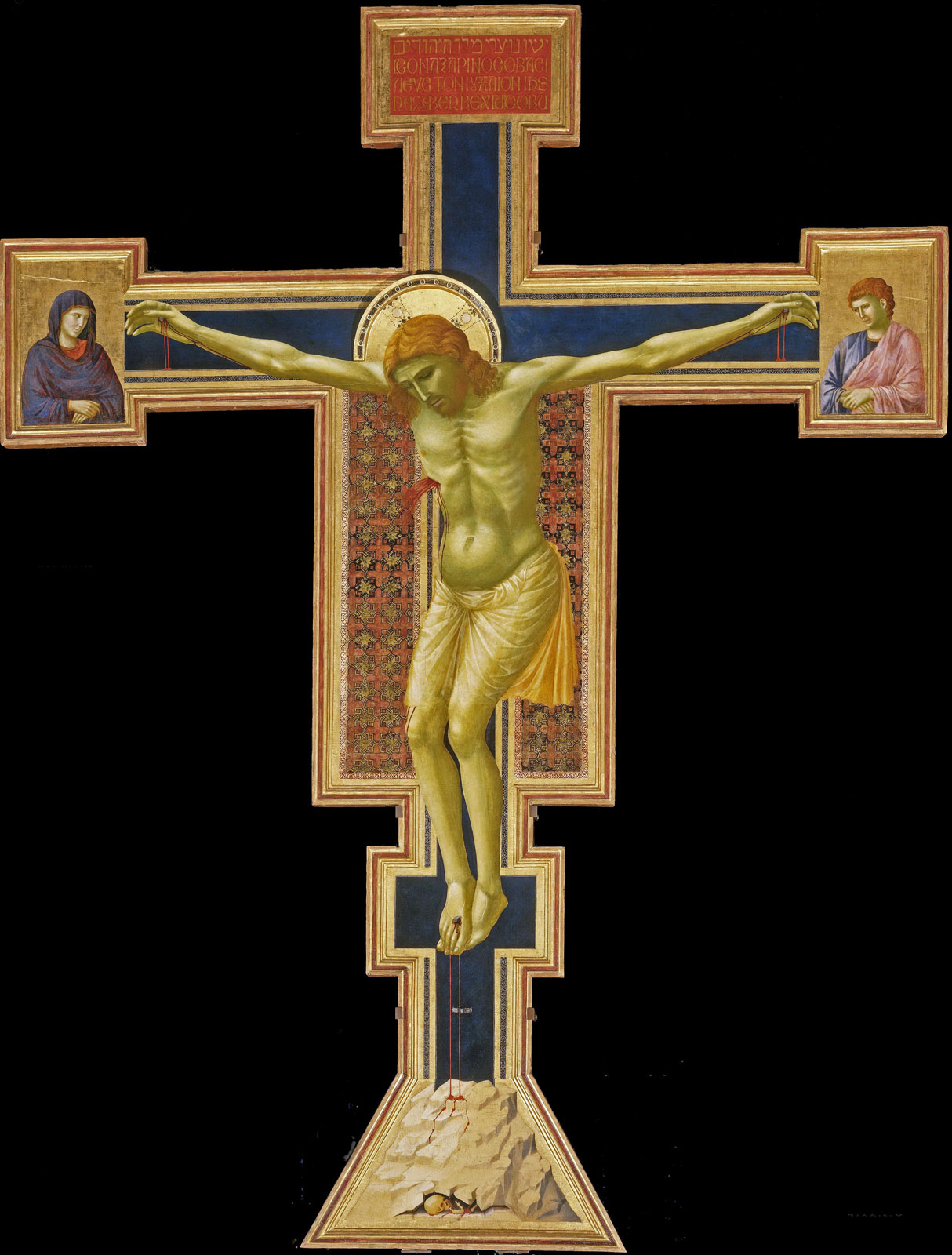

Giotto, the Santa Maria Novella Crucifix: the first real Christ on the Cross in Italian painting

With the Crucifix of Santa Maria Novella, probably executed in the first half of the 1390s, Giotto achieved a real revolution: for the first time, the faithful saw a real body on the cross.

By Francesca Interguglielmi | 18/12/2021 02:02

In the Florentine church of Santa Maria Novella is a work that, at the end of the 13th century, marked a caesura in the history of Italian art. Entering the church, raising our gaze along the nave, we can in fact admire a painted cross belonging to the initial phase of Giotto's extraordinary journey, who as early as the end of the 14th century was identified by Cennino Cennini as the one who "remutated the art of painting from Greek to Latin and reduced it to modern." Regarding this work we have a documentary record dating back to 1312: in the will of a certain Ricuccio di Puccio del Mugnaio there is a provision to direct a sum of money to be used for the supply of oil in order to fuel and keep lit a lamp in front of the large crucifix that Giotto made for the Dominican church in Florence. This is the oldest documentation regarding the cross made by the painter for the church of Santa Maria Novella. It is later mentioned in Lorenzo Ghiberti's Commentari and Giorgio Vasari's Lives. Its present location inside the church was studied on the basis of the position of the ancient partition, for which this work was probably originally intended.

This is the first occasion on which Giotto is confronted with the typology of the painted cross. The iconography is that of the Christus patiens (Suffering Christ), which appeared in Italian painting in the middle of the century with Giunta Pisano and was picked up and stylistically embellished by Cimabue. In addition to the dominant figure of Christ nailed to the cross, the side capitals feature the grieving Virgin and Saint John. The lower part of the woodwork ends with a trapezoidal suppedaneum, in which the painter depicts Golgotha with Adam's skull. Giotto in this first cross of his immediately presents himself with a new and powerful figurative language compared to the contemporary painting scene, capable of adding new values to that image of devotion. For the first time in Italian painting, the depiction of Christ on the cross gives us back the perception of a real human body, in which no aspect of the divine is traceable. Our gaze is offered a human body with a well-defined structure, in which muscles, bones and tendons can be identified. Of that suffering body, we can perceive the weight thanks to the position Giotto gives it: the figure, in fact, is no longer depicted following the unnatural arching that still persisted in Cimabue's crosses, but is drawn downward and we have the impression that it is jutting out from the surface on which it is represented.

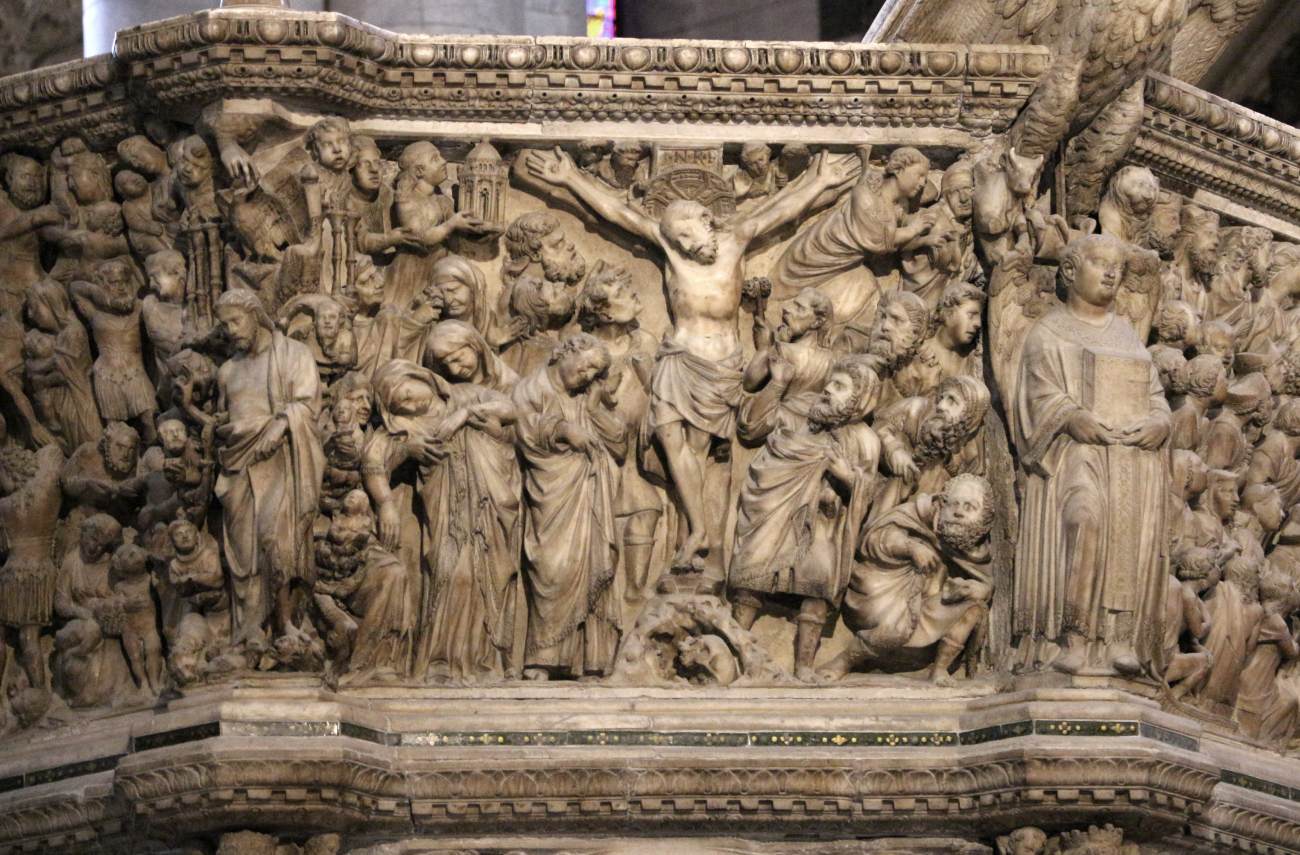

The results achieved by Giotto with this work are extraordinary and would open new vistas in Italian painting from the late 13th century onward. Some details are truly exceptional and already clearly illustrate the innovations Giotto introduced into the painting of the time. For example, let us look at the marvelous detail of the nailed hands: Giotto tries to represent as realistically as possible the position assumed by the hands nailed to the cross, which are not open and outstretched as before, but are closing in on themselves. The painter's desire to try to reproduce the naturalistic datum as faithfully as possible to reality, breaking away from the pictorial tradition, is evident. Giotto's attention and ability to achieve these naturalistic details allow him to give that body a truly human appearance, without letting anything divine shine through. The body is shaped through a skillful and confident use of chiaroscuro, achieving unprecedented plastic outcomes. Max Seidel, in his masterful essay on the Cross of Santa Maria Novella, highlighted Giotto's relationship with the sculpture of the time. The latter, in fact, had achieved strongly naturalistic outcomes in Italy by the mid-13th century, first with Nicola Pisano and later with his son Giovanni and Arnolfo di Cambio.

Even in the figures of the mourners, which are smaller in size than the central Christ, Giotto changes the pace with respect to contemporary painting culture: in fact, it is no longer the position of their arms and faces, and therefore their attitude, that expresses their pain, but rather this feeling is to be sought in their gazes, to which the painter gives great importance in the representation and will be one of the great innovative elements of his painting.

During the very important restoration, completed in 2001, carried out by theOpificio delle Pietre Dure, diagnostic investigations gave the possibility to discover that Giotto had had the dimensions of the woodwork altered in order to be able to realize his new idea of Christ on the Cross: in fact, the painter needed more space to be able to realize the human physicality of Christ. Moreover, it was observed that he had made an extraordinary preparatory drawing freehand, albeit with the help of a patron. Some of the details of the preparatory drawing observed in infrared, such as the depiction of the beard, are fully revealing of Giotto's new approach to painting: in fact, they are drawn not following models from the iconographic tradition, but drawing inspiration from direct observation of reality. In the final pictorial rendering, however, Giotto then had to mitigate this new naturalistic rendering of his, probably compromising with the expectation of the patrons: the beard, in fact, appears to the observer groomed, with the hairs neat and combed, not curly and unkempt as can be seen in the infrared analysis.

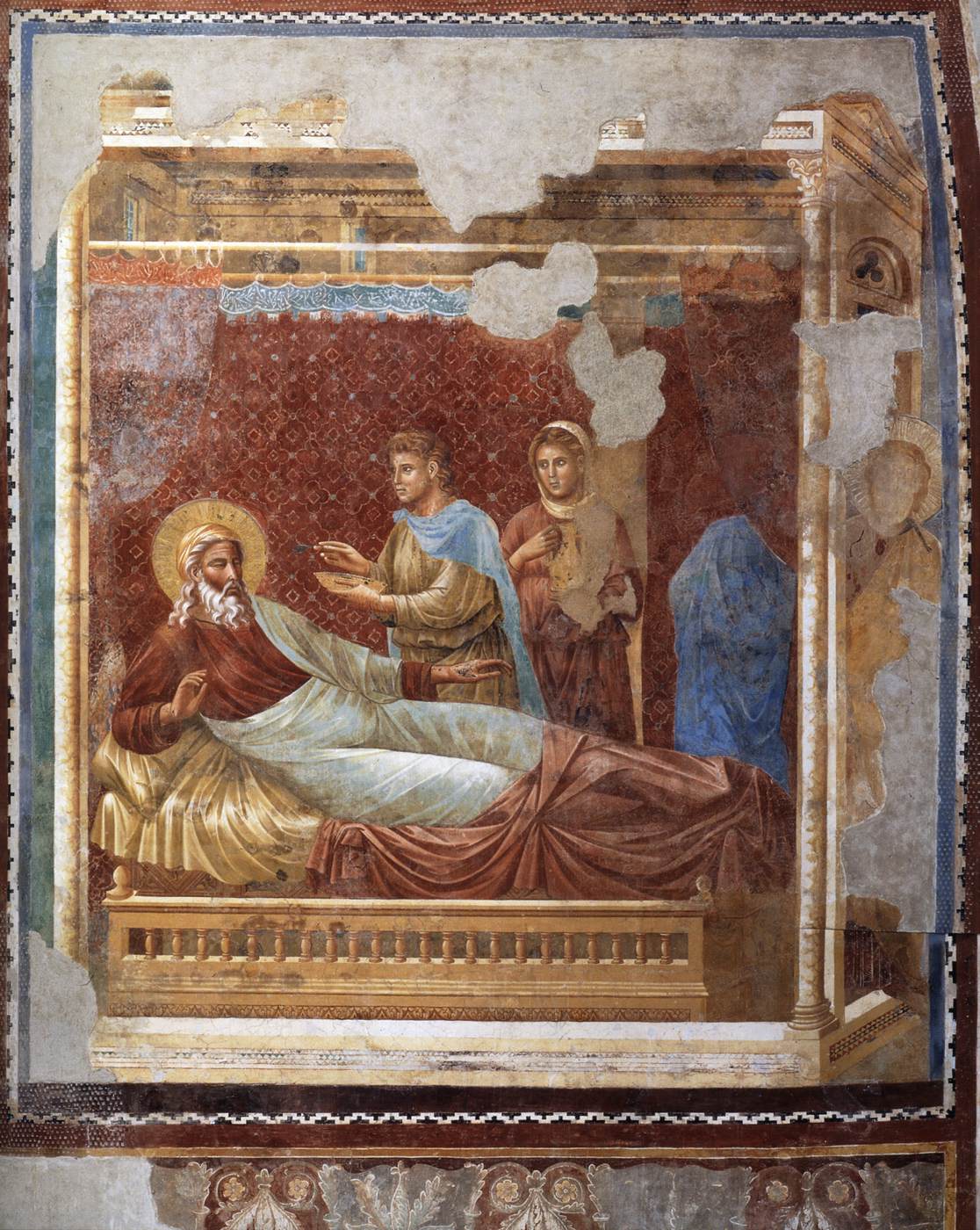

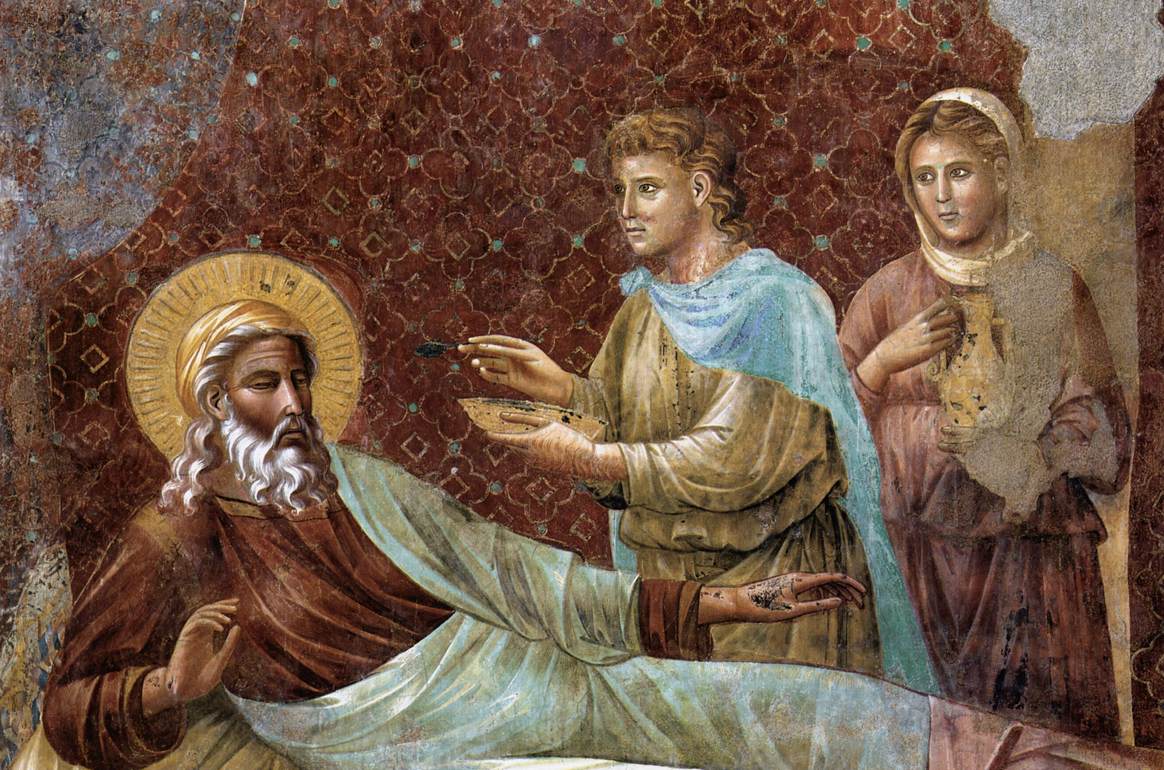

The authorship of this work was hotly debated during the twentieth century. Robert Oertel in his 1943 essay Svolta nella ricerca su Giotto (Turn in Giotto Research ), in which his ideas on Giotto's early work published as early as 1937 were published in a more analytical manner, thought that the debate regarding the attribution of the painted cross in Santa Maria Novella would soon be over because the work's authorship to Giotto was convincing. In the following decades, however, the debate resumed determined vigor. Detractors of this attribution disputed, in particular, the realism of the Florentine Christ compared to the idealism of the figures in the Scrovegni Chapel, a work attributed to Giotto with certainty. Moreover, this work is able to create a fruitful environment for comparison with respect to another artistic context, that of the nave of the Upper Basilica of St. Francis in Assisi with the Stories of Isaac and subsequent depictions, which has inflamed the debate in 20th-century art historiography concerned with medieval Italian painting and which has come to be known as the "Giotto question." Looking at the figures on the Florentine Cross and those in the two narrative scenes of the Stories of Isaac, one can identify significant stylistic similarities that indicate that the two compositions were conceived and executed by the same artist. Observe, for example, the detail of the hands in the second of the two biblical scenes, the one in which Esau is rejected by his father Isaac, deceived by his other son Jacob who wanted to obtain the rights of primogeniture with the complicity of his mother Rebecca. The hand of Esau holding a spoon with which he hands food to his father is made with the same spirit of observation and reproduction of the naturalistic datum that was previously noted in the hand of Christ nailed to the cross. Another happy comparison can be found by juxtaposing Christ's loincloth and the sheet of Isaac's bed: both have a strong materialistic rendering, achieved through skillful modulation of light. The latter element plays a key role: in both works it is used theatrically, despite the difference in composition. In the Stories of Isaac, in which we are confronted with a choral scene in which the protagonists stand on a stage, light floods the room recreated by Giotto, one of the most important innovations of Giotto's revolution, and helps to sustain its spatiality. In the Cross, on the other hand, light strikes the body of Christ, enhancing the individual figure. Comparing the face of St. John and that of Esau, it is possible to highlight another element of close similarity between the two depictions: in both, in fact, the same solution can be seen for the nose, made by means of a flat brushstroke accompanied by a sharp line of light.

It is figurative philology that tells us that it is the same hand that intervened in both situations. Once the Cross of Santa Maria Novella has been attributed to Giotto, supported also by the almost contemporary testimony found in the will of Ricuccio di Puccio del Mugnaio dated 1313, it must be acknowledged that the one who intervened in the Assisi worksite, producing the Stories of Isaac (for this reason often referred to as the Master of the Stories of Isaac) and later representations up to and including the Franciscan Stories, brought disruptive innovations in Italian painting, which will also condition the start of modern art, is Giotto, because the way of understanding and realizing painting (albeit with differences due to the context and the support employed) is similar in both works.

As far as the more specific chronology is concerned, the hypothesis has been put forward that the Cross was likely made between the frescoes of the Stories of Isaac and the beginning of the later cycle of the Stories of St. Francis. One can, for example, observe the close similarity between the Pained Virgin of Santa Maria Novella and some of the faces in the Franciscan Stories, particularly the weeping face of a woman in the episode of the Death of the Knight of Celano, the sixteenth of the twenty-eight scenes in the cycle: it is likely that a preparatory drawing was reused, and in this case it is safe to assume that the original was made for the sacred icon, the Cross. It is possible, therefore, to hypothesize assigning a chronological priority to the Florentine painting or at least to consider it roughly contemporary with Giotto's intervention in the Assisi worksite with the Stories of Isaac, advancing a proposed dating in the first half of the 1390s.