The first pc in history: the Olivetti Programma 101, an Italian masterpiece of engineering and design

Perhaps not everyone knows that the first personal computer in history is Italian: it is the Olivetti Programma 101, a masterpiece of engineering and design. It can be seen in a number of museums, including the Museum of Computing Instruments in Pisa.

By S. F. | 04/01/2025 14:09

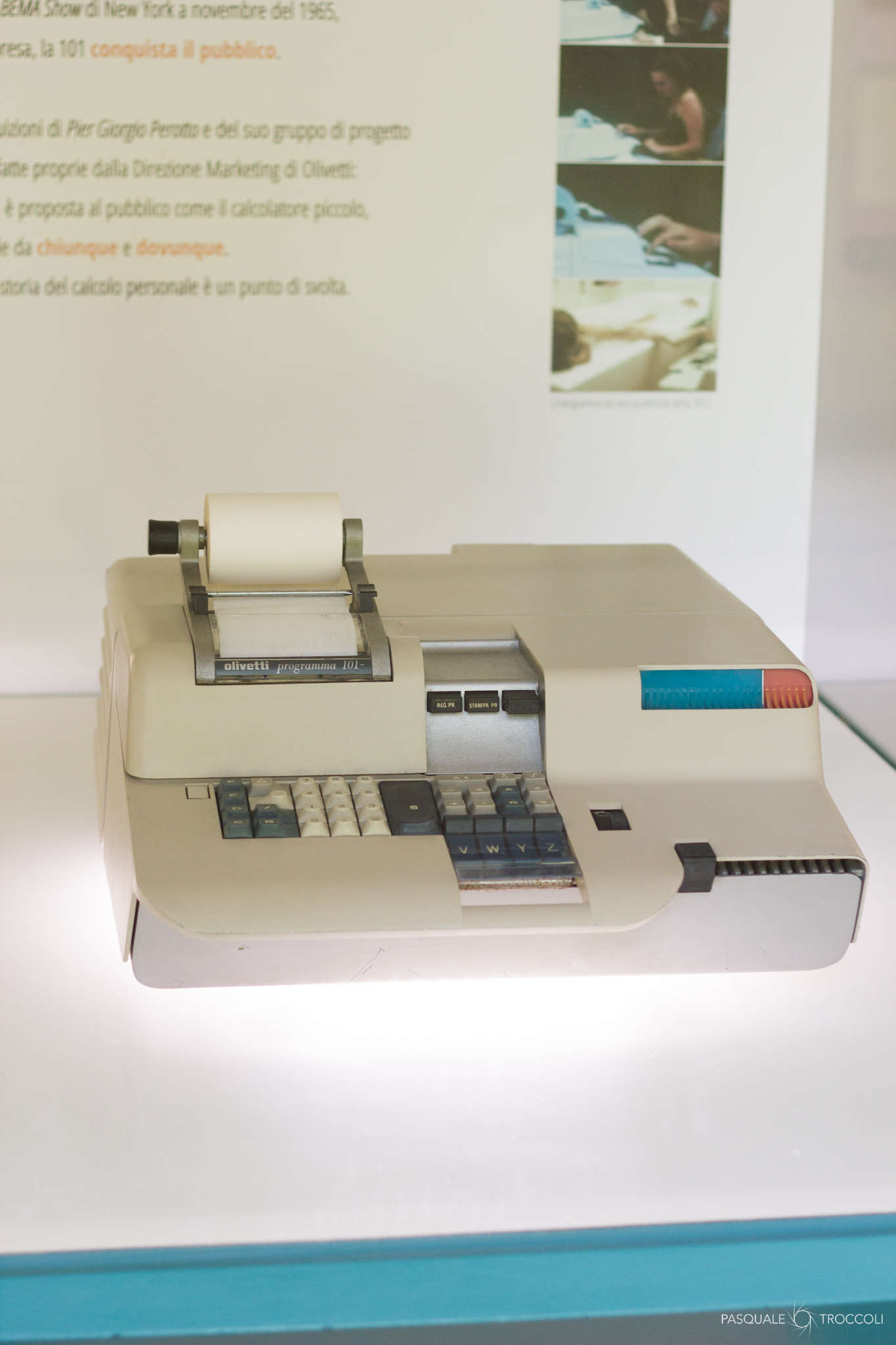

Among the display cases at the Museo degli Strumenti di Calcolo inPisa, one of the institutes of theUniversity of Pisa's Sistema Museale d'Ateneo , it is possible to come across an extraordinary relic from the history of computing, Olivetti's Programma 101 , a machine that marked an important moment in the path to today's computers, so much so that it is often found on display at museums dedicated to technology. The Olivetti Programma 101, also known as the P101, is a programmable desktop computer, also referred to as the Desktop Computer for this reason and even considered by many as the first personal computer in history.

Usually, when we think of the history of computing, we imagine it dominated by the names of U.S. companies such as IBM, Apple and Microsoft, and so it is easy to forget the fundamental contribution of an all-Italian company like Olivetti. With its Programma 101, the Ivrea-based company wrote an indelible page in the history of technology, creating a product that marked the history of computers. A portable computer, which was stored inside a case: when opened, an object appeared that, at the time, might have resembled the shape of a typewriter. But it was actually a computer, composed of three blocks: the electromechanical section, the electronic section and an electric motor, all equipped with a keyboard that acted on a mechanical encoder put into action by the motor. An instrument that might seem rudimentary to us today, but at the time it was as advanced as it gets, not least because of its all-Italian design, entrusted to Mario Bellini (Milan, Italy, 1935), one of the greatest designers in the history of our country, who was very young at the time when he envisioned the shape of the Programma 101. But what made the Programma 101 such an extraordinary innovation?

A revolutionary idea in the heart of Italy

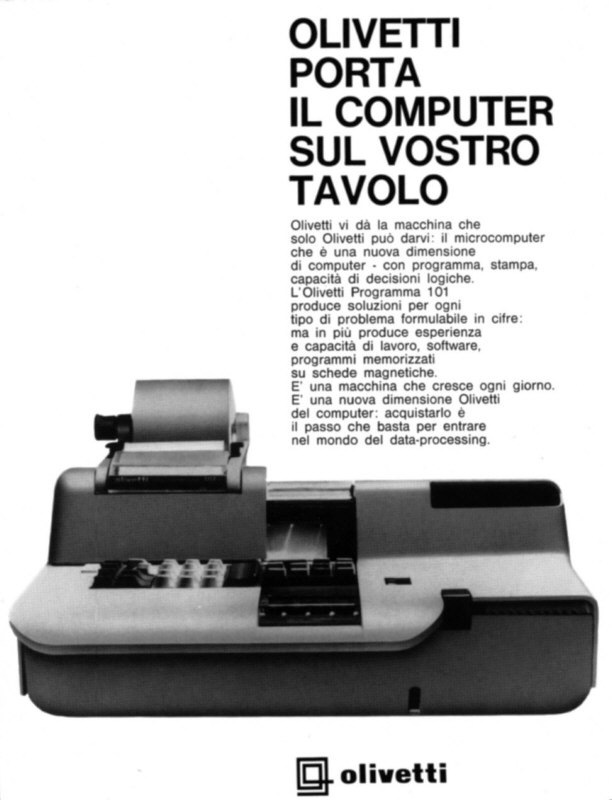

The Programma 101 was first unveiled to the public in 1965, during the BEMA trade show in New York, a kermesse for office products. Designed between 1962 and 1964 by a team led by Pier Giorgio Perotto (Turin, 1930 - Genoa, 2002), an Olivetti visionary engineer then in his early thirties, the machine (which was also called the "Perottina" because of its father's name) was designed to simplify data processing, meaning that it worked through simple instructions. At that time, in fact, computers were huge, expensive and difficult to use, reserved for large companies or academic institutions. In contrast, the company's CEO, Roberto Olivetti (Turin, 1928 - Rome, 1985), wanted a computer that was easy to use and inexpensive.

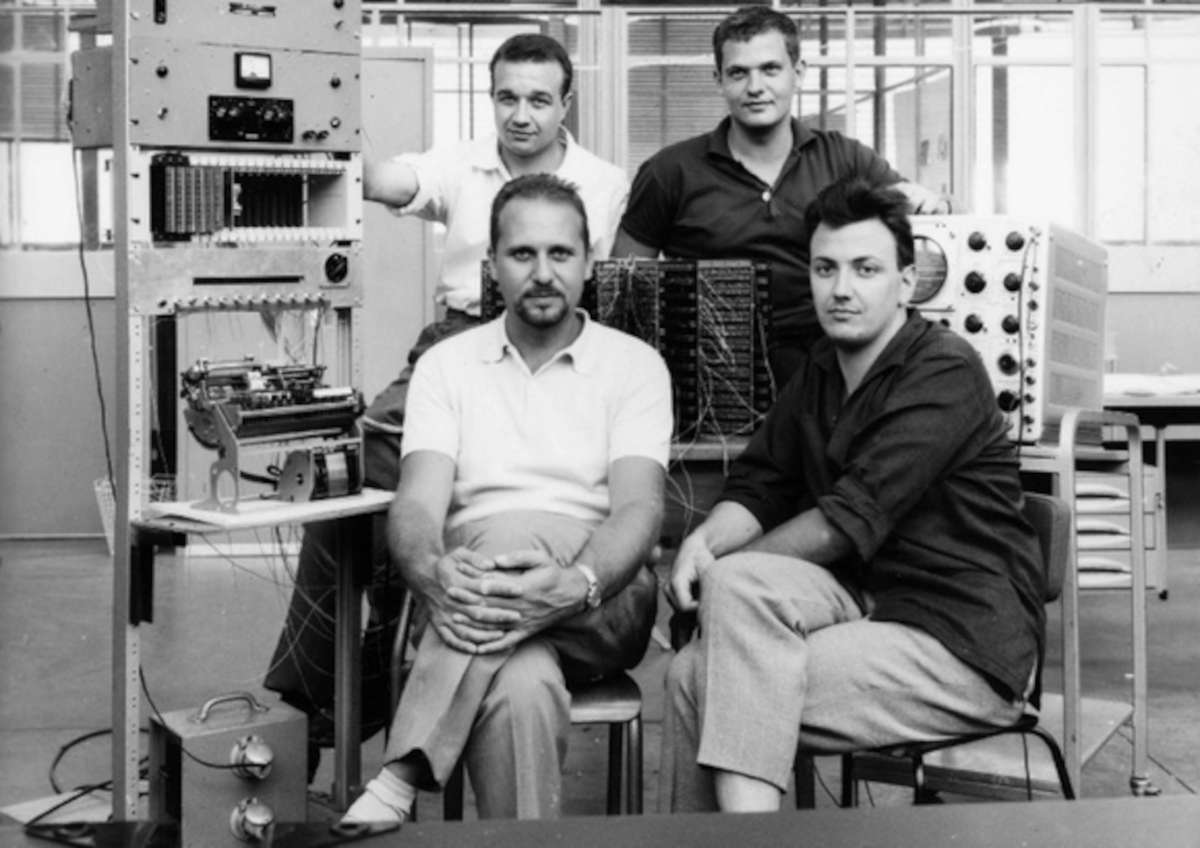

The idea of Perotto and his team, which included Giovanni De Sandre, Gastone Garziera, Giancarlo Toppi, and Giuliano Gaiti, was as simple as it was revolutionary: to create a compact, intuitive, and easy-to-use device that could be placed on a desk like a typewriter. The result was an elegantly designed programmable calculator that anticipated the very concept of the "personal computer" by several years.

The genesis of the P101 was not without its challenges. Perotto and his team faced technological, organizational and cultural obstacles. At a time when computers were seen as exclusively business or academic tools, convincing the company to invest in such an innovative and futuristic product was a daunting task. However, the support of Olivetti's management, which had already focused on innovation in the past with products such as the Lettera 22, allowed this ambitious project to go forward. "It came to take shape in my mind not so much a solution as a dream," Perotto later recounted in his book Program 101. The Invention of the Personal Computer: An Exciting Story Never Told (1995), "the dream of a machine in which not only speed or power were privileged, but rather functional autonomy, which was capable not only of performing complex calculations, but also of automatically managing the entire processing procedure, yet under direct human control. But the idea was not so much to envision total automatism as a friendly machine to which to delegate those operations that humans do poorly or are a source of mental fatigue and error, such as data entry and extraction and repetition of computational procedures." The P101, in essence, was to automate scientific calculations typical of subjects such as engineering, finance, geometry, and statistics, and it was to do so at a low cost to the companies that purchased it. We speak, after all, of a calculator in the original sense of the term, that is, a machine that, in the original meaning of the term "computer," merely made calculations.

Another key element in the birth of the P101 was the historical context. In the 1960s, Italy was experiencing a period of economic and cultural growth, the period of the Italian economic miracle. In this climate of optimism, Olivetti saw technology as an opportunity to consolidate its leading position in innovation. The genesis of the Programma 101, however, starts from afar: at least from April 1957, according to Perotto's own account, and from Pisa, where Olivetti had set up an advanced research laboratory in the field of electronics: it was in Pisa in April 1957 that Perotto began working for Olivetti, with the task of designing an electronic machine capable of converting punched tapes into cards to be fed into a computer that would process them. At the time, in fact, cards were the only material that machines could read.

Technical characteristics: an engineering masterpiece

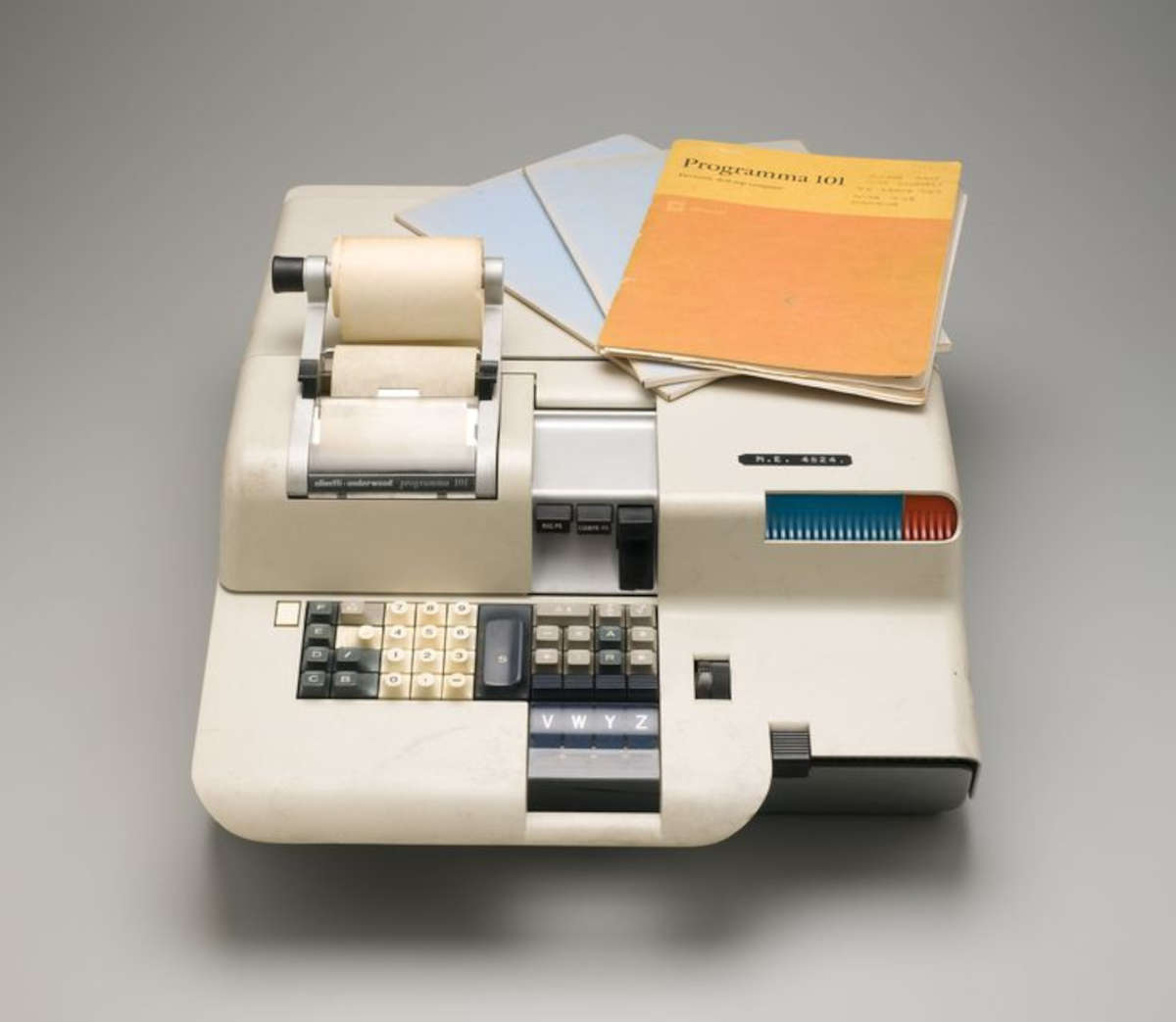

Functionally, the machine was equipped with a keyboard through which the user entered instructions, a printing unit that printed results over a strip of paper (at a speed of 30 characters per second), memory that contained data and instructions, thearithmetic unit , and the magnetic card reader-recorder . The P101 had ten memory registers: eight were used for data (they had a capacity of 22 digits, plus comma and sign, but these could be split in two to hold 16 numbers of 11 digits) and two for instructions (they could hold a program of 48 instructions, but this could be as large as 120 instructions if the units for instructions took up units normally reserved for data). Data and instructions were recorded on the magnetic card. There were 16 machine instructions in all: 5 were arithmetic instructions (addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and square root), 3 for transferring data from one register to another, 2 for printing, and logical instructions that allowed the machine to behave in a certain way in the presence of a given event (for example, in the event that a content was above or below zero). The machine could operate in two modes, manual and automatic. The manual mode was similar to that of a normal calculator, but the machine was able to record the user's operations, and in this case it was possible to set programs to run automatically: the only operation required of the user was to enter the data on which the P101 was to perform the calculations. The number of program instructions could be unlimited because the machine could use multiple magnetic cards in sequence.

In essence, with an intuitive interface, the machine allowed users to create programs without extensive knowledge of computer science. This language represented a radical simplification from the complex codes required by mainframes, thus bringing computer science closer to a wider audience. The built-in printing unit allowed results to be obtained on paper, an essential feature for offices: the ability to have immediate documentation of calculations represented an added value for professionals and companies.

The machine could perform complex mathematical calculations, handle data and solve logical problems, making it suitable for a variety of fields, from engineering to accounting. Its ability to adapt to different needs also made it a valuable tool in academic and scientific fields, as well as in disparate contexts, which surprised Perotto himself: for example, recounted the engineer again in his book, the Program 101 found use with tailors who used it to calculate the optimal way to cut fabric with minimal waste. Another striking aspect of the P101 was its ability to integrate into established environments. Users could use it in combination with other office tools, such as calculators and typewriters, thus creating a productivity-enhancing technology ecosystem. Those who wanted to try their hand at the P101 could use an online simulator designed by the University of Pisa.

The Program 101 was a success: marketed between 1965 and 1971, some 44,000 units were sold, mainly in the United States, where 90 percent of sales were concentrated (despite the difficulties of finding Olivetti technicians in the U.S. for any maintenance) and where the machine found use in areas such as space aeronautics (it was purchased by NASA )and defense. The P101 was even used for calculations related to the Apollo 11 mission, which took man to the moon in 1969.

The design: elegance and functionality

One of the most fascinating aspects of the P101 was its design, the result of collaboration between engineers and industrial designers, a hallmark of Olivetti. The understated, modern aesthetic was the work of Mario Bellini, a celebrated Italian designer, then at the start of his career. Bellini designed a machine weighing about 30 kilograms, with had dimensions comparable to those of a modern printer, making it much more compact than the mainframe computers of the time that took up entire walls.

Bellini had been called in after another great designer, Marco Zanuso (Milan, 1916 - 2001), had been removed from the job: in fact, Zanuso's design was deemed too bulky and complicated. Bellini, Perotto would later recount, "understood without difficulty the philosophy of the machine and agreed to study a solution that did not alter the logic and ergonomic setting that we had so thoroughly studied. The project was realized in prototype form in a short time. The subsequent show-down with Roberto Olivetti was not among the most pleasant experiences, but the very validity of the product and the success of the whole operation were at stake. I stated in no uncertain terms that no 'other solution was technically feasible and that the difficulties we still faced in solving all the reliability and manufacturability problems were such that it would be foolish to create unnecessary and absurd complications. In this way the Bellini solution passed."

Bellini devised a chassis made of profiled aluminum, a material chosen to avoid interference with electrical equipment, with elegant shapes, slightly curved at the corners as was fashionable at the time, and with uniform colors, and large, clearly visible keys. The P101 can also be found on display in some design museums today. The control panel included a keyboard to program the machine and display results. Everything was designed to be as ergonomic and intuitive as possible, in keeping with Olivetti's philosophy of combining technology and beauty. The design of the P101 was not just about aesthetics, however. Every element was designed to enhance the user experience. For example, the layout of keys and controls reflected a careful analysis of user needs, making the machine easy to learn and use even for those unfamiliar with calculators.

Another distinguishing feature was portability. Although the P101 was not really "portable" in the modern sense, its compactness represented a revolution compared to mainframes, which required entire rooms to house. This made it ideal for small offices and professionals on the move. However, the compactness was not a novelty in itself, since a number of "minicomputers" were already on the market in the early 1960s: however, these were still prohibitively expensive products, and in any case always bulkier than the P101.

An indelible legacy

The influence of the Program 101 is undeniable. Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs, founders of Apple, were inspired by the simplicity and design philosophy of the P101 for the design of the Apple I, their first computer. Many computer historians consider it the forerunner of the personal computer, an accolade that celebrates Italian ingenuity and Olivetti's boldness.

Today, examples of the P101 are displayed in museums around the world. The machine continues to be a symbol of innovation and a reminder of Italy's role in the history of technology.

In academia, the P101 is often used as a case study to analyze the evolution of computer technology and the importance of design in the creation of innovative products. The story of the Olivetti Programma 101 is thus an example of how vision and ingenuity can challenge the technological and cultural limitations of its time. At a time when information technology was still uncharted terrain, Italy was able to carve out a leading role for itself. The P101 is not just a machine; it is a monument to creative genius and innovation, a legacy that continues to inspire the world.

The Olivetti Program 101 is also an invitation to reflect on the value of innovation and the need to invest in bold ideas. The idea, in that case, was to create a machine that was not only the preserve of technicians and scientists, but could also be used by non-specialists. An advanced calculator that could rely on the use of ordinary people. "Unfortunately, in those years," Perotto would recall, "few companies and few designers cared about user problems and the ease and practicality of using machines. On the other hand, the technologies of the 1960s were still very limited, and the designers' main concern was all about the problems of pure and simple operation. It was man who had to adapt to the machine and not vice versa. Quantitative performance was demanded of computer electronics, lots of processing power, lots of memory capacity, high data printing speed, and nothing could be wasted on improving the relationship with man, who, moreover, was always a skilled technician. The technologies also showed an evolutionary trend toward increasing potential, but they did not provide much foothold for those who wanted to make the computer friendlier and easier to use." His idea of the personal computer would revolutionize history.