The Museum of Human Anatomy in Pisa, a journey through the human body among mummies and embalmed heads

The university museum has a rich and varied collection that includes not only anatomical artifacts, but also archaeological relics including mummies, vases and embalmed heads-a collection perhaps not suitable for the most impressionable spirits, but certainly fascinating.

By Jacopo Suggi | 13/02/2025 19:07

University museum collections generally derive their origins from an Enlightenment conception, which changed an encyclopedic approach to knowledge to a specialized one. Guided by this new instance, collections born as Wunderkammer, with the purpose of astonishing as well as eruditing, were dismembered to reformulate themselves into science museums, didactic appendages to university study. The same events can be read in the university museums of Pisa, where, for example, the Grand Ducal Wunderkammer, once adjoining the botanical garden rooms, was over the centuries disassembled to give rise to more museums. Despite the specialization of these realities, some continue to boast relics pertaining to more than one field, and this is the case of the "Filippo Civinini" Museum of Human Anatomy, which is capable of combining scientific, archaeological and artistic exhibits in its collections.

Its origins are linked to the study of medicine and in particular anatomy in the University of Pisa, which was among the first in Italy to have an anatomical school. This foresight is owed to Cosimo I dei Medici, who in the 16th century established the teaching of medicine, encouraging teaching and research through the use of cadavers: this practice until then could only be carried out under illegal conditions, and it would remain forbidden for a long time in the territories under the rule of the Roman Church. In the mid-sixteenth century, Pisa was provided with the first anatomical theater, where students could attend lectures conducted through the dissection of cadavers. Over the centuries the theater found various locations, moving from Via della Sapienza, to a room in the Spedale di Santa Chiara. On these premises, the Anatomical Museum was formed, responding essentially to two needs, namely the didactic need, which was essential when no cadavers were available, and the political need to fill the gap of the absence of an anatomo-physiological collection, which was already present in many universities and cities.

In 1829, Tommaso Biancini, professor of anatomy gave life, also thanks to the support of Grand Duke Leopold II, to the first Anatomical Cabinet. Unfortunately, due to health problems, he was unable to complete his reorganization work, which was carried out instead by the Pistoiese physician Filippo Civinini. The Cabinet's collection initially consisted of only about sixty anatomical pieces, but it was soon enriched, with models coming from Civinini's personal collection, which he donated to the University. In 1836 the doctor became director of the museum, and in this capacity, he traveled far and wide throughout Italy, with the aim of enlarging the collection. In just five years, the museum could count on twenty-three staff members, and more than one hundred and twenty donations of anatomical preparations from private individuals and museums, to which were added the large donations of books and manuscripts related to the anatomical pieces.

This hard work meant that by 1841 there were 1327 preserved preparations, which Civinini promptly described and catalogued. In the early museum human elements were also juxtaposed with animal specimens, evidence of which can still be found today, which in an age that had not yet seen Darwin's theory of evolution, raised considerable discussion. In 1839 the First Meeting of Italian Scientists, a congress that brought together scholars from all over the world, was held in Pisa, and on that occasion the Anatomical Cabinet of Pisa, whose reorganization could be said to have been completed, was offered to the public.

Thanks to the signature book, it is possible to infer that visitors then were not only scholars pertaining to medical subjects, but also engineers, men of letters, merchants, artisans, etc. Civinini's successors also enriched the museum, and this influx continued apace, despite the fact that in 1884 with the founding of the Institute of Pathological Anatomy a museum of Pathological Anatomy was set up, the preparations of which flowed from the Museum of Human Anatomy.

Today the museum is located in the Institute of Human Anatomy of the Medical School, just a few hundred meters from the Leaning Tower, and directly across from the Botanical Garden of the University of Pisa. Arranged in elegant cherry wood display cases is the large and varied collection, which consists of relics of great interest.

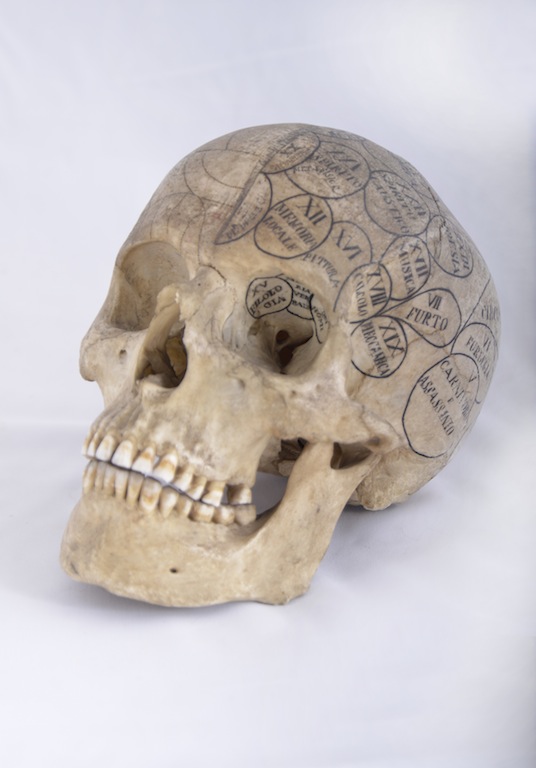

For example, a rich collection of human skulls, of which it is worth mentioning a skull with its component bones disarticulated (exploded model) and a phrenological map, i.e., a skull displaying the conceptions of the pseudoscientific doctrine of phrenology, according to which an individual's psychic and mental aptitudes depend on the morphology of the skull; thus, depending on the bony protrusions one may be endowed with a "murderous spirit," or predisposed for "theft," "calculation," and so on. Still vast is the osteological collection, which boasts whole skeletons, some artificially composed with metal wires holding the bones together, others natural, with the preservation of ligaments. Then again skeletons of exceptional stature, or belonging to different human populations. Of a fair size is the embryological collection, which through dry preparations, showcases skeletons of fetuses and newborns, from sixty days old to 2 years old.

Anatomical preparations, sometimes obtained dry others preserved in alcohol, unfold throughout the space. These make it possible to isolate and explain different phenomena and apparatuses-for example, in the angiology section there are preparations devoted to the heart and blood vessels, made by embalming and injecting colored plaster into the cavities. Also in the museum are anatomical statues, obtained from whole cadavers, showing the human organism in its entirety, or in sections. Curious are two dermatological preparations, represented some sections of tattooed epidermis, with tattoos dating as far back as 1820, showing how this practice that is very much in vogue today has decidedly ancient origins.

There are models obtained from the most varied materials: in colored wax is the interesting full-size body of a young man, which also shows a certain aesthetic sophistication in its melancholy pose of abandonment. Rather famous is the mummy of Gaetano Arrighi, a criminal who, in the first half of the 19th century, was imprisoned in the Livorno penal bath. When he died, his body, unsolicited by any family members, was the basis for experimenting with an embalming technique invented by Palermo physician Giuseppe Tranchina. This method involved injections of arsenic and mercury to counteract decay, and as can be seen from the state of preservation, it had to prove quite functional.

Arrighi's mummy was kept for very long years in the Civic Hospital in Livorno, forgotten in some basement, when not many years ago it was finally found and left to the Museum of Human Anatomy in Pisa.

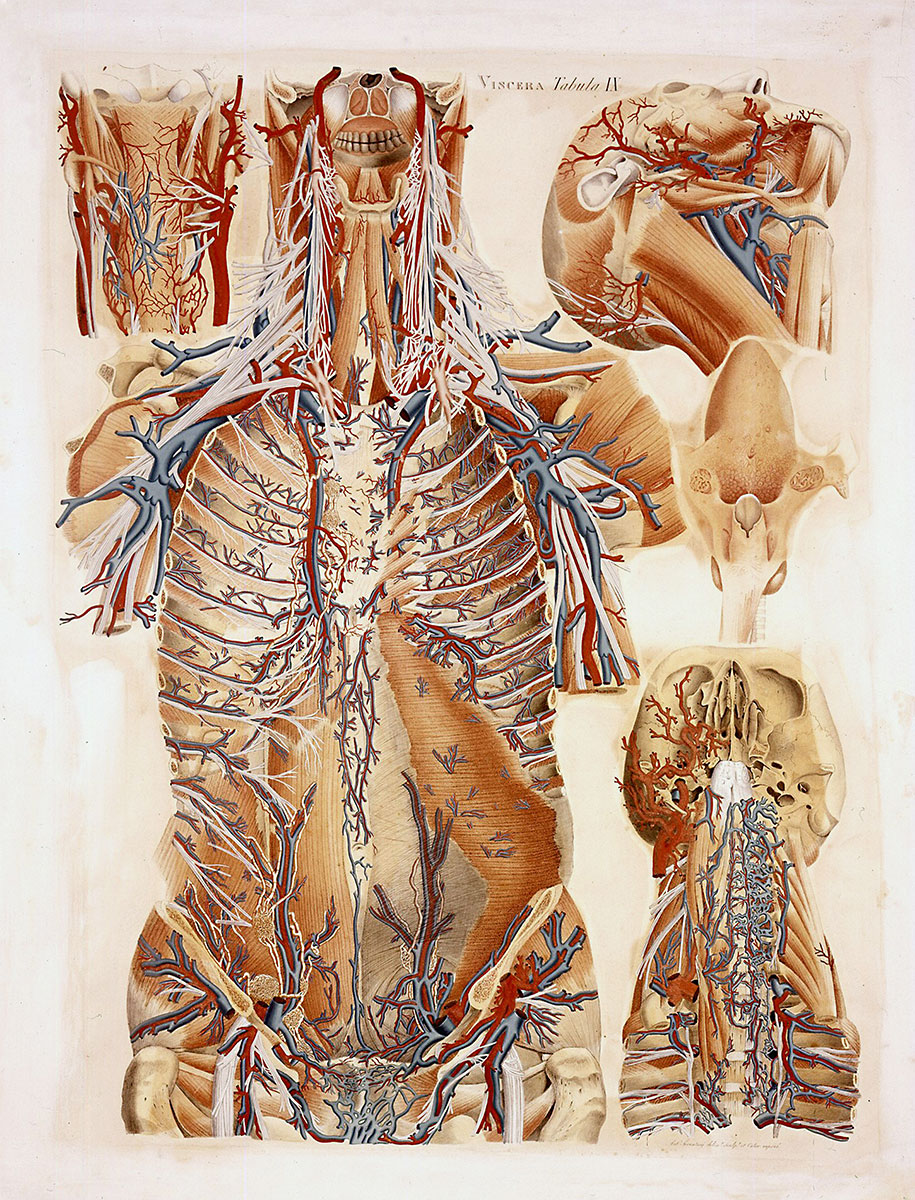

Of great fascination are the Mascagni Tables made by Paolo Mascagni, a professor in the University of Pisa in the 19th century, which are preserved along the gallery on the second floor of the Human Anatomy Section. Mascagni devised lavish watercolor anatomical plates, which depict the human body life-size in its various components and originally adorned the walls of the anatomical theater.

A certainly heterogeneous nucleus for the anatomical collection, but of definite interest, is also the rich archaeological collection, consisting of numerous relics. These include more than a hundred vessels belonging to pre-Columbian peoples such as the Chimú, who originally lived along the coast of Peru. They are artifacts made between the 12th and 16th centuries, which were used as grave goods, and in which plant remains were also found inside, now arranged in glass ampoules in the museum.

Vases sometimes of anthropomorphic forms, or decorated with effigies of animals, to which the whistling vases also belong, a name derived from the noise emitted by the air when the container was emptied, came to the museum as early as the second half of the 19th century, thanks to excavations carried out by Carlo Regnoli, and the collection was also enriched through donations from Baroness Elisa de Boileau. Belonging to the same collection are skulls, utensils and cloths and some fardos, wrappings composed of cloths that wrapped the deceased. Also added to these are two whole mummies, obtained through a spontaneous process favored by the arid climate of the Peruvian coast, caught in the fetal position that it is possible to relate to some spiritual and religious practice. One of the two mummies moreover also shows an artificially deformed skull.

Even more disturbing is a selection of embalmed heads, also of Peruvian origin. There are eight heads, including those of two babies only a few months old, belonging to individuals who were decapitated. Recent studies have speculated that the remains could be traced to men of European origin, perhaps victims of a massacre, but information on this is still limited.

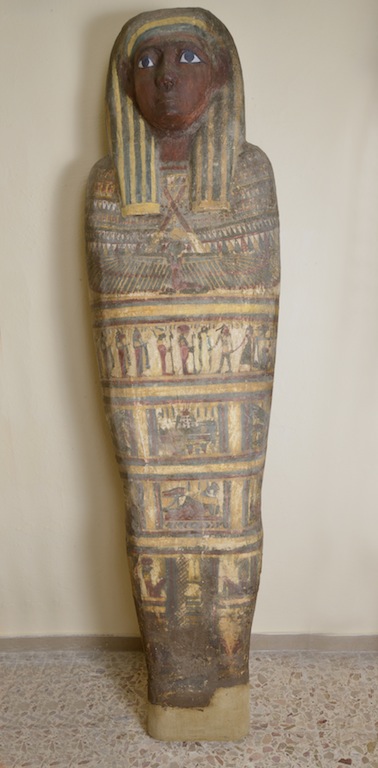

Most likely traceable to the French-Tuscan expedition conducted in Egypt between 1828-29 by the famous Egyptologists Ippolito Rosellini and Jean-François Champollion are two Egyptian mummies, one of which is still preserved in its sarcophagus. The tomb still has its splendid polychrome paintings, one depicting a procession of deities, and the other the "weighing of souls." One of the mummies, recently investigated, showed the absence of organs due to the ritual evisceration that was applied to the corpse to preserve it, and a dilated nostril, as the deceased's encephalon is extracted from that cavity.

Certainly, the collection of the Museum of Human Anatomy of the University of Pisa is not a visit advisable for the most impressionable spirits, but nevertheless, thanks to its varied and multidisciplinary collection, it knows how to offer an experience of great interest not only for scholars of medicine and anatomy, but also for enthusiasts of anthropology and archaeology, and for all those who want to have more knowledge about the nature of man. Moreover, an implication perhaps not sought after by the museum's ordinators is that it becomes a kind of memento mori, a plastic demonstration of how human existence has always been marked by a certain ephemerality.