In the village of Trebiano Magra, where according to legend the manuscript of the Divine Comedy is hidden.

Trebiano Magra is a village of only a few inhabitants in Levante Ligure, but it is rich in interesting works of art and has many stories to tell. According to one legend, the manuscript of Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy is hidden in its castle...

By Federico Giannini | 11/08/2024 15:56

As soon as one walks down the alleys of Trebiano Magra, the silence is interrupted here and there only by the occasional meow. There is calm everywhere, even if summer is in its prime, even if it is morning and the Val di Magra sun has not yet begun to toast the caruggi paved with terracotta and stone, even if the second homes that for two months of the year enliven this village are already inhabited the second houses that for two months of the year enliven this village clinging to the slope of a hill, impossible to travel by any means other than one's own legs, a tangle of medieval houses with facades tinted in pastel colors. Summer is the season when Trebiano Magra awakens from its torpor, yet it seems that the village is populated more by cats than by humans. Some, perhaps more accustomed to the presence of humans, allow themselves to be approached, and then go back to sleep once they have ascertained the peaceful intentions of those who attempt an approach. Others, however, are more wary and disappear by jumping over dry stone walls. Here are four of them all together, lying down to rest: they are there, motionless but watchful, and they look as if they would not budge an inch even if it rained wetsuits of hungry dogs on these roofs. It would be all too easy to call them the "guardians of the hamlet": when there is a hamlet and there are cats, for the narratives of tourist brochures, cats are always the guardians of the hamlet. Except that the cats that populate the villages of Liguria have no desire to do anything, let alone have the slightest intention of guarding anything. The most they can do is offer you a listless, sleepy welcome as soon as you arrive.

And that would also be a fair and proper gratification for the traveler who has taken the trouble to go up to Trebiano, because you don't get here by accident. Trebiano is not a place of passage. One has to want to go there. Even the sign indicating the road to the village, the one that climbs up starting from Romito Magra, doesn't seem to have much desire to show itself. Faded, attached to the facade of a house on the provincial road, almost hidden after the traffic circle from which the road to Lerici starts. The road to Trebiano begins here. Three kilometers of asphalt that mount amidst olive trees, with hairpin bends that open every now and then to give unexpected views of the Gulf of Poets. A crooked road that leads to the small square where Trebiano's only church stands, that of San Michele Arcangelo, built outside the layout of the village.

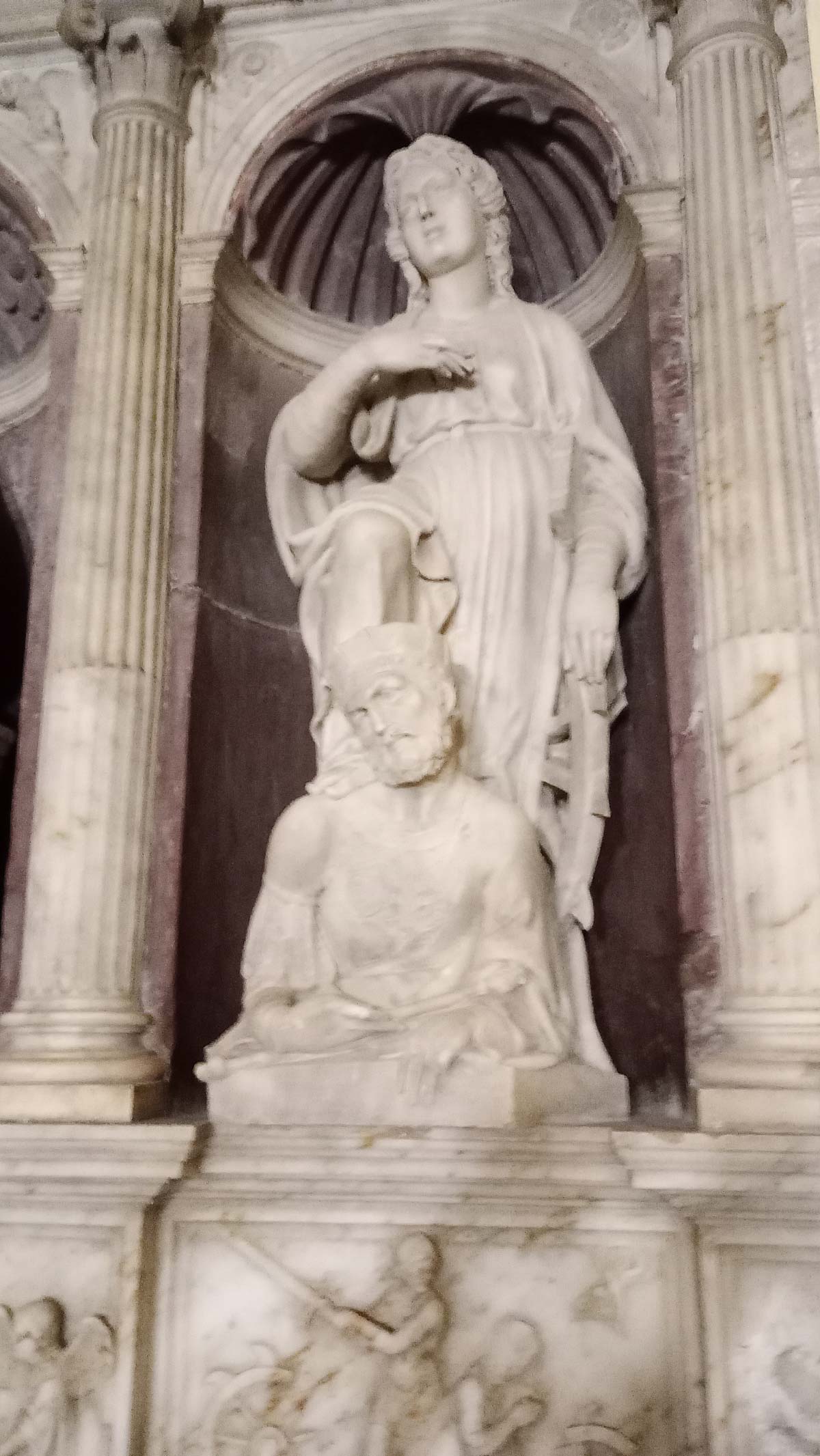

The parish church, of which there are records as far back as the 12th century, has a rather elaborate Baroque facade, with two volutes connecting the pediment to the lower register, and with an elegant broken tympanum housing the statue of St. Michael. The interior, with three naves, is filled with works of art. In a chapel opening on the right, one notices an altar at the center of which stands a wooden statue of St. Roch, flanked by those of two other saints, towering above a structure that covers a valuable cycle of frescoed saints from the 17th century, but perhaps something earlier. The Saint Roch is a work executed in 1524 by Domenico Gar, a French sculptor who, from the Marne Valley in northern France, had ended up in these parts at a very young age following his father Desiderio, who worked between Carrara and Pietrasanta. The Saint Roch of Trebiano is, at the present state of knowledge, the earliest known work by this artist: a work that, for the local community, moreover, is of mica secondary importance, since Saint Roch is the patron saint of Trebiano. Inside the parish church, near the door to the sacristy, is a stone on which village tradition has it that the saint rested his foot as he passed this way as a pilgrim. St. Roch must have been the only person in human history to have happened upon Trebiano for no apparent reason. In any case, Domenico Gar's statue must have appealed greatly to the villagers, since that same year one of the most prominent citizens of nearby Sarzana, Jacopo Mascardi, commissioned the "francesino," as his contemporaries called him, a marble triptych that was to be "pulchritudinis et bonitatis ad similitudinem et comparationem imaginis Sancti Rochi lignei existentis in ecclesia seu plebe Sancti Michaellis de Trebiano." That is, of comparable beauty and quality to that of the wooden statue existing in the church of San Michele di Trebiano. Domenico Gar had depicted Saint Roch with the unusual iconographic element of the angel healing the wound on his leg. And even in the triptych for the Mascardi he had shown himself willing to revisit traditional iconographies: in his marble work, a Madonna and Child flanked by Saints Bernard and Catherine of Alexandria, Catherine is seen caught in the unusual act of subduing the Roman emperor Maximian, under whom the saint had suffered her martyrdom. Domenico Gar kept to his commitment and within five years delivered to his patrons a work of great quality, which shows how he had left behind his transalpine legacies and was well within the context of 16th-century Tuscan sculpture.

After trying to understand something, striving to look beyond the obscene reflective glass, of the 15th-century painted cross (from 1456, to be precise, and executed by an anonymous painter "probably of Adriatic culture," Piero Donati hypothesizes, "and in any case foreign to the Tuscan and Ligurian area." since we do not know who he is, neither can we know how one of his works ended up here), we will note the presence of another coeval cross, which in the seventeenth century underwent an authentic addition: in 1634 a painter originally from Versilia, Filippo Martelli, painted four panels around it. Today, the little that can be admired of the original cross can be glimpsed from the oval in the center of the curious composition that was commissioned from Martelli for the very purpose of preserving the cross. Historical echoes: a two-century-old work, which was not supposed to be in very good shape, gained new life. Somewhat like the marble holy water stoup on the other side of the church, a work of reuse in the most appropriate sense of the term, since it was carved from Roman-era marble that perhaps composed an ancient votive altar. Many have tried, unsuccessfully, to decipher the ancient inscriptions that can still be read on the marble.

The village of Trebiano begins beyond the church, beyond the square with the plane trees, beyond an ancient pointed archway between what were once the walls of the village: what was once the gateway to Trebiano is now a house, a private residence. Trebiano is mentioned for the first time in a document from 963, but the origins of the settlement are perhaps even older, and the toponym itself is supposed to refer to the funds of a Roman family, Gens Trebia, which had estates in the area. Beyond the gate, two roads start: one goes up, the other down. The one going up is the Middle Street, the main street of Trebiano. Slate portals, cascades of bougainvillea, wooden shutters and feline presences alternate seamlessly until they lead the visitor to a staircase that turns abruptly in the opposite direction and leads to a higher level. Indeed, it seems that the village was built on terraces clinging to the hillside, all one on top of the other, and the houses are arranged on either side of these narrow streets that run the length of them. And every so often, narrow stairways open up in the middle of the street, making their way through the buildings and offering the visitor short, steep shortcuts to access the upper level. Other times, however, the alleys widen and, quite unexpectedly, behind a building, beyond a building, after an opening, appear small squares, loggias, balconies that offer refreshing, spectacular views of the Magra plain: the gaze lingers on the sinuous course of the river that flows into the Ligurian Sea, on the sharp profile of the Apuan Alps silhouetted on the left, on the towns that dot the coast, on the offshoots of the Caprione promontory that divides the Magra valley from the sea. Were we to listen to Simone de Beauvoir, these views are like prizes. Prizes that Trebiano magnanimously bestows on its guests in recognition of having come this far.

Simone used to come here to visit her sister, Hélène de Beauvoir, the painter, who is occasionally honored in the area with some exhibition reminiscent of her Ligurian sojourn. And Trebiano must have impressed her, since Simone mentions it in her autobiography Tout compte fait. "What a reward to find myself with my sister sitting on a terrace overlooking the countryside and the sea! I would not have enjoyed so well the stillness, the silence, the sound of the ice cubes in the glass, had it not been for this day of toil behind me. I dined and slept with the happy knowledge of a task well accomplished. All morning I walked with my sister through steep streets, between white walls: this village, still ignored by tourists, is inhabited only by peasants: so must have been Èze and Saint-Paul-de-Vence in the old days." The truth, however, is that few peasants were to be seen here at that time, since Trebiano "was a village of workers with a strong communist and anarchist political identity who, having finished their work in the factory, tended the field or vegetable garden." this is the reconstruction, less poetic but more faithful to reality, rendered by Umberto Roffo, a poet very much in love with Trebiano, to Marco Ferrari for his book Mare verticale, all dedicated to that stretch of eastern Liguria from Cinque Terre to Bocca di Magra.

Hélène de Beauvoir had found her Italian Provence here, had found in Trebiano the sunshine she would later pour into her paintings. She lived in the Middle Street, in a conspicuous building, one of the largest in the village, now an accommodation that bears the memory of its illustrious tenant in its name, a palace that had once been a convent, and from its windows you can see the valley. When one encounters the small squares with an open view of the plain and the sea, one understands what the strategic importance of this village was in earlier times, when it was a garrison that controlled traffic in the Magra valley and access to the port of Lerici, a small port of call for ships bound for Genoa. And then Trebiano too knew different rulers: it was first of the Bishops of Luni, then came under the control of Pisa, and finally, in 1254, it was bought by the Genoese. And it is precisely the castle on top of the village, distinguishable even from miles away, that is perhaps the most conspicuous witness of those times. Falling down, devastated, crumbling, yet still capable of instilling a certain uneasiness, a noble ruin that from the heights of its towers, its arches now bitten by creepers, its walls once strong and now perilous, seems to retain albeit with difficulty the strength to dominate the village, an imposing ruin that has survived looting, neglect and history. An elderly woman from the village tells me about when, decades ago, one could still climb up to the castle, tells me about when there was life in the village, when institutions cared more for their historical memory. The access road, beyond the brushwood surrounding the fortress, is barred, a gate prevents entry. It is private property. One is just in time to cross the small expanse of vegetable gardens that anticipates the castle to stop and look at the perimeter walls. Or what's left of them. Legend has it that in one of the recesses of the fortress, inside one of those stone walls, was hidden the original manuscript of Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy. And again the legend goes that none of all those who set out to look for it have ever found it. There is, however, as with every legend, a kernel of truth: the poet really did stay in these lands, during his exile from Florence. It was 1306, and he had been called to serve as procurator for Marquis Franceschino Malaspina during the negotiations of the Peace of Castelnuovo, which ended a seven-year war between the Malaspina and the Bishops of Luni. In Castelnuovo Magra, on the ruins of the Castle of the Bishops of Luni, a plaque commemorates the poet's diplomatic assignment.

We do not know if Dante Alighieri was ever in Trebiano. There was, however, another man of letters, Jean-Paul Sartre: when he came here with Simone de Beauvoir to visit Hélène, his de facto sister-in-law, he would go and relax on the bench in front of the church. Someone in the borough, someone who was already here in the 1960s, swears he still remembers Sartre's silhouette in the shade of the plane trees that hide the facade of St. Michael's. Walking through the village, one would not know: there is no longer any trace of the sort of Parisian exclave that enlivened Trebiano's summers, there is no longer the "summer hustle and bustle of the French in Saint-Germain-des-Près," as Marco Ferrari called it. There is no longer, on the banks of the Magra, that gathering of writers, poets, men of letters, and intellectuals that enlivened the summers of yesteryear and honored the name of the gulf on which the villages of the Riviera overlook. There is no more sign, no more memory, no more atmosphere even remotely comparable. All gone. All confined to the pages of books and the memory of those who were there. Only ghosts remain under the shadow of the plane trees.