One of the leading artists of the Italian Renaissance, Andrea Mantegna (Isola di Carturo, 1431 Mantua, 1506) was long active in northern Italy and is known to have spread an antiquarian culture based on the observation and evocation of classical antiquity. His characteristic rugged mark-making and the almost statuesque monumentality of his figures derived from this interest, and in addition his frequentation in his youth of the fertile humanistic environment of Padua soon brought him into contact with the novelties of the early Renaissance: observing the works of Donatello he was able to learn to master the perspective construction that became another stylistic feature of his art, to the point of enabling him to create a masterpiece such as the Bridal Chamber, the most important and challenging masterpiece of perspective illusionism of the 15th century in Italy.

Not many of Andrea Mantegna’s works(you can learn more about the artist at this link) remain with us: some of them are still in the places for which they were conceived, while others are preserved in museums around the world. There are several Italian cities where Mantegna’s masterpieces can be admired. In this article we propose a tour through eleven Italian cities, from north to south, where works by the great Venetian artist are preserved. A sort of Mantegna Grand Tour to get to know everything about Mantegna that is preserved in Italy. From Padua to Naples, from Mantua to Florence, here are the cities where to see the works of Andrea Mantegna!

The journey begins in Padua, for at least two good reasons: first, because it is the city where Mantegna was trained (in the workshop of Francesco Squarcione), and second because his first important work, the fresco decoration of the Ovetari Chapel in the Church of the Eremitani in Padua, is located here. Consider that at the time he was given the commission, in 1448, Mantegna was still a minor, and it was his older brother Tommaso, as his guardian, who signed the contract for the frescoes: the artist frescoed in two phases the Stories of St. James (an undertaking in which Nicolò Pizzolo would later also participate) and the Stories of St. Christopher (the latter begun by Bono da Ferrara and Ansuino da Ferrara): it is Mantegna’s responsibility to create the entire north wall (the one with the Stories of St. James), while on the south wall the Martyrdom of St. Christopher and the Transport of the Beheaded Body of St. Christopher are his. Mantegna’s frescoes were unfortunately severely devastated during World War II; today we can see their fragments but we know very well what they looked like before the destruction because we preserve excellent photographs. Also in Padua, the Museo Antoniano preserves a Trigram of Christ between Two Saints from the lunette of the central portal of the Basilica del Santo in Padua, another early work, dating from 1452.

Shortly after completing his work in Padua, Mantegna was called upon by the abbot of San Zeno in Verona, Gregorio Correr, who entrusted him with the creation of what would later become one of the most important works of the Renaissance, the San Zeno Altarpiece(read more about this masterpiece here). With its new conception of space and its monumentality derived from the study of ancient art, the San Zeno Altarpiece, executed between 1457 and 1459, effectively kicked off the Renaissance in Verona. The work can still be admired today in the basilica of San Zeno. Also in the Venetian city, the Museo di Castelvecchio houses a mature work, a Holy Family dated 1495-1505. The work is among the paintings that were stolen on November 20, 2015, from Castelvecchio during one of the most sensational art thefts in the past two decades, and was found, along with all the others, the following year.

Mantua is perhaps the quintessential Mantegna city since it is home to Andrea Mantegna’s most famous work, the decoration of the Bridal Chamber, which is located inside the Castle of San Giorgio, now part of the Doge’s Palace tour itinerary(read a detailed discussion of the Bridal Chamber here). It is a cycle of frescoes executed between 1465 and 1474 for what, despite its name, was actually a room reserved for audiences. The entire decoration of the room redefines the real architectural space by extending it and plunging the visitor into a place that seems to be much larger than it actually is: perspective illusionism (just look at the extraordinary oculus), fake bas-reliefs, and stuccoes transport us to a place where reality and fiction have very thin boundaries. On the north wall we see the depiction of the court of Ludovico Gonzaga, who had been trying to call Mantegna to Mantua since 1456, later succeeding in the 1960s. On the west wall, on the other hand, here is the meeting between Ludovico and Francesco Gonzaga, while the other two walls are adorned with garlands, coats of arms, and Gonzaga enterprises. The Mantuan tour does not end with the Ducal Palace: in the basilica of Sant’Andrea is in fact the chapel of Mantegna, the place of his burial: here it is possible to admire the Holy Family and the Family of the Baptist and the Baptism of Christ, two tempera paintings that adorn the room.

Although Mantegna never worked in Milan, many of his masterpieces are preserved in the city. At the Pinacoteca di Brera you can admire the Polyptych of St. Luke, an early masterpiece (1453-1454) painted for the Abbey of Santa Giustina in Padua, as well as what is probably Mantegna’s best-known mobile work, the Dead Christ(here an in-depth look at the work). Also at Brera is the Madonna and Child with a Chorus of Cherubs, from about 1485. At the Castello Sforzesco is a masterpiece of his maturity, the Pala Trivulzio originally executed for the church of Santa Maria in Organo in Verona, and finally the Museo Poldi Pezzoli holds a Madonna and Child known as the recently restored Poldi Pezzoli Madonna(read more about it here, and a much-discussed Portrait of a Man of uncertain attribution.

Mantegna stayed at least a couple of times in Ferrara, where he worked for Leonello d’Este and Borso d’Este. Nothing remains of his Ferrara activity in the city (the little that has survived has taken other destinations), but at the Pinacoteca Nazionale it is possible to admire a Christ with the Animula of the Madonna, which belongs to the altarpiece of the Death of the Virgin, now in the Prado, and originally painted for the private chapel of Ludovico III Gonzaga in the Castle of San Giorgio in Mantua.

Florence is another of the cities visited by Mantegna, who sojourned there between 1466 and 1467 (the artist had relations with Lorenzo the Magnificent). Perhaps here the artist painted two of his masterpieces that are now in the Uffizi, namely the Triptych of the Uffizi, a work from the 1460s that, however, does not appear in documents until 1587, when it is mentioned, dismembered, in a location near Pistoia, in the collections of Don Antonio de’ Medici (we do not know, therefore, when the work was made: perhaps, it was painted for the Medici themselves), and the Portrait of Carlo de’ Medici, the natural son of Cosimo the Elder (for this work, too, we do not know the circumstances of its making). Finally, the Uffizi houses a third work, the Madonna delle Cave, which was already in the Medici collections in Vasari’s time.

The Venetian artist was never in Naples, but the vicissitudes of collecting brought two of his important works to the Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte: a youthful canvas, the Saint Euphemia, of which, however, there is no record until the nineteenth century (the similar setting to that of the frescoes in the Ovetari Chapel, however, makes it considered a work of the period), and the famous Portrait of Francesco Gonzaga, datable to the early 1960s, which came to Campania with the collections of the Farnese family, who owned it as early as the seventeenth century.

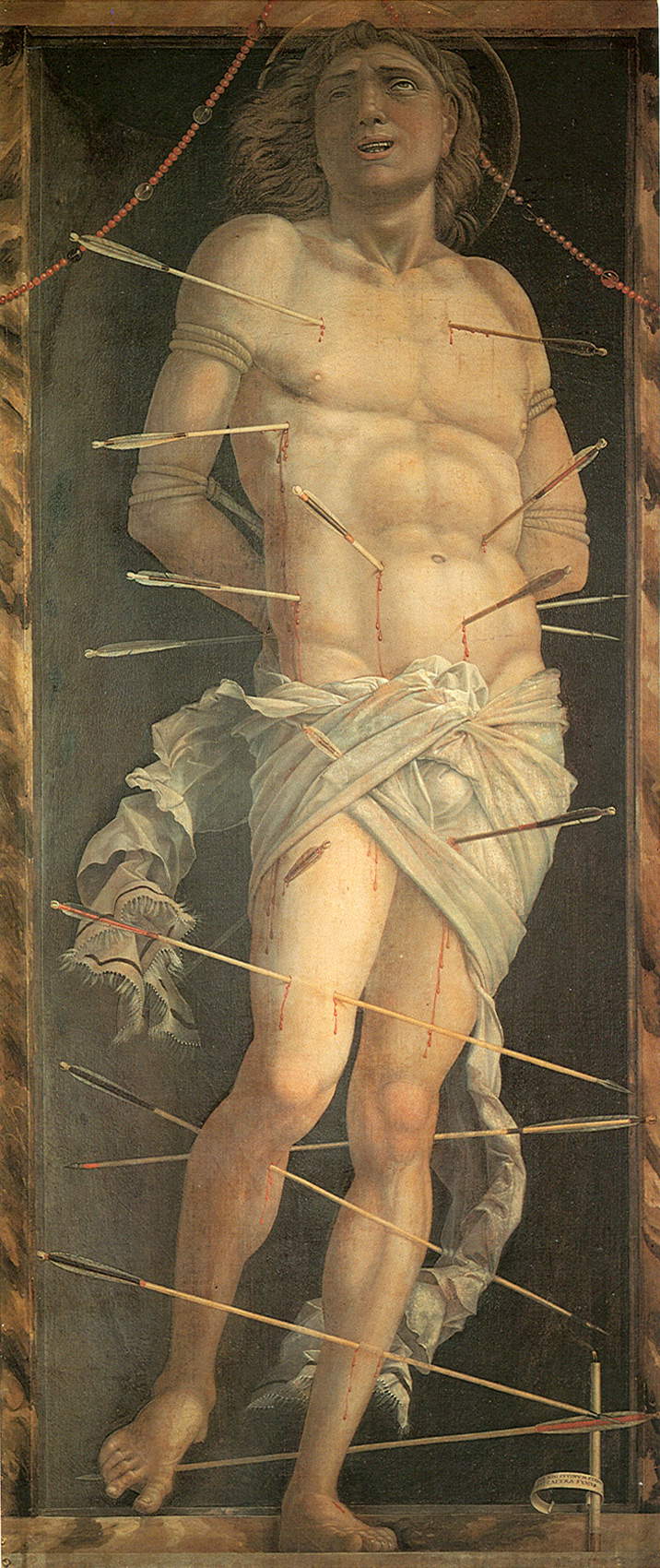

There are also two Mantegna works preserved in Venice: the earliest is a St. George, datable to about 1460, which is preserved in the Gallerie dell’Accademia, a work still of Squarcionesque influence, and therefore a youthful one. The other, far more famous, is the St. Sebastian in the Franchetti Gallery at the Ca d’Oro, a painting attested to the mid-sixteenth century in Pietro Bembo’s house in Padua (the scholar Marcantonio Michiel reported seeing it there). In 1810 Bembo’s heirs sold it to the surgeon Antonio Scarpa, and the latter’s heirs in turn in 1893 sold it to Baron Giorgio Franchetti: since then the painting has never moved from the Ca d’Oro, donated to the City of Venice in 1916 with its entire collection (Giorgio Franchetti moreover considered the St. Sebastian to be the most valuable work in his collection, to the point of commissioning the construction of a special chapel to house it).

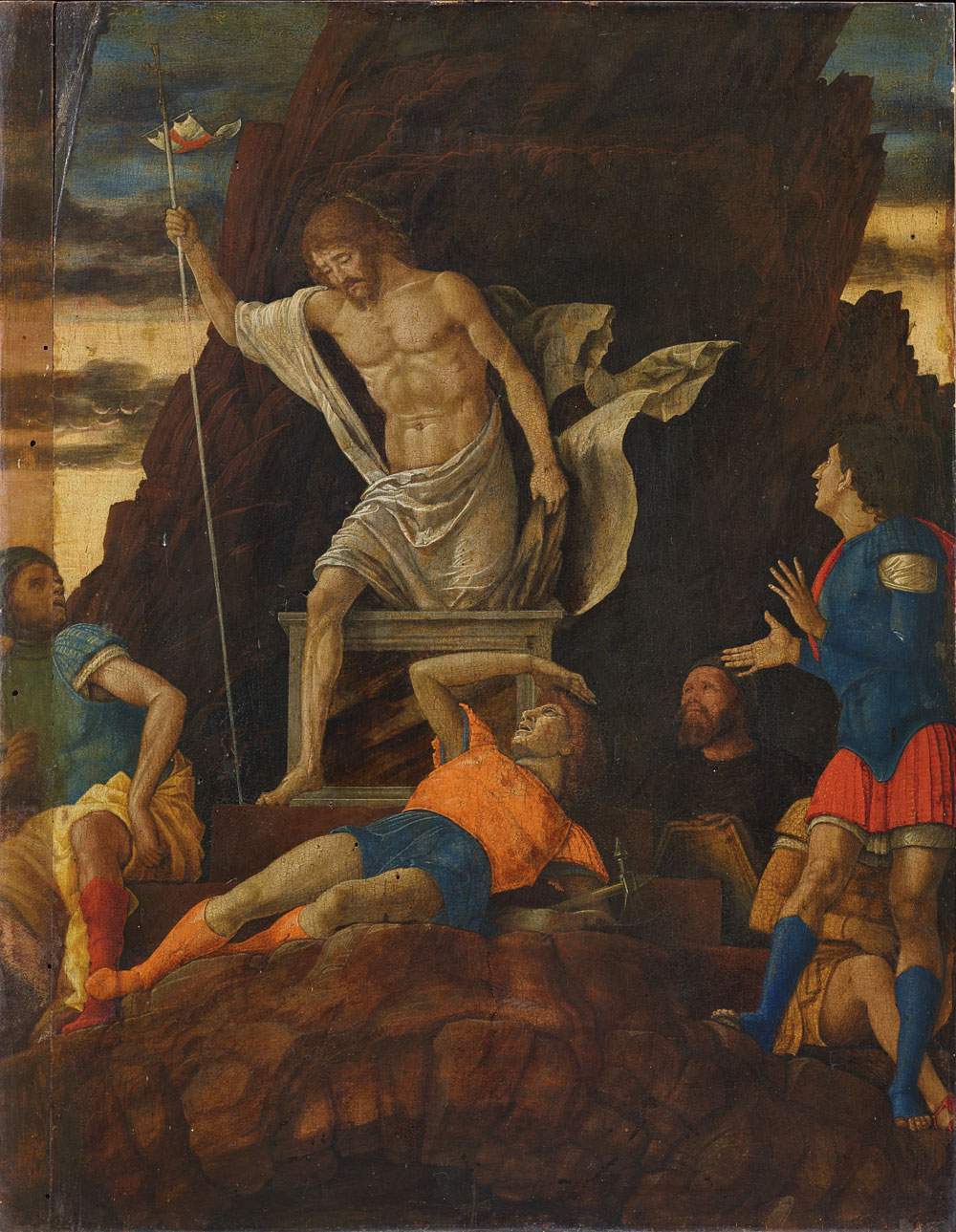

Two works by Andrea Mantegna are also in Bergamo, both housed at the Accademia Carrara: the first is a Madonna and Child from the 1590s, while the second is the most recent acquisition in Mantegna’s catalog. It is the Resurrection that was “discovered” in 2018: indeed, it was thought that the work was from the workshop or an artist of the circle, but recent studies have identified a detail of the painting that places it as an indisputable autograph, and in particular as the upper part of the Descent to Limbo executed by the artist in 1492 and now preserved in a private collection.

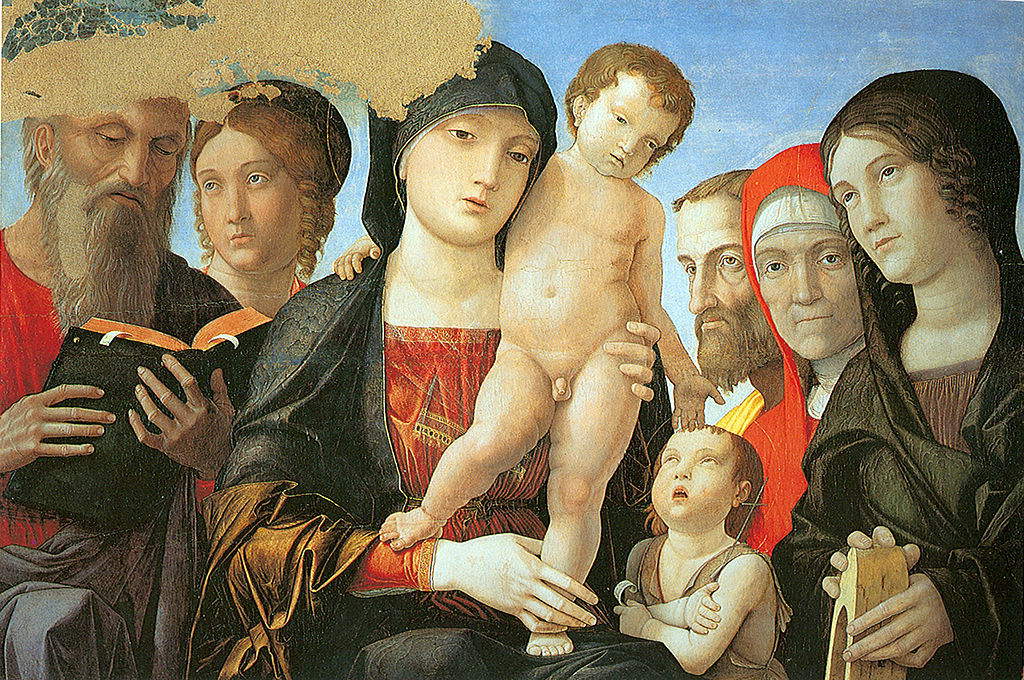

Turin also has a work by Mantegna, a Madonna and Child with Saints, from 1500, which is in the Galleria Sabauda, now part of the Royal Museums. The painting is badly damaged in the upper left part. We are not sure how this painting came to Piedmont, but it has probably been in the area since the 16th century, since a painting copying this composition dates from that time.

The trip ends at the “Il Correggio” Museum in Correggio, where there is a Christ the Redeemer painted in oil on linen canvas (it is painting number 1 in the Emilia museum’s inventory). The work was published at the end of the 19th century by Gustavo Frizzoni and has been in Correggio since 1917 (it was owned by the Congregation of Charity, which then gave it to the Municipality of Correggio). The Congregation received it as an inheritance from a local noblewoman, Caterina Contarelli: however, it is not known how the Christ came to be in her collection, although it is assumed that it must have been in the family collections since the seventeenth century, at the time when Giulio and Francesco Contarelli administered the finances of the small principality of Correggio (there is no evidence for this, however). Following critical debate, the work, between the 1950s and 1960s, became a permanent part of the catalog of Mantegna’s autograph works.

|

| Where to see Andrea Mantegna's works in Italy. Journey through 11 cities |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.