Prague's National Gallery, the charm of an eclectic capital through its masterpieces

Prague's Národní galerie is an outstanding museum system, spanning from the Middle Ages to contemporary art, with great masterpieces of European painting. One way to get to know one of the world's most eclectic capitals through its works of art.

By Jacopo Suggi | 25/01/2025 16:42

Prague, among Europe's capitals, is perhaps the city that assimilates the most souls: it has in fact, throughout its very long history, been the administrative and political center of the Kingdom of Bohemia and the Holy Roman Empire, the "blossoming Mittel-European" (to use a fortunate definition by Franco Cardini) under Habsburg rule, and then later an attempt at synthesis between socialism and the West, and much more. Here, where Protestant ethics and Jesuit morality coexisted side by side, and where a thriving Jewish community developed, Slavic characters are also grafted in. In the city, the contrasts seem to find a compromise between nationalistic yearnings and international ambitions: the scene of Kafka's surrealism and Kupka's cubist rationalism, nestled between East and West and North and South, told by millions of ink words, set to melody by the greatest composers, Prague is as multifaceted and brilliant as a Bohemian crystal.

This complexity is partly rendered by the Národní Galerie (National Gallery), which is an art museum organized in several locations scattered throughout the vast urban center of the Czech capital, an institution that in size and quality has a right to rank alongside the most important European museums, although it may not enjoy the same fame.

The wealth and power of the city of Prague during the long Middle Ages are reflected in the works on display in the Convent of St. Agnes in the Old Town. The ancient monastery was founded by Agnes of Bohemia, the youngest daughter of Ottokar I, the first king of Bohemia: in her father's plans, she was supposed to be married to Emperor Frederick II, but instead chose to take vows (she was later canonized in 1989). Next to the monumental and striking Gothic church, where the saint and some members of the royal Přemyslide dynasty rest under ogival vaults, the exhibition space unfolds. Inside it are works dated from 1200 to 1550, mute witnesses to the kingdom's intricate history of changing dynasties and fluctuating fortunes, which certainly peaked in the second half of the 14th century with Charles IV of Luxembourg, the ruler who effectively moved the capital of the Holy Roman Empire to Prague, transforming the city with the building of the famous Charles Bridge, the cathedral and one of the first universities in Europe. The ruler, who was a man of culture, in contact with the greats of his time, such as Petrarch, surrounded himself with artists who knew how to combine local traditions with the innovations that came from Italy.

Among the most interesting is the bizarre and mysterious figure of Master Theodoric, a court painter, of whom few works are known, some miniatures, as well as the decorative cycle of the Chapel of the Holy Cross in Karlštejn Castle, where the imperial treasure and relics of the Passion were kept. For this place, the painter produced 133 painted panels in the mid-14th century, with towers of angels, saints and prophets, organized according to a complex hierarchy. Several panels from this imposing worksite are preserved in the museum, and they are works of great expressive force, where the saints monumentally occupy all the available space, even partially invading the frames, and displaying a physiognomic typification that seems to reveal a knowledge of the production of Vitale da Bologna and Tomaso da Modena, perhaps known during a trip to Italy following Charles IV.

But Italian models seem instead to be replaced by examples of French Gothic in statuary, as seen in a delightful sculpture known as Michle's Madonna, works by an unknown author to whom a small core of sculpture is attributed. The group with Madonna and Child carved in pear wood is perhaps the most significant example of the linear rhythmic style in Bohemia derived from the stone carvings of central France. While the much later panel with the Death of the Virgin from the Altar of St. George betrays derivations from the Dutch school, constituting, as critic Jaroslav Pešinam wrote, one of the "first and supreme manifestations of the new stylistic aesthetic on Czech soil."

As the visit continues, the panorama of Bohemian art capable of combining themes and forms drawn from a common European heritage, with autonomous creative accents of great quality takes shape, a certain morbid taste for the grotesque and death, perhaps a legacy of the long periods of the Hussite wars, and a great attention to domestic detail reflected in paintings such as St. Agnes Healing a Sick Man, where a dwelling of the time with its furnishings is minutely described.

The museum contains numerous other masterpieces, enhanced by a setting of rare beauty that, through the use of panels and finishes in stone, metal and concrete, succeeds in restoring the atmospheres typical of the sacred environments for which the exhibits were originally designed. No less artistic intensity emanates from the two Old masters collections, although the role of local artists is reduced to a smidgen. They are housed in two sumptuous buildings that face each other and frame the square where the entrance to the imposing Prague Castle is located.

The Renaissance Schwarzenberg Palace houses the most lofty names, works and authors that were the object of the collecting interest of Rudolf II, the emperor who, having ascended the throne, decided after a few years to move the court and consequently the capital to Prague once again. He has ungenerously gone down in history as the ruler capable of squandering his power and inheritance to devote himself full-time to collecting and the study of the occult. Great cultural figures such as Tycho Brahe, Kepler, Giordano Bruno, Arcimboldo and many others were his protégés.

He fostered a flourishing season of Mannerism and put together a gigantic collection, much of which was later destroyed and dismembered by his heirs and the various wars. Among the purchases made by the Emperor that are still preserved in the Prague museum is a masterpiece by Albrecht Dürer, The Feast of the Rosary. It is a large canvas commissioned from the artist by the Venetian German community, for the church of San Bartolomeo a Rialto in the lagoon city. The work had wide acclaim among contemporaries, including Giovanni Bellini and Doge Leonardo Loredan, who on that occasion offered the German the role of painter of the Serenissima, which, however, he declined.

The painting grounded in brisk chromatics shows a majestic and crowded composition, where the spectators of the sacred moment stand as essays of great portraiture, among whom Pope Sixtus IV and Emperor Maximilian I can be recognized, as well as Dürer's own self-portrait. Also from the celebrated Emperor's Wunderkammer comes the horse bronze by Adriaen de Vries, which in its marching pose shows off that naturalistic search for figures involuted in dynamic and free movements typical of Giambologna's works. Also probably of imperial commission is Hans von Aachen 's painting of the Suicide of Lucretia, where a nude of elegant modeling and casual sprezzatura is veined with a persuasive erotic charge, exhibiting those features of the Mannerism developed under Rudolph.

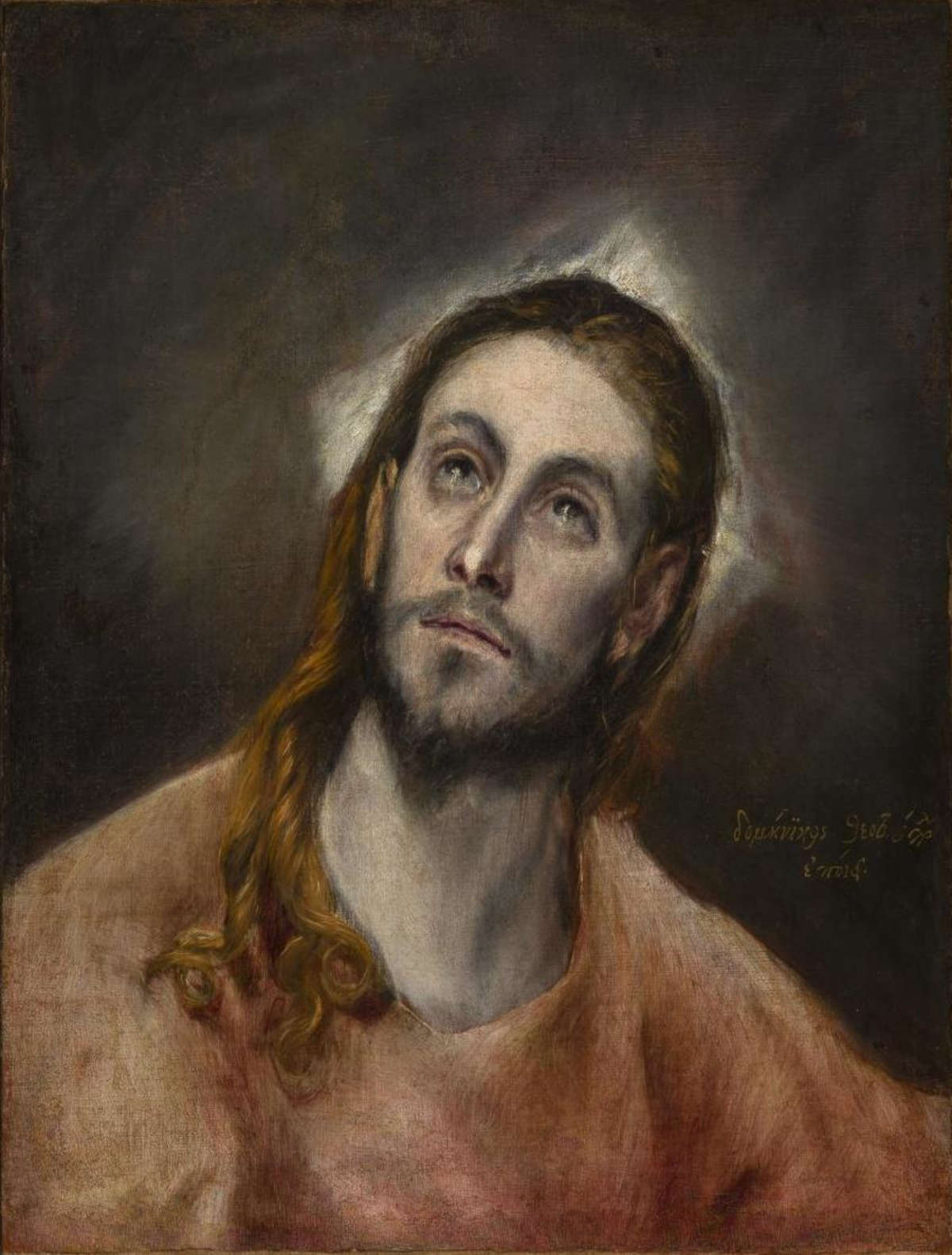

Still numerous are the museum's masterpieces, in part from the collection of Archduke Francesco Ferdinando d'Este and those of aristocrats, among which it is worth mentioning important works by Bronzino such as thePortrait of Cosimo I and that of his consort Eleonora di Toledo, a sumptuous polyptych by Antonio Vivarini, several fascinating paintings of the German school including by Hans Holbein the Elder and Lucas Cranach, a canvas depicting a Christ of rare and distinct humanity by El Greco.

The Baroque section is also extraordinarily rich: works include a Suicide of Lucretia by Simon Vouet, from the collection of Cardinal Mazzarino, among the pictorial high points of the Frenchman's Italian experience at the time strongly influenced by Guido Reni, and then an excellent quality portrait of a Scholar in Middle Eastern Dress by Rembrandt, the only work by the Dutchman in Czech public collections. The valuable collection testifies to the collecting taste of the cultured Bohemian aristocracy, which made Prague one of the centers of Baroque and Rococo development, with many local artists who were able to pick up the lesson of Rubens (also present in the museum), known through a number of works created for churches in the Czech capital, a trend led by leading painters such as Karel Škréta, Petr Brandl, and the sculptor Mathias Bernard Braun.

The Old masters II collection continues in the baroque Palazzo Sternberg, where visitors are greeted by Lorenzo Costa 's impressive canvas depicting theInvestiture of Federico Gonzaga as Captain of the Church, looted in the 17th century from the San Sebastiano Palace in Mantua. Breathtaking is the long room where a collection of Russian Christian icons and the largest collection of Italian primitives preserved outside Italy are housed, which is owed in particular to Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria. This very numerous parade of gold panels, which protrude from each side of the room, shows important names of protagonists active in Siena, Florence, Venice or Padua, from Lorenzetti to Lorenzo Monaco, and then Andrea di Giusto, Vivarini and many others. The museum holds other fine paintings such as a Dosso Dossi, Alessandro Allori, Jacopo Bassano, and Jusepe Ribera, essays on Flemish and Dutch painting, including Pieter Brueghel the Younger, Anthony van Dyck, and Frans Hals. Among the most jaw-dropping pieces is the large retable with the Passion of Christ cycle painted by Hans Raphon. The work signed with the date 1499 originally had 41 panels and was made for a church in Göttingen, Lower Saxony. During the Thirty Years' War to save it from Swedish troops it was taken to Prague, where today 13 panels are preserved, divided between those representing the life of Christ and episodes that occurred after death, all scenes carried out with great vividness and narrative effectiveness.

But the real highlight of the National Gallery is the endless collection of modern and contemporary art housed in the Fair Palace, a gigantic building, a jewel of Czech functionalist architecture, located in the northern part of the city, defiladed from the historic center. The concrete building dates back to the 1820s, when it was built to house trade and mercantile fairs. Inside, it has eight floors articulated around a central atrium onto which scenic galleries and balconies are grafted. The collection itself is divided into numerous themes and exhibits that have the merit of not adopting purely chronological criteria or by schools, but that in a continuous manner presentCzech art in comparison with international art.

The first section offers an insight into public statuary in the Czech Republic, showing sculptures and sketches that accompanied monumental achievements, displaying an amalgamation of neoclassical, Art Nouveau, verist, cubist, and rationalist forms. This is followed by the permanent exhibition 1796-1918: Art of the Long Century, through which one can follow not only the vicissitudes of local and international art, but also the collecting taste that led to the musealization of certain works. The dates that identify this partition refer as the beginning to the founding of theSociety of Patriotic Friends of the Arts in Prague, a reality that gave considerable impetus to the development of the arts in Czech lands, founding the museum and concomitantly the Academy of Fine Arts, and as the end the independence of the state from the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Prague's cultural art milieu remained for a long time in obvious connection with that of Vienna, and to some extent with Munich, until the Empire dissolved after World War I: with the birth of the Czechoslovak Republic these lands ceased to aspire to pro-Austrian models in order to elect Paris as their main reference, and the museum began to be filled with key paintings by the main protagonists of French art.

From the triumph of patriotic historicism, through lyrical Romantic accents à la Delacroix (present in the museum with some dazzling paintings), verism and impressionism, to the expressionist symbolism of Franz von Stuck (whose numerous paintings are included), to the intersection of Jugendstil, Art nouveau and Secession stylistic features, and on to the avant-garde's quests of cubism, fauve and abstraction. This kaleidoscope of forms and colors overflows from all parts of the museum, and it is almost the same trajectory that František Kupka, a Czech painter who knew how to experiment in all directions and whose work is preserved in the museum, seems to have traversed with his art.

However, it remains a daunting task to attempt to describe an exhibition organized as so much hypertextual content around numerous themes that compare very different artists.

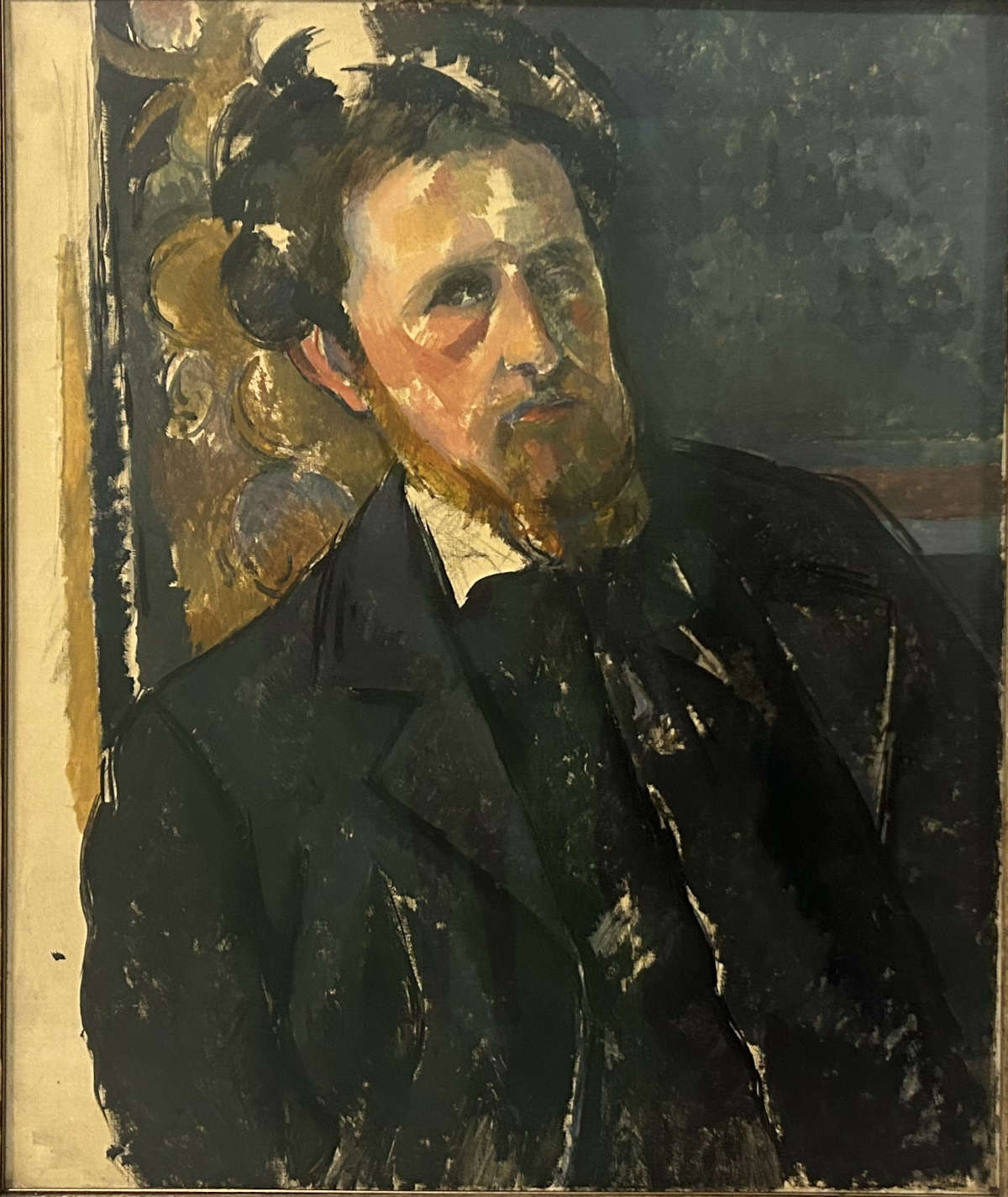

The section on portraits places academic painters alongside absolute works of international art history such as Paul Cézanne's Portrait of Joachim Gasquet, a biographer of the French artist, critic and philosopher, which is rendered with great plastic force without the use of chiaroscuro.

This is followed by a very delicate portrait of Antonin Proust by Édouard Manet, a self-portrait by Pablo Picasso painted in the same year as Les demoiselles d'Avignon , and the extraordinary I, portrait-painting of the customs officer Rousseau, which shows a new maturity of art, capable of freeing itself from all rules of representation to ensure greater expressive effectiveness. Alongside these sacred monsters appear without embarrassment a number of Czech artists, Bohumil Kubišta, Emil Filla, the aforementioned Kupka, and many other painters of great talent.

The section 1796-1918: Art of the Long Century showcases a variety of other masterpieces from the hallucinatory portraits of Oskar Kokoschka, to the decadence of flesh and forms that came out of Egon Schiele's brush, the social denunciations of Honoré Daumier, and the ongoing researches of Picasso capable with Seated Nude of heralding the stylistic outcomes of the return toorder and Mediterranean painting of later years, the coloristic and existential explosion of Gustav Klimt's Virgin, to Alfred Mucha 's Parisian Art nouveau adventure or Paul Gauguin's refuge in primitivism.

Continuing through the floors, First Czechoslovak Republic presents the production of the Czechoslovak state from 1918 to 1938. The itinerary divides the spaces by immersing visitors in the exhibition environments of the time, where alongside local artists again appear the big international names, such as that of Matisse, Van Gogh or Renoir. The rooms are ordered to restore the visual and creative climate of the various cultural centers divided by city, and the artworks, which are not limited only to paintings and sculptures but include books, design, graphics and theater, are presented not as isolated artifacts but as elements of a complex system of social and institutional relations, reconstructing a layered art scene.

Complementing the visit are the other two permanent sections End of The Black-and-White Era and 1956-1989: Architecture for All. The former presents a long reflection by proposing the artworks as a record of the times, a set of forces not only purely authorial but also social, political and economic. The works reflect the succession of events, the public commissions of the communist regime, the isolation from an international scene, the libertarian yearnings that accompanied the Velvet Revolution , and much more. The last exhibition, on the other hand, investigates the phenomenon of architecture from an industrial to a postindustrial reality, new conceptions of inhabiting space, and the collectivist life projects of socialism. Numerous temporary exhibitions complete the itinerary.

Through multiple venues and jagged collections, among which one entirely devoted toAsian art should also be added, the National Gallery in Prague offers a varied artistic universe, where art is not presented, as per consummate tradition, in an ever-evolving parable of movements and authors, but is restored in its complexity, analyzing its context, the interrelationships between the period and society, restoring to art its polyvalence of values that are not limited only to the mere aesthetic experiment, but that makes it an artifact, a living testimony of a community with its own concerns and yearnings.

Embellishing the offer is a plurality of venues of high architectural and installation value, which house not only numerous temporary exhibitions (making the itinerary constantly evolving) but also gardens and splendid spaces for relaxation. Visiting the Národní galerie comes to use the words of Angelo Maria Ripellino in his famous book Prague Magic, when he wrote "There will be no end to the fascination, the life of Prague."