Unusual and little-known Sardinia: 10 places to discover

Hidden among the turquoise waves of the sea and sculpted by the strong wind, stands wild and guardian of raw legends, the island of Sardinia. A land, this one, that possesses an untamed beauty, where the waves crash with unprecedented force against the rocks, where white beaches hide among small inlets and where the soul is freed in theembrace of the sea and the breath merges with the rhythm of the wind. Deep in the island, ancient ruins tell the story of peoples who inhabited these lands centuries ago, where mysterious nuraghi stand like sentinels of the past. Every stone, every wall, holds the memory of a history thousands of years old. The tales of shepherds and fishermen become legends passed down from generation to generation, and ancient arts, such as weaving and wrought ironwork, are transformed into true works that enchant the senses.Here, time flows differently, it seems slower and fiercer, clinging to the flesh forcing the adventurer to live intensely every moment, but it is in the dense interweaving of culture and tradition that the island reveals its deepest and most mysterious spirit, and it is precisely for this reason, that to truly know Sardinia, one should break away from the crowded beaches and venture into the most secret streets. Before delving into these lands it will be necessary, however, to make the traveler aware of the fact that in Sardinian a sound is often used, similar to the French “J,” which does not exist in Italian, which in the island is written as “X” and read as ji (/Ê’i/): it will often be found in the ten unusual and little-known places in Sardinia that we are going to discover.

1. The residence of the cursed count: the Castle of Acquafredda

“La bocca sollevò dal fiero pasto / quel peccator, forbendola a’ capelli / del capo ch’elli avea di retro guasto.” With these words Dante Alighieri began Canto XXXIII of the Inferno, making immortal the tragic agony of Ugolino della Gherardesca, accused of treason and left to starve to death along with his sons Gaddo and Uguccione and grandsons Nino and Anselmuccio by order of Archbishop Ruggieri. In lower Sulcis he is called “the cursed count” because he was the owner of Acquafredda Castle from 1257, and it is here, within the walls of the fortified medieval-era structure, that the majestic “torre de s’impicadroxiu,” the tower of the hanged man, stands out, where, in all likelihood, Vanni Gubetta, one of Count Ugolino’s traitors, was imprisoned. The architecture of Acquafredda Castle is a masterpiece of defensive engineering articulated on three harmonious levels that follow the natural course of the Cixerri valley on which it stands. After Ugolino’s death in 1288, the castle came under the aegis of Pisa and later to the Aragonese in 1324, and over the centuries, it changed ownership several times until Victor Amadeus III of Savoy redeemed its possession in 1785.

2. Carbonia, the coal town that must not die

“Carbonia must not die” read a phrase written on the walls of Via Fosse Ardeatine. And it is true, Carbonia must not die, however, the evil from which this city suffers is not of today, but was born with it in 1938, in an era that frightens and that one would like to forget. Founded during the fascist regime for coal mining, the town has emerged as a symbol of hard work, and its history shows how determination can overcome any obstacle. Right here, in the now unused Serbariu mine, the coal museum has been built: a cultural center where the secrets of the extremely hard and often deadly work that accompanied the town for decades are revealed. Visitors, accompanied by a guide, will be able to wander through the cramped and hot underground tunnels exploring the depths of an industrial past. A museum, this one, that plays a fundamental role in preserving the memory of an era that left an indelible imprint on the city of Carbonia and its people.

3. The archaeological area of Su Nuraxi.

During the 1940s, archaeologist Giovanni Lilliu, discovered and brought to light the archaeological area of Su Nuraxi, which takes its name from the island’s best-known buildings, namely the nuraghi. The Nuragic civilization flourished through a time span of about a millennium, between 1500 and 500 B.C., giving rise to an intricate and extremely sophisticated social web, and su Nuraxi bears witness to precisely its constant change over the millennia, from dwellings to urban life. The Barumini site dates back to the Bronze Age (1900-730 B.C.) and was built on high ground overlooking the surrounding plain. It consists of a series of stone buildings, including the central nuraghe, a tholos tower, four perimeter towers, and a wall. Originally intended to house a single family, over time the central body was encompassed by four more towers and finally by a wall, becoming a fortified village. A place, this one, still shrouded in mystery, but which, despite everything, has left the most precious legacy of a civilization of which we still have much to discover.

4. The church of Saccargia

Wandering among golden fields and rolling hills the most curious of travelers might come across the lonely basilica of Saccargia: a fascinating religious building, located near Codrongianos. Mention of the basilica among the possessions of the Camaldolese monks dates back to 1112, and its story tells of Constantine I of Torres and his wife Marcusa, who, after a pilgrimage to the basilica of San Gavino in Porto Torres, were inspired by a sacred apparition to build this temple that was consecrated in 1116. The area, initially known as Sacraria, carries echoes of ancestral cults and devotion. Legend, like a thin thread woven through time, tells of a s’acca argia, “spotted, spotted cow” that knelt before the monastery, offering its milk to the monks as a sign of prayer. The church, which has a longitudinal basilica layout in the shape of a commissa cross with semicircular apses, is today a harmonious blend of styles and influences, a journey through the centuries that is revealed to visitors’ eyes. The basilica is composed of two distinct building styles: the walls in white limestone and dark basalt cantonettes, slightly rough-hewn representing the work of Pisan craftsmen in the late 11th and early 12th centuries, while the regular bichromatic work is attributed to the Pisan-Pistoiese sphere in the later 12th century.

5. The castle of Burgos

It is said that within the walls of the castle of Burgos, dwells a gigantic and terrible being who in life was an invincible warrior who arrived in Sardinia during the period of Spanish rule. For years he slaughtered Sardinian peasants for no apparent reason, and after his death his soul continued to roam the castle walls, fueling many macabre folk legends. And so it is that the castle of Burgos, thanks in part to its sheer location on a granite boulder, remains shrouded in a strange aura of mystery to this day. Its majestic structure was built in 1134 at the behest of Gonario I of Torres and from here on was the stage for ferocious murders. It was considered one of the best-protected manors in Sardinia thanks to its triple walls made of granite blocks and at the center of which rises, even today, a 16-meter tower that sees all.

6. In search of Maria Lai in Ulassai

Beyond its spectacular natural beauty characterized by extremely deep gorges, difficult-to-climb mountain walls and underground caves, Ulassai was the birthplace of artist Maria Lai, who transformed it into a theater for her art. Amid mountain landscapes and the majesty of the gorges, stands the Art Station: a place that embodies artistic inspiration and connection to unspoiled nature. Inaugurated in 2006, following a donation of more than one hundred and forty works by Maria Lai, the museum now stands in the former railway station downstream from the village, lashed year-round by a very strong wind. The choice of location lends itself well to communicating one of the most cherished intentions of the artist’s work, which is to bring art closer to people.

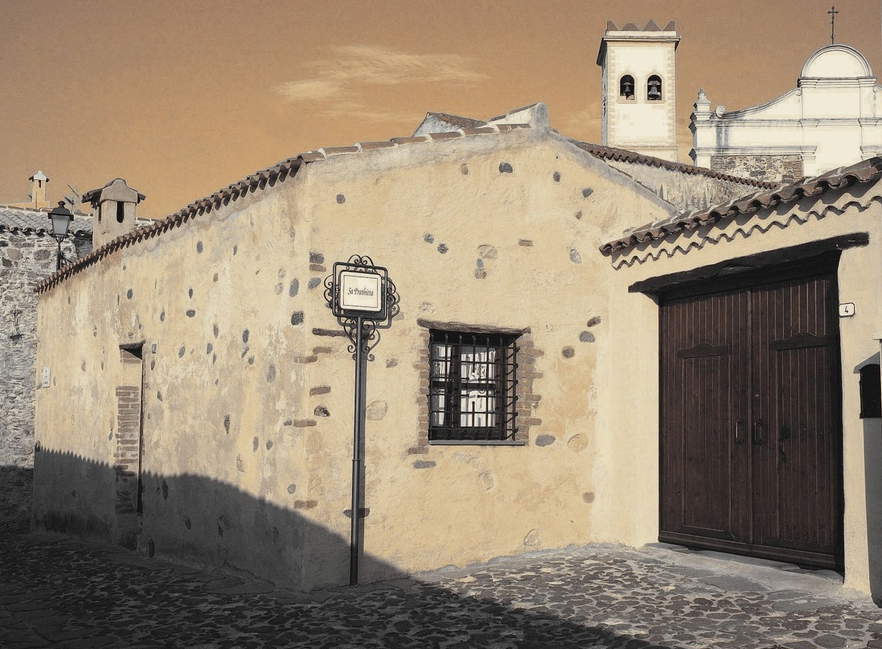

7. Galtellì, the charming village of Grazia Deledda’s tales

Galtellì, a charming village located in the Baronia region, is the setting for the novel “Canne al Vento,” Grazia Deledda’s best-known work. In this place, the writer spent time at the dwelling of the Dames Pintor, of whom she provides a detailed description in her book. In the context of the village, Deledda mentions the striking Monte Tuttavista, the evocative ruins of the Castle of Pontes, and the lovely Church of San Pietro, in the Pisan Romanesque style. Inside the basilica, one can admire splendid frescoes created by Umbro-Latian artists and precious wooden statues from the Sardinian and Neapolitan art schools. The writer speaks of it this way: “The basilica was crumbling; all around reigned a gray, damp and dusty atmosphere: through the openings in the wooden roof filtered rays of silver dust that descended on the heads of the women kneeling on the ground, while the yellowish-toned figures emerging from the cracks in the paintings hanging on the walls looked like these women dressed in black and purple...”

8. The natural monument of the Su Gologone springs.

Nestled between two high walls of dolomite rock, the springs of Su Gologone, branch out from the bowels of Supramonte and find light, at the foot of Mount Uddè, through a large fissure of emerald-colored water. The spring waters come mainly from the Supramonte of Oliena, Orgosolo, Dorgali and Urzulei. Over the millennia, various rivers have carved their own riverbeds into the depths of the Earth, forming a dense network of caves leading to the spring. This underground tunnel has been studied since 1999, years in which speleologists from the Sardinian Speleological Federation injected a non-toxic dye into the underground end to understand its flow and, after a month-long journey through the heart of the Supramonte, re-emerged from the source of Su Gologone. In this way it was discovered that the small lake embedded in the rock is the end of a very long underground river, where water and light finally meet for the first time.

9. The murals of Orgosolo

An extraordinary example of how art is a powerful medium for storytelling, preserving history and creating a deep connection between past and present is Orgosolo. Each mural is an opportunity to color the world with emotions, reflections and a sense of belonging, giving the village a unique artistic identity. This form of artistic expression unites contemporary art with the historical and cultural fabric of the region, offering a unique perspective on the daily life, hopes and challenges of its inhabitants, creating a window into the history of Sardinia. Born out of political protest in 1969, the paintings today also tell stories of hope, beauty, or give body and color to quotes and songs by great personalities in love with this strange island such as De Andrè.

10. De Andrè’s house.

Singer-songwriter Fabrizio De Andrè was a great lover of the Sardinian lands, and despite his kidnapping at the hands of the anonymous kidnappers, in which he experienced moments of terror at “the Supramonte hotel,” he never stopped inhabiting this little corner of his paradise on earth, but rather strengthened his bond with it. It was 1975 when Fabrizio De André and Dori Ghezzi bought the Agnata estate, at the time it was nothing more than a semi-abandoned “stazzu,” but the two of them resided here from the start, even without doors and lights so much was their love for the land. The singer-songwriter chose Agnata to fulfill his childhood dream when his family saved him from the war by fleeing near Asti. At his grandmother’s house he learned to love the land and all that comes from them so strongly de decide that, sooner or later, when he grew up he would have a place in the world of his own.

|

| Unusual and little-known Sardinia: 10 places to discover |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.