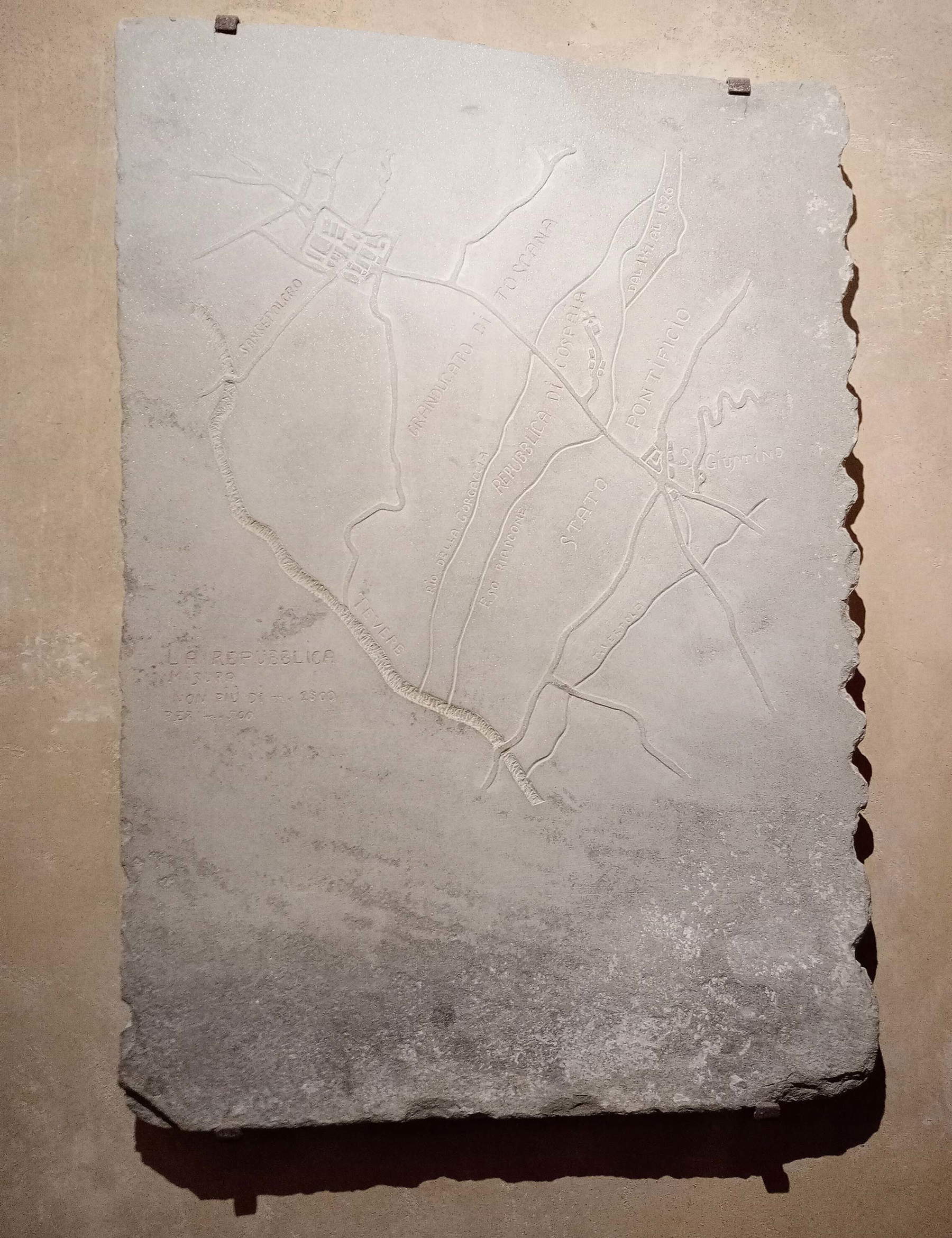

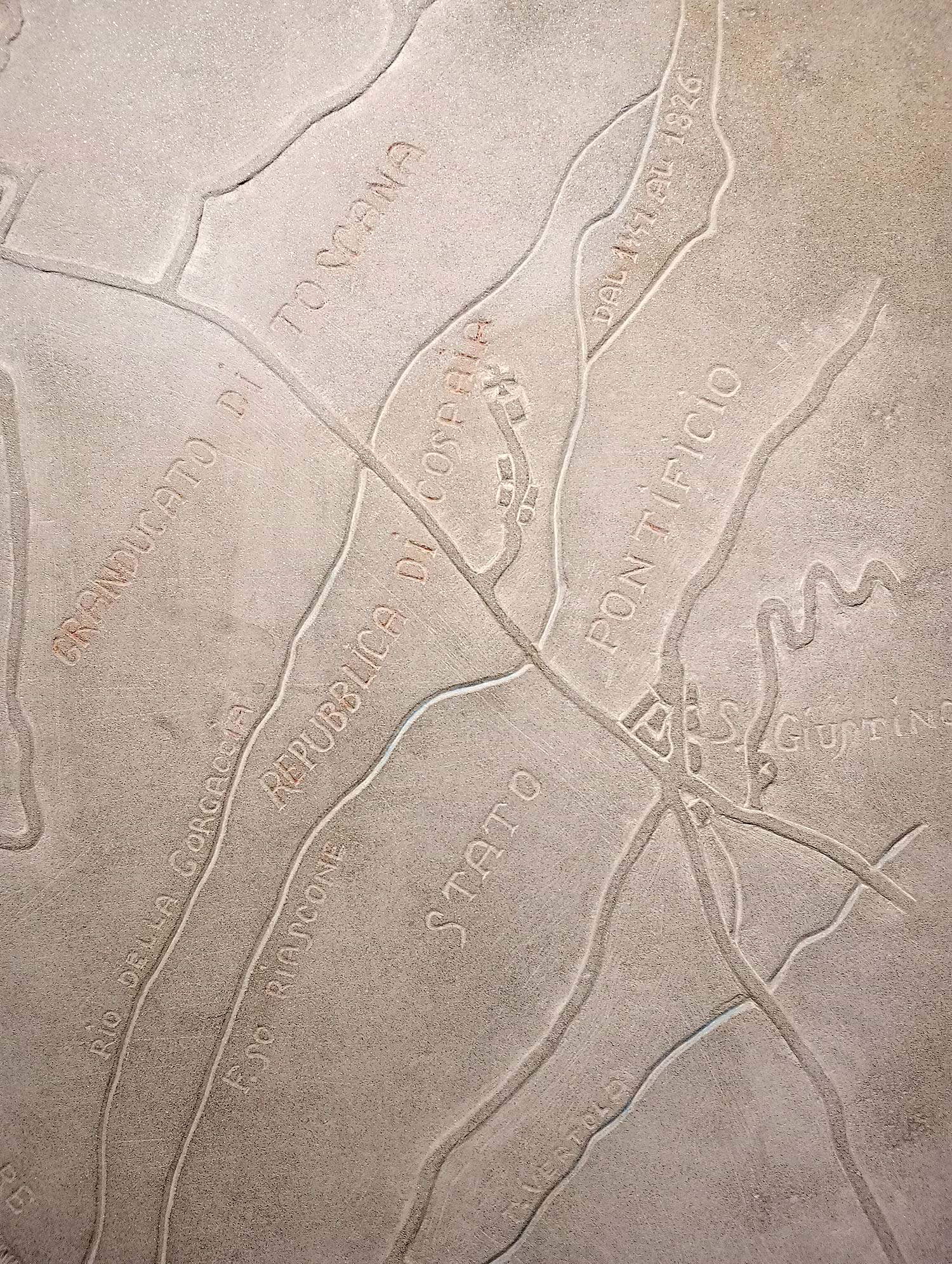

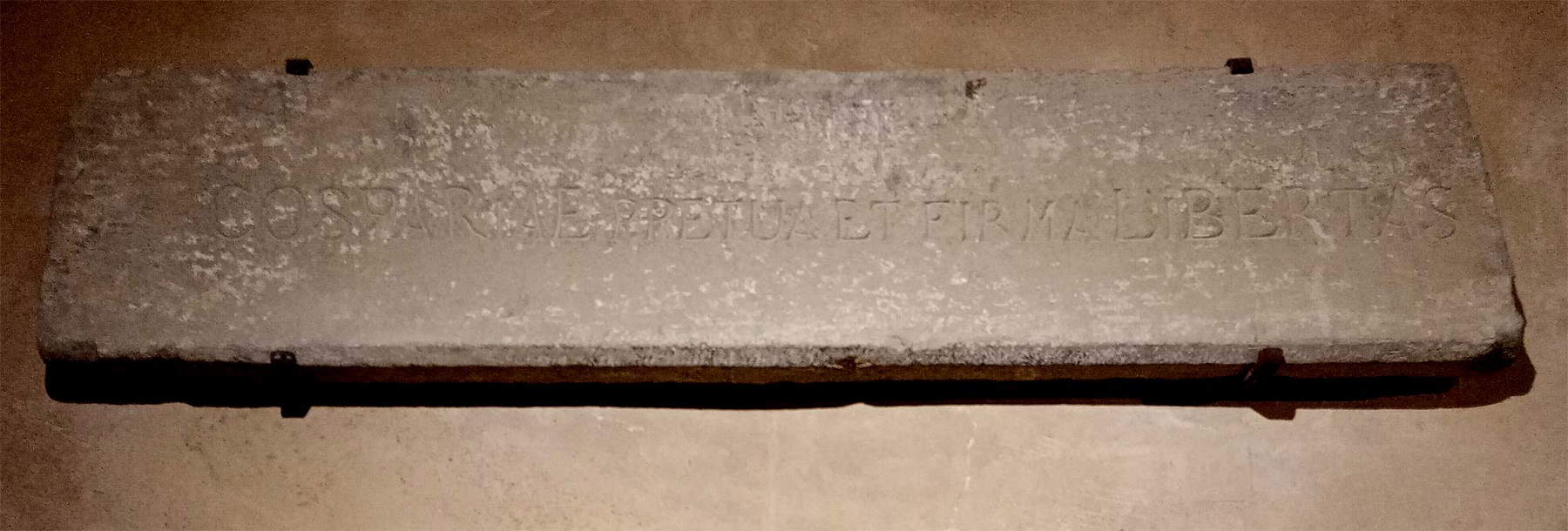

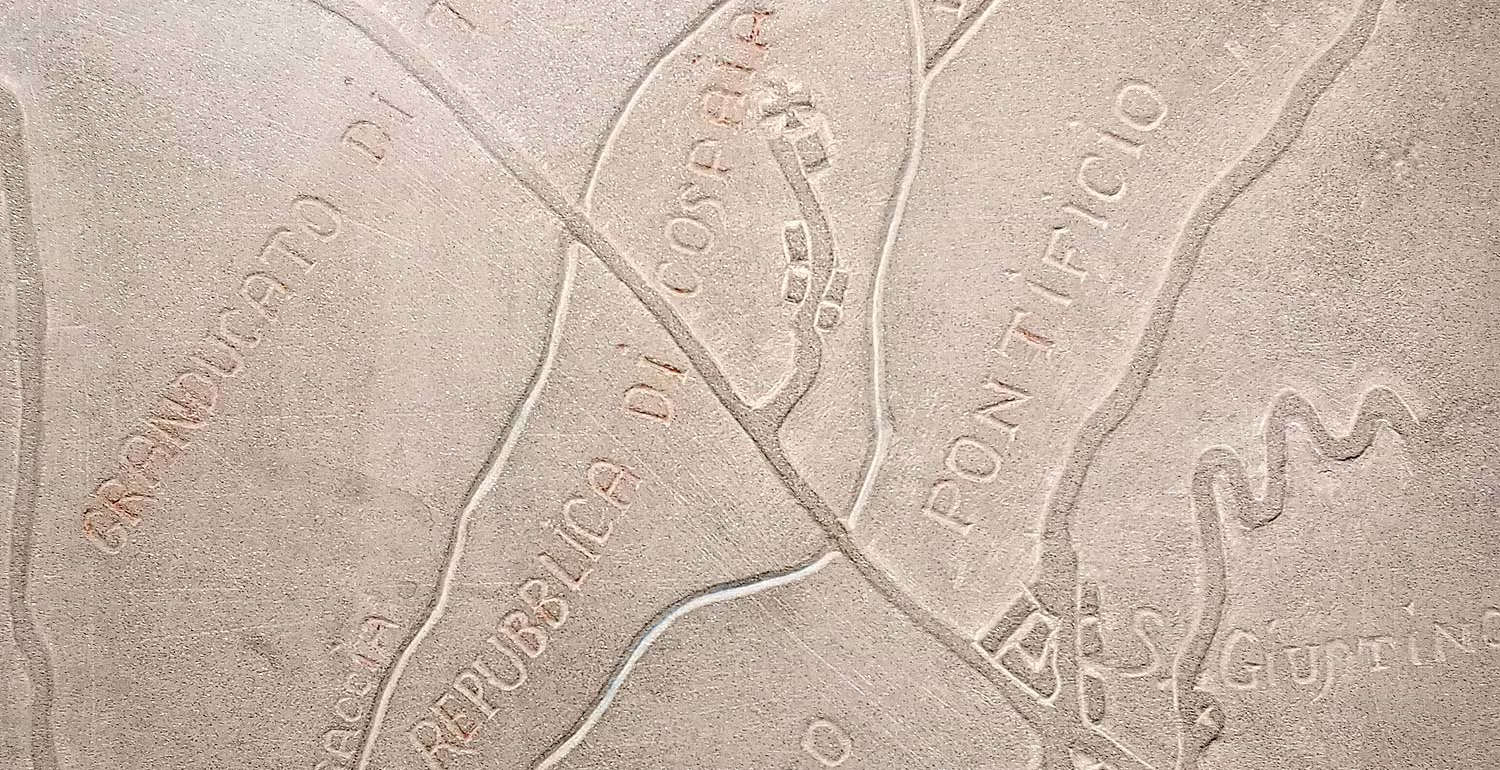

Visiting the Museum of Palazzo Taglieschi in Anghiari, where a marvelous polychrome wood sculpture by Jacopo della Quercia is preserved, you will happen to come across a very curious slab made of pietra serena, a typical material of this area of Tuscany (and which much building material also provided for Florence), on which is traced a map of a state that perhaps not many have heard of: the Republic of Cospaia. Above the slab, one sees instead a bas-relief, also made of pietra serena, which bears the “Formula” of the Republic: “Cospaie Perpetua Et Firma Libertas,” or “Perpetual and Secure Liberty of Cospaia.” These are not two slabs made as a joke, but two artifacts related to a state that not only really existed, but lasted as long as four hundred years. The space it occupied was decidedly small: the Republic of Cospaia was a kind of strip of land two and a half kilometers long and barely five hundred meters wide, corresponding to the village of Cospaia, a locality that still exists today, on the border between Tuscany and Umbria in Valtiberina, exactly halfway between Sansepolcro, in the province of Arezzo, and San Giustino, in the province of Perugia (today it is a fraction of the Umbrian municipality).

The territory of the Republic corresponded to nothing more than the village and the fields surrounding it. A Republic that remained independent from 1441 to 1826. Even today, if you drive along the state road through the Valtiberina, shortly after Sansepolcro you will easily notice a sign pointing in the direction of the “Former Republic of Cospaia.” Complete with chronological details. What is the history of this little state of a few souls? How was it possible to create a state subject in the middle of central Italy, between the territory of the Republic of Florence, on which Sansepolcro depended, and the Papal State , which instead had jurisdiction over present-day Umbria? It all stemmed from an error in the deeds that, in 1441, established the new boundaries of these territories after Pope Eugene IV ceded Sansepolcro, then papal, to Florence. “To the beloved sons, Commune and people of Florence salute”: so opened the deed, written in Latin (here in Italian in historian Angelo Ascani’s translation), by which Eugene IV donated the city of Piero della Francesca to the Florentines. “Since for the manifold and wasteful works that are incumbent on Us and on the Roman Church, and that the Apostolic Chamber has no funds to support them because of the difficulties of the moment, You have lent Us 25 thousand gold florins of seal, received by Us in cash on Your behalf from the most noble son Cosimo Giovanni de’ Medici Florentine domicile; and since We wish to give you according to justice a sure guarantee, the land of Borgo Sansepolcro rightfully belonging to Us and to the said Church, with all its rights, territories and appurtenances We grant and assign to you by apostolic authority and as a pledge of the 25 thousand florins. And as long as you hold that land as a pledge, We by the same authority grant you the mere and mixed empire, the power of the sword, and any territorial jurisdiction equal to that hitherto exercised by the Church; and together with the faculty of electing or deposing therein the podesta, the customary offizials and castellans; to demand and collect the fruits, incomes, revenues and proceeds of the land; and finally to dispose at your full will all that is necessary for the good government, protection and defense of the land.”

The deeds stipulated that the border between Florence and the Church State was to be represented by the Rio stream. However, from the area of the Alpe della Luna two streams descend within a short distance of each other, and at the time both were called “Rio”: today, to avoid misunderstanding, the northern one is called Gorgaccia, and the southern one Riascone. Because of the misunderstanding, therefore, at the time when the commissions charged with drawing the borders, the Florentines officially fixed the border of their state in the northern stream, while the Pontiffs in the southern one: the 330 or so hectares that remained in between were, therefore, to be an independent state, since the knoll on which Cospaia stands is right in the middle of the two rivers. It had become no man’s land. Neither Florence nor the Church claimed the village, at that time inhabited by about three hundred souls. The inhabitants, in essence, overnight found themselves no longer dependent on either the Florentines or the pope. Free. Independent.

How did they take it? This was the question posed by the aforementioned Angelo Ascani. “It is not easy to say,” he explained in his book dedicated to the history of the Republic of Cospaia. “They took advantage of it, however, if nothing else, to evade the taxes and fees of both states, then as always very exorbitant and tyrannical.” And a field that was not subject to taxes automatically became much more profitable. Then, when Florence and the Papal States realized their mistake, it was decided not to change the new territorial arrangement: in the end, it still remained a microscopic buffer state between the two powers, at a time when it was not difficult for two neighboring states to come to a clash. And it was also useful territory for exchanging goods without imposing customs duties. Thus, in 1448, the Republic of Cospaia was officially recognized.

Thus it was that Cospaia was given its own flag (with two fields, one white and one black, divided diagonally: it is still used today during re-enactments), and a form of government that today we would call anarchic, in the sense that in Cospaia there was no government or parliament, nor were there any laws. Everyone decided for himself. There was no police, of course there was no army, there was not even a prison. Only, to settle disputes a council of elders and heads of families was organized, presided over by the village curate, which from 1718 to 1826 met in the Church of the Annunziata, which still exists today, and on whose lintel of the entrance portal we read the motto “Perpetua et firma libertas” (before this time frame the council meetings were instead in the house of the Valenti family, the most influential in the small republic). In case the judicial case was particularly complicated, the inhabitants decided to resort to the nearest courts (those of Sansepolcro and Città di Castello, chosen according to the “sympathies of the parties,” Ascani wrote), and the same in case contracts had to be drawn up (reference was therefore made to the notaries who resided in the surrounding towns), but without an archive being established in Cospaia. The only civil status was, in practice, the parish register, in which births, marriages and deaths were marked. There were no taxes: only a voluntary tax paid by the inhabitants. Payments, however, were in kind, because there were no coins in Cospaia.

For about a century, Cospaia prospered with field work and trade. Then, from 1574, a fact changed the history of the small village: the bishop of Sansepolcro, Alfonso Tornabuoni, received from his nephew, Cardinal Niccolò Tornabuoni (at that time papal nuncio and Medici legate in Paris) a number of goods including the seeds of a then little-known and very valuable plant, tobacco, discovered in America shortly before. Until 1559 it was known mainly in Spain and Portugal, where it was used for ornamental purposes. Introducing tobacco to Italy was another cardinal, Prospero Santacroce, apostolic nuncio to Portugal: it was 1560 when he donated some seeds of the plant to Pope Pius IV. In the same year, interestingly, the French diplomat Jean Nicot (from whom today’s term “nicotine” is derived), ambassador to Portugal, in turn donated tobacco seeds and leaves to Queen Catherine de’ Medici. It was at this time that the plant began to be used as a healing essence. At the time, tobacco (the name comes from the island of Tobago in the Caribbean) was known by several names: Tornabuoni called it “the herb of Santa Croce” because of its properties then considered beneficial, while in Cospaia it was “the herb tornabuona,” named after the man who had brought it to Sensepolcro. And it was in Cospaia that tobacco first began to be extensively cultivated in Italy.

The republic, therefore, became one of Italy’s main centers of tobacco production. A small lake (which still exists today) was also created to allow irrigation of tobacco crops in times of drought. Cospaia’s advantage lay in the fact that its tobacco was not subject to taxation. The circumstance thus attracted numerous smugglers to Cospaia for a long time, moreover confident that in the small state they would suffer no punishment, since there were no laws there. The decline of Cospaia’s tobacco coincided with the period, around the middle of the eighteenth century, when the neighboring Papal State liberalized the cultivation of this plant, thus making it no longer so advantageous for consumers to be supplied with tobacco from the small republic. For the rest of its history, Cospaia’s economy rested on its status as a free port: neighboring states had in fact taken to storing goods in the republic’s territory, since it was not subject to taxation. Then, in 1826, following an agreement between the Grand Duchy of Tuscany and the Papal States who wanted to put an end to the history of the small state, the Republic of Cospaia, by an act of submission signed by fourteen representatives, was divided in two: one part went to the Grand Duchy of Tuscany and one part to the Church State. As it should have been four centuries earlier. The inhabitants, by way of compensation, obtained a papetto, or silver coin (so called by the inhabitants because it depicted the pope of the time, Leo XII) and permission to continue tobacco cultivation, which had never ceased and would continue for a long time, Indeed: after the end of independence it was extended with some intensity to the surrounding territory as well. And even today, Cospaia is known for the fine tobacco that is still grown here. The story of that ancient republic that was born by mistake and remained romantically free for four hundred years continues in the product that most characterized its history and made it most famous.

|

| The Republic of Cospaia: history of a state born by mistake in Valtiberina |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.