The 10 must-see exhibits at the Egyptian Museum in Turin

The Egyptian Museum of Turin, founded in 1824 by King Charles Felix of Savoy, is one of the most prestigious Egyptian collections in the world outside Cairo. Since its creation inside it found space for the first antiquities from the Drovetti Collection, purchased by King Charles Felix. The building later underwent extensions and adaptations in the nineteenth century, but it was not until 1832 that it opened to the public. In addition to Egyptian artifacts, the museum housed Roman, pre-Roman and prehistoric artifacts, as well as a section devoted to natural history. With more than 30,000 artifacts, recovered between 1903 and 1937 from archaeological excavations conducted in Egypt by Ernesto Schiaparelli and then Giulio Farina, it offers an interesting look through ancient Egyptian civilization. To date among its treasures is the Hall of Statues, an impressive display of monumental sculptures, including the statue of Ramses II and the seated statue of Cheops. The museum boasts an extensive collection of mummies, including that of Kha and Merit, perfectly preserved along with their grave goods. The museum tour runs through thematic sections covering all aspects of Egyptian life, from art and religion to daily life and death. The Papyrus of Artemidorus, a valuable astrological document, and the Papyrus of the Book of the Dead, with its formulas for travel to the afterlife, are just some of the documents that tell the story of the spirituality and beliefs of the ancient Egyptians.

In addition to the exhibits, the museum also offers a multimedia experience with projections, virtual reconstructions and interactive workshops that allow visitors to deepen their knowledge of ancient Egypt. The museum’s location, the Palace of the Academy of Sciences, provides a particularly impressive backdrop for the exhibits. Over the years, the museum has continued to expand, with new acquisitions and restoration projects keeping the legacy of ancient Egypt alive. Therefore, we have selected the ten must-see exhibits of the Egyptian Museum of Turin. Which ones are they? Let’s find out together.

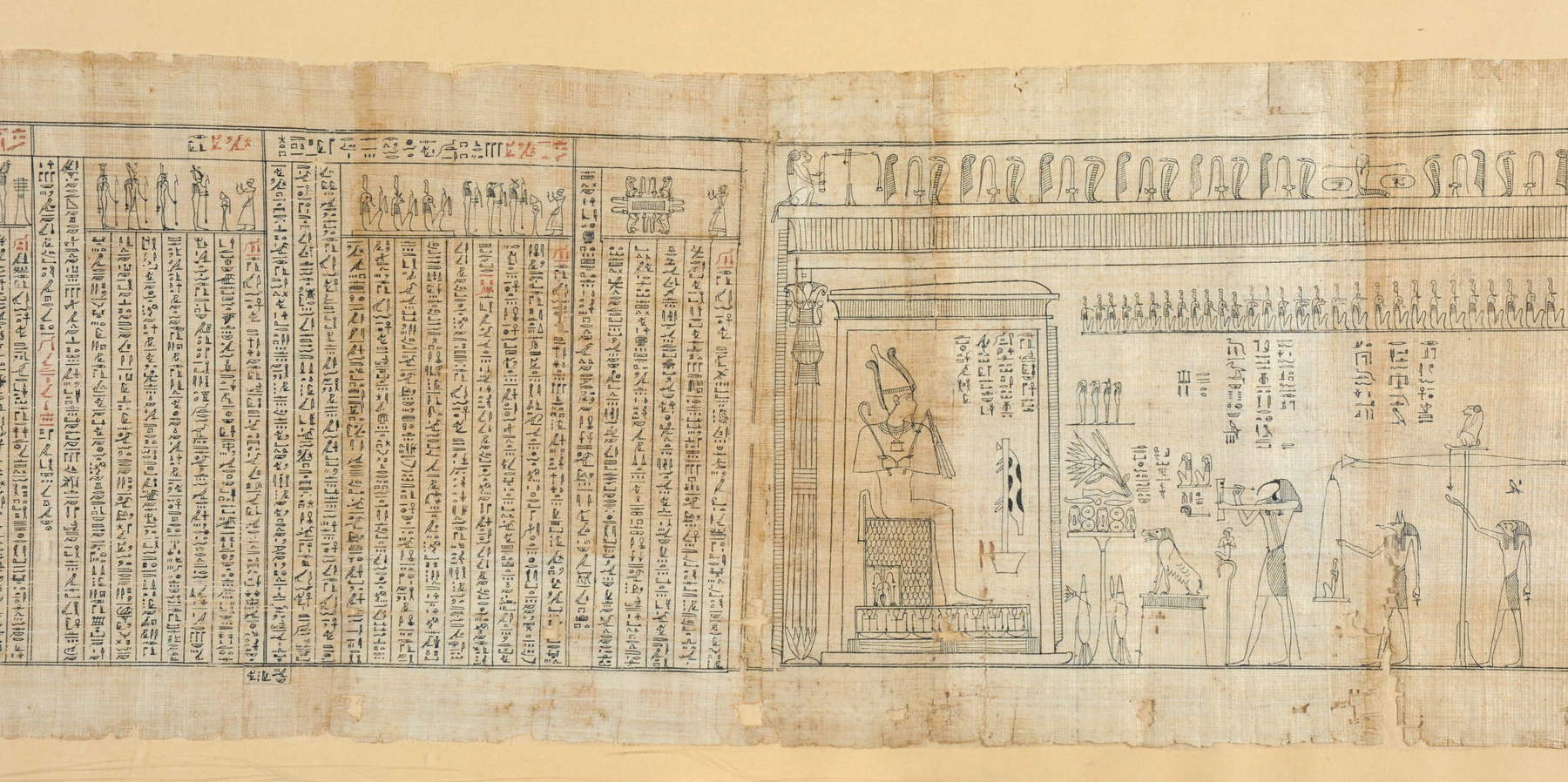

1. The Book of the Dead of Iuefankh.

The Book of the Dead of Iuefankh is a document dating from theHellenistic period, written on Cyperus papyrus. The manuscript, dated between 332 and 30 BCE, was discovered in the region of Thebes and acquired in the Drovetti Collection in 1824. Its current location is in Room 01, Frame 01. The Book of the Dead was a spiritual guide and compendium of spells and formulas, designed to assist the deceased on their journey through the afterlife and ensure passage to the realm of the dead. The text contains detailed instructions on ritual practices to be followed during the mummification process, such as invocations to the gods to assist the deceased in their journey to the afterlife. These magical formulas were considered essential to protect the soul of the deceased from the pitfalls of the underworld and ensure their eternal life. Its discovery and preservation represent a cultural heritage of rare value, allowing a fundamental part of Egypt’s history to be preserved and studied.

2. Statue of female deity (Hathor or Isis), so-called “Isis of Coptic.”

The statue of the female deity, commonly known as the CopticIsis, is a work of art carved from granodiorite stone. The statue dates from the New Kingdom period ofancient Egypt, specifically the 18th Dynasty, a time of fervent artistic and cultural activity. It is dated between 1539 and 1292 BCE, witnessing a rich era that shaped the religious consciousness of ancient Egypt. Her identity is often associated with Hathor or Isis, deities worshipped in the ancient Egyptian pantheon, symbols of fertility, love, motherhood and protection. Coptic Isis embodies the very essence of divine femininity, with her delicate features that seem to peer into the souls of observers. The sculpture’s provenance traces back to Copto, an ancient city in Egypt, or perhaps to the temple of Min, an important Egyptian god associated with creation and prosperity. Acquisition of the statue The Donati Collection acquired the statue which is now located in Room 01 on plinth 03.

3. Pleated tunic

The pleated tunic is an ancient garment that dates back to the Old Kingdom period of Egypt, specifically between 2435 and 2118 BCE. The garment was found in Assiut and acquired by Ernesto Schiaparelli, and is a valuable find in the history of human clothing. Made of linen, a common material in ancient Egypt for its freshness and lightness, this tunic features pleats or pleating that give it a distinctive appearance. The pleated workmanship not only adds visual interest to the garment, but may also have had practical purposes, such as facilitating movement or regulating body temperature in a hot climate like Egypt’s. The garment, placed in Room 02, Showcase 15, offers a glimpse into the fashion and textile techniques of antiquity, highlighting the craftsmanship of the people of Egypt in creating functional and aesthetically pleasing garments.

4. The Dancer’s Ostrakon

TheOstrakon, a fragment of stone or pottery used as a support for drawing or writing, of the dancer in an acrobatic position is a New Kingdom work, precisely dating to the period between 1292 and 1076 BCE. Made of limestone and adorned with paintings, this piece comes from Deir el-Medina, an archaeological site known to have been the home of tomb workers in the Valley of the Kings. The dancer depicted on this ostrakon captures the movement of her body as she contorts herself into a posture that requires strength, flexibility and a profound sense of balance. The details of her carefully painted robes and the attention to detail in the rendering of her facial features reveal the artistry of the creators of this fragment. Its acquisition occurred in 1824, when it became part of the Drovetti Collection and to this day, it is displayed in Room 06, Showcase 06, where it attracts the attention of scholars, history buffs and the merely curious.

5. Chapel of Maia

The Chapel of Maia, found in the necropolis of Deir el-Medina in 1906, was discovered by Ernesto Schiaparelli’s archaeological mission. Its walls, composed of mud and straw bricks, are covered with plaster on which dry tempera paint was applied. The colors, derived from minerals and vegetables such as ochre, charcoal and malachite, are mixed with water and acacia gum as a binder. The paintings’ exceptional preservation allowed restorer Fabrizio Lucarini to transport them to Italy in 1906, using the technique of tearing to detach the painted plaster. Although this method requires considerable skill, it allows the painting to be preserved in its entirety without damaging it. Dating back to the New Kingdom, the chapel, dated between 1353 and 1292 B.C., is a valuable artifact of the 18th Dynasty, now displayed in Room 06, Showcase 11, a witness to Egyptian wall painting technique.

6. Wig of Merit

Merit’s wig is a piece in the collection that gives an up-close look at the cosmetics and fashion of the period. The hairstyle was made from strands of human hair, skillfully sewn and braided to create a hairstyle that embodies the elegance of the ancient kingdom. The wig features a central parting, dividing the locks into two sections while the hair is curled into ringlets ending in braids. The hairstyle style was particularly popular during the mid-18th Dynasty, as depictions from the period show. What makes this wig even more interesting, however, are the ornamental details: often adorned with flowers and tiaras, it conveys a sense of sophistication typical of the Egyptian elite of the time. Found in the tomb of Kha (TT8) at Deir el-Medina, the wig has been dated to between 1425 and 1353 BCE, during the New Kingdom. It was later acquired by Ernesto Schiaparelli and is now displayed in Room 07, Showcase 08, where through its charm it continues to capture the interest of visitors.

7. Statue of Ramesses II

The image of ruler Ramesses II wears the khepresh crown while clutching the heqa scepter to his chest, symbols of his sovereign power while under his sandals, the Nine Arches, symbols of his defeated opponents, attest to his supremacy. On either side of the throne, the figures of his wife Nefertari and son Amonherkhepeshef express the dynastic continuity and family bond of the ruler. The face of the statue, with obvious similarities to the predecessor Seti I, suggests a probable stylistic evolution during the reign of Ramesses II. However, there are no signs of rework, suggesting that it may have been created early in his reign. The presence of Queen Nefertari therefore indicates that one is in the first half of the reign of Ramesses II. The work has also become one of the icons of the Egyptian Museum, and French archaeologist Jean-François Champollion himself called the sculpture “the Apollo of the Belvedere of Egyptian art.” The statue, carved in stone or granodiorite, was found in Thebes, in the temple of Amun at Karnak. In 1824, the statue became part of the Drovetti Collection. Currently, it can be viewed in Room 14, Basement 05 of the Egyptian Museum.

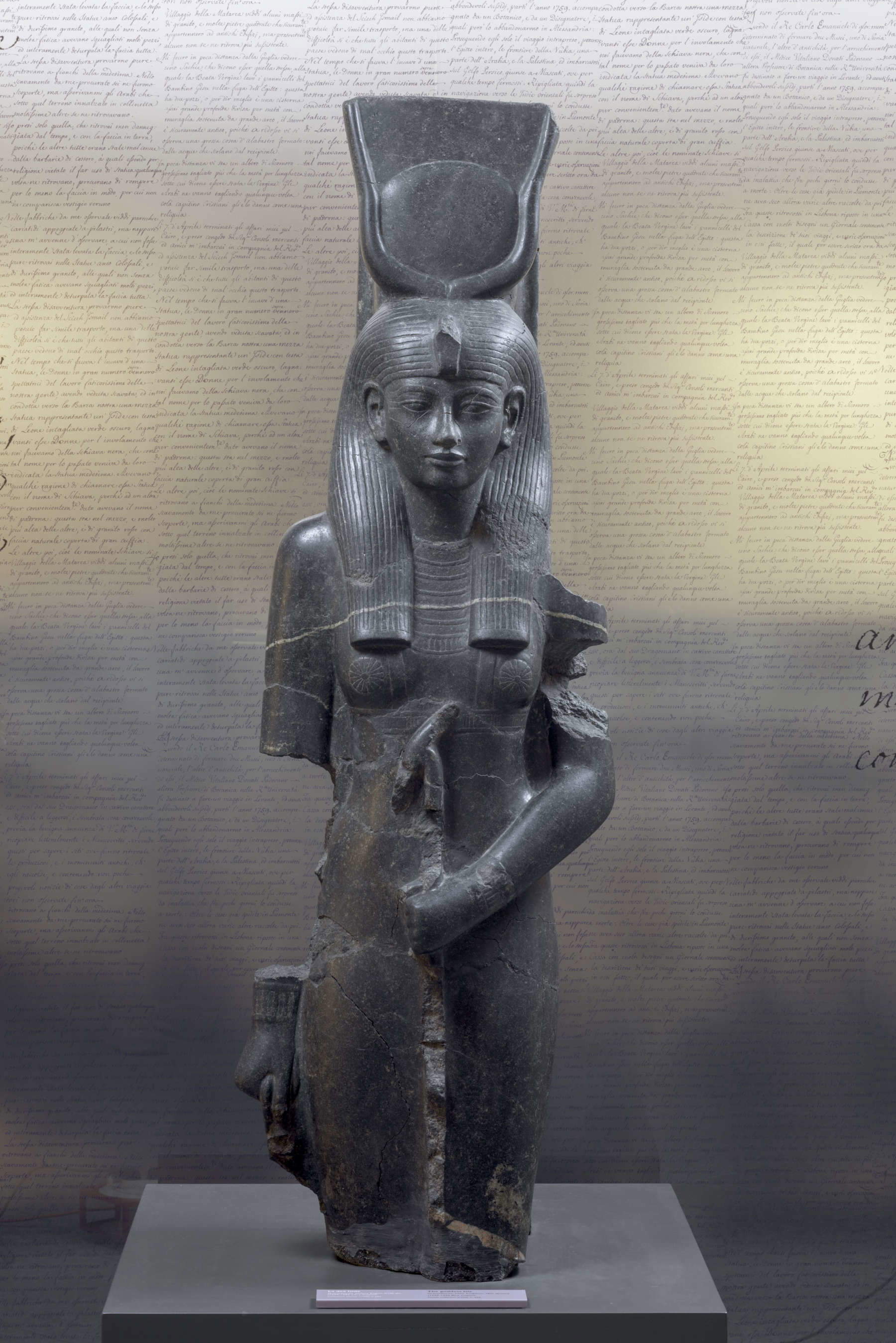

8. Statue of Seti II

The statue of Seti II, is an example of monumental statuary that succeeds in embodying the power and stability of the ruler. It is a detailed structure and geometric lines that conveys a sense of strength and authority through the left leg placed forward, a symbol of his power to move and act. In the depiction, the king holds a banner adorned with the insignia of the god Amun, dominant at the upper end. Formerly placed next to another similar statue, now in the Louvre, the sculpture originally guarded the entrance to a chapel in the vast courtyard of the temple of Karnak, erected at the behest of Seti II himself. Made of sandstone, its presence dates back to the New Kingdom period, specifically the 19th dynasty, around 1202-1198 BCE, testifying to its status as a significant piece in historical collections. Acquired in 1824 from the Drovetti Collection, the statue is now located in Room 14, on plinth 11.

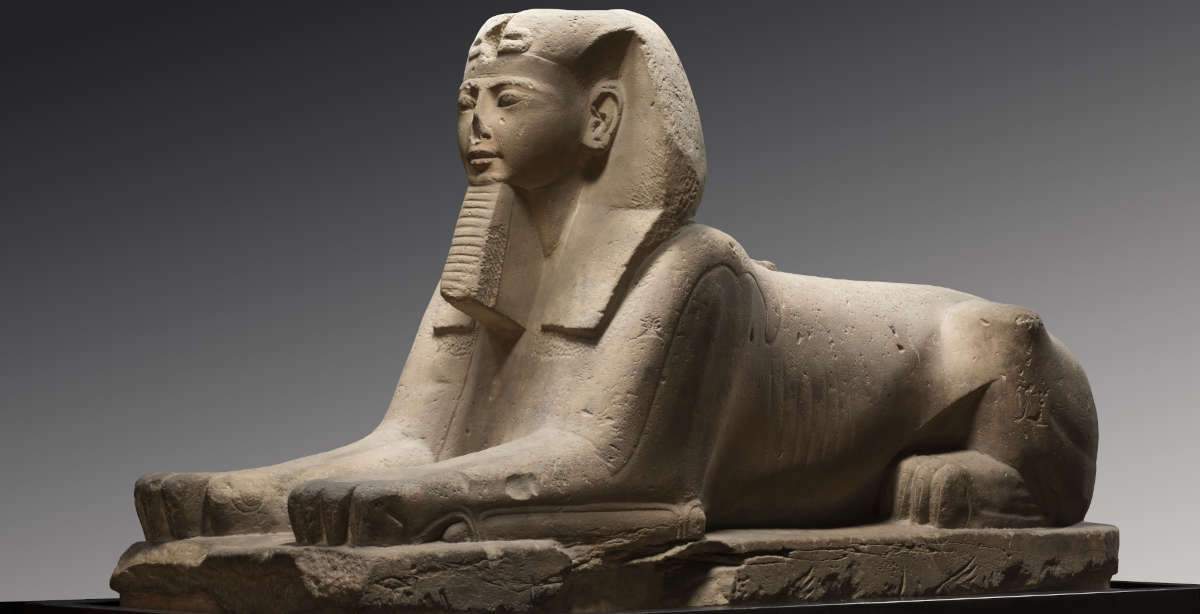

9. The Predynastic Mummy.

In ancient Egypt, the representation of the pharaoh and queen could also take the form of a sphinx, a mythological animal that had the body of a lion and a human face. This hybrid image communicated the idea of the strength of the lion, an animal associated with the Sun god, to the rationality of the human being. Sphinxes were usually placed, in pairs, at the entrances to temples, along processional avenues or at the entrance to certain halls, and they filled the role of guardians. The sphinx from the temple of Amun is from the Ramesside period: we can tell from details such as the shape of the eyebrows, the almond-shaped eyes, and the full lips. The Sphinx from the Temple of Amun is located in Room 14, on plinth 20.

10. Temple of Ellesiya

The Temple of Ellesiya, commissioned by Tutmosi III in 1454 BCE, stands on the banks of the Nile River, not far from Abu Simbel, in the heart of Nubia. Carved into the rock, the temple is a tribute to the Horus gods of Miam and Satet, reserved only for those who reach it by water. The inverted T-shaped arrangement of the interior, with a corridor and two side chambers, accommodates scenes of votive offerings by the ruler to Egyptian and Nubian gods, such as Horus, Satet and the king himself, Thutmosi III. With the passage of centuries and the advent of Christianity, the walls accommodate engraved crosses and five-pointed stars testifying to a spiritual transformation. Today, threatened by the waters of Lake Nasser, the temple is the focus of preservation efforts led byUNESCO. After spending centuries in the heart of Nubia, in 1967 the temple found a new home in Turin, where it was carefully reconstructed in the wing of the museum dedicated to Ernesto Schiaparelli. Acquired as a gift to the Egyptian government in 1966, the Temple of Ellesiya was transported and placed in Room 15.

|

| The 10 must-see exhibits at the Egyptian Museum in Turin |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.