Gian Lorenzo Bernini (Naples 1598 - Rome 1680) is the leading figure of seventeenth-century European Baroque figurative culture. In his artistic career he distinguished himself among Roman artists, earning a prestigious reputation with the popes and leading figures of his time. As a great interpreter of the culture of the period, Bernini was able to create works that marked the history of art and were able to excite and amaze viewers. Endowed with innate charm and brilliant eloquence, he embodied a sociable and aristocratic spirit that made him an admired and respected figure. Pope Urban VIII called him “Huomo raro, ingegno sublime, e nato per disposizione divina, e per gloria di Roma a portar luce al secolo,” acknowledging his extraordinary talent and immense contribution to the art and culture of his age.

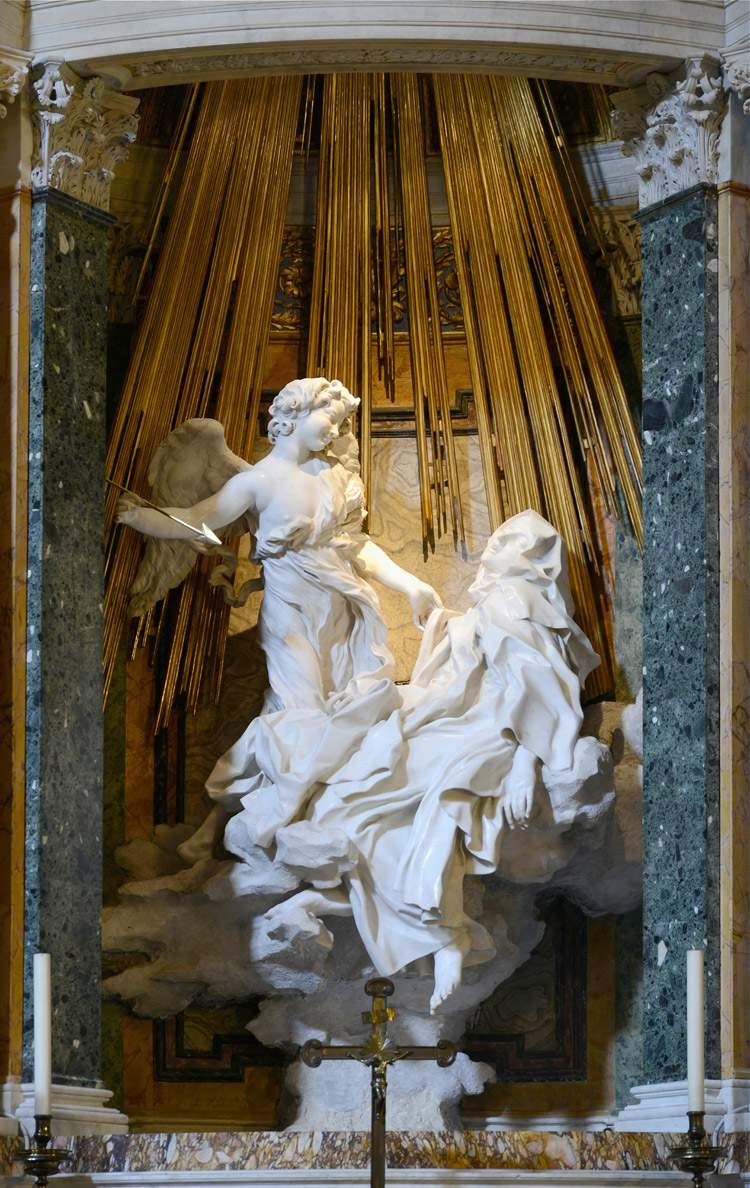

In six decades of activity, Bernini shaped many emblematic works that have marked the history of art and continue to thrill visitors. His first major sculptures, such as The Rape of Proserpine and Apollo and Daphne, created for the gardens of the Villa Borghese, immediately established him as a master sculptor, thanks to his technical virtuosity and the extraordinary expressiveness of his works. Bernini’s rise in the art world also accelerated, however, in 1623, with the election of Urban VIII to the papal throne. The pontiff, eager to promote a new artistic Renaissance, saw in the artist an heir to Michelangelo, a multifaceted genius capable of elevating art to the highest perfection. Therefore, in those years, Bernini was commissioned to decorate St. Peter’s Basilica, where he created majestic works such as the baldachin on the high altar and the monumental tomb of the pontiff himself. His artistic versatility was also expressed in the creation of theatrical sets and plays, evident in sculptural compositions such as the Transverberation of St. Teresa of Avila and theEcstasy of Blessed Ludovica Albertoni. Gian Lorenzo Bernini left an indelible imprint on the Eternal City. Here, therefore, are ten iconic works found in Rome that represent the pinnacle of 17th-century Baroque art and testify to his genius.

Inside the Galleria Borghese in Rome is the Rape of Proserpine, created in 1621-1622 in Carrara marble. The work depicts the moment of Proserpine’s abduction by Pluto, lord of the Underworld, as narrated by both Claudianus and Ovid. The myth recounts the abduction that took place on the shores of Lake Pergusa, near Enna, and the anguish of Ceres, the goddess of grain, who reduced the land to drought until Jupiter was forced to intervene so that the young woman could return to her for six months of the year. Bernini as a whole captures the climax of the action: impassive Pluto drags Proserpine into the underworld, his muscles tense in the effort as the girl writhes in an attempt to free herself, so much so that the god’s hands sink into her flesh. The entire sculptural setup seems to defy the limits of stability, with the two figures moving away from each other while maintaining frontal contact with the viewer. The maiden’s twisting recalls the virtuosity of Mannerism, but the plastic power, muscular tension, sensuality of form, and emotional intensity express an expressive language based on a naturalism evident in the material rendering of the marble. Bernini translates the poetics of myth through the careful study of classical statuary and the recovery of ancient techniques to bring this work of art to life.

In addition to the Rape of Proserpine, the Galleria Borghese preserves other works from his early period, including the celebrated Apollo and Daphne. Sculpted in Carrara marble in 1622-1625, the god is portrayed running, with his right foot firmly on the ground while his left is suspended in the air; the drapery that envelops him, over his hips and left shoulder, flows following his movement. Having reached the climax of the chase, he lays his left hand on Daphne’s body while under his divine touch, the nymph, stopped instantly in her flight with arms outstretched high and face trying to turn back, has already transformed her feet into roots and her hands and hair into laurel fronds. The subject of this sculptural group is Ovid’s famous fable from the Metamorphoses, where he tells of Apollo, struck by a golden arrow shot by Eros, falling madly in love with the nymph Daphne, a devoted follower of Diana. The young girl, however, pierced by a lead arrow, rejects the god’s love and begs her father, the river god Peneus, to transform her. The work captures the climactic moment of Daphne’s metamorphosis into a laurel tree. Initially, the sculpture was placed on the side of the room adjacent to the chapel and stood on a lower plinth than it does today, devices that amplified the work’s scenic impact and emotionally engaged the viewer.

Between 1624 and 1633, Bernini took on the role of site director for St. Peter ’s in the Basilica of the same name in the heart of the Vatican in Rome. During the period, numerous works of art were created, including the famous Baldachin. The monument, of considerable technical complexity, represents the manifesto of Baroque art thanks to its square-based architectural structure and its predominantly sculptural execution. Commissioned by Pope Urban VIII, the Baldachin stands directly above the tomb of St. Peter. The twisted bronze columns, 11 meters high, are among the first elements to catch the eye, with their gold decorations of phytomorphic motifs, inspired by nature, topped by composite capitals that add dynamism to the composition. The concave entablature, typical of the Baroque, joins the four columns through a festoon fringe, which really looks like fabric moved by the wind thanks to the mastery of bronze workmanship. The Baldachin is crowned with four statues of angels at the corners and putti holding festoons, the keys of St. Peter and the papal crown, all embellished with gilding. On one side, a putto lifts to the sky an enormous upside-down bee, the symbol of the Barberini family of Pope Urban VIII, who commissioned the work. The Baldachin also captured the admiration of great writers such as D’Annunzio, who in his “Roman Elegies” wrote “Rising sparkling through the shade are the four columns that in pagan bronze Bernini twists in coils.”

The Medusa created between 1644 and 1648 and exhibited in the Capitoline Museums in Rome offers a unique and expressive interpretation of the fearsome mythological figure. Bernini sculpts a true portrait of the Gorgon, captured in the transitory moment of her metamorphosis. Medusa, observing her reflected image in an imaginary mirror, is surprised as she becomes aware of the punishment and, before our eyes, literally transforms into marble with pain and anguish. For Bernini, Medusa becomes a sophisticated Baroque metaphor for sculpture and the sculptor’s skills, capable of petrifying those who admire his talent. Despite her monstrous nature, Bernini portrays Medusa as an attractive-looking young woman, differing from the more distant interpretation of Medusa Rondanini, who displays a cold beauty. Bernini’s version expresses slight suffering, suggesting the pain of snake bites and subsequent transformation into a monster, as speculated by Patrick Haughey. Irving Lavin points out that Medusa’s face rather expresses a moral suffering resulting from meditation on her condition. Moreover, Lavin proposes interpreting Bernini’s Medusa as a metaphorical self-portrait of the sculptor himself.

The sculptural masterpiece of the Ecstasyof Saint Teresa, housed in the church of Santa Maria della Vittoria in Rome, was created by the artist between 1645 and 1652. Commissioned by Cardinal Federico Cornaro, the marble and gilded complex includes not only the Ecstasy of Saint Theresa, but the entire family chapel. For the representation, Bernini relied on a writing of the saint who described being pierced in the heart by an angel with a spear of fire. This detail is faithfully rendered in Carrara marble: the angel holds the arrow symbolizing divine love, ready to strike the saint in ecstasy, with half-closed eyes and lips. In addition to the aesthetic complexity, the artist’s spiritual quest emerges, seeking to convey the meaning of divine love through the mystical experiences of the saints. The theatrical effect of the scene is accentuated by the surrounding aedicule, where Bernini inserted the work. On either side are boxes with stucco perspective architecture, depicting members of the Cornaro family witnessing the event. The artist also shaped the marble with mastery, giving a dramatic and dynamic effect: the saint’s dress in fact falls in a disorderly manner, as if it were wax. In this Bernini demonstrates his technical virtuosity, creating an extraordinary work that blends artistic mastery and spiritual depth.

The Fountain of the Four Rivers in Rome’s Piazza Navona, commissioned by Pope Innocent X Pamphilj as an ornament for the square during the construction of the family palace, was intended to replace a drinking trough. In 1647, the pontiff commissioned Francesco Borromini to design a new water main and decided to move it onto the square’s obelisk, which had previously been broken off and located in the Circus of Maxentius along the Via Appia Antica. After a competition in which important artists participated, the task of creating the fountain was given to master Bernini, who presented a model in silver. The fountain, in the center of an elliptical basin, represents a travertine cliff with a cave and four openings to support the granite obelisk. On the corners of the cliff are monumental marble statues of the four rivers representing the then known continents, with vegetation and animals alongside: the Danube for Europe, the Ganges for Asia, the Nile for Africa, and the Rio de la Plata for America. On the cliff are marble coats of arms of the pope’s family, with a dove holding an olive branch in its beak, and the same dove in bronze atop the obelisk. Made between 1648 and 1651 by a group of artists directed by Bernini, the Fountain of the Four Rivers is the union of architecture and sculpture, expressing movement in every detail, from vegetation to statues and fauna, becoming the focal point of the surrounding space.

In 136 AD, Emperor Hadrian erected a bridge to facilitate access to his mausoleum from the center of Rome: this ancient structure is now known as Castel Sant’Angelo. The bridge, made of travertine marble, spans the Tiber River with five arches, three of which date back to Roman times. In 1688, the bridge was further embellished with ten statues of angels, five on each side, carved by Bernini’s pupils and the master himself. Each angel bears a symbol of the Passion of Christ. Prominent among Bernini’s works are two of the angels on the bridge: theAngel with the scroll and theAngel with the crown of thorns. The original sculptures, replaced by copies by his students on the bridge, are now preserved in the basilica of Sant’Andrea delle Fratte in Rome. The Angel with the scroll bears the inscription INRI, a symbol of the title placed on the cross above Jesus’ head. The original terracotta model is kept at the Harvard Art Museums. The Angel with the Crown of Thorns, on the other hand, holds in his hands the crown that will be placed on Christ’s head. The original terracotta model of this work is on display at the Louvre Museum instead.

The Sketch of the Equestrian Statue of Louis XIV, modeled in terracotta by Bernini between 1669 and 1670 and now on display in the Borghese Gallery, depicts Louis XIV of France, known as the Sun King, in armor and holding a scepter as he rides a prancing horse supported by rocks. The preparatory sketch was made for the large equestrian statue commissioned by the king for a square in Paris. In 1669, Bernini received the marble block for the statue, but did not begin work for years. Not completed until 1677 or 1678, the sculpture remained in his studio until his death in 1680, when it was still waiting to be shipped to Paris. However, when the king saw it in 1685, he was not satisfied with it and demanded its destruction. He later agreed that it should be transformed into the depiction of the Roman hero Marcus Curtius by François Girardon. It is currently on display in the Orangerie in Versailles, while two other copies exist, one in the Louvre Museum and the other in Switzerland. The sketch, characterized by vigorous and vital modeling, clearly shows the influence of the statue of Emperor Constantine, which Bernini had executed shortly before for the Scala Regia in the Vatican. This likeness in fact had been explicitly requested by Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the king’s finance minister.

In 1675, at the age of seventy-seven, the now elderly Bernini created one of his last sculptures: theEcstasy of Blessed Ludovica Albertoni, kept in Rome in the Church of San Francesco a Ripa. This theme was not new to him; twenty-five years earlier, he had created the Transverberation of St. Teresa of Avila for the Corner Chapel in Santa Maria della Vittoria. To honor Blessed Ludovica, the Altieri family commissioned Bernini to create an altar dedicated to her. Despite the limited space of the chapel in which the altar is located, the artist was able to optimize the work by adapting the statue to the space. Ludovica Albertoni is depicted lying on an embroidered marble bed in ecstasy, the central theme of the entire composition, similar to what was done for St. Theresa. The blessed woman’s robes are more linear than those of St. Theresa, but equally striking. Bernini carefully studied the space and managed to move the wall to the back, creating two small vertical windows hidden at the sides that look outward, allowing for grazing lighting for the statue. The changing lighting during the day brings out the brightness of the work, making it more visible in the half-light of the chapel. Unfortunately, today one of the windows is bricked up and the original light has been lost. In the scene also, nine angel heads appear without wings, performing the function of a privileged audience, similar to the characters in the Corner Chapel on their boxes. In the work, the angels are close to the mystical and sensual mystery of ecstasy, creating a transcendental atmosphere.

The bust depicting the Savior, begun by Bernini in 1679 was left at his death as an inheritance to Queen Christina of Sweden and then to Pope Innocent XI Odescalchi. The Odescalchi family kept the work until the late 18th century, when its traces were lost. For the past 30 years, scholars have been trying to track down Bernini’s lost original. In 1972, the bust now housed in the Chrysler Museum in Norfolk, Virginia, was first identified; later the bust in the Cathedral of Sées, Normandy, was proposed as the original. Although of higher quality than the Chrysler Museum version, the type of marble and stylistic characteristics of the Savior of Sées suggest an author of French origin who reinterpreted the model created by Bernini in a classical key. It was not until 2001, during research for the exhibition on Pope Albani and the arts, that the presence of a bust of the Savior was reported in the convent adjacent to the Basilica of St. Sebastian Outside the Walls in Rome, hitherto unknown to scholars. The sculpture shows the Baroque stylistic traits typical of Bernini’s late production and fully corresponds to the ancient descriptions, both in the colossal half-figure size of the natural and in the pedestal material, made of jasper from Sicily.

|

| Rome, the route to discover ten of Gian Lorenzo Bernini's most famous works |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.