It is a fairly common occurrence to find Roman mosaics depicting labyrinths. They have been discovered in several cities of the Roman Empire, are made with great attention to detail and can vary in complexity, and were usually placed in the most important spaces of domus, the typical houses of patrician families, with rooms arranged around a central courtyard. The labyrinth motif, explains scholar Gian Luca Grassigli, “is thought to have entered the repertoire of Roman artistic production through textiles, particularly during the Hellenistic age,” and constituting a recurring ornamental element of carpets, the motif “was then passed on to permanently decorate floors.”

The oldest known Roman labyrinth mosaic is the one that gives its name to one of Pompeii’s most famous domus : the House of the Labyrinth. It was built in the 2nd century BC, and is a house with a double atrium (probably as the result of the union of two houses: the main atrium is in Corinthian style, the secondary atrium in Tuscanic style) and equipped with a peristyle (the peristyle was a courtyard with columns), damaged in 89 BC. during the siege of Pompeii by Sulla’s legions, after which it became the property of one of the city’s most powerful families, the Sextilii, who undertook major renovations, during which a small thermal area was also added, a kind of ancient “spa,” to give an idea. Then, probably after the earthquake of 62 AD, the wall decorations were made, traces of which can still be seen today. Instead, the first excavation of the house dates back to 1831, which was continued between 1834 and 1835.

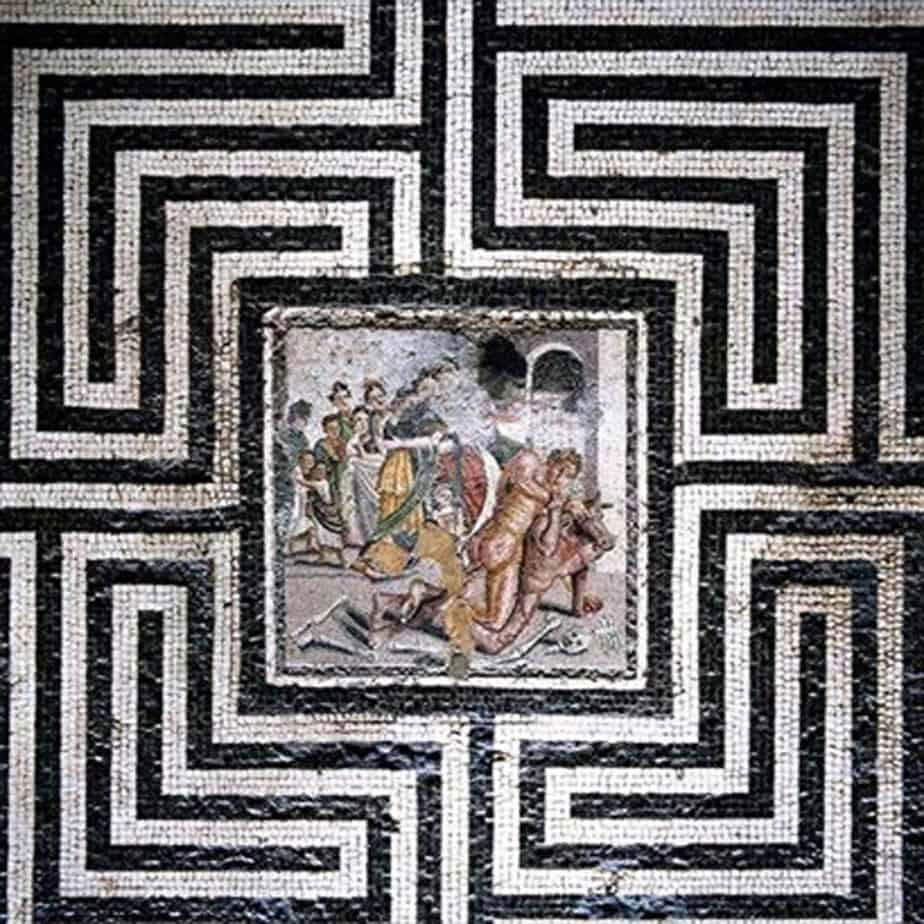

The floor mosaic with the labyrinth decorates the master cubiculum , or bedroom, which is located in the noblest room of the house, one that is built around an oecus, or reception room, surrounded by two pairs of bedrooms. The labyrinth cubiculum has sumptuous frescoed walls, dating in all likelihood, as mentioned, to work done after 62 CE.

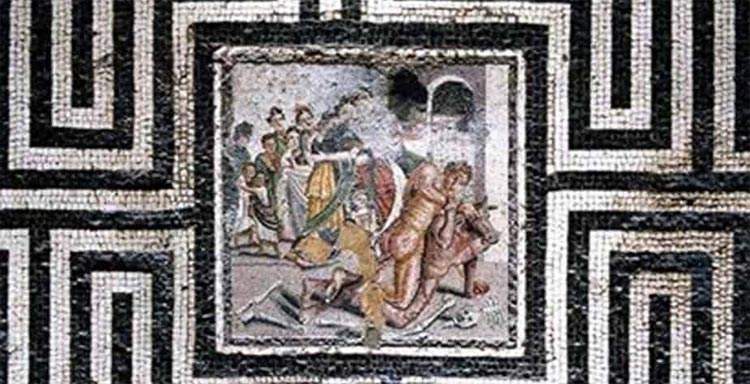

The mosaic of the House of the Labyrinth presents a serpentine maze, divided into four sectors, as is the case in virtually all Roman labyrinths, and with a depiction of a scene(emblem) in the center, in this case a typical scene and perfectly in keeping with its motif, namely, Theseus ’ struggle with the Minotaur, the mythological creature half man and half bull: the labyrinth had been designed by the formidable architect Daedalus precisely to imprison the dangerous creature, and the Athenian Theseus was the hero who killed the beast (which, every year, demanded, to satisfy its hunger, the sacrifice of seven girls and seven boys that Athens was required to send to Crete as it was defeated by the Cretan king Minos). The scene, also executed in mosaic and today unfortunately rather ragged, shows us the final moment of the confrontation, the moment when the hero gets the better of the hideous creature, and is about to win it observed by a group of people, among them probably Ariadne, princess of Crete who had fallen in love with Theseus and had helped him find his way out of the labyrinth thanks to her celebrated thread. The building in the background is likely the Palace of Knossos.

The true meaning of Roman labyrinths, and of this one in particular, remains a matter of debate among scholars. There is no definitive explanation, but there are several theories about the intention behind these motifs. One may think that the labyrinths have symbolic meanings and allude to life paths or spiritual experiences. But one can also safely assume that the labyrinth is merely decorative in nature, or at most serves solely to contextualize the central scene, thus building a plausible setting for the episode of the confrontation between Theseus and the Minotaur.

The central scene of the

The central scene of the The

The

And there may also be symbolic reasons behind the choice to depict the struggle between the two mythological characters in theemblem . “Since the owner and chronology of the House of the Labyrinth are known with good verisimilitude,” Grassigli goes on to explain, “it was possible to search for more specific motives, which would justify the whole decoration with even greater meaning. On the one hand, it was felt that it was possible to interpret the minotauromachy as an allusion to the victory over the Italics, of which the Minotaur would be a mythical projection, and thus as a direct reference to the Sillan conquest and the founding of the colony, events directly related to the chronology of the domus.” Archaeologist Fabrizio Pesando, looking for a closer connection between the theme of the floor decoration and the subjects of the room’s paintings evoking a naval victory, proposed that “the entire room celebrated the defeat of the pirates by Pompey, an event that, beyond official propaganda, must have been particularly felt in a port and commercial city like Pompeii. The connection between the mosaic and the celebrated event would then be to be recognized in the Cretan setting of the Minotaur affair, that is, the island believed to be the main seat of the pirates who made the trade routes dangerous.” These are two very different interpretative proposals, which, moreover, also presuppose two distinct chronologies, and which can only leave the question open. The figure of Theseus, considered by the Athenians to be the father of the homeland, was connected in Roman iconology to the theme of the founding of cities, and in this sense perhaps it could be recalled, especially if one imagines that the work may have been created after the final conquest of the city by the Romans.

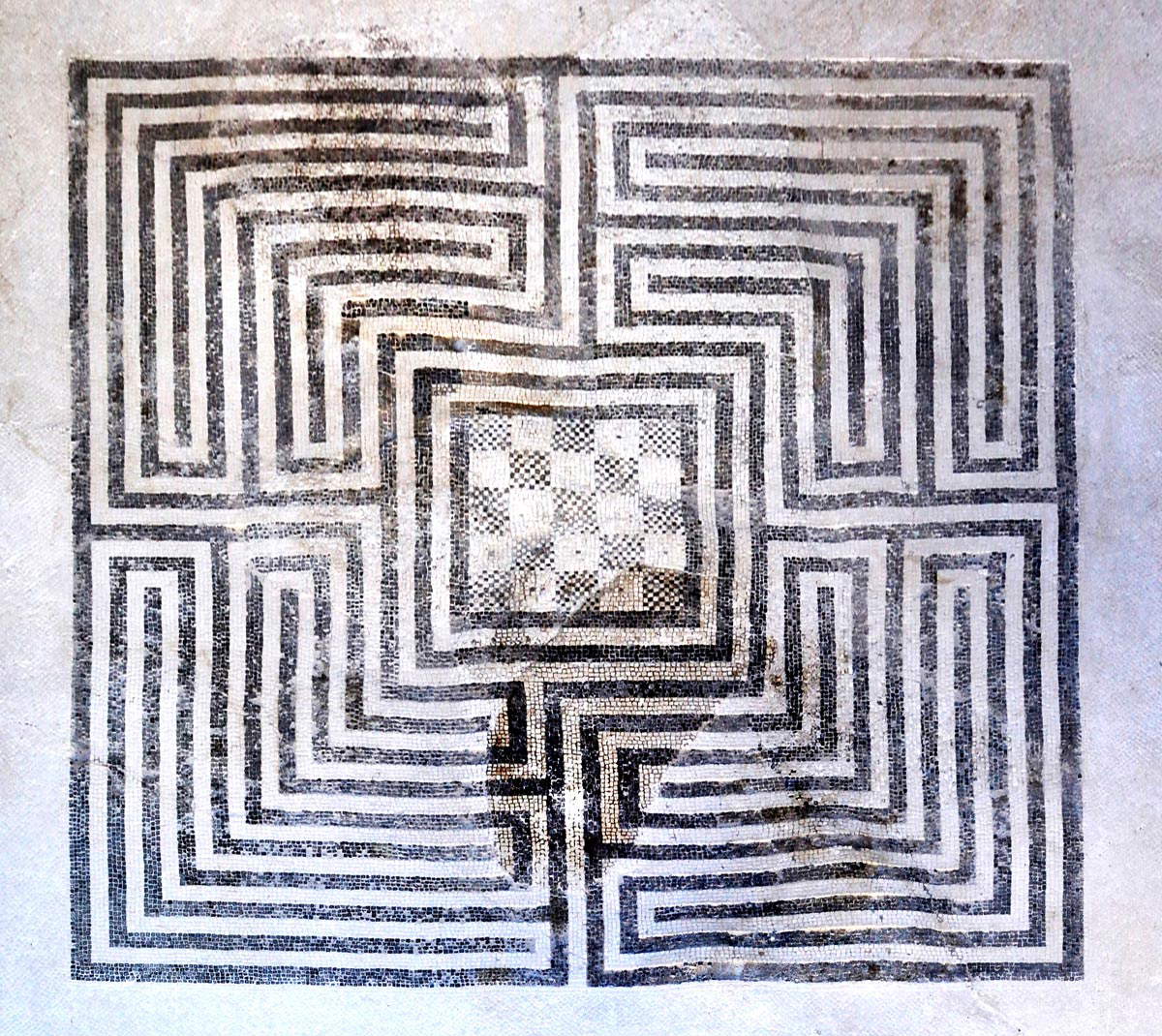

The one in the House of the Labyrinth is not the only mosaic depicting a maze to be found in Pompeii. Three others have been found: the best known is certainly the labyrinth in the House of Geometric Mosaics, which has an identical plan to the one in the House of the Labyrinth, but has a checkerboard pattern in the center. And there are also labyrinths not necessarily made of mosaic. On one wall of Marcus Lucretius’ house, for example, was a graffito (today only drawings of it remain, made in the nineteenth century) depicting a labyrinth built with the classical plan, accompanied by the inscription “labyrinthus hic habitat Minotaurus,” meaning “labyrinth, here dwells the Minotaur.” We have no idea of the meaning of this graffito: perhaps a mockery of the landlord, identified as a “minotaur” (given also the graffito’s emphasis on the word “Minotaurus”), thus someone to stay away from. And finally, there is another labyrinth also-in the Labyrinth House. It is the one of hedges planted in the courtyard of the domus in the 1950s: a maze of boxwood divided into four sectors, thus following the pattern of Roman labyrinths, with a palm tree in the center. A tribute both to the labyrinth that gives the house its name and to the art of gardening, at which the Romans excelled.

|

| The House of the Labyrinth in Pompeii: the first known labyrinth mosaic |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.