Every year, on June 16, the palaces that line Pisa ’s lungarni are lit up with tens of thousands of lights: this is the Luminara di San Ranieri, one of the most fascinating and long-lived events held in the city of the Leaning Tower, an annual event that illuminates the city, awakens the spirit of belonging of its inhabitants and offers visitors a spectacle that has no other equal. The Luminara is held on the night of the eve of the feast of St. Rainier, the city’s patron saint: the center of the celebration is the streets that run along theArno River, where the facades and windows of historic buildings are adorned with glasses, in the past made of glass and now made of plastic for safety reasons, containing candles, which, when lit, create a magical effect, reflecting on the waters of the Arno. These are the so-called “lampanini,” wax candles that are lit on the “biancherie,” special wooden frames, painted white, built to accommodate the lights. All artificial lights are turned off, only the lights of the lampanini remain lit, and the architectural lines of the buildings, made to stand out by the biancherie, emerge in a play of chiaroscuro, which enhances the beauty of the historic facades and transforms the city into a kind of work of art that is seen only once a year.

The tradition of the Luminara has its roots in 1688, when the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Cosimo III de’ Medici, ordered the transfer of the relics of St. Ranieri degli Scaccieri, who died in 1161, to the new urn, commissioned from the celebrated sculptor Giovanni Battista Foggini (Florence, 1652 - 1725), the greatest sculptor of Grand Ducal Tuscany in the late 17th century. On the occasion of the translation of the urn, a great feast was called, which would be repeated every three years from then on, as also attested by the great man of letters Vittorio Alfieri, who in his Vita scritta da esso, the autobiography composed in 1790 and later revived in 1803, states that in 1785 he first witnessed the “amusement of the Giuoco del Ponte, a beautiful spectacle, which brings together something of the ancient and heroic,” and then to “another beautiful feast of another kind, the Luminara of the whole said city, as is customary every three years for the feast of San Ranieri.” Initially it was called “Illumination”: only in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries is the term “Luminara” attested, which would later be used to this day.

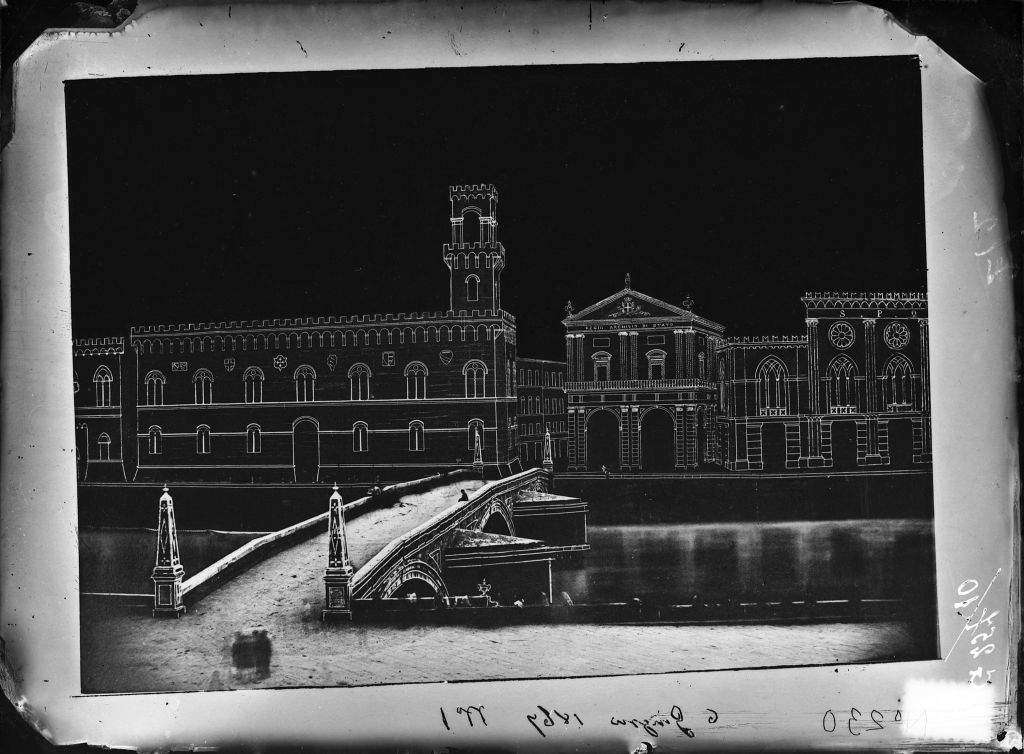

The history of the Luminara has not always been linear: it was in fact abolished in 1867, then reinstated in 1937 (the year in which the tradition of the Gioco del Ponte was also resumed), then again suspended during World War II and reactivated in 1952. In 1966, the year of the devastating flooding of the Arno that caused extensive damage in Florence and all of Tuscany, Pisa also found itself scourged: in fact, the Solferino Bridge collapsed and large portions of the lungarni were damaged, and the Luminara was again suspended. Only in 1969 was it re-established: since then, every year, the banks of the Arno have shone with thousands of little lights (an estimated one hundred thousand lampanini are displayed on the whitecaps), carefully and precisely arranged to outline the outlines of the palaces and churches overlooking the river.

But the Luminara is not just a visual experience. It is a time of celebration and sharing, when Pisans and tourists alike take to the streets to participate in one of the community’s most heartfelt events. Along the river, one can encounter musicians, street performers and markets, which add liveliness to the event. The evening finally culminates with a fireworks display that, at around 11:30 p.m., lights up the sky of Pisa, also reflecting on the Arno and amplifying the magic of the night. The fireworks, with their bright colors and spectacular shapes, fired from the Citadel (but for some years also from some platforms that are specially made to arrive on the Arno) enchant adults and children alike, and conclude the Luminara in a blaze of light and sound.

Participating in the Luminara di San Ranieri is an experience that goes beyond the simple event: it is a festival that has been held for four hundred years, and is therefore a journey through time and tradition, a way to immerse oneself in the soul of Pisa and discover its history and culture. The custom of illuminating the palaces, however, dates back long before 1688: there is often mention of a document dating as far back as 1337, the year in which there is news of an apothecary, a certain Guido di Bonagiunta, to whom the council of the Elders of Pisa acknowledged a sum spent to purchase candles and candle lights for the eve of Blessed Ranieri (he would, moreover, only become patron saint of the city and the Diocese of Pisa in 1632). However, we do not know if the candles were used for lighting the buildings: more likely, it was simply the purchase of candles to accompany a procession, as was the custom at the time. Again, there is an account dating from 1662, on the occasion of the visit to the city of Margaret Louise of Orleans, who was passing through Pisa on her way to Florence where, on June 20 of that year, she was to marry Grand Duke Cosimo III: this is a passage from the Memoirs of the Festivities Made in Florence for the Royal Wedding of the Most Serene Spouses Cosimo Prince of Tuscany and Margaret Louise Princess of Orleans, written by the diplomat Alessandro Segni (1633 - 1697). The Luminara’s description for the bride’s passage is to the date of June 14: “Entrò S.A. into Pisa through the Porta a Mare greeted with the firing of artillery from the forts, which defend on that side the opening of the river: precisely at a time when the air had become very dark because of the intervening night; but the copious quantity and the orderly arrangement of the facades and lights, so that the windows of all the houses and palaces were adorned with such great light, that they did not overcome the darkness of the night, but could contend with the day with serenity. The majestic procession came through the city along the banks of the river, whose waters with multiplied splendor reflecting the surrounding lights rendered to the spectators’ view the images of the magnificent Palagi and the great buildings surrounding it.”

Initially, the lampanini lights did not have to follow any particular arrangements. The custom of shaping the illuminations probably dates back to the 18th century and is certainly documented in the 19th century. Dating back to 1875 is a description, written by a local nobleman, Cosimo Agostini, who speaks of a “machine representing a Chinese perspective, with niches and needles, which contained no less than fourteen thousand lamps,” installed on the sea bridge (no longer extant today: it was located near the Citadel), while near the Fortress there was “a machine representing a grandiose and noble entrance with three large doors, pillars and pediment of composite order of a length of one hundred and twenty fathoms, and thirty-two high in whose upper middle point one could see the Pisan Arms and in whose design fifteen thousand lumens burned.” The biancherie have therefore been used for more than two centuries as installations to create unique and special designs.

The Luminara of San Ranieri has thus, for centuries, been a moment of celebration and wonder, in which the light of candles also becomes a symbol of hope and renewal. It represents one of the most intensely experienced moments in Pisa, an unbreakable link between past and present, sacred and profane. It is a celebration that unites, excites and pays homage to the beauty of Pisa. Every year, the Luminara renews its magic, continuing to enchant anyone who has the pleasure of witnessing it on this late spring night. Sometimes, however, it can happen that special Luminaras are organized to celebrate other events, unrelated to the cult of Saint Rainier. It happened on December 31, 1999, when a Luminara was organized to celebrate the beginning of the new millennium.

To walk along the Lungarni during the Luminara is to immerse oneself in an atmosphere suspended between dream and reality. The sound of the flowing river creates a perfect background for this light show. Lanterns, positioned with geometric precision, draw contours and shapes that enhance the architectural richness of the city. Bridges become enchanted settings where tradition meets the contemporary in an embrace of light.

The organization of the Luminara requires intense preparation and the tireless work of many volunteers. Initially, the lighting of the lights, in times when there was noelectric lighting, was functional to enliven the passage of the processions and processions that were organized in honor of the city’s patron saint. Today, this need has been lost and the tradition of profiling the design of the buildings and churches that line the riverbanks has remained. The lighting of the candles begins around three o’clock in the afternoon: every detail is carefully attended to, from the decorations to the security arrangements, to ensure that everything runs as smoothly as possible. The people of Pisa work passionately to keep this tradition alive, aware of the cultural and spiritual value it represents. Then, around sunset time, all artificial lighting, both public and private, is turned off to let Pisa live only by the light of the lampanini.

The feast of St. Rainier is also a time of deep spirituality for the people of Pisa. The saint, remembered for his life of charity and devotion, is celebrated on June 17 with a solemn mass held in the cathedral. And also on the saint’s day, the Palio di San Ranieri is organized, a unique historical regatta in honor of the city’s patron saint, in which the four historic districts of central Pisa (Santa Maria, San Francesco, San Martino and Sant’Antonio, characterized by the colors celeste, yellow, red and green, respectively) compete on the Arno with their rowing boats to win the palio mounted on top of a flagpole that is specially installed in the middle of the river.

In addition to its religious and spectacular aspect, the Luminara di San Ranieri also has significant economic importance for the city. Indeed, it attracts several tourists, who come to admire the beauty of the festival and to discover the wonders of Pisa. Hotels, restaurants and stores prepare to welcome visitors, offering the best of the local food and wine and craft traditions.

The Luminara di San Ranieri is thus an example of how traditions can be preserved and enhanced over time. It is an event that involves all generations, from the youngest to the oldest, creating an intergenerational bond that strengthens the sense of belonging and community. Each year, the city renews itself in this celebration, proving that the light of tradition can continue to shine in the heart of Pisa. Not just a celebration, but a journey into the soul of Pisa. It is an opportunity to rediscover the beauty of the city under different lights than usual, to experience moments of sharing, to be enchanted by the magic of a night lit by thousands of candles.

|

| The Luminara of San Ranieri in Pisa: origins and history of the festival of lights |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.