The figure of Medusa in art: 10 works in 10 Italian museums

The mythological figure of the Gorgon has ancient roots. Its term comes from the ancient Greek gorgós, meaning terrible or even horrible. According to Hesiod, in his Theogony, the three Gorgons are daughters of Phorcus and Ceto. Depicted with terrifying appearance, they have golden wings, boar’s tusks, snakes instead of hair, and a petrifying gaze. They embody depravity in their three manifold forms: Medusa is the only mortal and symbolizes intellectual perversion, Steno moral perversion, and Euryale represents sexual perversion. Ancient writers locate the sojourn of the three creatures in the far west, near the realm of the dead.

Gianni Versace, a celebrated Italian fashion designer of Calabrian descent, drew inspiration from the Gorgon figure reproduced in Greco-Roman mosaics found in Calabria to create one of the most recognizable and iconic brands in the fashion world. Versace used the creature’s image as the symbol of his brand with the stylized face of Medusa. Indeed, his choice is not random: the image of the Gorgon symbolizes power, beauty and mystery; elements that Versace has been able to embody in his aesthetic and vision of fashion. Versace’s logo with the face of Medusa has become an icon in the fashion world and a symbol of luxury. The choice to associate the brand with such a powerful mythological figure helped define Versace’s unique identity and differentiate it from its competitors. The use of the Gorgon as a symbol of beauty and strength made the Versace brand instantly recognizable and contributed to its enduring success in the fashion industry. Even today, the figure of the Gorgon continues to exert an indelible fascination on the collective imagination, both as a symbol of fear and power and of beauty and mystery. Therefore, starting with Gianni Versace and his research, here are 10 faces of the Medusa and where to meet her in the different museums in Italy.

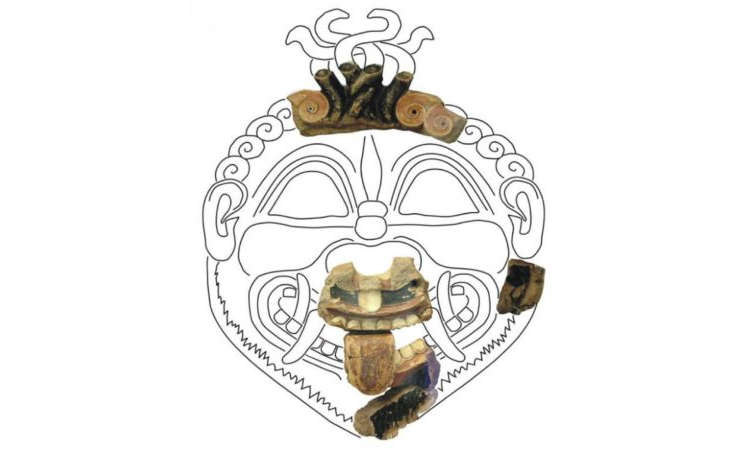

1. Great Gorgoneion - Naxos Taormina Archaeological Park.

The Great Gorgoneion, currently housed in the Naxos Taormina Archaeological Park, was discovered in several stages during excavations from 1977 to 1987 and in 1991, in the sanctuary located west of the Santa Venera stream. The fragments were found scattered over a wide area, buried in places quite far apart. The reconstructible diameter of the slab is about 1.12 meters. The size, the absence of traces of bricks on the back, and the presence of a hole for the fixing nail suggest that it may be a relief: an antepagmentum (fronton plate) positioned within the triangular space of the temple gable, similar to the large Gorgoneion of Temple C at Selinunte. Particularly unique and without comparison is the tangle of snake coils, likely completed with bronze heads, as suggested by the holes drilled in the upper part of the coils. The round curls closely resemble those of the Gorgon featured on the Syracusan slab of the Athenaion. The flowing beard has several points in common with that of the Gorgon painted on one of the Thermon metopes. In general, this figure seems comparable to some representations of the monster painted on ancient and middle Corinthian vases around 580 BCE.

2. Gorgon - Paolo Orsi Archaeological Museum, Syracuse.

The terracotta, formerly part of theAthenaion, the temple of Athena, of Syracuse in Sicily and now housed in the Archaeological Museum of Syracuse Paolo Orsi, depicts the Gorgon following the Corinthian iconographic scheme common in archaic representations of the myth. The face shows a large crescent-shaped mouth with fangs on either side, tongue hanging over the chin, wide-open eyes, and shoulder-length curly hair on the forehead. The face is always depicted frontally, while the body, squat and with two wings, assumes the posture of a running knee. Under his arm he holds Pegasus or Chrysaore, winged horses born from his body. According to Graves’ vision, Medusa would symbolize matriarchal society, supplanted by her beheading, by the patriarchal one personified by Perseus. Medusa’s mask had the function of distancing men from sacred ceremonies and mysteries reserved for women, celebrating the triple goddess Moon. Orphics also called the full moon the “Gorgon’s head,” and virgin girls wore the mask to repel the desire of men. This duality would reveal the awe and fascination of the male sex toward women, accentuated by the ancestral deity of the Mother Goddess, whose rites were concealed behind the face of Medusa.

3. Perseus decapitates Medusa - Antonio Salinas Archaeological Museum Palermo

Selinunte, the most extreme of Sicily’s Greek colonies, may have been founded in 651 B.C., the year 125 since the first Olympiad (according to Diodorus of Sicily’s date), by Megarean colonists from both Megara Hyblaea, Sicily, and the motherland Megara Nysea, Greece, under the leadership of the ecist Pammilo. Within its archaeological park was Temple C, which was part of a series of temples erected in Selinunte in the late 6th century BC. Its metopes, square tiles placed on top of the temple’s sides, were adorned with sculptures. One metope depicts the scene in which Perseus beheads the Gorgon with Athena at his side, while Pegasus, the winged horse, is born from Medusa. In the second metope, on the other hand, Heracles abducts the Kerkopes, minor demons that haunted the surroundings of Ephesus, by tying them up and hanging them on a pole. The sculptures were found during excavations in 1822. Today, the impressive remains of the temple can still be seen in Selinunte, while to this day the Medusa metope is preserved at the Antonio Salinas Archaeological Museum in Palermo.

4. Gorgon-faced Antefix - MArTA.

TheGorgon-faced Antefix, currently housed at the MArTA National Archaeological Museum in Taranto, represents a remarkable example of iconographic art from the 4th century BC. This unique piece is made of polychrome terracotta and is distinguished by its semi-elliptical shape, depicting the face of the Gorgon. Eel-like locks adorn the figure, arranged in rays around the face, while two snakes curve in the direction of the neck. Unlike the Archaic-era specimens, the expression of the Gorgon’s face in this antefix does not instill fear, but appears rather serene and composed. The dimensions of this work are 21.3 cm in height and 26 cm in width. antefixes were architectural elements used in ancient Greece and other Mediterranean civilizations. Placed on the ends of the roofs of temples and buildings, they had the function of decoration and protection, often depicting mythological figures or religious symbols. In the specific case of the antefix, the depiction of the Gorgon underscores the use of mythological elements in the art of architecture of the time.

5. Mosaic of Medusa - MANN

The mosaics section of the National Archaeological Museum of Naples (MANN) displays unique specimens from private homes in Pompeii, Herculaneum and other sites in Campania. The museum’s collection testifies to the taste and mastery achieved in this art, offering a glimpse into the most popular techniques and subjects from the second century B.C. to the first century A.D. Prominent among these works is the Medusa Mosaic that decorated the House of the Citharist in Pompeii. This large mosaic, with an area of about two meters by two meters, constituted the opus tessellatum floor decoration of the Pompeian domus. The house reached the size we see today in the first century B.C. and owes its name to the discovery of a bronze statue of Apollo playing the zither. Belonging to members of the very powerful Popidii family, as suggested by the graffiti and electoral inscriptions found in the house, it offers a valuable insight into the life and culture of ancient Pompeii.

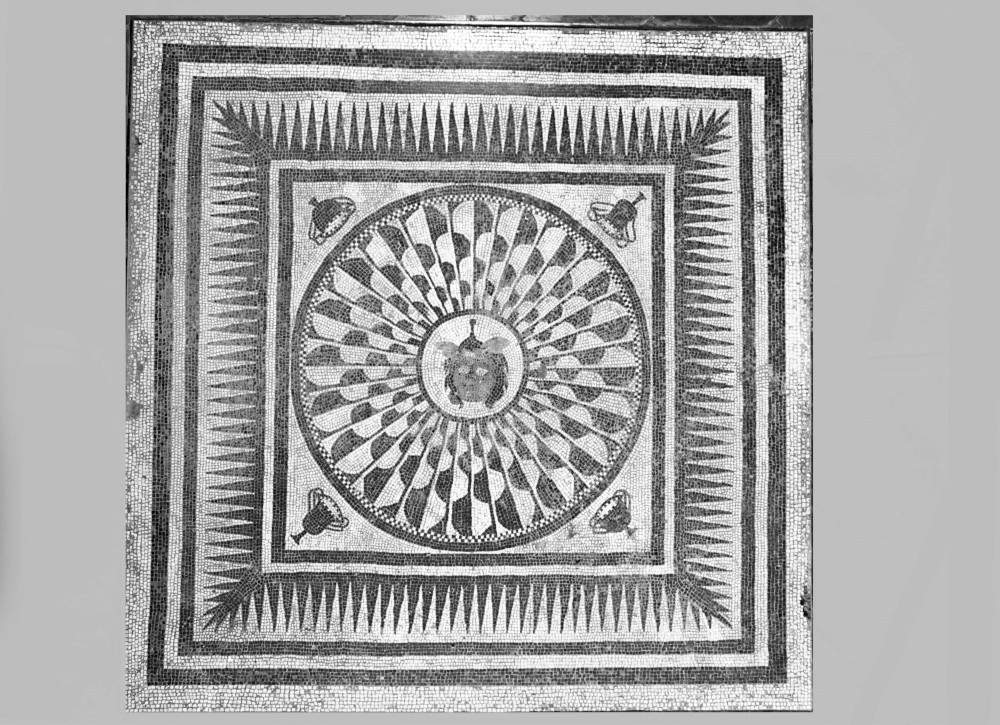

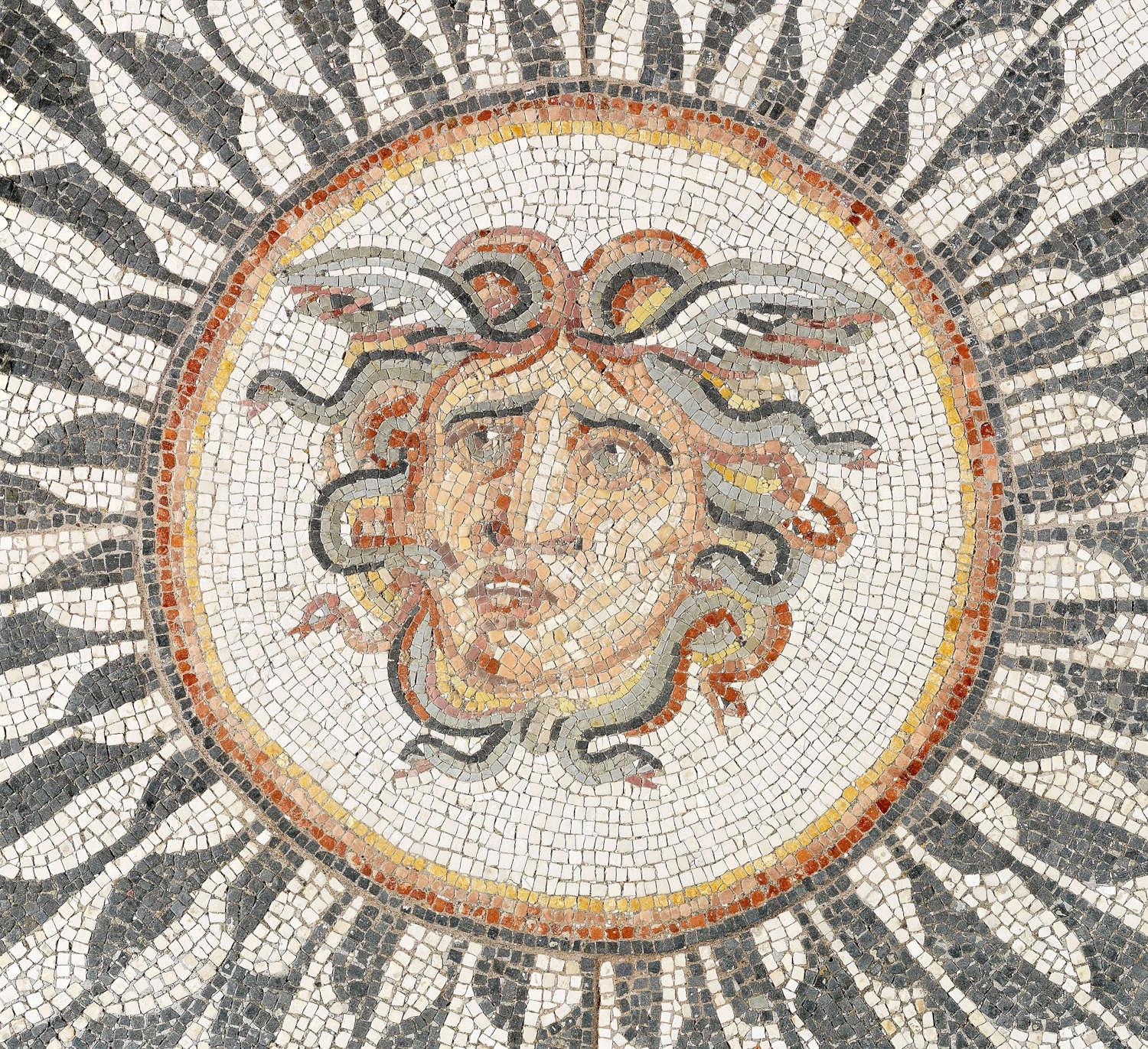

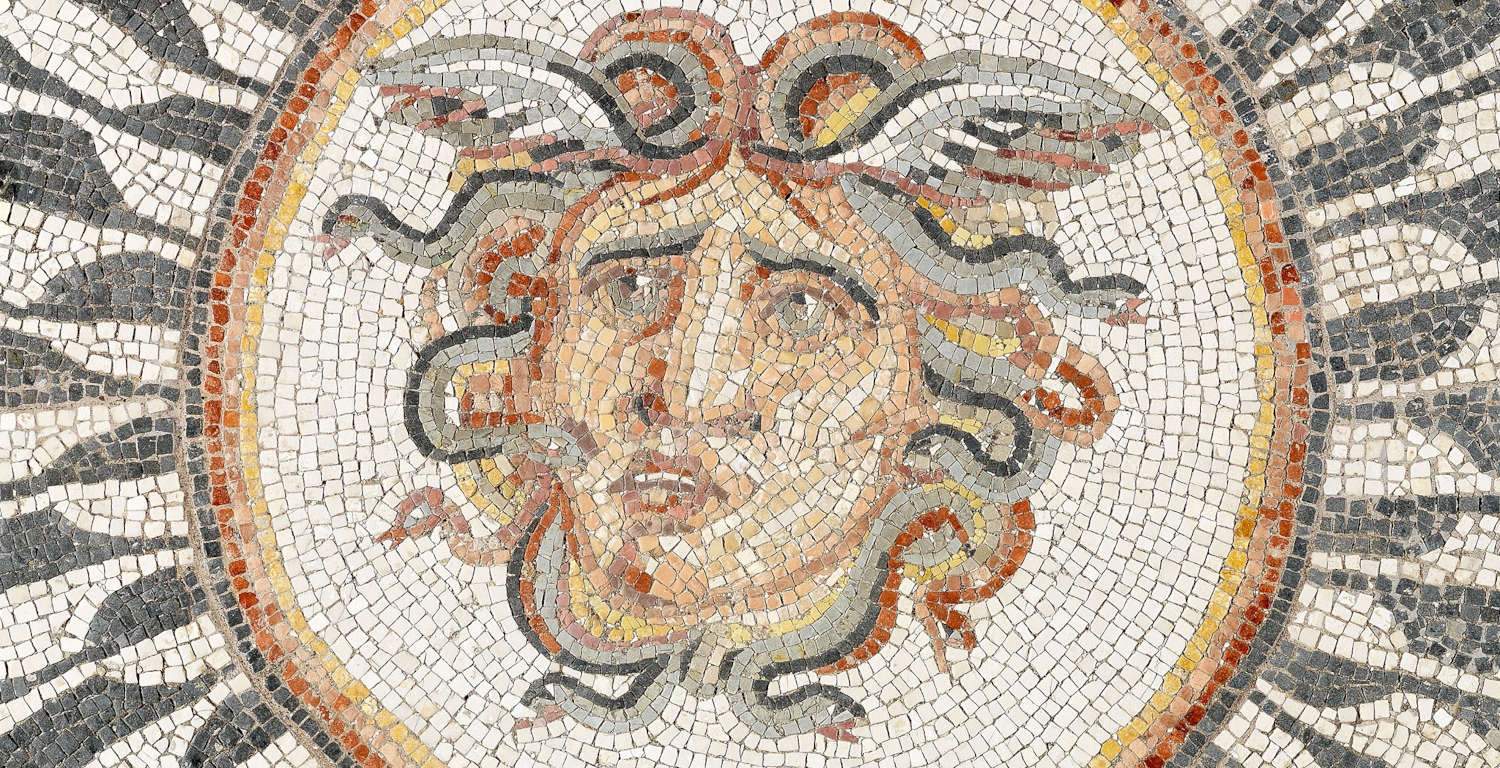

6. Mosaic with the head of Medusa - National Roman Museum, Rome

The four floors of the Palazzo Massimo in Rome contain some of the greatest masterpieces of the entire artistic production of the Roman world, including sculptures, reliefs, frescoes, mosaics, stuccoes and sarcophagi. These works, along with the entire holdings of the National Roman Museum, come from excavations conducted in Rome and the surrounding area since 1870. One of the most extraordinary exhibits preserved in this museum is the Mosaic with the Head of Medusa. Depicted in a large clypeus with bipartite black and white scales, Medusa, one of the three Gorgons, is the snake-haired monster who petrified anyone who looked at her. Perseus was able to decapitate her with the help of Athena, to whom he gave his severed head, visible in the center of the aegis in depictions of the goddess. The mosaic is further enhanced by an ornate frame with a perspective corbel motif and four corner fillers decorated with plant elements and birds intent on pecking cherries. This work, dated to the late first or mid second century CE, offers an extraordinary example of the artistry of the Roman period.

7. Perseus with the head of Medusa (Cellini) - Loggia dei Lanzi, Florence

In 1545, Benvenuto Cellini was commissioned to create Perseus with the Head of Medusa, a monumental bronze sculptural group over 5 meters high. This work depicts the mythological hero Perseus, famous for defeating Medusa. The figure of the hero rises above the mutilated torso of Medusa, whose body appears abandoned at his feet. With his right hand he holds a sword, just used to decapitate the Gorgon, while with his left hand he raises his severed head, clutching it by the snakes that made up the creature’s hair. Completed in 1554 after nine years of strenuous work, the statue still finds its home in the Loggia dei Lanzi in Florence’s Piazza della Signoria. Cellini’s sculpture is also notable for its technical mastery: the single figure of Perseus was cast in a single casting, breaking with the 15th-century practice of casting separate pieces then welded together. The decapitated body of Medusa, the severed head of the Gorgon, and the sword wielded by the hero were cast separately and then joined to the main figure of Perseus. This approach highlights Cellini’s technical virtuosity, underscoring his extraordinary contribution to Renaissance sculpture.

8. Shield of Medusa (Caravaggio) - Uffizi Gallery.

The painting known as The Shield with the Head of Medusa, made in 1598, is an oil on canvas work housed in the prestigious Uffizi Gallery in Florence. In the work, Caravaggio (Milan, 1571 - Porto Ercole, 1610) distinguished himself not so much for his depiction of Perseus killing Medusa, but for his depiction of Medusa’s freshly severed, bleeding, wide-eyed head. Scholars believe that Caravaggio approached the Medusa theme in response to a specific cultural demand of the time. The mythological figure of the Medusa enjoyed great appreciation in the circle of the Florentine de’ Medici family and, among humanists, the Gorgon ’s head was a symbol of Prudence and Wisdom. This symbolism was widely used in art treatises of the period. Ludovico Dolce, in his 1565 Dialogue of Colors, emphasized that the figure of Medusa represented Prudence, acquired through Wisdom. Giving a work depicting Medusa was therefore considered auspicious, as it symbolized the acquisition of Prudence through Wisdom.

9. Medusa (Bernini) - Capitoline Museums.

The sculpture of Medusa, created by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (Naples, 1598 - Rome, 1680), constitutes a humanized and highly expressive interpretation of the legendary mythological figure. The work is housed in the Capitoline Museums in Rome and was made in the period between 1644-1648. According to Ovid’s account, Medusa possessed the power to petrify anyone who crossed her gaze. Bernini therefore sculpted a portrait of the Gorgon, not as a truncated head but as a torso, capturing the transitory instant of her metamorphosis. The scene depicts the creature gazing at herself in an imaginary mirror, caught in the moment when, with obvious pain and anguish, she becomes aware of her transformation into marble. According to Patrick Haughey ’s interpretation in his in Bernini’s “Medusa” and the History of Art, the sculpture expresses the pain caused by snake bites and the subsequent metamorphosis into a monster. In contrast, Irving Lavin suggests that Medusa’s face reflects a moral suffering related to the contemplation of her condition. Lavin goes further in this, proposing to consider the sculpture as a metaphorical self-portrait of the sculptor Bernini, offering a unique perspective on the artist’s personal and reflective dimension in the work.

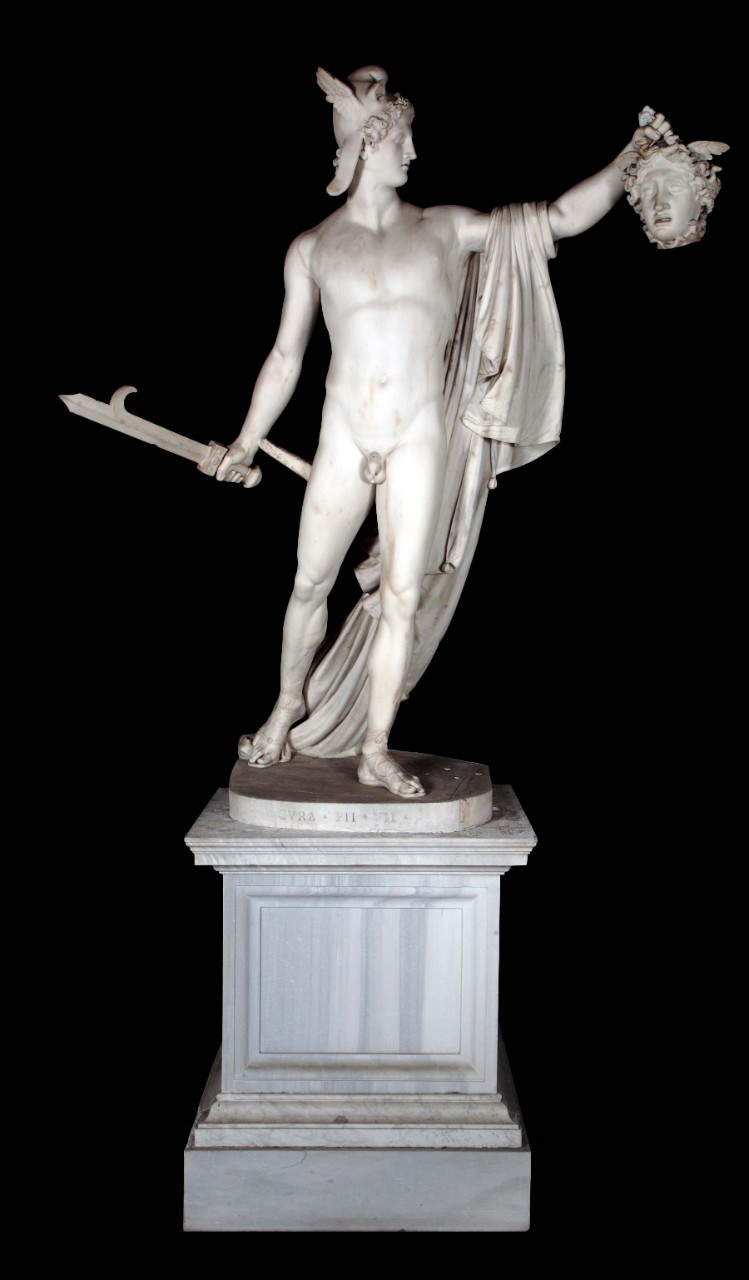

10. Perseus Triumphant (Canova) - Vatican Museums.

The sculpture of Perseus Tri umphant in the Vatican Museums in Rome, created by Antonio Canova (Possagno, 1757 - Venice 1822) between 1797 and 1801, depicts the triumphant hero after severing the head of Medusa, one of the Gorgons. Perseus is characterized by a winged headdress, Mercury’s sandals, and the sickle given to him to decapitate Medusa. The work was initially intended for the tribune Onorato Duveyriez and later given to the Cisalpine Republic for the Bonaparte Forum in Milan. Later purchased by Pius VII, it was placed on the pedestal of the Apollo del Belvedere following the Treaty of Tolentino. In terms of analysis, proportions, and expressive charge, the statue of Perseus Triumphant is inspired by the famous statue ofApollo del Belvedere, which can be dated within the mid-2nd century AD. Canova, using this source of inspiration, created a sculpture that was new in style but close to the Apollo, recalling the statue’s posture in the creative process. In 1804-1806, commissioned by the Polish countess Waleria Strynowska Tarnowska, Canova created a second version of the sculpture, now housed in the Metropolitan Museum in New York. The plaster cast of this work is preserved today at the Canova Plaster Gallery in Possagno, in the province of Treviso.

|

| The figure of Medusa in art: 10 works in 10 Italian museums |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.