The Pietro Aldi Cultural Pole in Saturnia: a model of good musealization

In Saturnia, a hamlet of Manciano known for its spa tourism, a small museum dedicated to the Romantic painter Pietro Aldi was opened a few years ago: the museum combines a focus on the local area with the enhancement of the permanent collection.

By Jacopo Suggi | 28/12/2024 16:22

Italy is a land of museums: from North to South, passing through the islands, there are more than 4,000 (in some rankings even close to 5,000) museum institutions that open their doors to the public, thus bringing the Belpaese to be one of the nations with one of the richest cultural landscapes in the world. What's more, every third municipality sees a museum institution in its area, numbers that continue to grow if we consider that no less than a dozen new museums are popping up every year. These numbers in themselves, however, are not enough to immortalize a paradisiacal situation, and in fact, while the number of Italian museums continues to grow, there are still major problems regarding the management and preservation of the heritage, as well as its enjoyment, with services, including theremoval of architectural barriers and those of digitization, often still lagging culpably behind; to these and many others, add the fact that more than half of all visitors are concentrated in museums in only ten Italian cities. This last instance is perhaps the most worrisome because on the one hand it returns a phenomenon of congestion of tourist flows, and on the other it raises the question about a proliferation of museums whose visits stand at telephone prefix numbers, tying in with the further theme of the "short blanket." the opening of each new museum often makes the one next door contend for funding, and is hardly able to stand as an alternative to the most visited museum institutions, but if anything erodes audiences from smaller counterparts. The question that professionals in the field therefore often ask is whether it really still makes sense to open new museums. That question remains without a definitive answer, unless we settle for a laconic "it depends."

Indeed, it depends on many factors: first and foremost, whether the intentions of the new opening do not end at the opening alone, leaving the museum to live on in perpetual somnolence thereafter, but no less important is the need for the museum to see as its main (though not only) referent the community local, the institution that is instead created with the ambitious aim of opening up first and foremost to outsiders is more often than not doomed to fail in its goals, and see some attendance only on weekends. The museum can and should be the territory told and represented: this maxim seems to fit aptly for a relatively recently founded Tuscan institution, which from year to year advances its discourse, while at the same time increasing its reach. The Polo Culturale Pietro Aldi is located in Saturnia, certainly the most famous hamlet of the municipality of Manciano to which it belongs, in the province of Grosseto, a locality famous since Etruscan-Roman times for the presence of thermal waters. The Pietro Aldi Cultural Pole was born perhaps also with the intention of expanding the tourist offer of the area, monopolized by thermal tourism, becoming on the one hand a showcase of the area but also a reference point for the surrounding community.

It was established thanks to the far-sighted efforts of Banca Tema, heir to the former Banca di Credito Cooperativo di Saturnia, which in the late 1980s decided to purchase from the heirs a substantial nucleus of works by Manciano painter Pietro Aldi to prevent their dispersion. In 2016, following an architectural intervention aimed at re-functionalizing a bank building into a museum institution, the Pietro Aldi Cultural Center was born, which is located in the main square of the Maremma hamlet. The sober exterior structure of warm stone and brick gives way inside to a minimalist, contemporary space, where on the ground floor, in addition to the ticket office and bookshop and educational rooms, there is a library and a small exhibition space that promotes the area and its products. In contrast, the permanent collection, all centered on Pietro Aldi, unfolds on the second floor, where a modern layout breaks the monotony of the classic scanning of the rooms, resolved in straight lines and sharp angles, to create an organic and continuous path, studded with works hung on the walls or encased in elegant showcases.

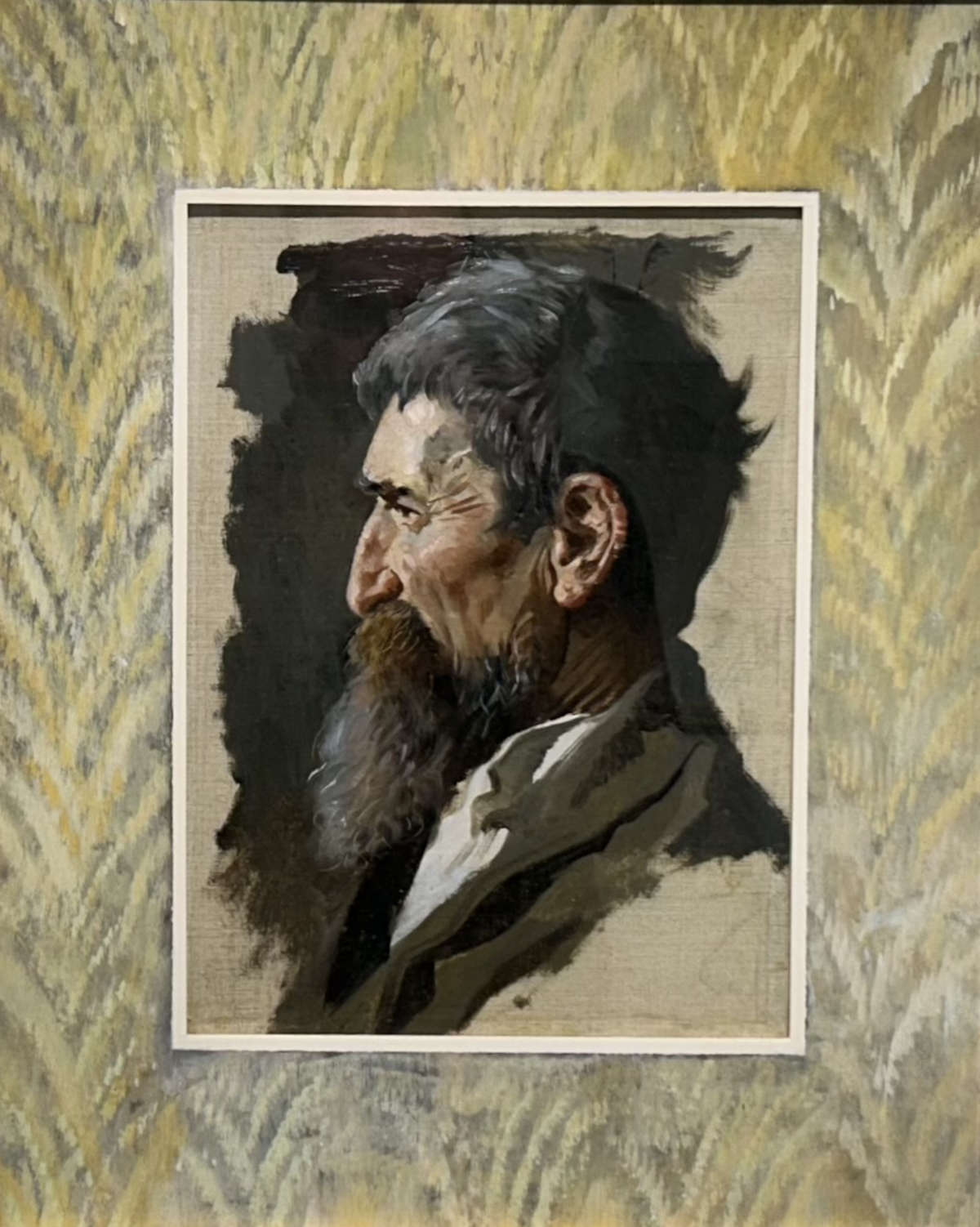

A visit to the museum restores the experience of life and in painting, which would otherwise risk being forgotten, of one of the most significant artists who was born in these lands. Pietro Aldi was born in 1852 in Manciano to a family of well-to-do landowners, who would have wanted their son to have a career in the church, which was soon disregarded in favor of an artistic education, marked by attendance at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Siena directed by the celebrated Luigi Mussini, a purist painter who gave life to a lively school brimming with talent. Under Mussini's aegis, Aldi remained for seven years. Bearing witness to this period are works of academic taste, such as the Study of a Male Nude, exhibited here, in which the painted figure, veined with a natural and measured beauty, and not magniloquent or idealized, betrays a conduct close to the purist dictates on the model of Ingres advocated by the master. With this work dating from 1873, Aldi won the annual competition of the Academy of the Nude, shortly marking the conclusion of his training in Siena.

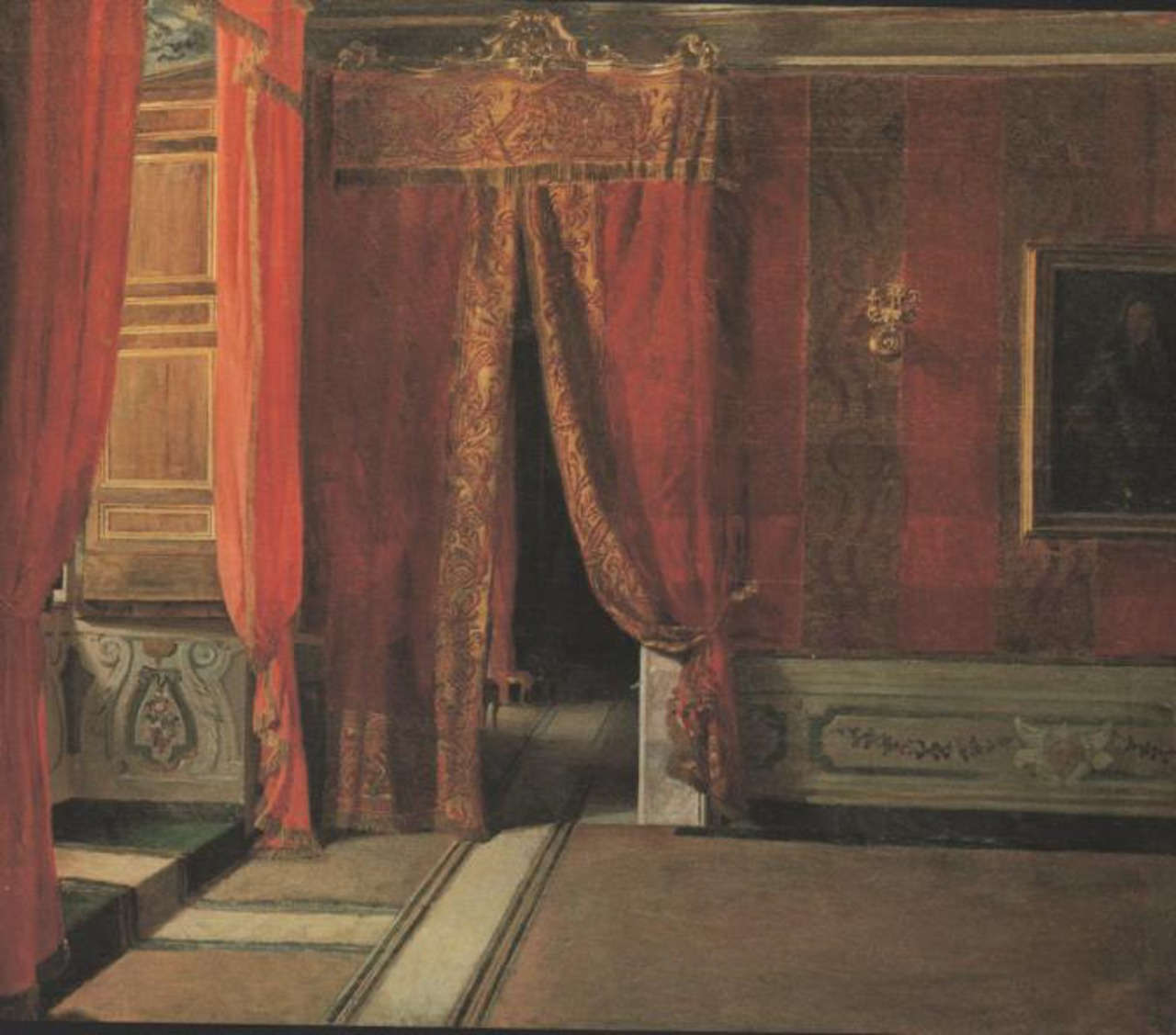

From just a couple of years earlier is Still Life with Fur and Lute, where Aldi paints an accumulation of textiles and drapes, animal furs and a Volterran celebe, while on the wall behind stands Perugino's self-portrait. These are objects employed by Mussini's school for academic exercises, and they also appear in other paintings of the period, while the effigy of the Umbrian artist testifies to how he was considered in the Romantic era to be among the great masters of the Renaissance.

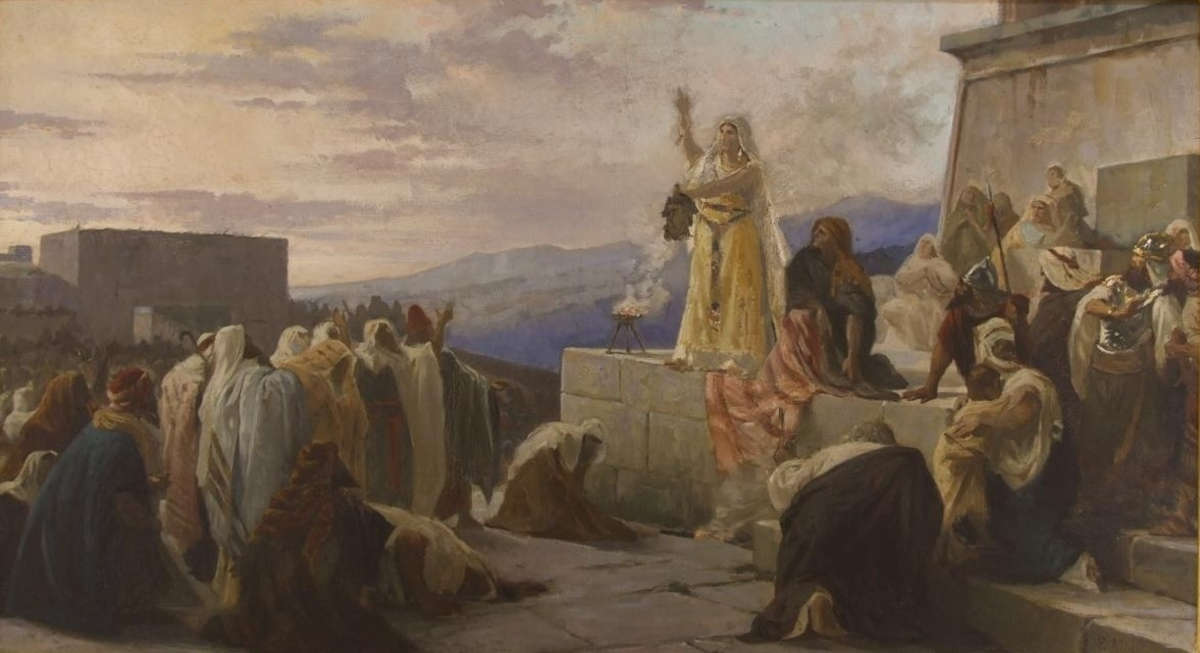

From these early trials, Aldi is distinguished by great virtuosity in the material rendering of textiles and wood fibers. The same talent can be detected in a triptych of works, but which were originally a unicum, later dismembered in later years by third parties to maximize profit in sales, where the interiors of the Palazzo Corsini at the Lungara in Rome are shown. Perhaps Aldi had come into contact with the Florentine-born nobles, as they had estates in Maremma, thus allowing the painter to depict the spaces of the sumptuous home before it was sold to the Italian state in 1883. Probably, these were notes that the Manciano artist counted on being able to reuse to set some paintings of historical themes, which along with those taken from literature, and religion, were the subjects most frequented by Romantic painters, and which in the Polo di Saturnia are reflected in works such as Agamemnon condemns Iphigenia to sacrifice or in the sketch The Meeting of Magdalene with Jesus.

The museum also holds the study of Buoso da Duera, a painting that exhibited in Rome at the 1878 Art Exhibition secured Pietro Aldi "an honorable place among Italian Painters," as Mussini recalled. This first great success is linked to a theme of great fortune among painters of the time: in fact, artists of the caliber of Enrico Pollastrini and Giacomo Di Chirico also measured themselves against it, and it narrates a medieval historical episode starring the leader of the Ghibelline faction, lord of Soncino and Cremona, who the chronicles want to betray his homeland, only to be driven out of it. The scene narrated in the historical novel The Battle of Benevento, by Francesco Domenico Guerrazzi, shows Buoso as a beggar recognized by his fellow citizens raising scandal.

Moving to Rome, though never cutting the umbilical cord with his homeland, to which he returned frequently, Aldi produced works such as La Fornarina sorpresa da Raffaello, in the museum represented by a sketch, which shows a taste for less committed and more intimate themes drawn from the biographies of great artists. With the death of Victor Emmanuel II, the City of Siena decided to honor the figure of the first king of Italy with a decorative cycle intended for the Palazzo Pubblico. Mussini was chosen for this undertaking, who, since he was elderly, wanted to involve his best pupils. It was on this occasion that Aldi produced his most famous works: for the Sala del Risorgimento he painted the king's meeting with Radetzky and the one in Teano with Garibaldi. To fulfill this commission Aldi carried out meticulous study work, producing numerous drawings, sketches and sketches, which are in the museum, such as a portrait of the king and a study from life of horses. The sketch L'incontro di Vignale shows the Manchurian's documentary confidence in tackling the work entrusted to him, so much so that although he accepted some of the commission's suggestions, he did not want to stick to the biography of the king written by Giuseppe Massari, who told how the historic meeting took place in the street and not in a farmhouse, but Aldi made his case as he claimed "I have had from person who was at that event a very detailed description of the same." Several preparatory works are also preserved of the Teano encounter, of which perhaps the most interesting is theSelf-Portrait in Profile. In fact, in the left margin of the composition, the painter decided to effigy himself, next to his master Luigi Mussini. The Aldi Pole's collection also includes numerous portraits of great quality: some move away from the finish and polish of the Academy, to offer a looser and fresher style, typical of Manciano's sketches, which bring him closer to some coeval research of Macchiaioli naturalism, as does the oblong canvas Figure along the walls.

The itinerary boasts many other works, making the Saturnia Polo the largest collection dedicated to Aldi, among which it is worth mentioning the canvas with Study for The Triumph of Judith, of which the finished work was presented in 1888 at theVatican Exhibition and won the gold medal, and is still preserved in the Vatican Museums. In the Saturnia canvas we see an inlay of portraits, necessary for the painter to essay color combinations, which earned in the finished work concordant critical acclaim for perfect harmony. That same year he was working on the painting The Feast of Nero, intended for the 1889 Paris World's Fair. Unfortunately, he did not complete the work, because in May of that year he died prematurely in his Manciano home at the age of only 36, leaving behind a staggering amount of work.

The activities of the Aldi Cultural Center, however, are not limited only to the enhancement of the permanent collection, but also make use of temporary exhibitions, which are organized in the basement, and also promote some outside the exhibition space, such as the Pietro Aldi Pittore exhibition, which in 2019 saw the Manciano artist's works exhibited in Florence, bringing the figure of the artist to be known by a wider audience.

Thanks to these worthy initiatives, the focus of the dialogue with the local community, which is also based on careful educational activities aimed at all ages, and numerous other initiatives, the Aldi Cultural Pole of Saturnia stands as a successful model of a museum institution, which, despite not being able to count on high-sounding names, carries out its aims with seriousness, professionalism, and a continuous will to want to improve.