It is known as the “queen of the Venetian villas.” and indeed, Villa Pisani in Stra is a significant, elegant, majestic presence; it is impossible not to notice it as one travels along Veneto Regional Road 11, or the long road that leads from the center of Venice, from Piazzale Roma, to the gates of Padua, skirting the Brenta Canal, along which stand several of the villas that in ancient times the Venetian patriciate had erected in these pleasant countryside as vacation spots away from the city chaos of Venice. The largest is Villa Pisani, whose origins date back to the 18th century, when the Pisani di Santo Stefano, one of the richest families of the Venetian nobility Venetian, reached their apogee, even managing to express a doge, Alvise Pisani, who was first Venetian ambassador to Louis XIV’s France, after which he ascended to the doge’s throne in 1735, when Villa Pisani was under construction.

Construction of the complex began in 1721, when the Pisani family entrusted the task to architect Gerolamo Frigimelica (Padua, 1653 - Modena, 1732), also the author of the sumptuous Palazzo Pisani in the sestiere of San Marco in Venice, and then to his colleague Francesco Maria Preti (Castelfranco Veneto, 1701 - 1774), who succeeded Frigimelica after his death in 1732. It took a few years to see the work completed, which ended in 1756. The villa, however, remained with the Pisani for a short time: in the late 18th century, the time of the decline of the Serenissima, the family also suffered heavy setbacks, and the villa had to be sold off to meet the debts the Pisani had accumulated. Villa Pisani thus became the property of Napoleon Bonaparte, who in turn gave it to his stepson Eugene de Beauharnais. After the Restoration, it became the imperial villa of the Habsburgs, who spent long holiday stays here. Then, following the Unification of Italy, the villa became part of the property of the Savoy crown, and in 1884, after a period of neglect, it was turned into a museum.

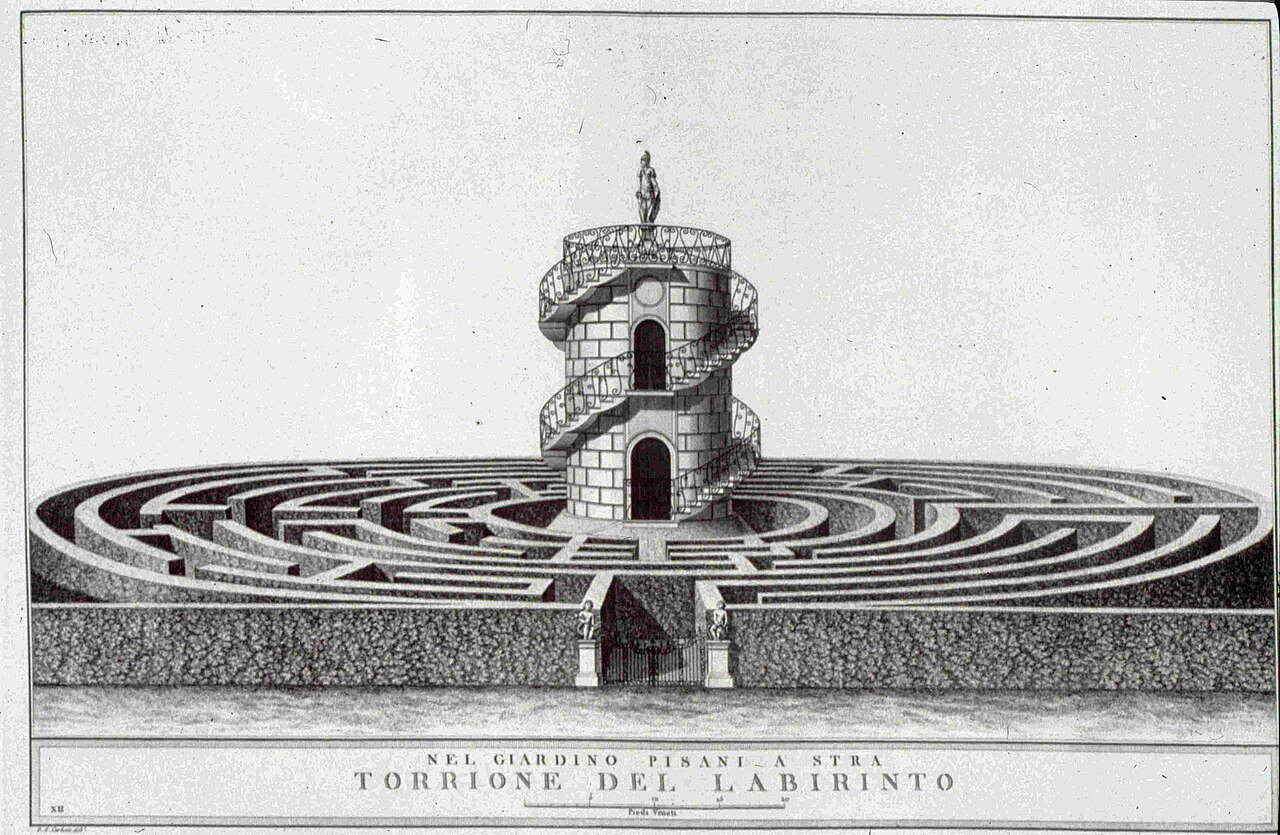

Villa Pisani is an imposing structure that behind its sober neoclassical façade conceals dozens of rooms (there are 168 in all, although those that can be visited number around 30), including the spectacular ballroom where Giambattista Tiepolo frescoed theApotheosis of the Pisani Family, one of the greatest masterpieces of the eighteenth century in the world. Attached to the villa is then a splendid 14-hectare park with stables, the 18th-century Coffee House, English grove, tropical greenhouses and one of the most famous labyrinths inItaly, the Labyrinth of Villa Pisani precisely, which also became famous because it is the protagonist of one of the best-known scenes in the novel Il Fuoco by Gabriele D’Annunzio, who visited the villa after its transformation into a museum, dedicating unforgettable pages to it. In the novel, the young protagonist, the poet Stelio Effrena, travels through the labyrinth together with his lover, the Foscarina, in a subtle game of love among the maze’s meandering paths: “A gate of rusty iron closed it, between two pillars bearing two Lovers riding dolphins of stone. There was no glimpse beyond the gate except the beginning of a medium and a kind of tangled and hard forest, a mysterious and thick appearance. From the center of the tangle rose a tower, and at the top of the tower the statue of a warrior seemed to stand at the lookouts. ’Have you ever entered a labyrinth?” asked Stelio to his friend. ’Never,’ she replied. They lingered to admire that fallacious game composed by an ingenious gardener for the delight of ladies and cicisbei in the time of calcagnini and guardinfanti. But neglect and age had inselvated it, saddened it; had stripped it of all semblance of gracefulness and equality; had changed it into a closed patch between brown and yellowish, full of inextricable ambiguities, where the slanting rays of sunset reddened it so that the tufts here and there there looked like pyres burning without smoke. ’It is open,’ said Stelio, feeling the gate give way in leaning against it. ’See?’ He pushed the rusty iron that screeched on the shaky hinges; then he gave a step crossing the boundary."

The labyrinth is also due to the design of Gerolamo Frigimelica, and probably the idea of enriching the park of the villa with a maze is due precisely to the future doge Alvise Pisani, who during his stay in France perhaps had the opportunity to appreciate the labyrinth of Versailles, later removed in 1778 at the behest of King Louis XVI, who had it replaced with an English garden. It had been designed, as D’Annunzio writes, for the enjoyment of guests: the Vate thus imagined the ladies invited to the villa wandering around the meandering maze, dressed according to the fashion of the time, that is, with the “calcagnini,” typical eighteenth-century Venetian shoes provided with a high wedge (they had been invented to avoid the ’high water), and the “guardinfanti,” the structure composed of metal or wicker hoops that served to inflate the skirts by making the garment take on that particular bell shape seen in portraits of the time. Apparently, one of the most popular games played by the labyrinth’s frequenters involved a lady masquerading on the turret and revealing her identity only to the gentleman who, in a race with others, managed to reach her in the shortest possible time.

It is one of the largest labyrinths in Europe, as well as one of the most intricate and difficult. The difficulty is due not only to the vastness of its proportions, but also to the fact that it is a labyrinth that has only one path leading to the center, and each junction or fork never allows you to find an alternative route, but always leads to a dead end, with the result that if you come to a wall you have to perforce retrace your steps trying to remember where you found the fork and choose another path. For this reason it can also take a long time before one is able to find the road that leads to the destination. It is even said that Napoleon, after acquiring the villa, wanted to try his hand at the Labyrinth of Villa Pisani in 1807, but he failed to solve it, and again tradition has it that in 1934, when Villa Pisani was the scene of a summit between Hitler and Mussolini, the two dictators preferred not to measure themselves against the labyrinth because, mindful of the anecdote about Napoleon, they would have preferred to avoid embarrassment. The labyrinth has a circular floor plan and consists of nine concentric circles that lead from the entrance (the only entrance) to the center where a stone turret towers, with double-row centered openings, the top of which can be reached by double a spiral staircase, equipped with a wrought-iron balustrade, that wraps around the structure. Above the turret, the final goal: the statue of Minerva, goddess of wisdom, an indispensable virtue for keeping calm and reaching the center of the labyrinth. The corridors are separated by boxwood hedges(buxus sempervirens) that allow one to always see the center: boxwood is a typical plant for labyrinths, since it is very hardy, requires little maintenance, can be ’tamed’ into many forms, and is an evergreen. However, it is not the original essence of the maze: in ancient times it was in fact composed of hornbeam hedges, a plant that was then gradually replaced until by the early twentieth century the labyrinth was already entirely made of boxwood, which was evidently chosen because of its characteristics, first and foremost the fact that it can maintain the coloring of its leaves in all seasons, while the hornbeam is a deciduous plant (which, however, does not lose its leaves: they remain attached to the branches but yellow).

The labyrinth of Villa Pisani has always maintained the same structure, since eighteenth-century prints are known to show the maze as it is now. Even one of the greatest artists of the eighteenth century, Francesco Guardi (Venice, 1712 - 1793) passed through here: in fact, one of his drawings sketching a corridor of the Villa Pisani Labyrinth is preserved. And of course, one cannot count the novels, even contemporary ones, that have scenes set here. The only change was made in 1809, when, at the behest of Eugene de Beauharnais, a slight widening of the path was decided: the circle of the labyrinth, which was accessed, as the ancient prints attest, by an entrance placed along a wall, was in fact added some corridors on four sides to inscribe the structure in a trapezium designed by the engineer Mezzani, “Royal Architect and Inspector of the Royal Palaces of Venice and Stra” as it is indicated in the Napoleonic documents. But the circle part has always remained unchanged. And it has also been widely imitated, all over the world: several labyrinths in fact recall the structure of the one at Villa Pisani (the closest geographically is the one at Villa Gaggia in Belluno, which also has a very similar turret in the center).

Restored in the 1970s after a period of decay, the labyrinth is once again offered to visitors to Villa Pisani, who, at certain times of the year, can put on the clothes of 18th-century nobles and try to solve the pattern: a labyrinth that is at once amusing and disturbing (as emerges from the pages of D’Annunzio, where the Foscarina feels some anxiety as she navigates its meanders), because it is designed to pass the time of the villa’s guests but also to disorientate, because when you get to the turret you can enjoy beautiful views and serene moments of tranquility, but then once you get down you have to retrace the whole way back. A labyrinth of ambiguous charm that never ceases to seduce all those who try to walk through it.

|

| The Labyrinth of Villa Pisani in Stra, suggestions of D'Annunzio and an intricate pathway |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.