Pater Padus. On the great river a sunshine of art in San Benedetto Po: the Monastery, the Refectory, the Basilica, the Museum

San Benedetto Po is home to the Basilica of Polirone, a place with a history dating back thousands of years that holds invaluable art treasures.

By Giuseppe Adani | 09/06/2020 16:56

Solemn still flows the Pater Padus, lying in its great Emilia-Lombard basin. In the long journey for centuries it has reclaimed two venerable citadels of high prayer and untiring labor among the fields. To the song of the monk Guido, raised with his faithful choir from the distant Pomposa, has responded now son millennia the ardent worksite of works and studies of the Canossian stronghold that had as its name simply that of the founder of the new Christian and Roman civilization: St. Benedict. Among the bodingos and gunziaghe of the waters scattered south of Mantua, Tedaldo degli Attonidi since 1007 laid a human foundation capable of reclaiming, regimenting and building: a monastery that realized with almost unequaled power the triple rule of the saint of Norcia:ora, lege, et labora!

From the confluence of an ancient stream into the Po, the abbey was more extensively called San Benedetto in Polirone, and the specific title remains to this day, sometimes solitary: the Polirone! We say this for the curious traveler and the facilitating name that the inhabitants still use today, as do scholars and chroniclers. Historically, from Tedaldo to Bonifacio, and from Bonifacio to Matilda of Canossa, dynastic protection remained powerful and promotive: monks increased as the rustic expanse was gradually segmented by the network of ditches and sheep-tracks, fertilized by grains and fodder, dotted with small granges for the diuturnal prayers of fervent converts.

Matilda was a great mother for her Polirone as well: while cloisters were being articulated, while manufactures on products and the first scriptoria flourished, She with unspeakable care erected the august Chapel for her tomb, rich in marble and mosaics: small ecclesia for the adorned liturgies, so beloved by her and so sublime in the psalteric canticles. Shortly before her death, the Grand Countess performed the mutant act that grasped the monastery in a grandiose breath: she donated the entire foundation to the pope of Rome, and he aggregated it directly to the very heart of the Benedictines of Europe, that is, to the model-monastery of Cluny, the wonder of Suger! This abbot, an admirer of the beauty of creation, of its lights, of the colors of the heavens, brought to the architecture of the incipient Gothic the majesty of forms and the splendor of materials beginning with the stones themselves, from sculptures to stained glass, from mosaics to gems.

|

| San Benedetto Po.View of the center of the ancient monastery, now the heart of the town. Note Giulio Romano's Basilica, and on the far left the large Refectory, distinguished by the hanging arches. |

|

| Basilica of Giulio Romano (1545). The grand sweep of the nave, advancing "a serliane." |

|

| Cross-sectional view of the interior of the Basilica. Rhythm, spatiality and light, to the measure of Rome. |

|

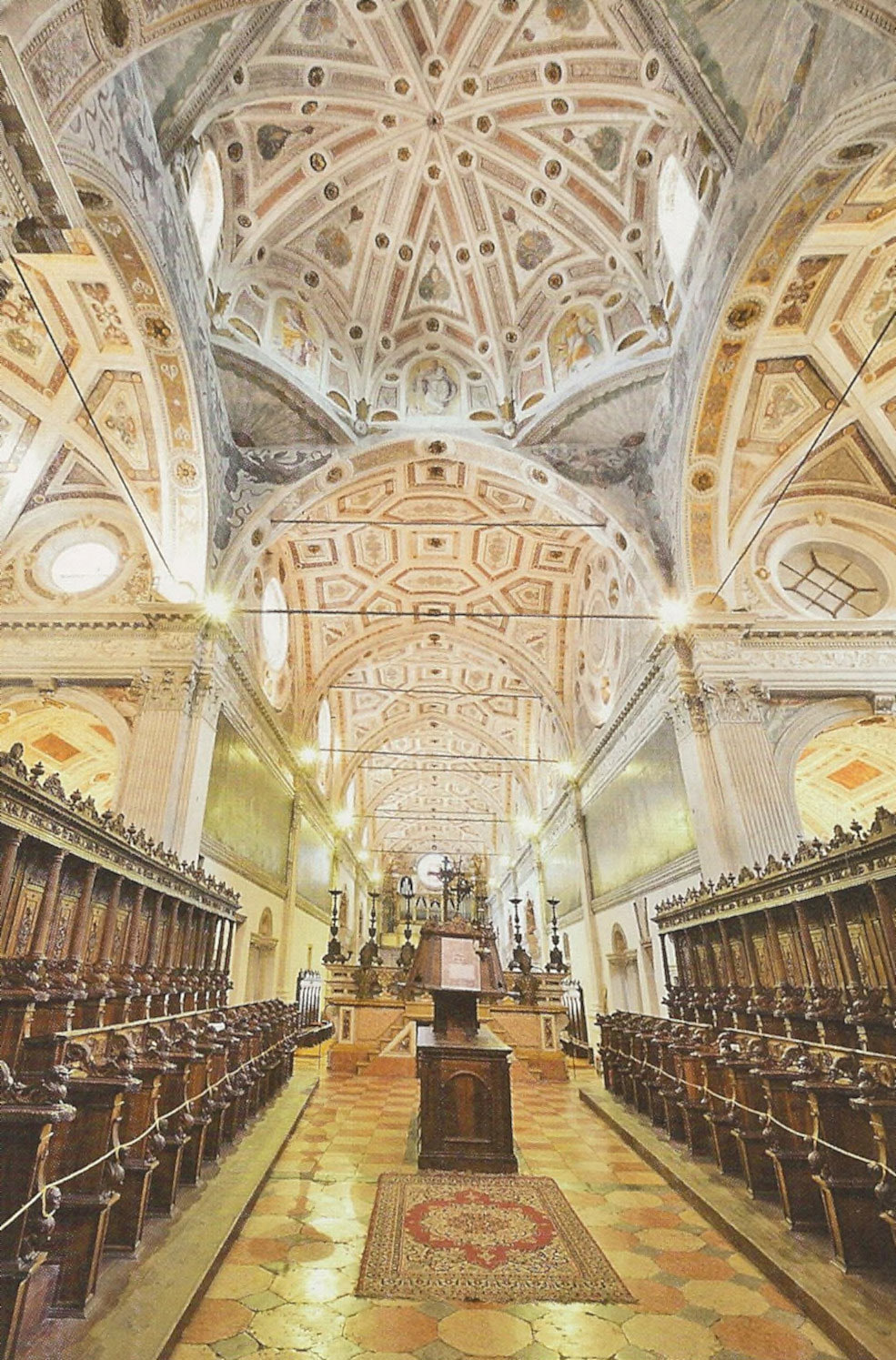

| The choir of monks behind the high altar. Note above the Mannerist decoration of the vaults. |

St. Benedict, strong among the waters, after having tamed the might of the river with his famous brushes, expanded into building works and above all devoted himself to study, to the multiplication of books, to philosophical and theological relations with the other realities of the Order and the whole Church, so much so that he became a cultural pivot, famous in Italy, and a meeting place for eminent personalities. Indeed, the site stood as the point of a valuable assisted ferry on the great river, as a stopover for the long journeys and pilgrimages of the late Middle Ages, as a stopover capable of guest quarters, infirmary, lodgings for humans and animals, and as a recreation of the soul through participation in religious life and the famous library. We mention it because in the late 15th century and early 1500s the flourishing of this monastery was specious. A German religious on his way to Rome, whose name was Martin Luther, also stopped there in 1510 and was well received.

Giovanni Andrea Cortese (1483 - 1548), born in Modena to a distinguished family, a prodigy student in law universities, personal secretary and friend of the young Cardinal Giovanni de' Medici in Rome, and already a priest, suddenly wanted to take a turn in his life: in 1508 he professed at St. Benedict's, far from the noise of the world, taking the name Gregory. His exceptional personality did not allow him the desired total concealment, and the monks soon elected him Cellerarius (i.e., deputy abbot and administrator) such that he had to lead the strong numerical and building expansion of the community in a period of long absence of the titular abbot. He learned to know a talented young painter, Antonio Allegri, who willingly stopped for several days at the Polirone on his travels between Correggio and Mantua, wanting to study many things and showing himself to be very applied to biblical history, theology, architecture, and the various sciences all fermenting in the cloisters.

That young man would later be known as Correggio (1489-1534) after the name of his birthplace. In 1513 Gregory took him to Rome, where his friend John, now Leo X, had just been elected pope. Antonio sees and collects all the artistic signs of antiquity and carefully visits the works of Michelangelo (the Moses, the Prisoners, the biblical vault of the Sistine Chapel), Raphael (the Sibyls at Santa Maria della Pace, the first two Vatican Stanze, the Madonna of Foligno), and sees again the Bramante already observed in Milan, who here had begun the huge new St. Peter's with the eveniente problem of placing a very large dome high above the arches: a problem about which, because of its boldness and weight, there had already been heated debate. Correggio studied early Christian monuments: the Mausoleum of St. Constance, the Lateran Baptistery, St. Sabina, and others by checking their members and articulations. He also turns to imperial architecture in its most developed trials, such as the Pantheon, and such as the Severian Septuagint, where the columns rose to an elevating task of special significance. All this because on her return a test awaited her that Raphael, citing insuperable reasons, had graciously refused to dear Abbot Cortese. It was to give the new Refectory a magnificent apparatus painted on the front wall as the setting and glory of the divine Eucharist, the true food of souls.

The Refectory is still a monumental room, and was connected to the cloisters, preceded by the Fountain for purification. At the end of the long, high hall the monks had wanted a depiction of the Last Supper, a sign of the divine food as a sacrament instituted by Jesus as an offering of himself before the Passion. For such a scene they had turned to a painter, the Dominican converso Girolamo Bonsignori, in order to have a large replica of Leonardo's Last Supper, considered unsurpassed as an image. Now that highly prominent canvas, executed in the very early years of the 16th century, after long travails and a recent restoration has returned to its shining place where it will remain for these months of 2020. Correggio's trip to Rome thus yielded the spectacular creation of an emblematic architecture, stretched across the entire wall surface, which responded to a profound theological disposition, elaborated by Cortese and congruent with the entire spiritual climate of monastic life. According to that disposition, the offering of the Eucharist stands at the center of the two great cycles of time: that of expectation, from creation to the Incarnation of Jesus, and that of Grace, which we are experiencing after Redemption. Correggio's fresco thus assumes the first role, that of the biblical time of the Old Testament, where the Jewish people explicitly awaited the promised Messiah, but where pagan peoples also in a mysterious and intuitive way lived the same salvific expectation.

|

| Full view of the front wall of the Refectory. Correggio's drafting of the solemn classical temple, of extraordinary architectural conception, contains under the central dome the Last Supper, copied by Girolamo Bonsignori at the Convent of the Graces in Milan, the work of Leonardo. The temple represents the ancient age. |

|

| The very accurate gold capitals, created and painted by Correggio. Here the overlook of the Barbarian Priest, braced. |

|

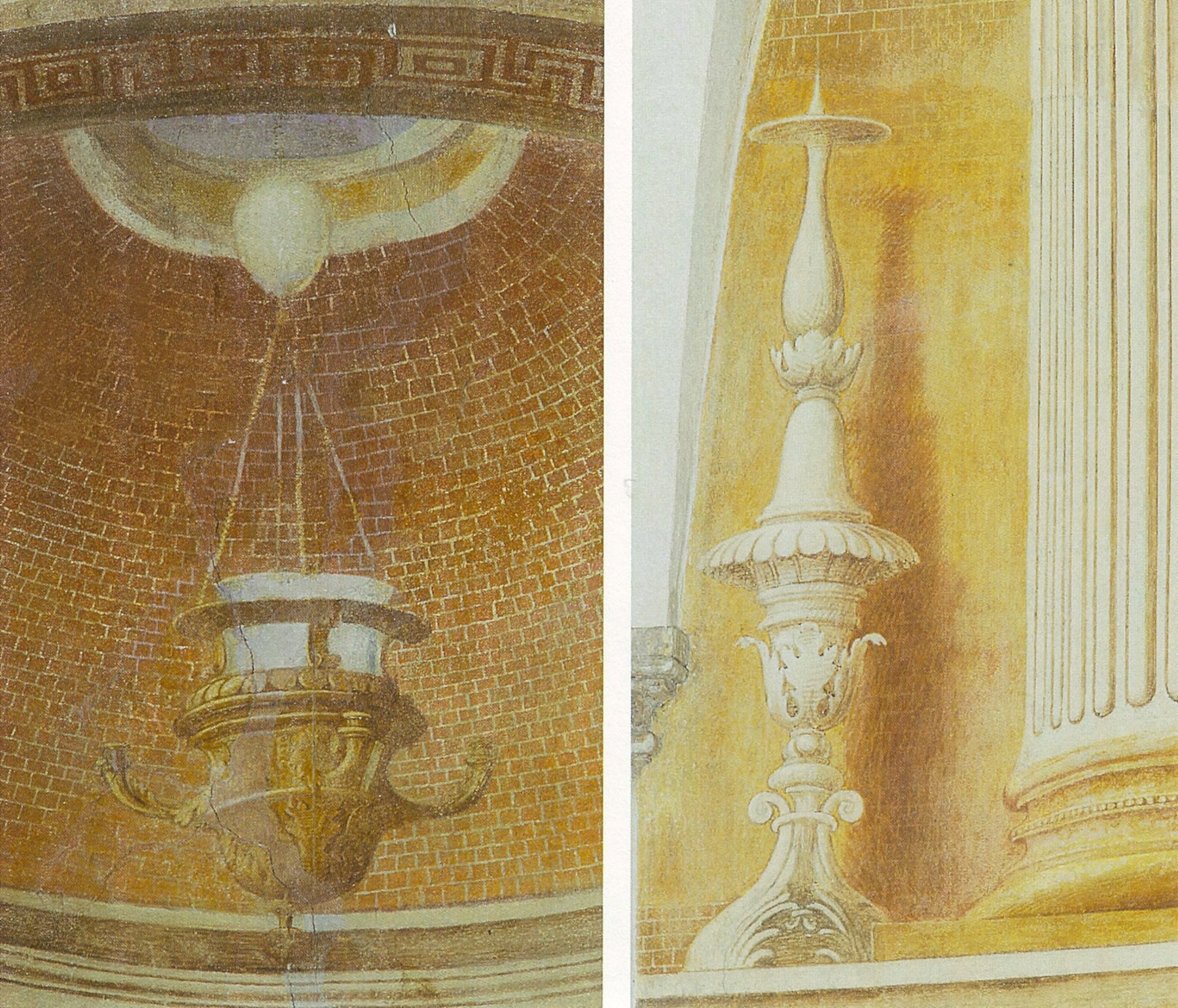

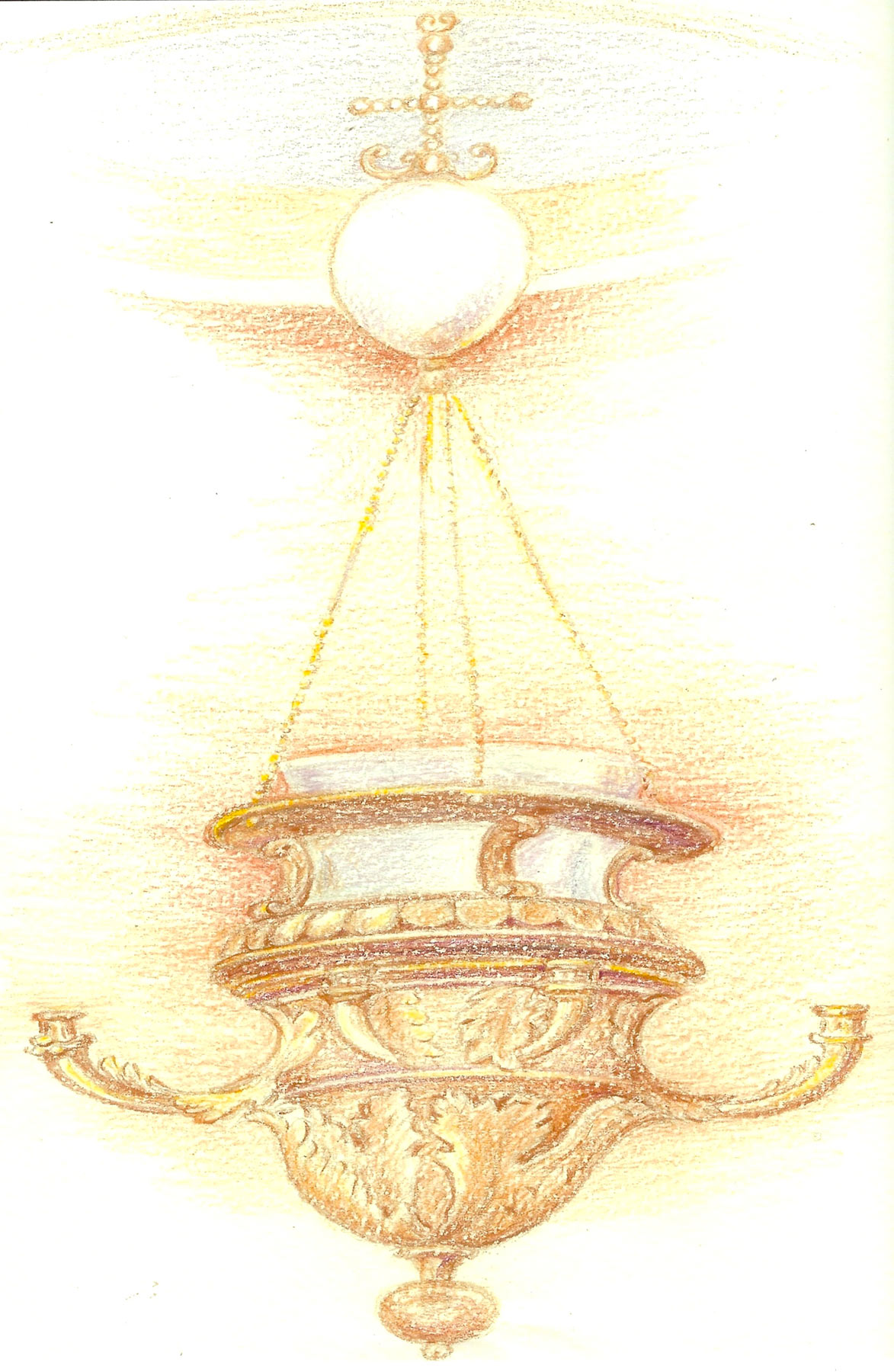

| The lamp, descending directly from heaven. The very elegant candlestick, mindful of Perugino's stylism. Both of these presences bring back the refined goldsmith culture of Antonio Allegri. |

|

| The relief of the lamp, taken on the scaffolding by Renza Bolognesi, confirms Correggio's extreme attention to the finest details, such as the pearl cross above the mystic egg and the very fine chains. |

The close consonance between the painter and Gregorio Cortese made the painter choose the pictorial realization of a solemn temple observed through a perspective coming from a distant horizon, which brought the Supper of Jesus to the center of the two time cycles: that is, between prophetic antiquity and the living monks in the abbey who were fed here. Correggio'sinventio is expressed in an admirable vast architecture seen from below and in central fugue, articulated in an all columnar system of the Corinthian order bearing the progressive and transverse vaults, serranti two majestic domes: the one further inward open to the sky whence descends the lamp of Light, and the imminent one (optically presumptive but real) covering ad umbraculum the apostolic table. This stupendous architecture, high on the podiums and inexperienced in comparison with all the projects of the Renaissance, can be translated and lèread perfectly in plan as is never possible for other painted membratures. A true embrace of the soul that comes from the young Correggio (1513-14).

In order to understand this fresco, an invigorating guide is needed, leading first through creative thought and gradually punctuating the encounters in the solemn temple of the Old Testament. On the viewer's left side are the events of the chosen people, the Jews, through their Mothers, the prophets and the song of David; on the right side (which is the divine left) are the pagan peoples, from the barbarians to the classical Greeks (with the beautiful Hellenic Sibyl), to the Romans who are presented with Virgil, the great Mantuan poet who from the Georgics raises his song of the longing for a Messiah. Correggio's figurations are complemented, using a beautiful monochrome, in the two episodes that ideally clamp together the Eucharistic consecration of Jesus at the Last Supper: on the one hand the Sacrifice of Abraham and on the other the sublime offering of Melchizedek, priest of God Most High, albeit "Gentile" (i.e., non-Jewish), who presents the bread and wine to the Eternal One for supreme honor !

|

| Abraham's sacrificial offering and Melchizedek's mystical offering flank the Lord's Supper. |

|

| Detail of the sacrifice of Isaac. Here the unmistakable hand of Correggio appears in the inexhaustible hatching. |

This is the magnificent Refectory, which in the past winter months hosted an excellent Exhibition perfectly linked to the Year of Giulio Romano, celebrated above all in Mantua, but which in San Benedetto was able to offer the majestic, splendid architecture of the Abbey Basilica, due precisely to Raphael's great pupil and his only monumental project of a religious nature. Here Giulio found an ingenious solution of structural and even urbanistic insertion, moving around his membranes and the capturing of a vast light a host of truly exceptional collaborators. The exhibition and the catalog were masterfully curated by Paolo Bertelli, with the collaboration of Paola Artoni, and contributions from various well-known scholars. Bonsignori's canvas was loaned by the Municipality of Badia Polesine, where secular events took it, and quai all the important pieces now remain in their usual locations, in the Basilica and in the Museum, so that the visitor can fully rediscover the marvelous and overall climate of 16th-century art, without losing the enchanting legacies of Matilda of Canossa.

The visitor (pilgrim, or scholar, or art lover) is first greeted by the quiet village, lying among the peaceful fields, and enters that dimension so truly human that it still carries the cadence and breath of the monks, as Giovanni Pascoli sang: hic sata pascua villae (here sowings, fields and villas), and even more: the honey, the wine, the fruits, the elaborate products of agriculture and animal husbandry (the cheeses, the mustards, the first courses with stuffed pastas, the sweet cakes). And then the vision of the four cloisters whose itinerary is always exciting, the silent Romanesque little church of Matilda with its vivid mosaics, the Basilica, very rich in every point (as if we were in Rome someone said) with the superb architecture by Giulio Romano, the thirty-two statues by Begarelli, the paintings by Ghisoni and other masters from Mantua and Verona, the magnificent choir, the famedio of Matilda herself, and finally the Sacristy which is a true monument of the mature Renaissance.

Therefore, a note of hospitality is important for those who would like to take themselves happily to San Benedetto Po. Behold, one must immerse oneself in this totality that is the mirror of our human life, made up of spirit, of waiting for blissful eternity, and of corporal nourishment in bonum animae: that is why the Polirone's trattorias and Achilles' wine will also leave a beatifying memory.

|

| The front of Giulio Romano's Basilica as it appears today after the central elevation of the 1700s. |

|

| Detail of the head of Santa Giustina, by Begarelli. From here one can grasp the wonder expressed by Michelangelo on the Po Valley plasticator. |

|

| Giuseppe Turchi (18th cent.). The consecration of St. Nicholas as bishop of Mira. One of the many paintings of which the Basilica is rich. |

|

| Famedio of Matilda of Canossa as it was composed in the 16th century. The Great Countess was buried here, first in a Romanesque mound. In the 17th century she was moved to St. Peter's in the Vatican. |

|

| Sacristy of the Basilica del Polirone. Partial view. The room is most solemn, designed entirely by Giulio Romano and enriched by the stupendous cupboards by Giovanni Maria Piantavigna (1563), already the author of the choir. |