Gaudenzian cartoons in Turin's Pinacoteca Albertina, a unique Renaissance treasure in the world

The Pinacoteca Albertina in Turin preserves an important nucleus of 59 cartoons by Gaudenzio Ferrari and artists of his school such as Bernardino Lanino and Gerolamo Giovenone: it is a very rare Renaissance treasure, unique in the world, extraordinarily well preserved.

By Federico Giannini | 09/03/2025 15:54

It makes no noise, the brush brushing against the canvas. Not even a slight rustle, not even the faintest crinkle. The bristles distribute the color caressing the surface of the canvas without making themselves heard. The paintings are born in silence. One is then under the illusion of being alone, here, among the rooms of Turin's Pinacoteca Albertina, as an early winter Monday afternoon begins. Ideal day and time for a visit in complete calm, certainly. But not in complete solitude. Somewhat because soon, after the lunch break is over, the first students from the Academy, who habitually attend the Pinacoteca, will begin to arrive. Maybe a few tourists passing through will be added as well. And a little because you are actually not alone, even if you don't hear any noise. In almost every room of the Pinacoteca are the students of the adult painting course that the Albertina Academy of Fine Arts regularly organizes, encouraging aspiring painters to work directly in front of the works. As has always been done in the academies.

The Pinacoteca Albertina has never lost its identity as an academic art collection, the museum's head of external relations, Enrico Zanellati, tells us as he takes us on a tour. Elsewhere, museums created to provide exempla galleries for the students of an academy have followed other fates: some have become autonomous, have become bodies detached from the educational institutions with which they were born, others have taken on different connotations, have become world-famous for the works they house, so much so that their initial didactic vocation is almost no longer perceived, although they continue to be frequented by students of the academies for which they were created. Here, at the Albertina, this inclination is instead strong, it is felt, fostered, proudly claimed. It happens frequently, then, that visitors to the Pinacoteca meet, while wandering through the rooms, painters practicing in front of the works in the collection. A discreet, silent presence. That encounter, which is becoming increasingly rare in Italian museums, is instead quite usual here. A student has just set up his easel in front of Vittorio Amedeo Rapous' Saint Luke : he still has to arrange the canvas, he has just arrived. There is a lady, on the other hand, who has almost finished reproducing, with some diligence, one of the museum's masterpieces, Giuseppe Pietro Bagetti's Plenilunio sul mare. Another has just begun sketching a detail of a copy of Guido Reni's Saint Sebastian . A copy squared, in short. Here, then, in these halls is renewed almost daily that ritual that has animated the academies of fine arts for centuries, ever since they were born. Today's painters do what their colleagues did three, four, five hundred years ago. Copying the greats. But you can go even further back in time, you can go back to before the mid-sixteenth century, to before when Vasari founded the first academy in history in Florence: before the schools where people received a formal education came into being, artists did the same thing in the workshops of their masters.

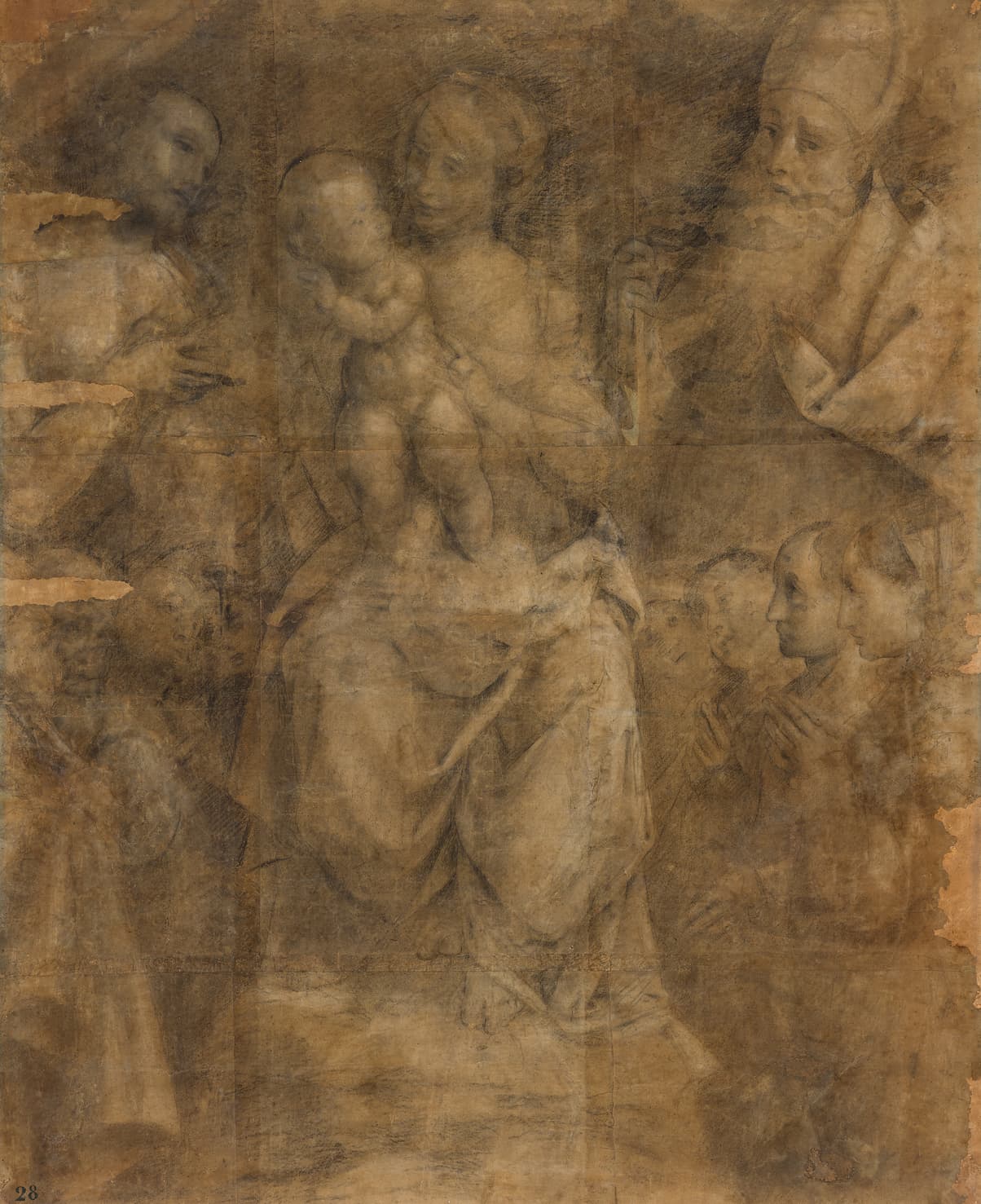

One inevitably thinks of these historical continuities when one crosses a curtain and enters the dark room that presents visitors to the Pinacoteca with the precious fruits of the labor of a Renaissance school, that of Gaudenzio Ferrari: the collection of Gaudenzio's cartoons and those of his pupils, which roughly recount one hundred years of the history of the workshop started in Vercelli by the Valsesian painter and carried on by his heirs, capable of perpetuating the ideas of the master who had been able to renew Piedmontese painting by looking to Leonardo da Vinci, to the Milan of Foppa and Zenale, but also to northern artists and those from the Umbrian-Tuscan area. These cartoons are the treasure of the Pinacoteca. "A unique corpus in the world," defined the president of the Academy, Paola Gribaudo: "they are a source of pride for our Pinacoteca, which preserves them with great care, extraordinary works of art that allow us to enter the workshops of the 16th century, discovering how artistic education took place in the Renaissance, before the birth of the Academies of Fine Arts." They are largely cartoons made in preparation for paintings later made by Gaudenzio Ferrari and the students of his workshop or his heirs. There are cartoons by him, by Girolamo Giovenone, by Bernardino Lanino, by Giuseppe Giovenone il Giovane, and by Giovanni Pietro Lomazzo, while others more generically refer to the workshop. Fifty-nine in all. Perhaps no other museum has so many.

Enrico Zanellati is at pains to emphasize the uniqueness of this incredible collection nucleus. It is already not easy for a sixteenth-century cartoon to arrive intact until today: at the time, cartoons were considered objects of common use, working tools, tools to be used in daily practice. Not much attention was paid to their preservation. And so it is very rare to come across such substantial cores of cartons referable to a single school. It is very rare for them to have come down to us in such a good state of preservation, considering their use: the cartoons were not only used to transfer the artist's ideas onto the final support, but were not infrequently used by workshop students for their exercises. It is very rare that anyone kept them all together. And it is very rare that the last owner decided to give them en bloc to a museum.

The Gaudenzian cartoons have been part of the collection of the Pinacoteca Albertina since 1832, when King Carlo Alberto decided to donate them to the Academy so that the students would have an additional base on which to practice. They have been carefully preserved ever since, and if before this marvel was the exclusive patrimony of the students, today it has become the patrimony of everyone. The Academy has invested heavily in bringing out the value of this exceptional graphic corpus . When we enter the room that preserves them, the lights are off: the recent rearrangement, in 2019, financed by the Consulta Valorizzazione Beni Artistici e Culturali di Torino, introduced a lighting system based on sensors that turn on the projectors whenever the passage of visitors is perceived, because the cartoons are fragile and cannot stay too long under the light, which would risk ruining them irreparably. Not only that: the designers of the installation, namely Diego Giachello, Michele Cirone and Alessia Canepari, evidently imagined to make the visitor's experience evocative, because the light is gradual, making the cartons emerge little by little from the half-light, and the projectors have been placed in such a way as to illuminate only the cartons, almost as if they were floating in the dark. There is no ambient light at all. It's like seeing them by candlelight. Some have been mounted on panels that slide on rails, a solution designed to allow all the pieces in the collection to be displayed. Finally, a multimedia monitor in the center of the room offers visitors a detailed guide, also allowing them to compare the works and see details that the naked eye may miss.

Giovanni Testori, who was Gaudenzio Ferrari's greatest exegete, offered a metaphorical, poetic image to describe these cartoons: he saw them "as sheets, pillowcases, tablecloths on which the embroidery and 'figures' were the work of the mother, but the imprint of the whole family, having the father at the head of the table.", she was certain that they were "like the 'dowry,' which, in the houses of old, was prepared for the daughters, [...] ready, for the day when they left to marry." The eyes linger on the Lamentation over the Dead Christ, the most shining, illustrious example of Gaudenzian graphics preserved here: it is the preparatory cartoon for the work that is now in the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest, but was once in a private collection in Milan. "The scene," writes Alberto Cottino in the museum's official guide, "is intense, marked by a strong and heartfelt patheticism, in which the luminous body of Christ, with its strong physicality, is presented to the viewer, held frontally by the Madonna who opens her mouth wide in a stifled cry, while the Marys, a saint on the upper left and St. John the Evangelist on the right show signs of their devotion." The softnesses are still those of Leonardo da Vinci, the intense, pained expressiveness is that of Lombard painting that Gaudentius had been able to modernize to sprinkle life into the actors of his stories, to convey through the eyes of his characters the story of the passions of human beings. It is art that mixes with theater, Gaudentius's. He had given supreme proof of it at the Sacro Monte of Varallo; he would continue to give proof of it in his paintings. And, of course, also in his cartoons.

When there was no story to tell, as in the Lamentation, Gaudentius still managed to present himself as a modern artist: the cartoon with St. Agabio of Novara and St. Paul, preparatory for the polyptych of the high altar of the basilica of San Gaudenzio in Novara, succeeds in giving back to the relative two animated figures even in their monumentality built by means of strong chiaroscuro. The cartoons are then useful for gaining insight into the working method of Gaudentius and his workshop: in the figure of St. Agabius, for example, the blessing hand is drawn in two different positions, a sign that the artist was experimenting with various solutions for the final drafting. There is then often in the cartoons a freshness, a liveliness that is not infrequently lost in the finished work, since when moving on to painting Gaudenzio Ferrari frequently resorted to workshop assistants. The cartoons, on the other hand, are the most immediate fruit of his inventiveness, his imagination. It is on the drawing that you see the artist at work. And that is why drawing is so fascinating.

Monumental is also the registemma angel, monumental the two Madonnas with Child, and then there are the works of his continuators. More gentle and measured is Bernardino Lanino, who touches on achievements of surprising delicacy in theAdoration of the Magi and turns the sacred epiphany of Christ with the instruments of the Passion into an air of expressions and clouds. In many of Lanino's cartoons vivid reminders of Leonardo emerge: it happens, for example, in the soft Marriage of the Virgin, or in the delicate Madonna and Child among Saints and Devotees, and sometimes the quotation is direct, since the Madonna and Child with St. Anne , which reproduces the well-known original by Leonardo da Vinci, is also preserved in the Gaudenzian core of cartoons. And then there is Girolamo Giovenone: of him there are some monumental figures of saints and Madonnas, echoing the manner of Gaudenzio Ferrari while bringing in some personal interpretations (for his Madonna and Child, for example, one can read a desire to tone down the exuberance of Gaudenzian expressionism and, at the same time, an attempt to 'move closer to a sculptural framework that seems to be of Nordic derivation), and there are also some things from his entourage that can be considered derivations, exercises, reworkings, such as the sharp cartoon of theLast Supper, considered for some time to be a model for theLast Supper in Novara Cathedral, a work by Sperindio Cagnoli executed to a drawing by Gaudentius, but actually derived from this prototype.

We do not know in detail the history of these cartoons before Charles Albert's donation. However, we still owe to him the adjective "Albertina" that has accompanied the name of the Turin academy for two centuries: the institute had been founded in 1678 by Maria Giovanna Battista of Savoy, but it was Charles Albert who had donated to the academy the building in which it still has its headquarters. Out of gratitude, the school would be named after the sovereign. The cartoons, before being donated to the academy, were kept in the Royal Archives, but we do not know when they entered the Savoy collections. It is enough for us to know that it is as a result of that donation that today we can enjoy this patrimony, as fragile as it is precious, a patrimony that is revealed in the soft light of the new display, to which we owe the desire to exalt this little-known gem of Turin's heritage.

But in fact it could be said to be a heritage of the whole region, since the spirit of Gaudentius and the heirs of his school presides over an entire territory, stretching from the mountains of Valsesia to the plains of Novara and Vercelli, passing, of course, through Turin, and going further afield to Lombardy. The inventions that Gaudenzio and his heirs fixed on these large sheets of pasted paper impregnated a land that for a hundred years or more saw in their works a translation in images of that renewed sense of faith that started from the Sacred Mountains in the mountains around Lake Maggiore, spread to the plains, among the reclamations and rice fields, to the cities and in the countryside, and manifested itself in a "new oral style," wrote Maurizio Cecchetti, "where faith speaks, shouts, bleeds, weeps, loves and rejoices in the celebration of sacred representations and processions where the moments of Christ's life up to Calvary are relived, taking up certain modules of popular theater that becomes sacred theater." It is this sentiment at the origin of a language that Gaudenzio Ferrari's school would continue to speak for more than a century, and perhaps it is also this sentiment that led the Vercelli artists to understand the cartoons as a kind of tool suitable for perpetuating a tradition. We do not know what ideas they had about the cartoons, but we like to think, by virtue of the consistency of the core of the Albertina and by virtue of that feeling so strong and persistent, that this didactic value was not only felt but also proudly upheld.