The labyrinth mosaic of Cremona: a testimony from the ancient Roman city

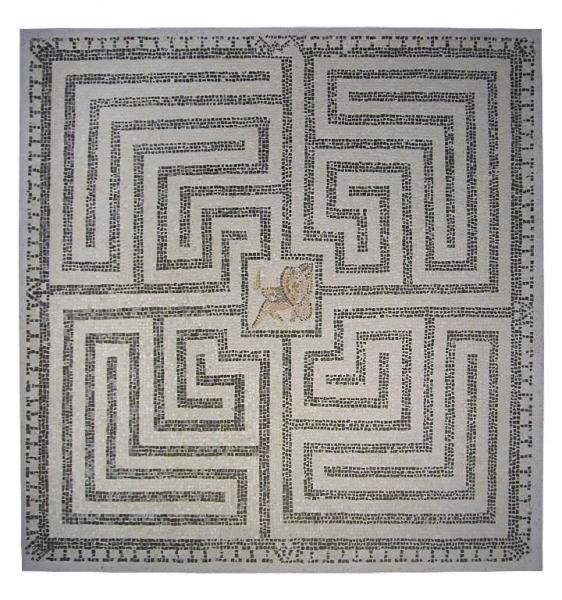

In ancient Rome, upon entering a domus of some noble family, it would not have been uncommon to come across a floor covered with a mosaic in the shape of a labyrinth. Several have been found: as we wrote on these pages, the oldest known labyrinth mosaic is that of the House of the Labyrinth in Pompeii, which probably dates from the first century B.C. But many other mosaics with labyrinth motifs are known, which follow recurring patterns and, in the center, are decorated with an illustrated scene, often related to the story of the labyrinth itself. One of the best-preserved mosaics is the mosaic from the domus in Via Cadolini preserved at the “San Lorenzo” Archaeological Museum in Cremona.

Roman labyrinths, wrote Jeff Saward, one of the world’s most recognized experts on labyrinths and author of the labyrinth that can be walked in the Chianti Sculpture Park, “represent the first real attempt to create different forms and the first major modifications to a symbol that had been circulating for some two thousand years.” Indeed, the structures of Roman labyrinths, though variable in size and breadth, are recurring: “basically,” Saward further explains, “most of the sixty or so documented or preserved Roman labyrinth mosaics can be classified into the meander, serpentine and spiral types, with only a few complex structures falling outside this simple system.” The Cremona maze is a typical meander maze.

Not much remains of Roman Cremona today, and the mosaic floor preserved at the Archaeological Museum is certainly one of the best known and most important testimonies to the ancient city. It was unearthed in the 1950s in Via Giovanni Cadolini (in the historic center of Cremona) during an excavation for the expansion of the headquarters of the Stipel telephone company (Società telefonica interregionale piemontese e lombarda), later incorporated into SIP. Some remains had already been identified between 1926 and 1927, but in 1952, with the demolition of the church of San Giovanni Nuovo, it was possible to bring to light the entire complex of the domus, dating from the first century B.C. and destroyed, probably, in 69 A.D, in the course of the Roman civil war that saw the clash between four emperors acclaimed by their respective legions (69 is in fact known as “the year of the four emperors”), which ended with Vespasian’s victory. On October 25, the city of Cremona, controlled by Vitellius’ supporters, was besieged by Mark Antony Prime, Vespasian’s general, who managed to enter the city, which was eventually sacked and set on fire. The labyrinth domus was destroyed during these events.

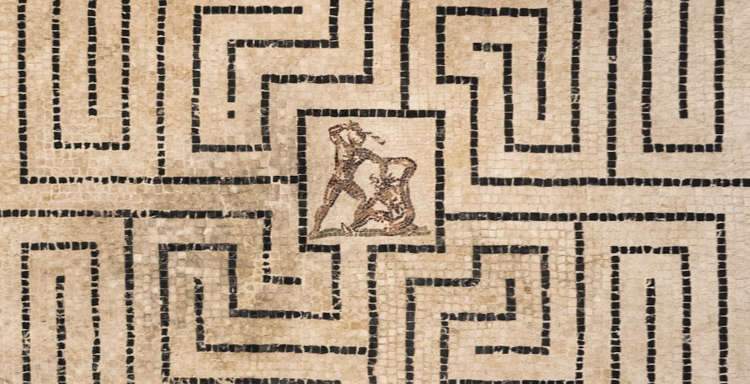

The domus was located in an area of ancient Cremona where other evidence of decorated floors has been found, reasoning that it must have been the most valuable residential area of the city. The labyrinth decorated anantechamber that led into a large living room, the main room of the domus, which was decorated with colored marbles from various areas of the Mediterranean (further evidence of the status of the master of the house). The meanders and walls of the labyrinth are made of black and white two-colored tiles, while in the center, as is often the case, is a depiction of the scene of Theseus slaying the Minotaur, executed in polychrome tiles, in a much simpler and less elaborate style than the same scene decorating the labyrinth in the house of the same name in Pompeii. On the sides of the labyrinth one will easily see a crenellated decoration while on the corners appear what appear to be four towers and, in the center, along the lower edge, the entrance to the labyrinth: the mosaic was in fact intended to replicate a real building, a sort of castle with the winding path inside that led toward the center where the minotaur was located. Curiously enough, in an excavation in ancient Bedriacum, a village not far from Cremona, a similar floor was found, moreover always in the same period: the mosaic of the Bedriacum labyrinth, found in 1959 in a domus (obviously renamed “domus of the labyrinth”), in a state of preservation that was far from optimal, was restored and placed in the Civic Archaeological Museum of Piadena, where it is still preserved today.

We are not sure why the labyrinth motif was so common in the homes of Roman patricians: one possible explanation is related to the Theseus myth itself. The Greek hero was regarded by the Athenians as a father of the fatherland, and in the Roman sphere his iconographic presence is linked to the theme of the founding of cities: it is likely that those who commissioned a mosaic with a labyrinth and a scene depicting the slaying of the Minotaur saw themselves as a bearer of civilization, perhaps because of some feat he had accomplished. It is possible to imagine something like this for Cremona as well, although it is not known who the owner of the domus on Via Cadolini was.

After being removed from its original location, the mosaic floor of the domus in Via Cadolini was displayed in 1963 at the “Ala Ponzone” Civic Museum in Cremona, reassembled by restorers Felice and Edoardo Bernasconi. Finally, in the early 2000s, the mosaic was restored again and then transferred, in 2009, to the halls of the “San Lorenzo” Archaeological Museum. Where you can still admire this mosaic, which is not only one of the best-preserved Roman labyrinths, but also one of the best-known and most relevant mosaic testimonies in the Po Valley.

|

| The labyrinth mosaic of Cremona: a testimony from the ancient Roman city |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.