Looking at Prato Cathedral, whose elegant white and green marble banded facade dominates the city’s main square, one cannot help but notice the highly original pulpit that adorns the corner between the facade and the right flank, the one facing Via Mazzoni. This particular work of art, which is due to the inspiration of Donatello and Michelozzo, and which will need to be discussed in more detail in a further article, was made between 1428 and 1438, and its function was to welcome the priest during a very specific occasion: the ostension of the relic of the Sacred Girdle, which is now preserved inside the cathedral.

|

| The DUomo of Prato |

This would be precisely that belt (for those who, of course, want to believe the myth) that we have seen depicted in countless works of art depicting the so-called Madonna of the Girdle, an iconography in which the Virgin gives her own belt to St. Thomas. An apocrypha, the Transitus Mariae of Pseudo-Joseph of Arimathea, which we had discussed in the post devoted to the Contrari Chapel in Vignola, recounts that the saint, remembered for his proverbial disbelief that led him to doubt Christ’s resurrection, had not, like the other apostles, witnessed either Mary’s burial or her assumption into heaven: consequently, when the other apostles told him of the miraculous event that had raised the Virgin to heaven, Thomas did not want to give them any credit. He would then be transported to the Mount of Olives: there, Our Lady would appear to him and give him her belt as proof of the Assumption. In turn, St. Thomas would entrust the relic to a priest in exchange for a promise: the girdle was to be handed down from generation to generation.

Nothing more was to be heard of the girdle for centuries: myth has it that the tradition began again in the 12th century when, in Jerusalem, a citizen of Prato, Michael (according to some variants of the legend a member of the Dagomari family, perhaps a merchant), married a local girl, a certain Mary, who brought him the sacred relic as a dowry, received from her parents. The merchant took it with him when he returned to Prato, and jealously preserved it inside a chest on which he used to sleep: legend has it that two angels, every night, lifted him in his sleep so that he would not sleep above his waist. Around 1172 Michele Dagomari, shortly before his death, wanted to make a gift of the girdle to the proposer of the parish church of Santo Stefano (i.e., Prato Cathedral), a certain Uberto. The whole story of Michele da Prato (a character almost certainly invented) is moreover narrated in a predella painted by Bernardo Daddi roughly between 1337 and 1338, now kept at the Museo Civico di Palazzo Pretorio in Prato: this is what remains in the city of a dismembered polyptych originally kept at Prato Cathedral.

|

| Scenes from the predella with the Stories of the Girdle by Bernardo Daddi (c. 1337-1338; Prato, Museo Civico di Palazzo Pretorio): left, Michele Dagomari marries Maria; right, Michele Dagomari’s mother-in-law hands him the Sacred Girdle. |

|

| Scenes from the predella with Bernardo Daddi’s Stories of the G irdle (c. 1337-1338; Prato, Museo Civico di Palazzo Pretorio): left, angels raise Michele Dagomari; right, Michele Dagomari delivers the Sacred Girdle to the proposed Saint Stephen. |

|

| Giovanni Pisano, Madonna and Child (first decade of the 14th century; Prato, Cathedral). Photo credit. |

In 1312 a thief, Giovanni di Landetto known as Musciattino, attempted to steal the girdle: the episode had a tragic ending for the unfortunate man (who was sentenced to death), and it also had the effect of suggesting to the Prato authorities the idea of keeping the relic in a safer place: it was first hypothesized to place it in the transept whose construction work began around the middle of the 14th century, but in the 1380s of the same century it was resolved to place it inside a chapel that was to be built from scratch near the entrance portal to the cathedral. The chapel was finished in 1390 and was decorated between 1392 and 1395 with a cycle of frescoes by Agnolo Gaddi that tell the story of the Virgin and that of the Cintola: it is in this chapel, designed by the Florentine architect Lorenzo di Filippo, that the relic, which was moved here on April 4, 1395, is still kept today. Giovanni Pisano’s statue was also moved inside the chapel (a plaster copy of which is also preserved in a room of the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Prato).

|

| The Chapel of the Sacred Girdle in the Cathedral of Prato |

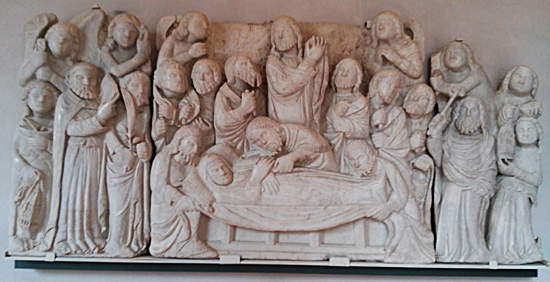

Meanwhile, the problem arose of where to display the girdle during public expositions, which until the mid-14th century took place under a wooden portico in the vicinity of the cathedral bell tower. In 1357 a Sienese sculptor, Niccolò di Cecco del Mercia, was commissioned to work on a pulpit that was finished in 1360 and then placed on the right side of the cathedral. Niccolò del Mercia’s pulpit fulfilled its function for about seventy years, when it was decided to make a new pulpit, the one made by Donatello and Michelozzo and surmounted by the characteristic umbrella canopy that makes it immediately recognizable. The reliefs that decorated it are now all kept in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo: those we observe in the square are copies. And inside the same museum we can also observe the panels of the pulpit by Niccolò del Mercia, which tell the story of the girdle. The two main panels depict the Virgin’s Transit, with the Madonna arranged on the bed, in the center of the composition, surrounded by the apostles, and the Gift of the Girdle to St. Thomas, who receives the relic directly from the hands of the Virgin, who appeared in a mandorla carried to heaven by angels. The two side panels, on the other hand, depict theCoronation of the Virgin and St. Thomas entrusting the girdle to the priest.

|

| Niccolò di Cecco del Mercia, Transit of the Virgin (1357-1360; Prato, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo) |

|

| Niccolò di Cecco del Mercia, Gift of the Holy Girdle (1357-1360; Prato, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo) |

|

| Niccolò di Cecco del Mercia, Coronation of the Virgin, left, and St. Thomas Handing the Girdle to the Priest, right (1357-1360; Prato, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo) |

Solemnity and calmness are the two main characteristics of Niccolò del Mercia’s reliefs. In the scene of the Transit, we do not see motions of desperate grief cross the faces of the apostles: many watch the scene without letting their feelings show, while others pray or turn their eyes to heaven. Almost Byzantine stylings, on the other hand, connote the scene of the gift of the girdle, with the seraphim carrying the almond and the musician angels on either side arranging themselves symmetrically, making St. Thomas himself share in that symmetry. Despite the rather crudely realized volumes and the proportions of the bodies that are often far from harmonious, however, there is no lack of certain details treated with greater care: examples are the decoration of the Virgin’s pillow, or the curls of the characters’ beards worked with the drill, or even the typically Gothic semi-circular draperies.

|

| Niccolò di Cecco del Mercia, detail of the Transit of the Virgin (left) and the Gift of the Girdle (right) |

For the preservation of the girdle, in 1448 Maso di Bartolomeo made a fine reliquary, the Capsella della Sacra Cintola: it is a masterpiece of Renaissance goldsmithing in gilded copper on a wooden core of clear classical inspiration. In fact, the shape recalls that of an ancient sarcophagus, and classical is also the decoration with ivory putti, which in turn recall those designed by Donatello for the cathedral’s external pulpit. The precious casket is now kept inside the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, since in 1638 it was planned to replace it with a rock crystal reliquary with silver and gold decorations, designed in such a way as to allow the relic to be displayed to the public without taking it out of its case and thus without the need to touch it directly. The 17th-century reliquary housed the girdle until 2008, when, for conservation reasons, it was replaced with a new gold and crystal urn made by goldsmith Giampaolo Babetto.

|

| Maso di Bartolomeo, Chapel of the Holy Girdle (1448; Prato, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo) |

|

| Easter 2007: Bishop of Prato Gastone Simoni shows the Sacred Girdle in the 1638 Reliquary. Photo credit |

|

| The 2008 Reliquary (photo from the Prato City Council website. |

Even today, the display of the Sacred Girdle represents one of the central moments of Prato’s religiosity: believers gather in Piazza del Duomo to watch the bishop display the relic from the pulpit. The event takes place five times a year: at Christmas, at Easter, on May 1, on August 15, and on September 8, the day of the Nativity of the Virgin, on the occasion of the feast day of the city of Prato, during which the ostension is the highlight of the event. On all other days of the year, it is possible to trace the history of the girdle through the works of art preserved in the city. It will be up to the religiosity (and perhaps common sense) of each person to believe or not to believe in the thaumaturgic power of this very simple strip of goat’s wool brocaded in gold threads: but it is certain that for centuries the girdle has represented a tradition on which the identity, even the cultural identity, of a beautiful and industrious city like Prato has been founded.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.