For a rediscovery of the Renaissance in Sicily. Francesco Laurana between Palazzolo Acreide and the Val di Noto.

Sicily is home to some of the most beautiful marbles of the 15th century: those of Francesco Laurana. Works that weave a profound dialogue with the paintings of Antonello da Messina.

By Giacomo Montanari | 19/01/2022 13:42

Almost at the apex of the dense settlement of pale stone houses, which climbs to the top of the hill (where the theater of ancient Akrai still stands), on the left hand side, going up Corso Vittorio Emanuele, one encounters a flight of stairs that leads in one leap to the small square in front of the baroque mass of the church of the Immacolata of Palazzolo Acreide. The curved lines of the Borrominian façade and the Guarini echoes of the large windows, typical of the baroque language of the Val di Noto, well guard the Renaissance secret of the church, which only those lucky enough (alas, rare) to find the door open can unveil, searching with their gaze in a deep niche of its single nave. Here was moved, in an attempt to fill the deep solitudes excavated in the contexts of the works of art by the terrible earthquake of 1693, one of the most strongly characterizing Marian images for 15th-century Italy. The tangible sign of the great cultural routes of the European Renaissance, which, making a mockery of the presumed hierarchical criteria of historians and art historians, touched this (now marginal) town in the province of Syracuse, engraving on it with immeasurable softness and absolute virtuosity the signature of one of the greatest marble artists of the 15th century: Francesco Laurana.

Born in Vrana, in present-day Croatia, in an unspecified year in the first half of the 15th century, Francesco Laurana represents one of the most significant personalities in the sculptural landscape of Renaissance Italy, and particularly in the area of Naples and Sicily. Documented in Naples in 1458, already with the rank of magister, Laurana spent a certain period of activity in Provence (a region, by the way, where he would probably end his life between 1510 and 1512), only to find himself back in Sicily in 1468, after passing through Naples again. His activity in the area of Sciacca and Partanna, though supported by numerous documentary evidences, is, however, still partly obscure, and many of the works at first attributed to the Dalmatian artist's chisel have been more correctly traced to a workshop setting. It may, however, have been the reason for Laurana's call to the area that he (already a sculptor in the service of the King of Naples) was commissioned to paint the funeral portrait of Eleanor of Aragon, who died in 1405 and is buried in the monastery of Santa Maria del Bosco in Calamatauro. Might not Eleanor herself be the woman eternalized in the marble bust now preserved in the Regional Gallery of Sicily at Palazzo Abatellis in Palermo and often also identified with Isabella or Beatrice of Aragon?

It remains a fact that the typology of the marble bust-portrait, often a post-mortem simulacrum, was to be a constant production in Laurana's career, the apex of which is perhaps represented by the famous and qualitatively extraordinary bust of Battista Sforza, now in the Bargello Museum in Florence and datable to the years immediately following this first Sicilian sojourn, around 1474. The most important work of his insular sojourn, however, is the design and sculptural realization of the Mastrantonio Chapel in the church of San Francesco in Palermo, conducted together with the sculptor Pietro de Bonitate. These were years, these, in which Laurana's style and sculptural language were imbued with the executive methods of Domenico Gagini, with whom Laurana had already collaborated in Naples. Most active in Sicilian soil though of Lombard origins and with strong and lasting roots in Ligurian soil, in Genoa, Gagini built his sculptural experience also from his Florentine experience in the workshop of Filippo Brunelleschi, an alumnuship whose many eloquent reflections would manifest themselves in the happy outcomes of his stay in the Superba.

Laurana's sculptural vocabulary, so rich in chisel refinements still late Gothic, but fully aware of the new representative instances of the Renaissance in the treatments of volumes, surfaces and in the calm and sweet pathetic expressiveness of the faces of his works, is certainly enriched in the dialogue with the achievements of the most important painters active in the panorama of the Italic peninsula and, in particular, in Sicily. While on the one hand, in fact, the technical constancy in the working of marble with the operative methods of Gagini and Bonitate is evident, on the other hand, it is impossible not to grasp the remarkable familiarity between the sculptural language and the presence in space of the works of theDalmatian artist and the contemporary or slightly earlier works of Antonello da Messina (Messina 1429/1430-1479), who had left and was still leaving (in those last, extreme, years of his painting career) significant traces on the island territory that had given him birth.

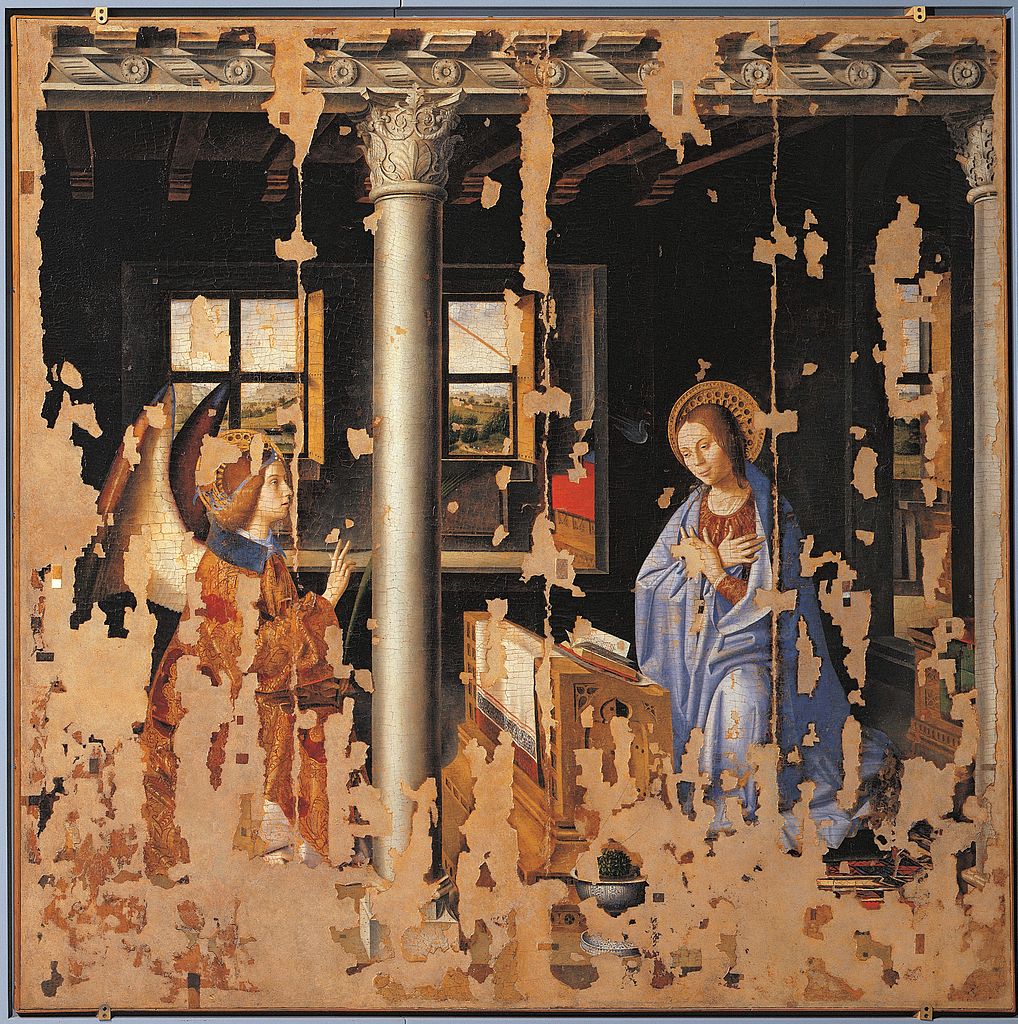

At a short chronological and geographical distance from the only work signed and dated by Laurana in Sicily (another similar case are the medals made in Provence), the Madonna of the Snow made for the city of Noto in 1471 and today preserved in the church of the Santissimo Crocifisso again because of the "aftermath" of the earthquake at the end of the seventeenth century, the paths of Antonello and Laurana cross, extraordinarily, in Palazzolo Acreide. Certain and documented to 1474 is the painter's realization of the magnificent Annunciation now in the Palazzo Bellomo in Syracuse, found butchered by moisture and repainting in the church of the Annunciata in Palazzolo in 1897; while certainly'else dating from the period between 1472 and 1474 (but lacking a certain date) is the Madonna della Grazia sculpted by Laurana for the lords of Palazzolo, the Alagona family, for the church of Santa Maria della Grazia (now destroyed), preserved in the above-mentioned niche in the church of the Immacolata.

If the direct relationship between Antonello da Messina and Francesco Laurana cannot be documented through archival reconnaissance, it is, however, undoubted and highlighted already by the acute observations of Bernard Berenson, Adolfo Venturi and Hanno Walter Kruft, how the language of synthesis of spatiality, the modulated smoothness of the tonal passages in the definition of faces, at the level and chromatic and compositional, as well as the narrative and expressive effectiveness of the figures, clearly show that a relationship there was and (in all probability) was one of mutual exchange. I prefer to think of a younger Laurana, able to perceive the grandeur and internationality of Antonello's language (returning from Venice and from the fruitful dialogue with the central Italian realities of higher humanism high, such as the Urbino circle and Piero della Francesca), who already perfects, in the Palazzolo Madonna, which precedes (probably) Antonello's altarpiece, a thoughtful and rethought mode of expression in its various outcomes (the examples of Noto, Erice and Palermo, enclosable in the three-year period 1468-1471, are worth here). The Virgin's fine veiled smile, the refinement of the mantle that descends to open at the neck, stopped by a brooch, the volumetric and rhythmic drapery, and the weighted softness of the gestures that stage a delicate, perfectly balanced contraposto, show a rich and perfected vocabulary, certainly indebted to the Antonellian gravitas of works such as the extraordinary Madonna Salting (c. 1460) in the National Gallery in London, where the silent dialogue of Jesus and Mary, their eyes half-closed in contemplation of their son, is emphasized by the eloquent gestures of the alabaster hands that flaunt Christ. On the other hand, there is no doubt that Antonello, too, in his Palazzolo performance, probably also looked at and kept in mind Laurana's recently completed work, just near the Church of the Annunciata, for which the Messina painter was working. Similar intentions, in fact, can be seen in the rhythmic draperies enlivened by ring folds of the Virgin's cloak in the Palazzo Bellomo panel, just as the gestures of the hands and face, bent with familiar softness in the dialogue with the Child (for Laurana) and dissolved in a nod and a smile of assent to the Announcing Angel in Antonello's painting, appear to be of similar layout. Sensibilities shared and circulated in most artistic contexts (pictorial and sculptural) of the time, yet here so tangibly close as to demonstrate a relationship not only of place but also of artistic communion.

Beyond the debts and credits spent reciprocally between these two exceptional interpreters of the Renaissance temperament in Sicilian lands, however, it will be worth emphasizing the incredible conjuncture that brought two artists (and therefore two works) of such stature to Palazzolo Acreide in neighboring years. Incredible, perhaps, is the wrong term, because it is the result of the amazement generated by thinking of a place like Palazzolo Acreide (albeit an important UNESCO-protected heritage site as one of the places of the late Sicilian Baroque) as a real "center" of cultural aggregation, patronage and therefore avant-garde artistic expression in the mid-15th century. The accounts, in fact, must be made considering not so much recent history as the weight of the Palazzolo community in the 15th century: a weight that was of quite a different magnitude and that therefore saw the awareness of the centrality of this place celebrated through the figurative language of two of the greatest artists of the international Renaissance, in painting and sculpture.

To highlight, should there ever be a need, the importance today of dwelling on the study of what appear to be the "marginalia," the stories of the places and works that seem to frame the great strands of history and the history of 'art, I take this opportunity to highlight how in the very high quality of Palazzolo's beautiful Madonna della Grazia, the most synthetic, disruptive and innovative language is contained (perhaps) in the very bas-relief that adorns its base. A masterpiece within a masterpiece, which, like the Madonna of Laurana half-hidden and invisible in its church too often closed to the public, waits to be rediscovered and cherished as a sign of the greatness of a land that saw the works of the best human ingenuity.

In 2016, with great intelligence, the Region of Sicily, the Municipality of Palazzolo and the Superintendence of Cultural and Environmental Heritage of Syracuse (in the person of Rosalba Panvini) promoted and realized an exhibition that compared again, after more than a hundred years, Antonello'sAnnunciation with the Madonna of the Snow from Noto and Palazzolo's Madonna of Grace executed by Francesco Laurana. An extraordinary dialogue that has unfortunately remained without any echo either in the territory or, even less, in the scientific literature and that survives, today, only in the beautiful photos of Salvo Alibrio.

And while it is true that, certainly, such an operation cannot be continuously repeated because of the precarious conservation conditions that afflict Antonello's table and the inappropriate removal of the sculptures from their current church locations, it could (on theon the other hand) be well resumed with installations aimed at the in situ narration of the Dalmatian master's works, today lacking any apparatus that would enhance their prestige, quality and importance in the panorama of Renaissance art. Today, traditional apparatuses are being joined by other digital technologies that could allow Antonello da Messina's altarpiece to be evoked in its original location, in Palazzolo, on the altar of the Church of the Annunziata. Or again: many digital channels, from social networks to more elaborate communication strategies, can be activated to tell what is, by far, a more unique than rare presence, with more than one story to tell. A modality that would have the certain effect of contributing greatly to pushing visitors (which in the Val di Noto, certainly, there is no shortage of) to visit the beautiful Madonna of Palazzolo or (why not?) even that of Noto. But, to do so, one would first have to be certain of at least one thing: the possibility, to date extremely rare, of finding these churches open.