The fifteenth century in San Gimignano: works and artists between Florence and Siena

Year 1353: the city of San Gimignano, until then a free commune, signed the act of submission to Florence, and the event sanctioned the end of thepolitical independence of this important center near Siena, now universally known for its towers, the most obvious symbol of the prosperity San Gimignano enjoyed in the Middle Ages, and in particular between the thirteenth century and the first half of the fourteenth century, a time when it rivaled Florence and Siena. San Gimignano, a Guelph, went through a moment of profound crisis shortly before the act of submission: torn by internal strife and devastated by the black plague of 1348, it decided to surrender itself voluntarily to Florence (which was eager to conquer this important area of Valdelsa, decisive for its own expansion toward the sea). However, paradoxically, although the 14th century was the century of the beginning of San Gimignano’s economic and political decline, it was also the century in which the arts flourished.

Moreover, although San Gimignano was politically Guelph, in artistic terms it was closer to Ghibelline Siena: in fact, the major artists active in the city in the 14th century were Sienese, starting with Memmo di Filippuccio (Siena, news 1288 to 1324), author of the very rare secular frescoes in the Camera del Podestà in the Palazzo Comunale, and father of Lippo Memmi (Siena, c. 1291 - 1356), who in 1317 painted the great Maestà in the Sala del Consiglio, strongly influenced by the one Simone Martini executed in the Sala del Mappamondo in Siena’s Palazzo Pubblico. And the sculptors Tino di Camaino (Siena, c. 1280 - Naples, 1337) and Goro di Gregorio (Siena, documented from 1311 to 1326), the authors of numerous sepulchral monuments in the city, now lost or dismembered, were also Sienese. And even after the subjugation to Florence, the influx of Sienese artists did not stop, such as Bartolomeo Bulgarini (Siena, c. 1300 - 1378), author of the polyptych on the high altar of the church of the Santissima Annunziata convent, and such as Bartolo di Fredi (Siena, c. 1330 - 1410), to whom we owe the frescoes in the church of Sant’Agostino. And Sienese were also the sculptors Giovanni di Cecco (to whom the baptismal font in the Collegiate Church is due) and Francesco di Valdambrino (Siena, c. 1375 - c. 1435), to whom the wooden Saint Anthony Abbot in the Museum of Sacred Art has been attributed.

If, however, the vicissitudes of San Gimignano’s 14th-century art are well known, and they are the ones that have also become most fixed in the public’s imagination (linking the city to the 14th century), the artistic evidence of the 15th century is less famous. Less famous, but no less interesting, partly because they continue the events of the previous century. If in the first part of the century, in fact, San Gimignano still saw Sienese painters and sculptors arrive, such as Taddeo di Bartolo (Siena, 1362 - 1422) and Jacopo della Quercia (Quercegrossa, 1374 - Siena, 1438), in 1448 the altarpiece executed by Sano di Pietro (Siena, 1405 - 1481) for the collegiate church (commissioned by Angelo di Bartolomeo Ridolfi) marks a watershed, being the last work made by a Sienese to be found in San Gimignano. In the mid-15th century, in fact, there was a reversal and the artists active in the city would all become Florentines, beginning with Benozzo Gozzoli (Benozzo di Lese di Sandro; Scandicci, 1420 - Pistoia, 1497), called in 1464 to paint the Stories from the Life of St. Augustine in the church of Sant’Agostino, thus sanctioning the arrival of the Florentine Renaissance in San Gimignano, whose artistic history continued with the works of artists such as Giuliano da Maiano, Domenico del Ghirlandaio, the Della Robbia, Piero del Pollaiolo, and Filippino Lippi. What brought about the sudden change of focus? Perhaps, the success of Benozzo Gozzoli and his important entrances (he was the Medici’s artist: the decoration of the sumptuous Chapel of the Magi in Palazzo Medici-Riccardi in Florence, then the residence of the Medici, is due to him). But it is probably also due to the fact that San Gimignano was chosen by Florentine high society as a place of residence outside the city, especially in times of plague. In this itinerary in and around the city, beginning with the Museums of San Gimignano (Palazzo Comunale, Pinacoteca, Torre Grossa, part of the Fondazione Musei Senesi), we go in search of the most interesting works of the 15th century in San Gimignano, beginning with some works from the late 14th century that can, however, fit into the groove of the late Gothic trends that continued into the next century.

The

The The Picture Gallery of

The Picture Gallery of The Picture Gallery of

The Picture Gallery of1. Mariano d’Agnolo Romanelli, Reliquary bust of a saint, possibly St. Ursula (1380-1390; carved and painted wood; San Gimignano, Musei Civici, Pinacoteca)

Made by the Sienese goldsmith and sculptor Mariano d’Agnolo Romanelli (Siena, documented 1376 to 1391), an artist active in the building site of the chapel in Piazza del Campo, it was probably painted by Andrea di Bartolo. The bust has been recognized as the work of Mariano d’Agnolo Romanelli by the scholar Alessandro Bagnoli, who has reconstructed part of the activity of this artist, who was also the author of another interesting reliquary bust, that of St. Mark Pope dated 1381 and preserved in Abbadia San Salvatore. One of the most outstanding artists of late 14th-century Siena, Mariano d’Agnolo was not an innovator, however, but preferred to recover older models (going so far as to borrow solutions from the statuary of Giovanni Pisano). The bust of San Gimignano is distinguished by a certain degree of naturalism and accuracy in the surface workmanship, the latter one of the hallmarks of Mariano d’Agnolo Romanelli’s work.

2. Taddeo di Bartolo, Saint Gimignano enthroned, stories of life and miracles (1401; tempera on panel; San Gimignano, Civic Museums, Pinacoteca)

Taddeo di Bartolo executed this panel as an antependium (i.e., a covering) for the high altar of the Collegiata (today it is instead in the Pinacoteca Civica). In the center stands out the figure of San Gimignano holding in his hands the model of the city (from which we also realize how many towers it must have had at the time). Around it, compartments narrate episodes from the life of the saint, a native of Modena. The order in which the episodes are illustrated is quite unusual (perhaps the panels were reassembled in ancient times without following a logical path): the reading starts from the right, with the scenes featuring young Gimignano in his native Modena, while on the left we see the posthumous miracles, which occurred in Tuscany. Taddeo expresses himself with a pronounced narrative verve that is especially noticeable in the scenes of the saint’s life and is reinforced by the volumetries of the figures. The Pinacoteca also holds a Virgin and Child by Taddeo di Bartolo, also from the Collegiate Church.

3. Lorenzo di Niccolò di Martino, Sportelli di tabernacolo (1402; tempera on panel; San Gimignano, Musei Civici, Pinacoteca)

A work of Florentine ambit and late Gothic taste, it was commissioned by the workers of the Collegiate Church of Santa Maria Assunta to house the relics of the local saint, Saint Fina: Fina dei Ciardi, in fact, was born in San Gimignano in 1238, to a noble family, and died here at just 15 years of age in 1253 from a serious illness, which, however, the young woman was able to overcome thanks to the strength of her faith. The doors in fact depict St. Gregory and St. Fina, while in the panels flanking the figures of the two saints (Fina, moreover, bears in her hands the model of the city) it is possible to observe the stories of St. Fina, based on a hagiography written around 1310 by Fra’ Giovanni del Coppo.

4. Master of 1419, Saint Julian between Saints Martin and Anthony Abbot (1425-1427; tempera on panel; San Gimignano, Musei Civici, Pinacoteca)

The work is attributed to a painter conventionally identified as “Master of 1419,” a name derived from the date of a painting now in Cleveland, and produced by the same hand. It is a large triptych with Saint Julian in the center and Saints Martin on the right and Anthony Abbot on the left on either side. Made between 1425 and 1427, it reveals manners that are still late Gothic, with its gold background and elongated, elegant figures, but also with an openness to the very latest Florentine innovations introduced by the works of Masaccio and Masolino. Recent studies have proposed identifying the Master of 1419 with Battista di Biagio Sanguigni, a Florentine miniaturist and painter who was a pupil of Lorenzo Monaco and probably also a master of Beato Angelico.

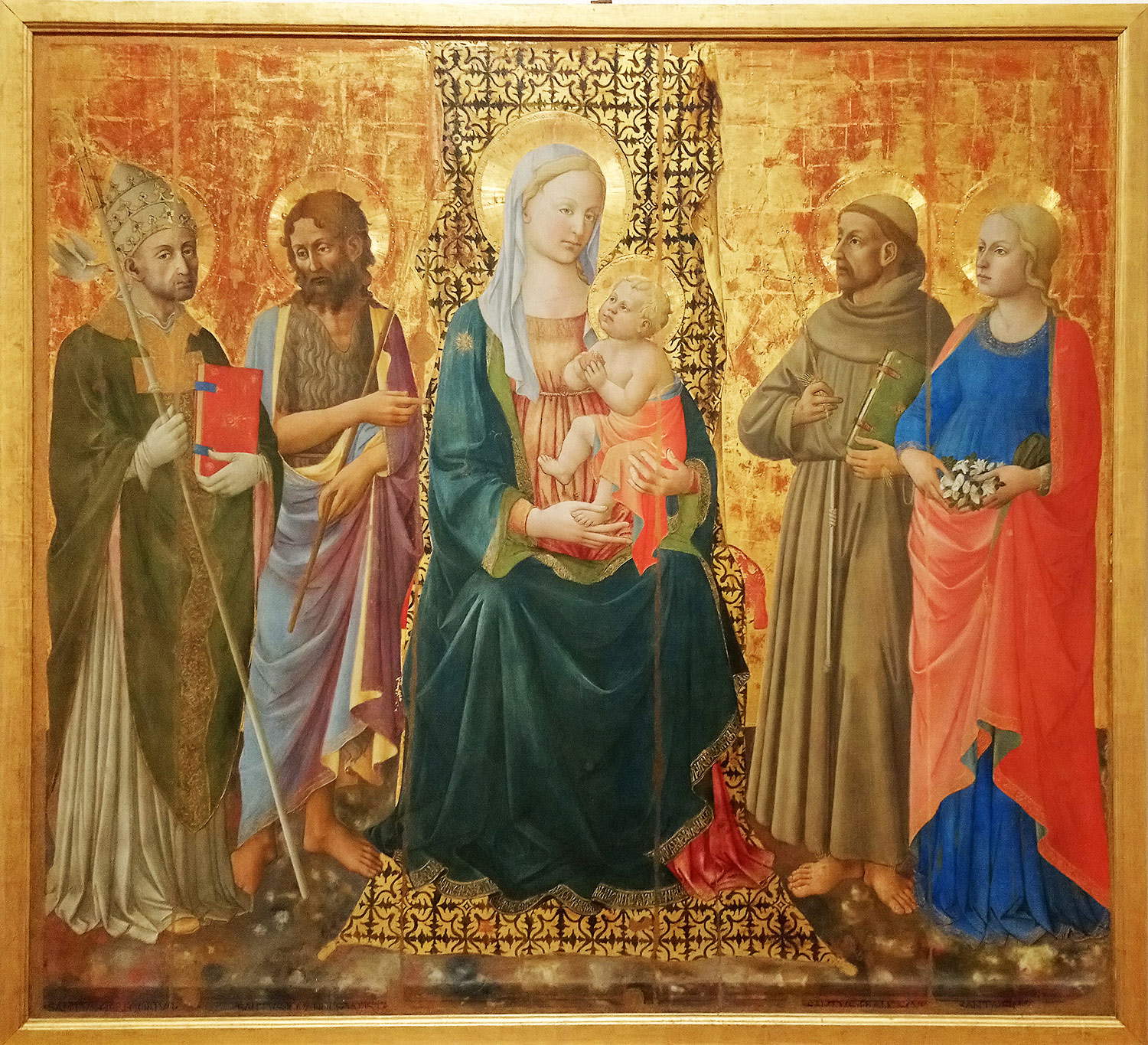

5. Domenico di Michelino, Madonna and Child with Saints Gregory the Great, John the Baptist, Francis and Fina (1463-1465; tempera on panel; San Gimignano, Musei Civici, Pinacoteca)

It comes from the church of San Michele a Casale, is the work of the Florentine Domenico di Michelino (Florence, 1417 - 1491), and is one of the earliest attestations of the Florentine Renaissance in the city, although the artist worked in ways still close to an older taste, as can be seen from the gold background of the panel: it is, after all, a work of traditional style, created for a provincial patronage. The work was rediscovered in the 19th century, but there is little doubt that it came from the parish of Casale, since the painting depicts John the Baptist, patron saint of the chapel of the powerful Salvucci family of San Gimignano.

6. Benozzo Gozzoli, Madonna and Child with Saints Andrew and Prospero (1466; tempera on panel; San Gimignano, Musei Civici, Pinacoteca)

The first great Florentine artist active in San Gimignano and the painter who brought the Florentine Renaissance to the town, Benozzo Gozzoli, who stayed in San Gimignano for about four years while having to work on the frescoes of Sant’Agostino, is present in the Pinacoteca Civica with a Madonna and Child with Saints Andrew and Prospero from 1466 (commissioned of him for the church of Sant’Andrea by the priest Girolamo Niccolai) as well as with a Crowned Madonna and Child with Saints John the Baptist, Mary Magdalene, Augustine and Martha executed for the church of Santa Maria Maddalena, also made in 1466. Both panels, which are notable for their formal elegance, were executed by Benozzo Gozzoli while he was working on frescoes in the church of Sant’Agostino and the Collegiata. In the Collegiata, see the fresco with the Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, dated and signed 1465, while in Sant’Agostino are the frescoes, also dated 1465, with the Stories of Saint Augustine.

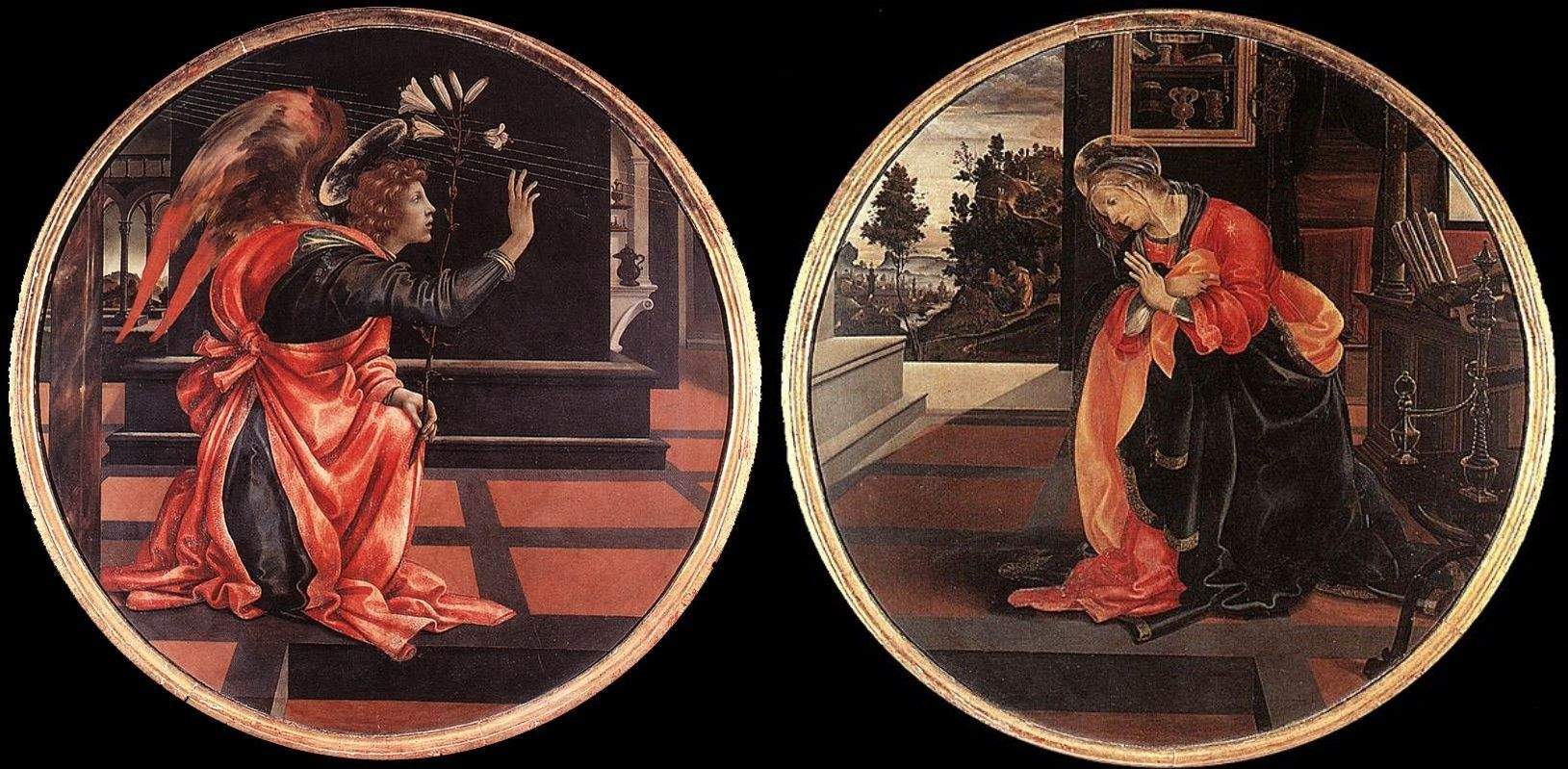

7. Filippino Lippi, Virgin Annunciate and Announcing Angel (1482; tempera on panel; San Gimignano, Musei Civici, Pinacoteca)

Filippino Lippi’s two tondi are among his most interesting works ever and were commissioned by the Priors and Captains of Parte Guelfa for the Sala delle Udienze in the Palazzo Comunale (a lay commission, then). They are youthful works, executed when Filippino was only twenty-six years old, between 1483 and 1484 (the frames, on the other hand, are later, dating from around 1490), and they fit into the groove of the painting of Sandro Botticelli, the artist Filippino most looked to at this stage of his career, while already standing out for their precious formal refinement, for the very careful study of light, for the elegant setting, and for the finishing touches inspired by Flemish art. In 2019, the two tondi were loaned to the City of Milan for the traditional Christmas exhibition at Palazzo Marino.

8. Taddeo di Bartolo, Last Judgment (1393; fresco; San Gimignano, Collegiate Church of Santa Maria Assunta)

The Sienese artist Taddeo di Bartolo worked in the Collegiata where some of his illustrious fellow citizens had already worked in the early part of the century: Lippo Memmi, Memmo di Filippuccio, Francesco di Segna, and Bartolo di Fredi. Taddeo di Bartolo was called at the end of the fourteenth century to complete the frescoes with the decoration on the counter-façade, for which scenes of the Last Judgment were planned, which are distributed around the Collegiate rose window and continue on the adjoining walls with Paradise on the left andHell on the right. The artist executed the frescoes in a short time, since by 1395 he was already documented in Pisa, where he was commissioned to paint an altarpiece for the local church of San Francesco (now preserved in Budapest). The frescoes on the counterfaçade of the Collegiate Church of San Gimignano are among the most powerful achievements of the period.

9. Jacopo della Quercia, Announcing Angel and Virgin Announced (1421-1426; painted and carved wood; San Gimignano, Collegiate Church of Santa Maria Assunta)

Jacopo della Quercia’s two wooden sculptures, commissioned for the chapel of Saints Fabian and Sebastian in the Collegiate, were made by the Sienese sculptor in 1421 and then painted by Martino di Bartolomeo in 1426. Masterpieces of Sienese sculpture, they are presented as works in which Jacopo della Quercia gives substance to his ways that anticipate Renaissance art. The two sculptures, which form a single Annunciation group, are of extreme importance because they constitute the only documented wooden sculptures by Jacopo della Quercia. Moreover, the catalog of this great sculptor’s wooden production has been enriched with new attributions only in recent years and is the subject of constant critical attention.

10. Domenico del Ghirlandaio, Giuliano da Maiano and Benedetto da Maiano, Chapel of Santa Fina (1468-1475; sculpture and frescoes; San Gimignano, Collegiate Church of Santa Maria Assunta)

A masterpiece of the Florentine Renaissance, the chapel that houses the relics of the saint from San Gimignano was designed in 1468 by Giuliano and Benedetto da Maiano, and then decorated in 1475 with frescoes by Domenico del Ghirlandaio, who painted the stories and miracles of saint Fina on the chapel walls. This was the first major commission received by the great Florentine artist. The chapel altar also serves as a sepulchral monument that houses the saint’s remains, and is the work of Benedetto da Maiano from 1475. A curiosity: on the tomb of St. Fina is an inscription (“Miracula quaeris? / Perlege quae paries vivaque signa docet / MCCCCLXXV,” meaning, “Are you looking for miracles? / Observe those that the walls and vivid images illustrate / 1475”?).

11. Benedetto da Maiano and Sebastiano Mainardi, Chapel of San Bartolo (1492-1495; sculpture and frescoes; San Gimignano, Church of Sant’Agostino)

San Bartolo is another of the saints venerated in San Gimignano (as well as another native saint of the town, who lived between 1228 and 1310), and the chapel that was decorated between 1492 and 1495 is dedicated to him: Sebastiano Mainardi, Ghirlandaio’s brother-in-law, was in charge of the frescoes (painting, in the vault, the doctors of the church namely St. Ambrose, St. Augustine, St. Jerome and St. Gregory, while in the wall adjoining the altar Sts. Gimignano, St. Lucy and St. Nicholas of Bari), while Benedetto da Maiano was in charge of the marble altar. The chapel also features an interesting majolica tile floor by Andrea della Robbia.

12. Piero del Pollaiolo, Coronation of the Virgin with Saints and Musician Angels (1483; tempera on panel; San Gimignano, Church of Sant’Agostino)

A work of the late 15th century, the high altarpiece depicting theCoronation of the Virgin with Saints and Musician Angels, sandwiched between Benozzo Gozzoli’s frescoes illustrating the stories of St. Augustine, is one of the most interesting works by the Florentine Piero del Pollaiolo. It dates from 1483 and was commissioned by the Augustinian Domenico Strambi as an altarpiece for the high altar of the church of Sant’Agostino (the commission probably came through Antonio del Pollaiolo, Piero’s brother, who was in the city in 1480). It is sharply divided into two registers: in the upper one we witness the coronation of the Virgin by Jesus, with musician angels around him accompanying the event. In the lower one six saints are arranged, observing what is happening above them: they are Saint Fina, Saint Augustine, Blessed Bartolo da San Gimignano, Saint Gimignano, Saint Jerome, and Saint Nicholas of Tolentino. Note the chalice of the Eucharist, held by three cherubs, acting as a link between the two registers of the composition.

|

| The fifteenth century in San Gimignano: works and artists between Florence and Siena |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.