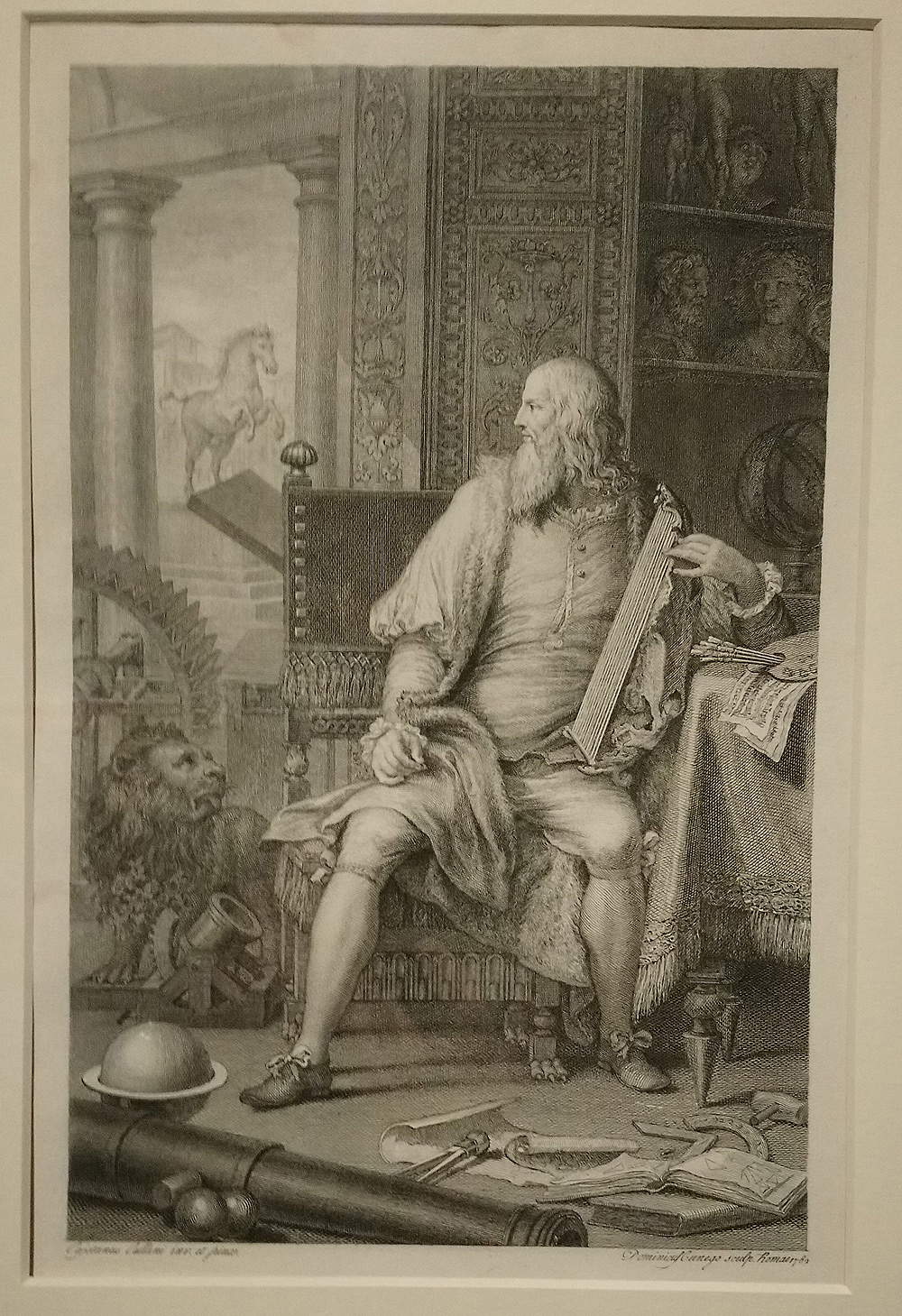

And it is precisely the figure of Callani who established a strong link between Leonardo da Vinci and Parma. Callani, in fact, manifested a strong interest in the great Renaissance artist: the Complesso della Pilotta preserves a drawing of his depicting Leonardo da Vinci in his studio (from which the Veronese Domenico Cunego later drew an etching in 1782) that represents perhaps the most vivid testimony that the Parma artist nurtured for Leonardo da Vinci. Some of the tools surrounding Leonardo in Callani’s drawing, moreover, infer Callani’s own knowledge of the Codex Atlanticus, which the artist had evidently known through the copies his brother-in-law, Carlo Giuseppe Gerli, had made of it, publishing them in a printed edition in 1784. Carlo Giuseppe Gerli and his brother Agostino developed a real passion for Leonardo’s work, to the point of even building some devices based on Leonardo’s models: scholar Alberto Crispo has speculated that the two brothers probably played a role in Callani’s purchase of the Scapiliata. But that’s not all: in a 1780 letter sent to an interlocutor who is not known to us, Callani thought of involving the Academy of Fine Arts of Parma in a negotiation to bring to the city a painting by Leonardo with the Madonna, Child and St. John (presumably the Virgin of the Rocks, now at the National Gallery in London, and at the time in the possession of a private individual): the negotiation unfortunately failed, and otherwise today Parma would have been able to boast of exhibiting another of Leonardo’s most renowned masterpieces. It remains a fact that the figure of Callani, Crispo himself wrote, proved “fundamental for the development of studies on Correggio and Leonardo in the second half of the 18th century and for the role he played, not only in Parma, in the art market and collecting.”

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Head of a Woman known as La Scapiliata (c. 1492 - 1501; white lead with iron and cinnabar pigments, on white lead preparation containing copper, lead yellow and tin pigments on walnut panel, 24.7 x 21 cm; Parma, Complesso Monumentale della Pilotta, Galleria Nazionale) |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, The Scapiliata |

|

| Maria Callani, Portrait of her father Gaetano Callani (1802; oil on panel, 49 x 40 cm; Parma, Complesso Monumentale della Pilotta, Galleria Nazionale) |

|

| Domenico Cunego, Leonardo da Vinci in his studio (1782; etching, 319 x 206 mm limpronta, 381 x 241 mm the sheet; Parma, Complesso Monumentale della Pilotta, Palatina Library, Ortalli Collection) |

|

| The setting up of the Scapigliata at the National Gallery of Parma |

|

| The setting up of the Scapigliata at the National Gallery of Parma |

Returning to the Scapigliata, as it is obvious to imagine around the tablet a debate arose that was destined to last over the years and to accompany it to the present day: it is a painting for which there are no sources from Leonardo’s time, so it seemed legitimate to some to doubt its authorship. That it was rejected, for example, by Corrado Ricci, in 1896: the great archaeologist and art historian thought that the Scapigliata was a modern forgery, and for some thirty years (before, that is, its rediscovery by Adolfo Venturi in 1924) heavily conditioned its fortunes. And in the Anglo-Saxon area, doubts about autography lasted for a long time. But there are many other art historians who instead held it and still hold it to be an autograph, especially in the Italian sphere: among others, Adolfo Venturi, Stefano Bottari, Lucia Fornari Schianchi, Eugenio Riccomini, Carlo Pedretti, Andrea Emiliani, Edoardo Villata, Pietro C. Marani. Beyond a few, albeit authoritative voices (e.g., Frank Zöllner and Martin Kemp, who have not even recently included the Scapigliata in their monographs), the attribution to Leonardo is now generally accepted.

There are many questions that this beautiful young woman raises in those who cross her gaze. Her gracefulness, the suavity of her proportions, the technical skill with which the figure is drawn, are indisputable: yet, there seems to be no trace of her in Leonardo’s writings. On what basis, then, is it possible to refer her to the master? One can start from afar: for example, from the fact that Leonardo da Vinci cultivated a certain interest in the subject of hair. When, in 1482, Leonardo left Florence to move to Milan, he drew up a list of objects and works that he most likely intended to take with him, and these works include a “head with a hairstyle” and a “head in profile with beautiful hair.” For Leonardo, hair was one of the fundamental elements of a person’s face because it constitutes a natural ornamentation of it, and for that very reason, in his view, it was necessary to avoid decorating hair or hiding it: “do not use the sliced tanning or hair of heads,” he writes again in his Treatise on Painting, “where behind the clumsy brains a single hair placed more on one side than on the other, he who holds it promises himself great infamy by believing that the surroundings abandon all their first thoughts, and only of that speak and only of that take back; and these types always have for their counselor the mirror and the comb, and the wind is their capital enemy sconciatore de gli azzimati capegli.” It thus seems clear that for Leonardo a well-composed and collected or agghindata hairstyle is artificial, far from natural: the Scapigliata, so conspicuously disheveled and with only her fluttering curls to act as a natural “ornament,” fits this idea of his well. There are also many drawings in which the artist tries to find ways to render hair on the paper: the theme becomes central when Leonardo is, for example, found painting Leda (now unfortunately known only through copies) or the Virgin of the Rocks.

|

| Leonardo’s follower, Leda and the Swan (first decade of the 16th century; oil on panel, 130 x 77.5 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci (with later resumes?), Study for the Head of Leda (c. 1504-1506; natural stone on red-pink prepared paper, 200 x 157 mm; Milan, Castello Sforzesco, Civico Gabinetto dei Disegni) |

It is interesting to introduce precisely a comparison between the Scapigliata and the angel from the version of the Virgin of the Rocks now at the National Gallery in London, first proposed by Pietro C. Marani on the occasion of the exhibition La fortuna della Scapiliata by Leonardo da Vinci, held precisely at the National Gallery in Parma, from May 18 to August 12, 2019. Marani suggests that if we take the head of the angel in the London-based Virgin of the Rocks and rotate it by thirty degrees, its figure and that of the Scapigliata become almost superimposable: moreover, we get confirmation that between the two works, the scholar says, there are “striking stylistic and even executive affinities, such as the rich and mellow material, the use of pigmented white lead, the heavy eyelids and the dark and melted pupils.” On the basis of these elements, it can also be assumed that the Scapigliata was made in the same period as the London painting, that is, roughly between 1493 and 1501 (thus a dating that anticipates that which Marani himself had proposed on the occasion of the major exhibition on Leonardo held in Milan, at the Palazzo Reale, in 2015, when the Parma panel was dated to 1504-1508). Already others (such as Adolfo Venturi and Carlo Pedretti) had suggested that there were remarkable similarities between the Parma panel and the Virgin of the Rocks: Venturi himself spoke of the “aerial quivering” of the Scapigliata’s hair, and he had approached the work (as had another scholar, Armando Ottaviano Quintavalle, shortly before him) to the London painting.

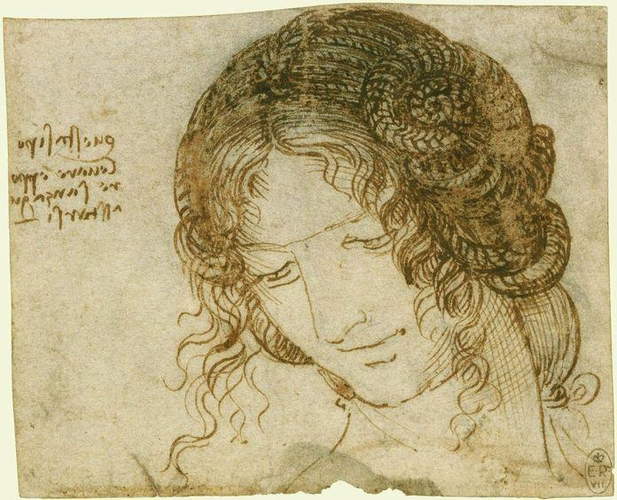

The attribution to Leonardo is thus based on stylistic data, and to find, in Leonardo’s production, works that can be compared to the Scapigliata is equivalent to embarking on a journey among splendid female portraits, all united by the naturalness of the hair: and we are not only talking about finished portraits, such as that of Ginevra Benci, with her curls highlighted by accurate gilded highlights, but also about observing studies. For example, the one preserved at the Royal Library in Windsor, where the woman depicted by the artist assumes the same pose and attitude as the Scapigliata, with her face in three-quarter view, her eyelids lowered, her gaze lowered, and her hair moved by the wind. Then there is drawing 428 E in the Uffizi, where we see perhaps the most elaborate hairstyle ever invented by Leonardo (this is, moreover, one of the rare drawings dating from Leonardo’s apprenticeship period at Verrocchio’s workshop: curious to note how here the girl wears a headband with a necklace on her head; it was seen that later on this theme, in the Treatise on Painting, Leonardo would definitely change his mind), or again the young woman with her hair up in drawing 2376 in the Louvre, probably a study for the Madonna Litta preserved in the Hermitage in St. Petersburg. A wonderful female universe all united by natural hairstyles, which convey to the viewer all of Leonardo’s interest in this part of a woman’s body.

There are also other stylistic elements that argue in favor of attributing it to Leonardo: for example, Marani writes again, the “fusion between the movement of the hair and the surrounding air, between light and shadows blurred into each other ’in the guise of smoke’”, which “seems to reach in this panel one of the peaks, in terms of capacity for synthesis and means, of Leonardo’s art,” or again, taking up a comment by Adolfo Venturi, the “features delicately profiled by the soft shadow and the perfect oval of the face” (which the Emilian art historian compared with the drawings for Leda preserved in Windsor). Pedretti, who in 1985 called the problem of the panel’s authenticity “shelved,” focused instead on the sweetness of the sign, judged compatible with that found in Leonardo’s other works. Restorer Pinin Brambilla Barcilon, a profound connoisseur of Leonardo (she is responsible for the celebrated 20-year restoration of theLast Supper in Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan), wrote that "the expressive intensity of the face and the emotional state infused into this vibrant image are among the elements that most mark the impact with the Scapiliata.“ Brambilla Barcilon, moreover, analyzed the painting precisely on the occasion of the 2019 exhibition, finding several retouches referable to the restoration that the work underwent in the 19th century (especially in the area of the left eye, in his opinion: these are such retouches as to even alter the compositional balance). Certainly, according to Brambilla Barcilon, the sinuous locks made with broad brushstrokes on the sides of the head do not belong to Leonardo: ”they present a freedom of stroke that does not seem to me to correspond to Leonardo’s technique," she said. Probably, according to the restorer, it is the anomalies due to tampering in the 19th century that conditioned the judgment of Corrado Ricci (who also suspected, moreover, that the author of the Scapigliata was... Gaetano Callani!).

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Virgin of the Rocks (1493-1501; oil on panel, 189.5 x 120 cm; London, National Gallery) |

|

| Comparison of the Scapigliata and the Virgin of the Rocks. |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Study for Lacquering a Woman (c. 1504-1506; pen and ink on white paper, 92 x 112 mm; Windsor Castle, Royal Library) |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Head of Young Woman Looking Downward, Long Hair and Elaborate Hairstyle (pen and ink, diluted brush and ink, white lead, gray watercolor?, traces of black stone or lead tip on paper prepared with ivory color, 280 x 200 mm; Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe, inv. 428 E) |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Head of a Young Woman (lead point on paper, 179 x 168 mm; Paris, Louvre, Cabinet des Dessins, inv. 2376) |

|

| Bernardino Luini, Salome with a Servant and the Executioner Presenting the Head of the Baptist (c. 1525; oil on panel, 51 x 58 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

|

| Andrea Solario, Salome with the Head of the Baptist (first half of the 16th century; oil on panel, 59 x 58 cm; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum) |

|

| Giampietrino, Salome with a Servant and the Executioner Presenting the Head of the Baptist (c. 1510-1530; oil on panel, 68.6 x 57.2 cm; London, National Gallery) |

There is, finally, one last question worth exploring: who is the Scapigliata really? Who is that beautiful young woman she represents? Perhaps a study for a Madonna and Child, it has been thought in the past. Or a study for a Leda. Of course, we cannot know, but it is possible to formulate some hypotheses, starting with the most recent studies. In her 2016 contribution, art historian Carmen Bambach, a specialist on Leonardo, after accounting for the “sculptural modeling of the classical face” of the young woman, “delicately worked with a marble finish,” noted how there was a strong contrast between the completeness of the face and the sketchy state of the hair, shoulders and neck. An intentional contrast, according to Bambach, and it is precisely this intentionality that could, in her view, reveal interesting clues: the American scholar relates this element to Pliny’s description of a Venus by Apelles left unfinished, and according to the Roman writer it was precisely this unfinishedness that made Venus fascinating to her ancient admirers. Leonardo was in possession of Pliny’s Naturalis historia (we know this for a fact), and in addition the scholar Agostino Vespucci (Terricciola, 1462 - Newfoundland, 1515), author of some famous annotations on Leonardo da Vinci drafted in 1503, in one passage compares the great Tuscan to the Greek Apelles, and in yet another evokes Apelles’ Venus and its unfinished state. Might Leonardo have wanted to try his hand at imitating Apelles?

According to Marani, however, this would be too experimental an intent for a work of which we know of many derivations, which we find, in particular, in the art of Bernardino Luini (Dumenza, c. 1481 Milan, 1532): a sign that the work was most likely intended to be completed. Luini himself, however, may provide a key to who the Scapigliata might be: in one of his Salome with the Head of the Baptist preserved in the Uffizi Gallery, the face of Herod’s daughter is almost identical to that of the young woman preserved in the National Gallery in Parma. Another likely derivation is the Susanna in the Liechtenstein Museum in Vienna, a fragment of a larger work. Still in Vienna, a Salome by another Leonardesque, Andrea Solari (Milan, 1470 ca. 1524), displays a remarkable closeness to the Scapiliata. Somewhat more distant in rendering, but similar in idea, is Giampietrino ’s Salome now in the National Gallery in London. In short, there are many works with a biblical theme that show a clear derivation from the Scapigliata, as well as attesting to its fortune (and providing an argument for the goodness of the attribution to Leonardo): the Parma panel could therefore be, Marani concludes, “the study for a composition having one of these themes for subject.” Destined therefore to resonate for a long time. A work that remained in Parma thanks to its former owner’s great love for Leonardo, and a work that, from its room in the National Gallery, continues to convey today to those who admire it all the innovative originality of Leonardo’s flair and inventions.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.