The Malatesta Temple in Rimini, the Renaissance dream of Sigismondo Malatesta

The Malatesta Temple in Rimini is one of the symbols of the Italian Renaissance: it was born as a mirror of the ambitions of the lord who wanted it, Sigismondo Malatesta, a ruler doomed by history who celebrated his family and his love for Isotta degli Atti here.

By Federico Giannini | 05/01/2025 13:46

It feels like entering a pagan temple. Or a sumptuous noble residence, if you prefer. When one enters the Malatesta Temple, one immediately gets the distinct impression that the glory of the Christian pantheon was not exactly high on the list of priorities of Sigismondo Malatesta, the lord of Rimini who wanted to have this church built, this monument to his ambitions. Although, rather than ambitions, one might speak of velleities. And the Temple's state of unfinishedness becomes a visual synonym for that desire to make the small, marginal lordship of Rimini a strong state, one that could expand at the expense of its neighbors. True: Sigismondo Malatesta could be blamed for his lack of loyalty to allies, his excessive aggressiveness, his irascible temperament, the fact that he antagonized many of the most powerful rulers of the Renaissance, his often instinctive actions. But he could not be blamed for not loving his city. So much so that when Pope Paul II, in 1467, asked him to consider ceding Rimini to the Church in exchange for certain benefits Sigismondo had requested after his unsuccessful participation in the war in Morea against the Turks, the proud Malatesta considered that he would never have ceded "that poor city that is left to me, where most of the bones of my antiqui are." Sigismund would have preferred "to die with honore than to receive such vilification," and he told the pope himself: indeed, he would have died a thousand times rather than be forced to suffer such a disgrace. Stubbornness would later reward Sigismund, who at the end of his days, defeated, disillusioned, in financial distress, still managed to keep his Rimini.

History, it is known, is written by the victors. And Sigismondo Malatesta's victors spread a picture of the lord of Rimini in very dark hues, so much so that for a long time he was hastily, and unfairly, regarded as a kind of ignorant, uncouth, bloodthirsty tyrant. Indeed, few Renaissance figures give off a charm comparable to that surrounding Sigismondo Malatesta, a charm that permeates every stone of the Malatesta Temple, built on the site of the ancient church of San Francesco in the late 1540s, when Sigismondo was at the height of his glory. Successful military campaigns had brought him substantial earnings, through which the lord of Rimini had been able to devote himself to what he perhaps most truly loved: art. Sigismondo thus gathered in Romagna a fine array of poets (and he himself was a poet), intellectuals, men of letters, and artists. Through the work of his protégés, Malatesta intended to celebrate his family, to exalt it as if it were the object of a cult, the central figure of a singular religion. And, like other lords of the time, Sigismondo himself sought to link the history of his own family, as well as his own person, to a repertoire of ancient symbols. The Malatesta Temple would become the most dazzling evidence of this cultural policy, the house built to the eternal glory of the lords of Rimini.

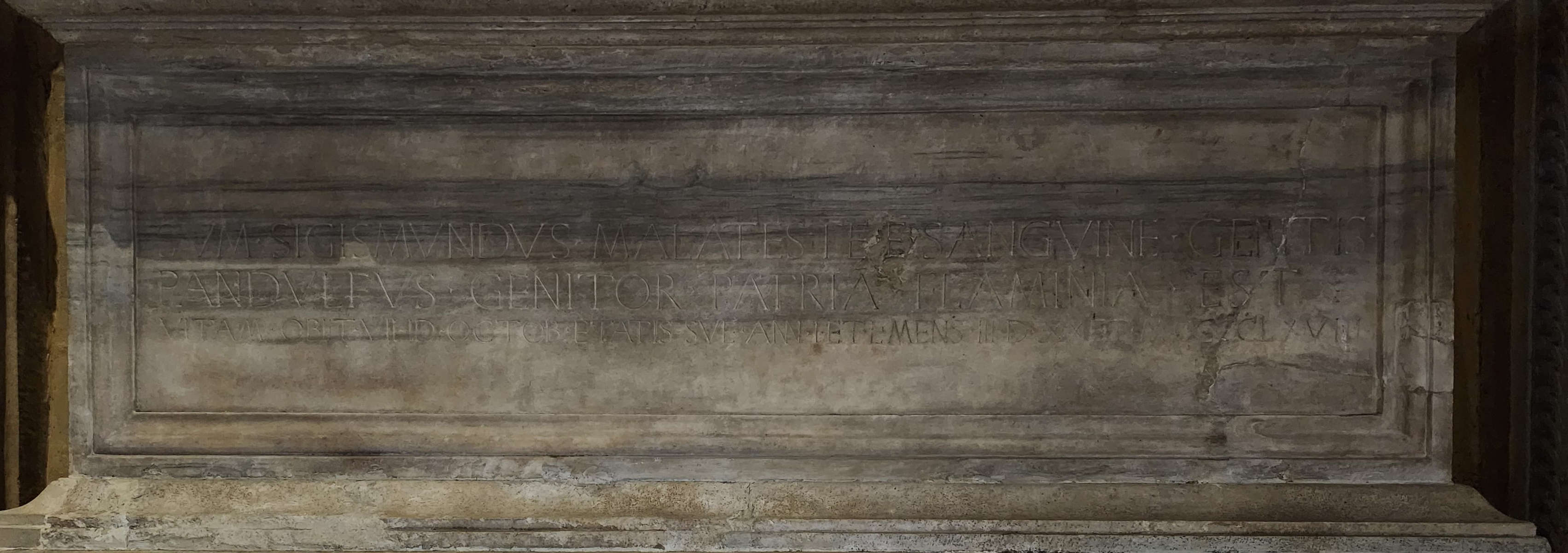

Sigismondo entrusted the plans to Leon Battista Alberti, who was given the task of arranging the exterior, and to Matteo de' Pasti, who was called instead to revise the interior. The construction started from the inside, in 1447, and a few years later, around 1453, Alberti entered the scene, who designed a temple with a totally innovative conception. For the facade he would adopt the typical structure of the Roman triumphal arch, taking broad inspiration from the Arch of Augustus in Rimini, located just a stone's throw from the area on which the Temple stands. No one before had ever attempted something even vaguely similar: for the first time, the facade of a church was inspired by a Roman triumphal arch. The main arch of the façade, the one framing the portal, was to be flanked by two side arches that were supposed to accommodate the tombs of Sigismund and his beloved, Isotta degli Atti, then placed instead inside the church, with the result that the side arches of the façade today are less deep than they should have been according to the original design. And then, like the ancient temples, the Malatesta Temple also rests on a high stylobate, the horizontal plane on which the columns stand. The unfinished state of the church does not prevent us from appreciating what is in fact the first practical application of Leon Battista Alberti's theories, also expressed in his treatise De re aedificatoria, about architecture inspired directly by the ancient, understood as harmony, rigorous simplicity, rightness of proportion. Crowning the facade of the temple is the frieze on which runs the celebration of the lord, in Latin: "Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta, son of Pandolfo, realized by vow in the year of grace 1450." The inscription is not just a vindication: we can read it as a sort of political manifesto, and not only because Sigismondo wanted to make it clear to all to whom the Temple feat was due: 1450 was a jubilee year, as well as the year in which Pope Nicholas V renewed the apostolic vicariate to both Sigismondo and his younger brother Domenico, known as Malatesta Novello, lord of Cesena. And on the same occasion, the pope also legitimized Sigismondo's two male sons and guaranteed the vicariate to the Malatesta family for three generations. Sigismondo regarded all this as the final investiture of a strong dynasty set on a high destiny. And the Temple was to be considered a kind of mausoleum for the family.

The apostolic vicariate had conferred prestige on the household, but the ambitious Sigismund wanted more. Titles, money, territories, glory. But he could not know that he was experiencing his apogee, and that his fate, in fact, was to see his ambitions frustrated. Ambitions that, at that very time, had been fanning the flames of the clash between Rimini and the papacy. The fire was about to become a blaze, but Sigismondo could not have known that. And he could still afford to defy papal authority. Even inside his own temple. That masterpiece that is Piero della Francesca's 1451 fresco of Sigismondo Malatesta praying before St. Sigismund can also be read as a provocation. The eponymous saint of Sigismund, the first barbarian saint of the Catholic Church, the ancient king of the Burgundians who lived in the 6th century, is not depicted according to the typical iconography, that is, with youthful features, but rather as an aged man, holding a scepter with one hand and holding a globe with the other: Saint Sigismund was depicted with the typical symbols of imperial power and with the features of the late Emperor Sigismund of Luxembourg, who in 1433 had granted the title of knight to Sigismondo Malatesta, then just 16 years old, thus conferring imperial legitimacy on his power and his family. The message is clear: Sigismondo Malatesta openly declares his loyalty to imperial power, especially since two dogs, symbols of loyalty and vigilance, also appear in the image. But Piero della Francesca's fresco was not the only image with which Sigismondo Malatesta challenged the papacy. The first chapel on the right, the Chapel of St. Sigismund, conceived as Sigismondo's funeral chapel after he resolved to house the tomb inside the Temple, is adorned with figures of the Virtues, splendid works by Agostino di Duccio, usually reserved for the burials of kings and princes, or at any rate rulers eager to recall with allegories what good had been done during their rule. Sigismund's idea, in essence, was to present himself to the world as a powerful, valiant, beloved dominus .

Everywhere, among the stones of the temple, on the shields of Agostino di Duccio's angels, typical Malatesta symbols recur, beginning with the elephant: it is found as a helmet crest, at the base of pillars and columns, used as a decorative element, and even as a support for the tomb of Isotta degli Atti. It is a symbol of strength, power, imperturbability: Malatesta Novello's motto was elephas indus culices non timet, "the Indian elephant does not fear mosquitoes," as if to say that large people do not care for the annoyances brought by small ones. And then the feat of the three heads, which visually recalls the name of the Malatesta family because it depicts the heads of the three Moors (hence infidels, bad heads, "evil heads") killed by the legendary founder of the lineage, the mythical Trojan hero Tarcone, son of the Trojan king Laomedon. The dog rose appears often, which can also be admired among the coffers that adorn the arch of Sigismondo's tomb: it was the effigy by which the Malatesta family claimed descent from the Roman family of the Scipiones whose symbol was the four-petaled rose. And everywhere the symbol of the intertwined S and I recurs: it is the first syllable of the name Sigismondo, but in the past there were those who believed, and perhaps still do, that it was actually the initials of the names of Sigismondo and Isotta, eager to seal their love between the chapels of the temple. Not so, the romantic reading ill suits the usages of the Renaissance and the recurrence of that syllable even in contexts that have nothing to do with Isolde. But lovers who dream of a love like that between Sigismund and Isolde be accommodated: the story of their love is worth more than one syllable.

Isotta degli Atti was fifteen years younger than Sigismondo Malatesta. She was not of noble origins: she was the daughter of a wealthy merchant of Marche origin. The two probably became lovers when Isotta was thirteen or so, and Sigismondo was just under thirty: the age difference, for the time, was not a big deal. Then, when Sigismondo's first wife, Polissena Sforza, died in 1449, the affair became public, and a few years later, in 1456, the lord was finally able to marry the woman he had loved with true love. The marriage between Sigismondo and Isotta was one of the rare disinterested marriages of the Renaissance: by marrying Isotta, Sigismondo would gain no political advantage (except for the legitimation of the children she had outside of marriage), but he would fulfill the dream that the reason of state had not allowed him to see fulfilled. The love between the two was so intense, so passionate, that it even gave rise to a literary strand at the Rimini court, that of Isottean poetry. Sigismondo is also credited with a sonnet dedicated to Isolde ("O vague and sweet light haughty soul! / Gentle creature, O worthy face, / O clear angelic and benign light / In which alone virtue my mind hopes").

Sigismund had thought of celebrating Isolde from the earliest plans for the Temple, in 1447, when they were not yet married, when Polyxena was still alive: but at that time, one knows, marriages were not celebrated for love. Besides, it was no mystery that the lord of Rimini cultivated his relationship with Isolde outside the bonds of marriage. Isotta's tomb thus occupies a prominent position within the Temple: it is located in the chapel of San Michele, where it occupies an entire wall, adorned with a pronounced late Gothic decorativism that follows one of the peculiar characteristics of the Malatesta Temple, namely the contrast between the accomplishedly Renaissance exterior and the interior still linked to the courtly Gothic style. That tomb, consecrated as early as 1450, almost twenty-five years before Isotta died, has raised long discussions because of its epigraph with dedication "D. ISOTTAE ARIMINENSI B.M. / SACRUM MCCCL," read especially by certain nineteenth-century critics as a kind of blasphemy on account of that dotted D, an abbreviation for "Divae," "divine," and the B, believed by some to stand for "Beatae." It was as if Sigismondo had written "Consecrated in 1450 to the blessed memory of the divine Isotta of Rimini," as if his mistress, for such she was still at that time, were elevated to the rank of saints and blessed, without the lord of Rimini having been invested with any authority by the Church. In fact, the adjective "diva," should it be read that way (and not as an abbreviation of domina), was entirely appropriate to a lady of Isotta's rank. And the "B" would stand for bonae: "Consecrated in 1450 to the good memory of Mrs. Isotta of Rimini."

In any case, for the pope, the problem was certainly not the tomb. Nor probably was the Temple, since syncretism was not uncommon at the time, though not as abundant as in Sigismund's church. Still, the Temple was a good excuse to paint Sigismondo Malatesta as an ungodly lord, a blasphemous and evil ruler, a godless man. And so against that church, which looked more like a pagan temple than the home of the God of Christians, would be hurled in 1462 the tremendous judgment of Pope Pius II, who had already launched a most violent indictment against Sigismondo Malatesta the year before. Pius II was an ally of Ferdinand I of Aragon, who claimed conspicuous credit from Sigismondo. Sigismondo, however, was struggling to honor his debt: the pope called him back to his duties several times, but on Christmas Day 1460, given his continued disobedience, and given above all Pius II's desire to get rid of a valiant leader who had always created problems for the Papal States, he launched excommunication against him and his brother Dominic and, in a consistory convened on January 16, 1461, held a sort of trial in absentia during which terrible accusations were hurled against Sigismondo. The lord of Rimini was accused of being a heretic, a blasphemer, a murderer, and a uxoricide (the pope accused him of having killed his first two wives in order to be able to dissolve his marriage bonds), and of regularly committing theft, incest, rape, and violence even to children. And such a deviant personality could only have a temple built in his own image. In 1462 Pius II, in his Commentarii, painted the Malatesta Temple in these terms: Aedificavit tamen nobile templum Arimini in honorem divi Francisci, verum ita gentilibus operibus implevit, ut non tam Christianorum quam infidelium daemones adorantium templum esse videatur, "He had a noble temple built in Rimini dedicated to St. Francis, yet he filled it with pagan works, so that it looked like a temple not of Christians, but of infidels worshippers of devils."

Obviously, Sigismund was not a literal forward Satanist. The iconographic program of the building is the visual manifestation of the celebration of a power, of the philosophical culture of mid-fifteenth-century Rimini, of an ideology that intertwines the sacred with classical and neo-Platonic elements. Certainly, Sigismondo Malatesta had no intention of being disrespectful toward the Christian religion: not least because, if he had been, the Franciscan friars who administered worship inside the church would have been the first to scold the lord. Pius II's interpretation, however, was functional to his political design.

After launching his indictment, the pope cursed the lord of Rimini, condemned him to the fires of hell, dissolved his Rimini subjects from the bond of loyalty to the lord, and finally, in April 1462, revoked every honor given by the Church to Sigismondo, his relatives and descendants up to the fourth generation, and organized a sort of "mock execution" in several squares of Rome, during which effigies of Sigismondo Malatesta, portrayed life-size, were burned at the stake. Not satisfied with this, the pontiff, who fervently desired Sigismondo's downfall, also promoted a warlike action against the lord of Rimini: that same year, the papal army, led by the condottieri Ludovico Malvezzi and Pier Paolo Nardini, occupied the Cesano valley and marched toward Rimini. Sigismondo Malatesta went on the counterattack, defeated the papal army commanded by Napoleone Orsini at Castelleone di Suasa and occupied Senigallia, but during the summer he suffered a crushing defeat at the mouth of the Cesano River by his lifelong rival, Federico da Montefeltro, count of Urbino, an ally of the pope. In May 1463, the papal army recaptured Senigallia and also managed to drive Sigismondo out of Fano, a city that had been Malatesta for two centuries and became an ecclesiastical vicariate. Sigismondo had lost the war.

After the defeat, the Venetian Republic, Malatesta's longtime ally, pressured the pope not to rage against Sigismondo and Rimini: the lord, in order to avoid losing the city as well after the territories of his lordship had been drastically reduced after the war, asked for and obtained a papal pardon. Left isolated, fallen into economic ruin and with an image to be rehabilitated, he decided to take part, on behalf of Venice, in the expedition against the Turks in Morea, a difficult and extremely risky undertaking, in which no condottiere would have wanted to embark: Sigismondo thus returned to Rimini without having achieved the success he had hoped for. He then tried to obtain some benefit from Pius II's successor, Paul II, but in the end he succeeded only in retaining his city. And perhaps that was enough, the way he was reduced.

Sigismondo Malatesta died in 1468: that year would also see an end to the story of the Malatesta Temple. The building site, moreover, had already stopped at the time of the clashes with Pius II. No drawings or models remained of what it should have looked like when finished. But the grandeur it was supposed to emanate is evoked by the famous medal by Matteo de' Pasti, the only one of Sigismondo's artists to remain by the lord's side until the end. It is the only work we know of in which we can see the Temple as it should have been when finished: the upper register of the facade should have ended with a great round arch, connected to the lower register by two volutes that would have decorated the two triangular elevations. And at the bottom was to be a majestic rotunda crowned with a dome, similar to that of the Pantheon in Rome. The project never saw the light of day, and the Temple remained unfinished, like the dreams of the lord who had strongly desired it. A lord doomed by history, and rehabilitated only in recent times. His intelligence and glory, however, are eternalized in a Temple that bears his family name. With art, D'Annunzio would have written, "the great tyrant conquers time, far more alive than then when he ran the cities and provinces."