The erotic ceramics of the National Archaeological Museum in Tarquinia.

The National Archaeological Museum in Tarquinia preserves an important nucleus of Attic ceramics with erotic subjects: here are the subjects and their meanings.

By Federico Giannini, Ilaria Baratta | 15/07/2022 11:19

The room of ancient ceramics of the National Archaeological Museum of Tarquinia is one of the passages of the visit itinerary of Palazzo Vitelleschi where the public lingers the longest, given the vastness and importance of the collection of figured vases preserved here. This is material from excavations in the area, which flowed into the collections that in 1924 gave rise to the present museum, the result of the union of several collections (the municipal one, that of the Bruschi-Falgari family, and other private nuclei). In this collection a role of considerable importance is played by the nucleus of Attic ceramics with erotic subjects, which is characterized by a quantity and variety of subjects that has few other equals: the very dense presence of Etruscan tombs and sepulchres around the city of Tarquinia has, moreover, allowed the discovery of a great abundance of ceramics, since it was typical Etruscan custom (Tarquinia was one of the cities of the Etruscan Dodecapolis, that is, the set of twelve important city-states allied with each other) to insert these objects in burials, a circumstance that has allowed us to receive a very high number of intact Attic ceramics. The productions ofAttica had in fact found a very flourishing market in Etruria, since the Etruscans, in continuous contact with the Greeks, had cultivated a strong predilection for Greek-produced pottery, which was used for everyday uses, but also for funerary rituals (the Etruscans used to lay food, drink and crockery in tombs, objects that this ancient civilization considered useful for the deceased's journey into the afterlife). This taste was especially widespread in Tarquinia, one of the most Hellenized Etruscan cities.

The vases with erotic scenes from Tarquinia can be placed in a period between the early and mid-fifth century B.C. (a period that coincides with the heyday of pottery with an erotic background, which will tend to disappear around the beginning of the fourth century B.C., due to the fact that this art will begin to favor other subjects, and the erotic ones will move to other media), and it is interesting to note that the ceramics of the National Museum of Tarquinia are distinguished by the fact that the scenes depicted are almost all explicit. According to archaeologist Otto Brendel, who has devoted a lengthy study to erotic art in the Greco-Roman world, the Greeks' interest in sex could be explained on religious grounds: their religion, in fact, had more to do with the human dimension than with the cosmic dimension and thus tended to be socially and morally oriented, and the deities themselves were "prototypes not so much of natural forces as more of human attitudes and actions" (thus Brendel).

A further distinction then needs to be made, since in Greek art one can speak of sexualsymbolism on the one hand and erotic representations on the other: the latter could have both Olympian gods and ordinary mortals as protagonists. And the proliferation of sex scenes even among ordinary people could be explained by thevery open attitude the ancient Greeks had toward sex, but also by the fact that archaic Greek art at the dawn of the 6th century BCE (that is, when erotic scenes began to spread) was particularly conducive to accommodating realistic subjects and scenes taken from everyday life. The erotic scenes in Attic ceramics of the time, Brendel points out, can therefore be considered "genre scenes": "lovemaking is part of people's social life," the scholar explains, "and therefore the artists of the time recorded the various ways of doing it through an enthusiastic and acute attitude, with a taste that often proves empathetic but without traces of sentimentality [...]. Erotic depictions, like any other genre image, describe people, their actions and the situations in which they act, all reported faithfully."

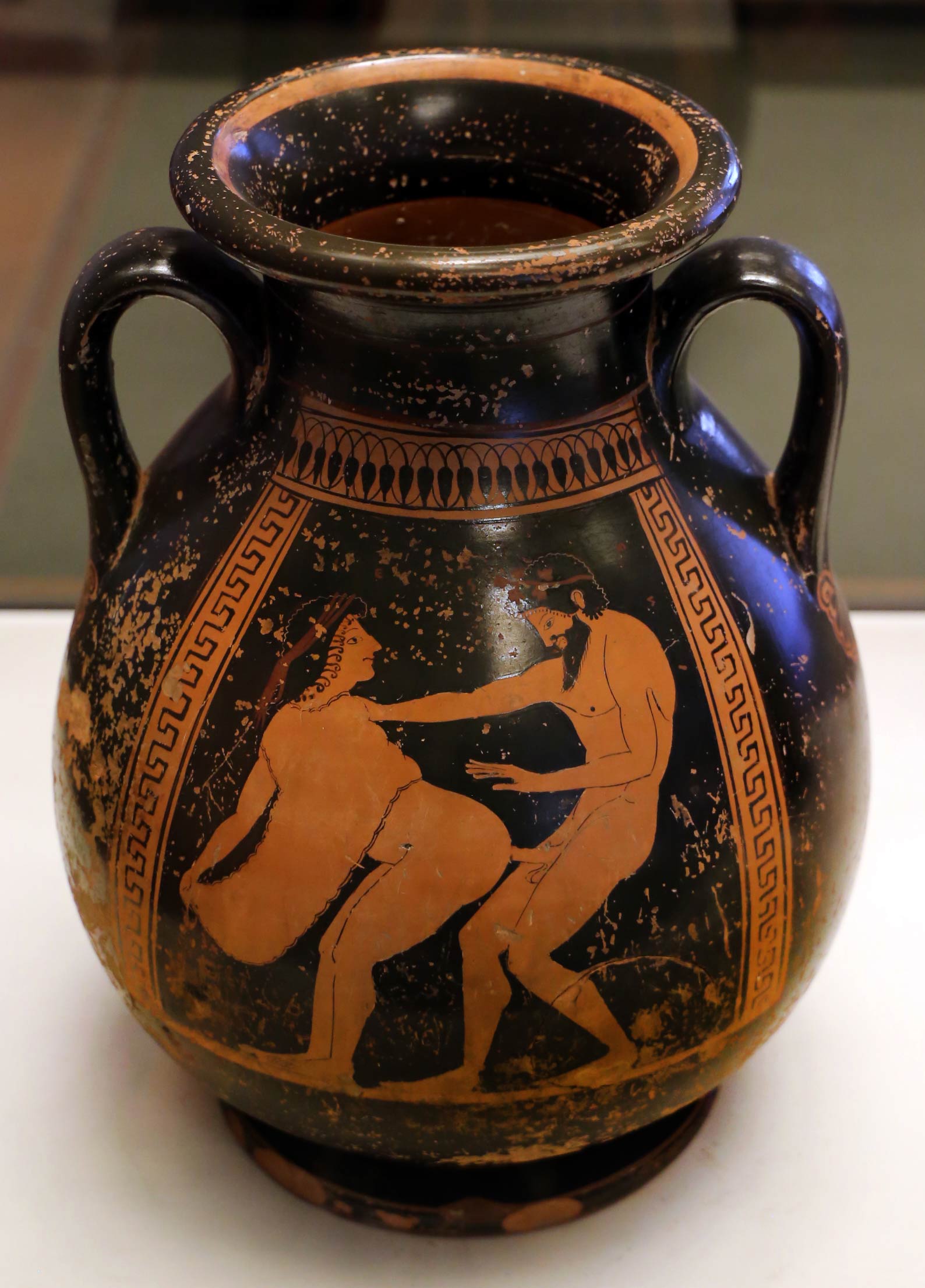

Tarquinia ceramics show homoerotic scenes (between men and between women), as well as scenes of heterosexual love. A rather usual image is one attributed to the Painter of the Cage and depicted on a kylix, or wine cup: we see two lovers, one bearded and the other younger and bearded, exchanging effusions, with the older one drawing his hands closer to his friend's sexual organ, and the younger one holding a hare in his hands. This is a typical scene of pederasty, a social custom in Greece at the time: it can be seen as a kind of sexual initiation of a young person, and therefore considered important for sentimental but also social and cultural formation. The roles were well codified: on the one hand theerómenos, that is, a beloved and passive young man in adolescence, and on the other an erastés, a lover and active man, who during courtship was used to offer gifts in kind to theerómenos, in this case the hare, a constant presence in scenes of this type ("more than assuming an attributive function for the lefebo," explained scholar Mario Cesarano, "it constitutes in terms of iconographic language a true synonym of it: prey par excellence in common imagery, it becomes a transfiguration of thefebo, the object of the amorous hunt."). Scenes of courtship are also seen in the crater (a large, tall, rounded vase in which watera and wine were mixed) attributed to the Orchard Painter, where we observe several pairs of men and adolescent girls intent on their amorous vicissitudes.

Decidedly unusual, on the other hand, is the scene that Apollodoros, one of the leading potters active around 500 B.C. (we know his name as it has been found in several vases that can be attributed to him), executes on a kylix: we find two completely nude women, one standing holding a cup, and the other crouching as she rubs her hand on the other's pubis. What might appear to be a scene of lesbian love has been variously read either as a depiction of a depilation (the one at the bottom is thus shaving the pubis of the other), or as a description of the preparations that two etére are making in preparation for a banquet following which they will join their men. The etére were courtesans: not simply prostitutes to satisfy the instincts of the males, but escorts who had to be brilliant, be able to hold conversations even at a sustained level (their culture therefore was generally superior to that of other women of the time), and possibly even indulge themselves (a figure similar, in essence, to that of the courtesan in sixteenth-century Venice). In this scene the kneeling woman is probably anointing her companion's vagina with perfumed oils to prepare her for intercourse. It could, however, also be a prelude to lesbian intercourse: although not much is known about female homosexuality in ancient Greece, there remain the poems of Sappho that tell us about the love of a woman for another woman, and then again the verses of Anacreon, the accounts of Plutarch. Lesbian love must therefore have been practiced in ancient Greece, although without probably taking on the connotations of a codified social practice like love between men.

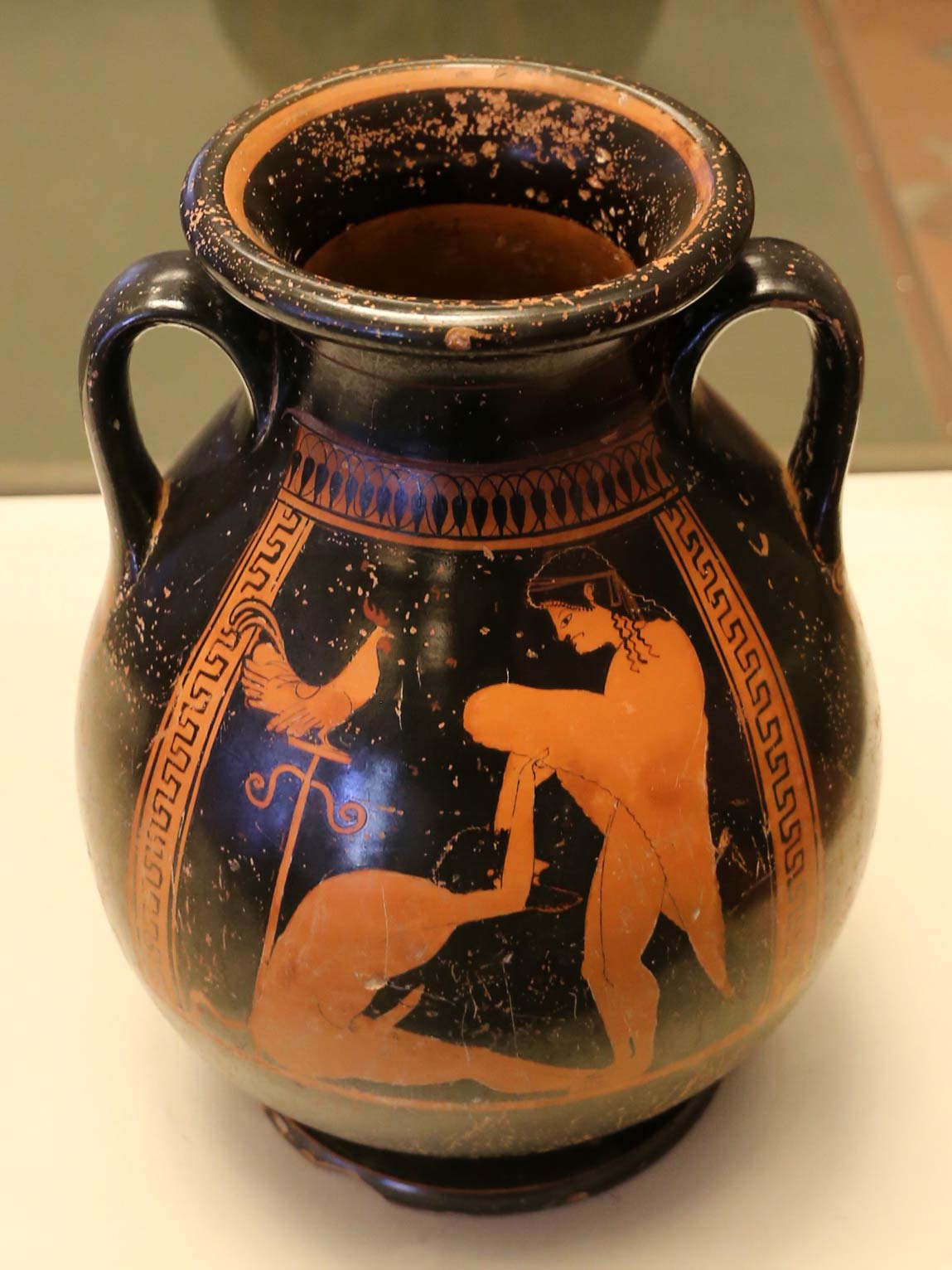

In the collection of the National Museum of Tarquinia, however, scenes of heterosexual love are in greater numbers: these are mostly explicit sexual intercourse, either caught in full swing or during preparations as happens, for example, in the pelÃke (a liquid vase) attributed to the Nikoxenos painter's field, where we see in one scene an ityphallic man (i.e., with an erect penis) lifting a woman's tunic, after which he joins her in coitus in which he takes her from behind, just as happens in the Briseis painter's kylix, where the woman, who in this case is complitely naked, rests her elbows on a support while a man penetrates her equally from behind. In the two kylixes by the Triptolemos painter, on the other hand, we see two couples engaged in the Viennese oyster position, a variation of the classic missionary position in which the woman rests her ankles on the man's shoulders (in this depiction, too, we clearly distinguish the man's penis beginning to penetrate the woman). In the work of the painter of Briseis and in one of the two kylixes of the painter of Triptolemos we see that the woman has tied to her thigh a thin amulet, which identifies her as an etéra, an object that we do not see in the other depictions.

Critics have essentially always identified the women depicted in these scenes as etére, but recently this belief has been challenged by scholar Alessandro Baccarin, who has found this interpretation misguided by our understanding of romantic relationships. "The categories that art historians and antiquarians used to 'read' these scenes," Baccarin explains, "were those of phallocentrism and pornography: these images indicated the violence suffered by women in the Greek world, their use as sexual objects, their multiplication as sexual solicitation for the male gaze. Hence the identification of female subjects portrayed with prostitutes, ether or sexual entertainers, identification possible through the association between nudity-sexual explicitation and prostitution-pornography. This type of reading, common to the studies of the 1970s and 1980s, was based on the distortional application to the ancient of a modern gaze, a gaze activated by equally modern categories. The assumption, for example, that that type of pottery was precluded from the gaze of women and that it remained confined to the banquet hall to be handled exclusively by men, was based on the application to the ancient world of precisely that segregative dimension that nudity and eroticism had undergone in museum policy or in the management of pornography between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries." The identification of women in Attic ceramics with erotic subject matter thus remains an open problem, to be solved bearing in mind that the ceramics were objects of everyday use and ended up being part of grave goods. The conclusion, according to Baccarin, is that "we are faced with a declination of eroticism that is foreign to us. Lamplesso is in the first place an ornamental motif. Secondly, it recalls the unity between pleasure, love, desire, fertility. A set of categories these that we are accustomed to disassociating between knowledge (sexology and pornography), between spaces (the pornographic and the non-pornographic, thus the private and the public), between different subjects (the prostitute and the common woman). After all, in the Greek world it was the women who managed the funerary rites for their relatives, and thus it was their hands, as well as their gaze, that placed and chose the erotic-themed symposium pottery in the tombs of their family members."

Finally, a curiosity: the ceramics of the National Archaeological Museum in Tarquinia had been greatly appreciated by the great English writer David Herbert Lawrence, who in 1927, during his last trip to Italy, visited places in ancient Etruria, and his notes flowed into the book Etruscan Places, published posthumously in 1932. The chapters are divided by cities visited, and the second is devoted to Tarquinia: the section on the Latium city concludes precisely with a visit to the museum in Palazzo Vitelleschi, which only three years after its opening had a layout quite similar to the present one, with the stone sculptures and sarcophagi displayed on the first floor, and the ceramics in the rooms on the main floor.

"On the upper floor of the museum," Lawrence writes, "are many vessels, from the ancient ceramics of the Villanovans to the more recent black pottery decorated with carvings, or undecorated, called bucchero, down to the vessels, plates and amphorae that came from Corinth and Athens, or the painted vessels made by the Etruscans themselves, which roughly followed Greek motifs." According to Lawrence, the art of painted pottery was not really the specialty of the Etruscans, but from the collections of Tarquinia one can sense all the passion that this ancient population cultivated toward this art. "In very ancient times," writes the author of Lady Chatterley's Lover again, "the Etruscans must have sailed their ships to Corinth and Athens, bringing perhaps grain and honey, wax and pottery in bronze, iron and gold, and returning with these precious vessels, and objects, essences, perfumes and spices. And the vessels brought this way from the sea by reason of their beauty were to be considered treasures for the household." We, too, consider them extremely valuable today: they are objects of great beauty, and they also reveal so much information about life at these ancient civilizations.

Reference bibliography

- Mario Cesarano, Danae, Perseus and Acrisius among the Etruscans of Spina, in Engramma, 178 (2020-2021), pp. 45-88

- Alessandro Baccarin, Archaeology of Eroticism. Rise and oblivion of the Greco-Roman ars erotica, Hephaestus Editions, 2018

- Elisa Marroni, Attic red-figure vases from Tarquinia, ETS Edizioni, 2017

- Vincenzo Bellelli, Particularities d'uso of Etruscan common pottery, in Mélanges de l'École française de Rome - Antiquité, 1262 (2014)

- Sergio Musitelli, Maurizio Bossi, Remigio Allegri, History of Sexual Customs in the West from Prehistory to the Present Day, Rusconi Libri, 1999

- Otto Brendel, The Scope and Temperament of Erotic Art in the Greco-Roman World in Theodore Bowie and Cornelia Christenson, Studies in Erotic Art, Basic Books, 1970, pp. 3-69.