Masterpieces of the Flemish world at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium

From van der Weyden to Bosch, via Bruegel and Rubens to Magritte: the Royal Museums of Belgium offer an incredible immersion in the pictorial wonders of the Flemish school.

By Jacopo Suggi | 19/11/2024 18:53

Brussels is said to be a capital city to which its own state goes, wanting to emphasize the city's imposing scale in size and population in the context of a relatively small country. The same cliché might also marry for its Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium (Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, or Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten van België), if one did not keep in mind, however, that in spite of its size, Belgium is a giant of painting, capable of making a fundamental contribution to several seasons of art history. This wealth is reflected in a museum system of the highest caliber, which finds its spearhead in Brussels in the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium. At the beginning of the 2000s, this extraordinary apparatus was reorganized and is now organized into several departments, which have recently undergone rearrangement again: for this reason some of them remain closed to the public at present.

The different realities are developed into four large collections: theOld Masters Museum, the Fin-de-Siècle Museum, the Modern Museum, and the Magrittemuseum, and two smaller museums dedicated to two artists, which are the Wiertzmuseum and the Constantin Meuniermuseum. While the latter are located in different parts of the city, the four collections find space in locations close to each other in the heart of the Belgian capital, on Coudenberg Hill, also known as the Royal Quarter, because it is precisely home to the Royal Palace and Kings' Square, as well as other institutional buildings. Currently, the Fin-de-Siècle Museum and the Modern Museum remain closed for refurbishment, but their collections are partly displayed by organizing some important exhibitions. If, in general, the closure of the two museums may generate sorrow, rejoice the visitor who is generously deprived of a very difficult choice, because in themselves the Old Master Museum and the Magritte Museum are two institutions that the tourist cannot hope to exhaust even in numerous visits.

Although the collections have quite different histories, the origins of the Royal Museum are owed to the frisson that spread during Napoleon's rule over Europe, driven by the Enlightenment vision of giving birth to encyclopedic museums that could worthily enclose within a walled perimeter all the manifestations of art deemed most interesting. Opened in 1803, after occupying some temporary venues, the museum found its permanent place in the imposing Palais des Beaux-Arts, in classical style, built by Alphonse Balat around 1880.

Still housed in this gigantic structure is the Old Masters Museum, an endless collection of extraordinary masterpieces of Flemish and European history, ranging from the 15th to the 18th century. It is a rich selection of paintings, making any attempt to offer an exhaustive overview of the entire museum arduous. The colors of each section identify the different schools and historical periods; obviously the most important and interesting corpus is the artists of the Flemish school, whose most significant protagonists and entire parabola are represented. A spectacular parade of masterpieces exhibits the Flemish primitives, between unknown masters and the great masters who constituted the glory of this school.

Superlative is a flap from a polyptych dismembered and scattered across half of Europe, depicting the prophet Jeremiah, while on the back is historiated Noli me tangere, by the mysterious Master of the Annunciation, believed to be one of the highest representatives of 15th-century Provençal painting, but also strongly influenced by Flemish and Burgundian tendencies. The motionless and austere plasticity of the prophet, depicted inside the niche with attributes and elements of his activity, calls to mind later solutions taken up by Antonello da Messina.

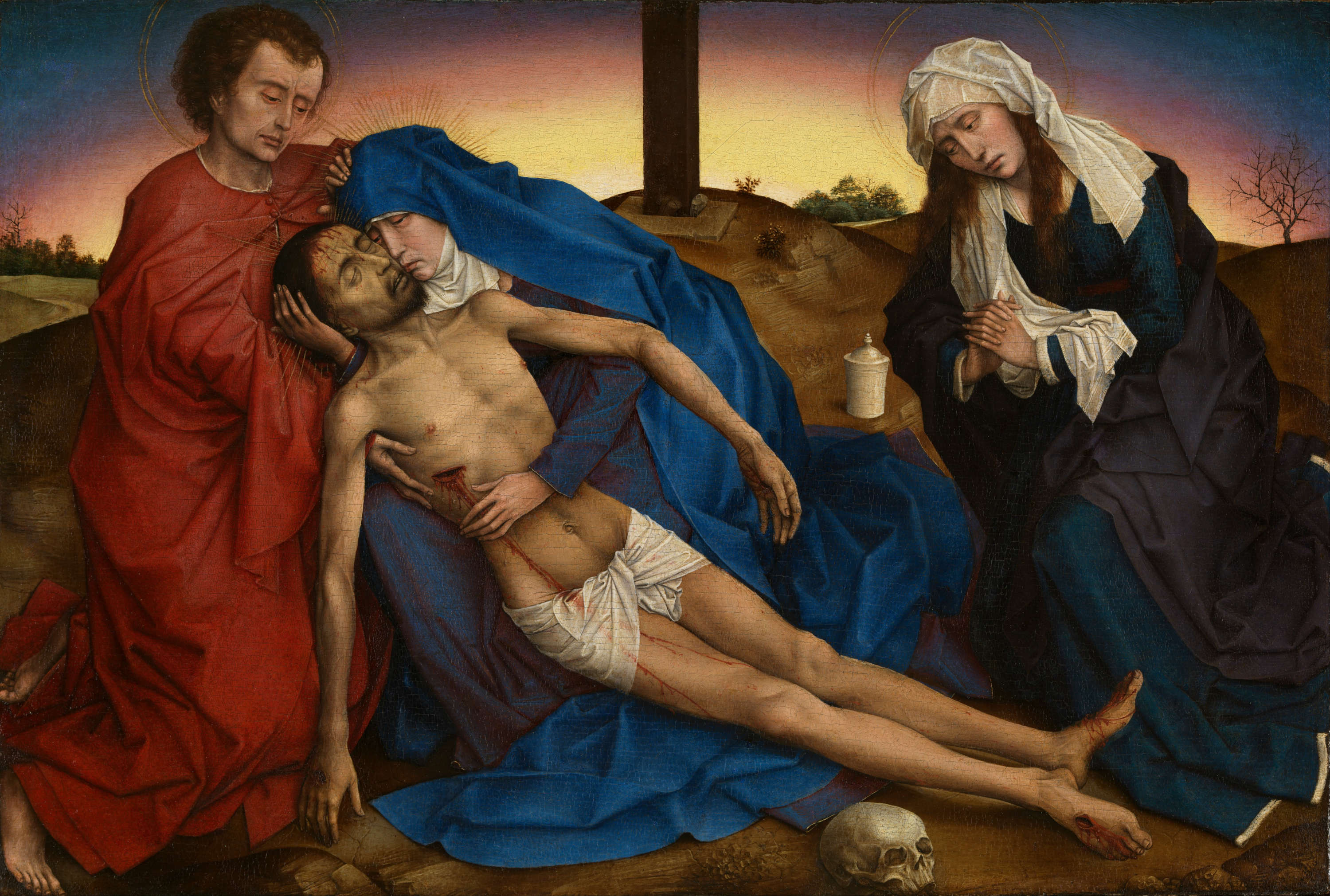

By one of the early great initiators of Flemish painting, Rogier van der Weyden, a number of religious works, such as the Pietà and the Sforza Triptych, and portraiture of superlative quality, including the portrait of Charles the Bold, the portrait of Laurent Froimont, and that of Anthony of Burgundy, are exhibited. These are paintings that show the painter's boundless ability to fully modulate volumes and place them in space, to probe emotional temperatures through lenticular rendering and by founding a new iconography in the secular poses of portraiture. Of the other pioneers of Flemish painting Jan van Eyck and Robert Campin a few pieces are exhibited but with dubious attributions.

Of the artists of the next generation, mention should at least be made of a Lamentation by Petrus Christus, a work that reflects the influence of Rogier van der Weyden's Deposition of the Cross, now in the Prado, purged, however, of the more drama to favor instead a quiet sense of contemplation suggested by the figures moving through a rural space, which transforms Jerusalem into a Flemish town; and the diptych with The Justice of Emperor Otto, a great masterpiece by Dieric Bouts, where lanky figures adorned in sumptuous robes show a greening of the characters of the International Gothic. Also of the two most significant artists of the late 15th century, Hugo Van der Goes and Hans Memling, sumptuous works are on display, in which the most calligraphic drawing emerges, almost like a kind of continuous arabesque, and colors of dazzling brilliance.

But the visitor who walks through the halls only in search of the famous signature would here, more than in other museums, make a fatal mistake, for even artists whose names remain unknown produced masterpieces of the highest caliber, such as the painting Virgo inter virgines by the Master of the Legend of St. Lucy or the Master of the Life of Joseph author of the Zierikzee Triptych in which the eburnean depictions of Philip the Fair and Joan the Mad appear.

Before we encounter the further developments of this successful school, we find pieces by painters also from the German school, many of whom trained and worked in the Flemish area. The highest achievements are those attained by the two Lucas Cranachs, father and son, in particular of the Elder, masterpieces such as Adam and Eve and Apollo and Diana are exhibited, in which we see that extremes of fluid linealism aimed at the search for an elegant and harmonious rendering. As the century turned, artists in this part of the world began to incorporate models and solutions inferred from Italian art into their canvases.

A prominent role among them is played by Gérard David, among the leading exponents of the Brugge School, whoseAdoration of the Magi, based on a scene crowded with figures inhabiting a space created with great perspective rigor and sensitivity to luministic data, while the figures are cloaked in monumental ambition, is on display in the museum. Also of great value are the works of Quentin Metsys (or Massys) where plasticity blends seamlessly with calligraphy and linearity. But the two geniuses who stand out for their originality in the 16th century and whose lesson had immeasurable repercussions for Flemish painting are Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel, both of whom are in the museum. The former, whose parabola began in the previous century and ended in the early decades of the 16th century, is represented by a Crucifixion with Donor, a work of refined brilliance and a workshop copy of the famous Triptych of the Temptations of St. Anthony, housed in the National Museum of Ancient Art in Lisbon. It was from the Dutch master that Bruegel the Elder derived his biting satire and taste for the grotesque, and in Brussels he is represented by an entire room, a true jewel of the museum. Caricatured and dreamlike is the Fall of the Rebel Angels, while works such as the Fall of Icarus, theAdoration of the Magi and the Census of Bethlehem show that persuasive malia of his landscapes, bathed in musical poetry, where an awkward and fragile humanity, far from any idealization, is staged. Still long is the list of great names in Flemish painting that opens before our eyes, demonstrating the importance of this fruitful school.

The other pinnacle of the collection, however, is the painting of the 17th century, demonstrating how the greatness of Flemish art did not end with the passing of the centuries. And it is particularly the large red room all dedicated to Rubens that takes the breath away from any visitor in an experience that is almost dizzying. On display here are numerous masterpieces by the Antwerp genius, one of the fathers of the European Baroque. The soft, tepid flesh that has emerged from Rubens's brush protrudes from the large canvases, laid out with his signature grandeur, enhanced by exquisite colors that become brighter and more imaginative when they depict triumphs or more calibrated and dramatic when they urge recollection and pathos. The rushing swirl of cloths and poses and the terse mist that occupies the sky, opening only from time to time to let through the translucent glow of God, transform the sacred tale into a'mythical epic, as in the Martyrdom of St. Lievin, the Ascent to Calvary or the painting The Intercession of the Virgin and St. Francis Stops the Divine Lightning; at the opposite end are compositions such as theAdoration of the Magi where a domestic quiet is not interrupted even by the crowding of numerous onlookers.

And how many incredible adventures does this museum still have to offer for the eye that has arrived at this point is not yet satiated, how many journeys, misplacements and rediscoveries do these sumptuous collections offer, among the austere and aristocratic figures chiseled by the sure hand of Antoon van Dyck, the psychological connections that betray the eyes of Rembrandt's portraits, and the opulence that overflows from Jacob Jordaens' canvases. The names and masterpieces are endless, and there remains room for the French such as Philippe de Champaigne, Simon Vouet, Lorrain, and others, but also for the Italians Annibale Carracci, Mattia Preti, Tintoretto, Crivelli, and Barrocci, to name a few.

But there is at least one last masterpiece that cannot be glossed over, whose iconicity makes it one of the most well-known and celebrated works in art history: The Death of Marat painted by Jacques-Louis David in 1793. After seeing the sacred theme treated with unparalleled grandeur, it is astonishing to see how David managed to transfuse the same intensity to transform a hero of the French Revolution, into a martyred saint. In a scene largely occupied by a gloomy background, the white body of the lifeless French politician emerges. The fledgling Christ is caught with an abandoned arm that harkens back to that of some famous Depositions, while the basin becomes his tomb as well as the sheet, which originally served to keep the heat of the water from dispersing, acts as a shroud stained with blood leaking from a wound on his side.

At this point, the visitor might consider himself sufficiently satisfied and abandon all other cultural endeavors, preserving his energy for the next day, but should he be a relentless and greedy culture-goer, he should know that barely a corridor and an elevator separate him from the most substantial collection of works by René Magritte, collected precisely in the Magritte Museum. This monographic museum arranged in the neoclassical building of the Hôtel du Lotto is the perfect crowning glory for in-depth understanding of the last offshoots of Flemish art, albeit lingering in the 19th century.

In fact, although René François Ghislain Magritte was born in 1898 in Lessines, in the Walloon part of Belgium, living and working, however, in Brussels, he made himself heir with his art to those ironic and morbid peculiarities of Flemish painting founded on attention to the mimetic rendering of the real. The foundation of the Magritte Museum is rather recent, dating back to 2009 in fact, when thanks to a far-sighted policy capable of attracting donations and deposits of important works, a reality capable of describing the entire career of Belgium's most famous surrealist was established and became a much-visited institution. The museum is spread over three floors, from the highest to the lowest, and exhibits more than 150 paintings, drawings, letters, sculptures and objects.

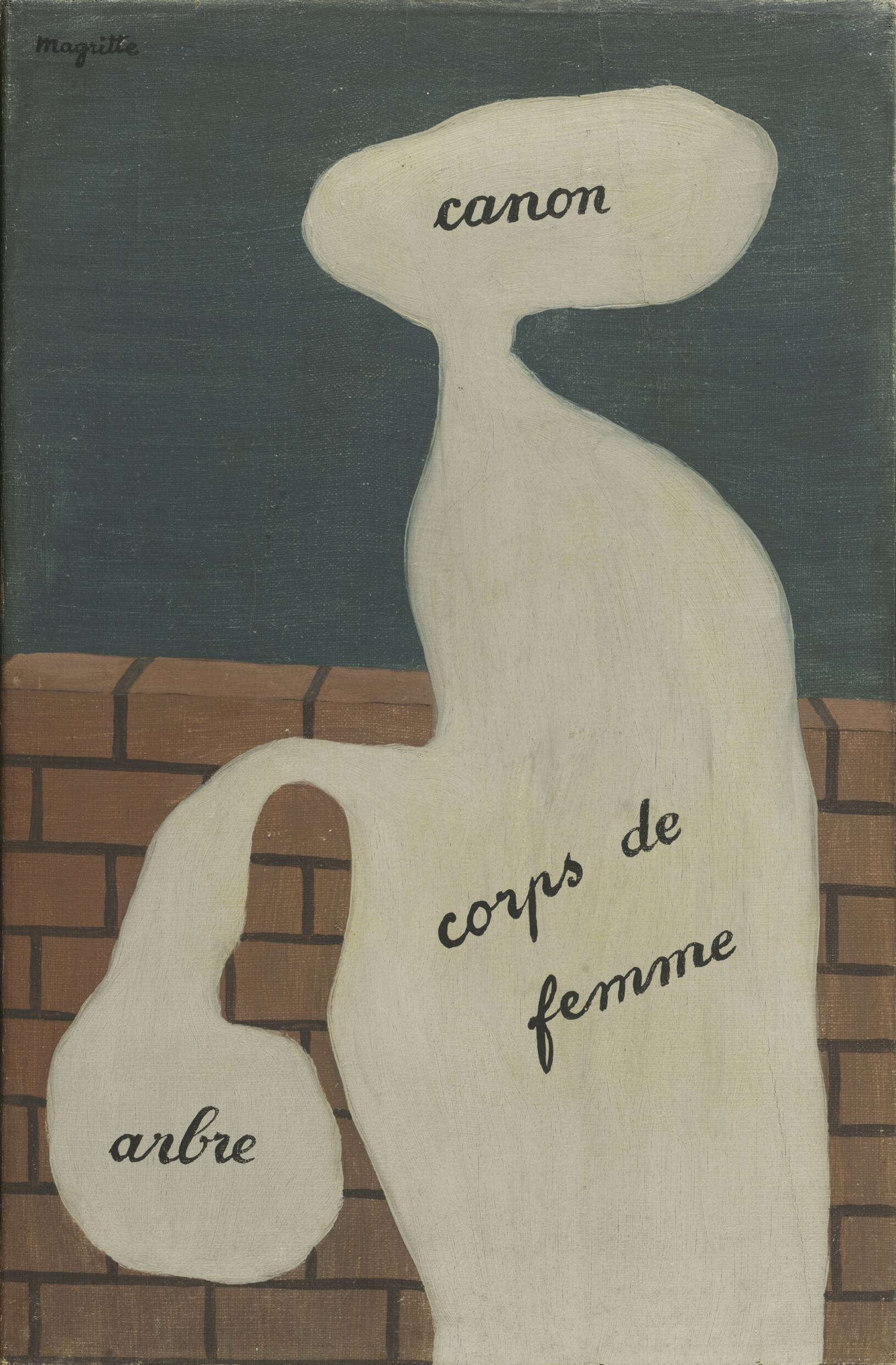

The exhibition testifies to Magritte's beginnings in the field of art far from that best-known production, and close instead to the artistic ideals promoted by the magazine 7 Arts, the Belgian counterpart of De Stijl, where trends in geometric and plastic abstractionism were promoted. These are paintings poised between futurist and constructivist suggestions, with a squillant palette, but of no particular originality. The tour then continues with advertising drawings in the cubo-futurist taste that the artist made to make ends meet during the 1920s. The impluvio in Magritte's art occurs with the encounter of Giorgio de Chirico's work, Song of Love, which shows the Belgian the compositional and imaginative possibilities allowed by figurative art. That moment also marks his rapprochement with the Surrealist cohort headed by André Breton, but still maintaining an independent poetics, in which randomness is limited, and where we see instead the evocation of rational absurdity. Thus the artist abandons formal abstract art although he will constantly make use of abstraction, not in its aesthetic, but conceptual dimension, isolating details from their concrete reality and lowering them into dreamlike contexts.

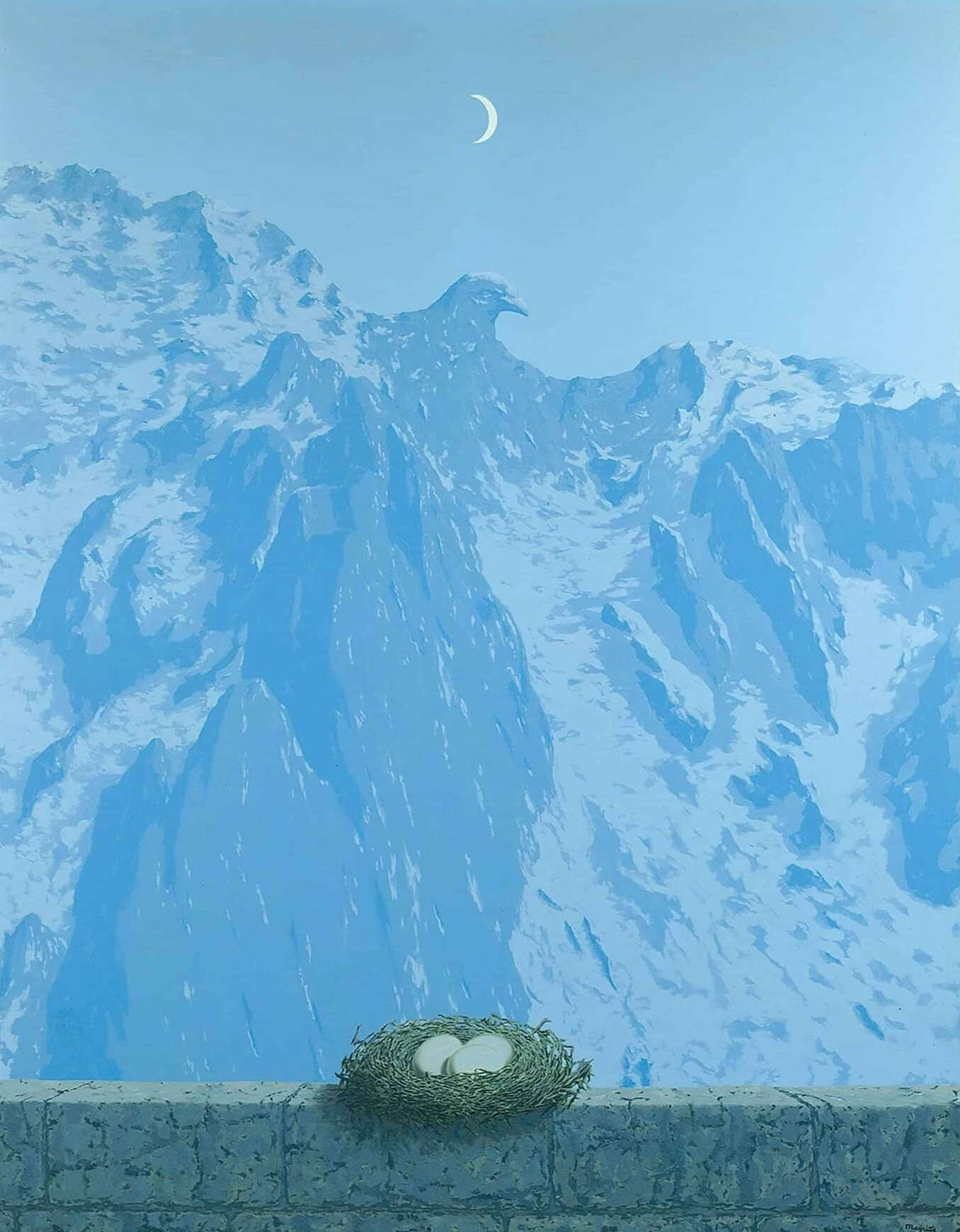

The museum makes it possible to delve through numerous works, displayed in rotation in the dark exhibition halls, into the multiple aspects of his art, among all the use of detail as a way of investigating and subverting order in its objective dimension, subjecting it to constant systematic doubt, fueled by paradoxical atmospheres and enigmatic titles, often chosen in complete randomness with the sole intention of disorienting the viewer.

But it also denotes his conception of an organic dimension of reality, which reverberates in works such as Blood of the World, where nature is shot through with inexpressible and elusive mystery. The contamination between depiction and words, perhaps a legacy of his involvement as a graphic designer in advertising, is also another pillar on which his art rests, as in L'usage de la parole, or the even more famous The Betrayal of Images (Ceci n'est pas une pipe), displayed here through graphics and drawings. But the museum also shows lesser-known productions, such as the period known as vache, in which the images become more grotesque, with immoderate colors and jagged drawing.

Finally, the visit concludes with a section that focuses on the concept of seriality in the Magrittian corpus, which was well disposed to repeat its best-known works in details or whole, even bringing them back in different media to pander to the market. At the end of the day, the visitor will come away overwrought but with the confidence of having embraced with his or her eye all the greatest artistic wonders of the Flemish world.