From the finds that have come down to us, we understand how Etruscan women must have cared a great deal about body care and beauty. The archaeological evidence found in the lands of Siena and displayed in the museums that are part of the Sienese Museums Foundation still tells us about the sophistication of the clothing, jewelry and precious objects with which Etruscan women loved to surround themselves.

The collections in the museums of the Sienese Museums Foundation testify to how much they loved to dress in fine clothes, wear fine andprecious jewelry , and comb their hair in elaborate hairstyles. For this, Etruscan women possessed mirrors, unguentaries, and objects of various kinds, cleverly used to make themselves beautiful for the many mundane events in society, such as shows and sports competitions.

Indeed, the Etruscan woman was gentle, refined, elegant, polite in manner and a lover of worldly pleasures. She also enjoyed a freedom often unknown to women in other ancient societies, which is well attested in historical sources. In Etruria the existence of... beauty institutes: we also know that women shaved themselves using depilatory creams and tweezers, many similar to those of today, and that they cleansed their skin with balms and ointments. In the Etruscan women’s trousseau, they also could not lack nail clippers, combs, often decorated, scented oils, mirrors-strictly made of bronze and decorated with mythological scenes and inscriptions-and, finally, makeup, made from products of plant origin. Fashions in make-up included light and sober makeup, obtained with cosmetics close to those of today: foundation, powder, blush, eye shadow, a black line for the eyes and, finally, lipstick. Perfumes, on the other hand, were obtained from plants, flowers and fruits, especially bergamot, lavender, mint and almonds.

The use of perfumed oils is documented in Etruria as far back as the 7th century B.C., as small, precious vessels for storing oils and ointments have been found in princely tombs. These were preparations composed of a fatty base, made fragrant by the addition of spices, flowers and plants, among which spikenard, cardamom, marjoram, lily, rose, laurel and myrtle stood out. Finally, fixatives such as resins and honey were added to ensure preservation.

Perfumes and vessels were placed in tombs to make up grave goods: it was believed, in fact, that they would be useful in the afterlife of the deceased and, in addition, served as indicators of the family’s economic well-being. In the Museo Archeologico del Chianti Senese in Castellina, one of the jewels of the Fondazione Musei Senesi network, several Etruscan-Corinthian unguentari from the necropolis of Poggino di Fonterutoli, dating from the late seventh to sixth centuries B.C., are precisely preserved.

Among the toilet accessories, the mirror and comb were fundamental: the former, often a nuptial gift for maidens and a funerary trousseau, was round and generally made of bronze, although there are splendid examples in silver. The reflective face of the mirror is convex-so it gave a reduced image compared to the real one-while on the other, slightly concave, mythological scenes or those related to everyday life, such as maidens in the act of combing their hair or making themselves beautiful, were engraved. One example is the splendid bronze mirror with depictions of mythological scenes preserved at the Civic Archaeological and Collegiate Museum of Casole d’Elsa, one of the most fascinating pieces in the collections of the Sienese Museums Foundation.

The comb testifies to Etruscan women’s great passion for elaborate and sophisticated hairstyles. Among the museums in the Siena lands we have an exceptional ivory specimen decorated with winged lions, preserved at the Museo Civico Archeologico e d’Arte Sacra Palazzo Corboli in Asciano. Etruscan women used to soften their hair with oils and pomades imported from the East: the hair was then braided, or allowed to fall in long ringlets over the shoulders or gathered in a crown above the nape of the neck and secured with netting, bonnets and diadems.

Among the most refined and precious accessories, however, we find jewelry. An essential element, regarded as an ornament as valuable as modern gold brooches, was the fibula. The object was useful over time for studies of costume, social status, the level of skill attained by ancient craftsmen, raw materials, and the creative process itself. Some of the most beautiful and sophisticated fibulae are on display in the Etruscan Archaeological Museum in Murlo: a rare and valuable collection that tells the salient aspects of Etruscan daily life.

A masterpiece of Etruscangoldsmithing is the gold necklace from the Necropolis of the Pianacce (second half of the 4th century B.C.) that can be admired at the Sarteano Archaeological Museum, also part of the Fondazione Musei Senesi. Belonging to a wealthy lady, the necklace was composed of small parts: eight palmettes, six lotus blossoms, sixty-five half-spheres with a through-hole, eleven rectangular wire clips, and a large central bulla with concentric grooves. The jewelry was made using the embossing technique: the decoration was made on the thin sheet with chisels of different shapes and sizes, working the reverse side of the piece lying on a non-rigid surface. The craftsman would execute the object in the negative, drawing concavities and decorative motifs that would then be in relief when the work was finished. The details of the design were then obtained by working the front side of the piece, profiling the design with more minute chisels until greater definition was achieved.

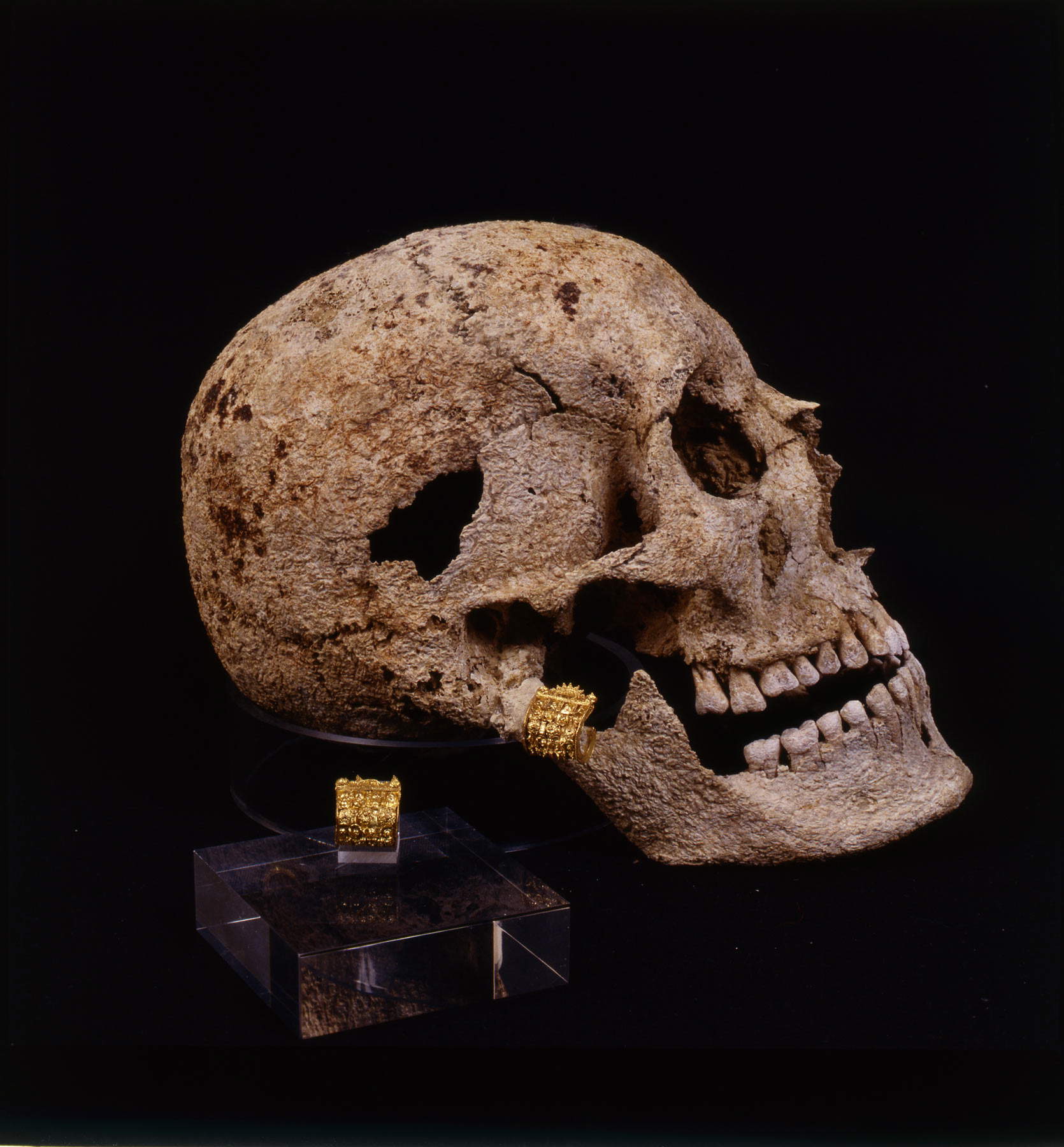

Our journey through the archaeological museums of the Lands of Siena concludes with the Archaeological Museum of Colle Val d’Elsa. Here a particular type of earrings, called “bauletto” earrings, is preserved: particularly widespread in the 6th century B.C., they were made of a curved rectangular sheet decorated with filigree, to be tied to the earlobe with a thin wire. These earrings belonged to the Porciglia Girl, named after the site of the burial discovery - at Le Porciglia, between the necropolis of Le Ville and the Etruscan settlement of Poggio di Caio.

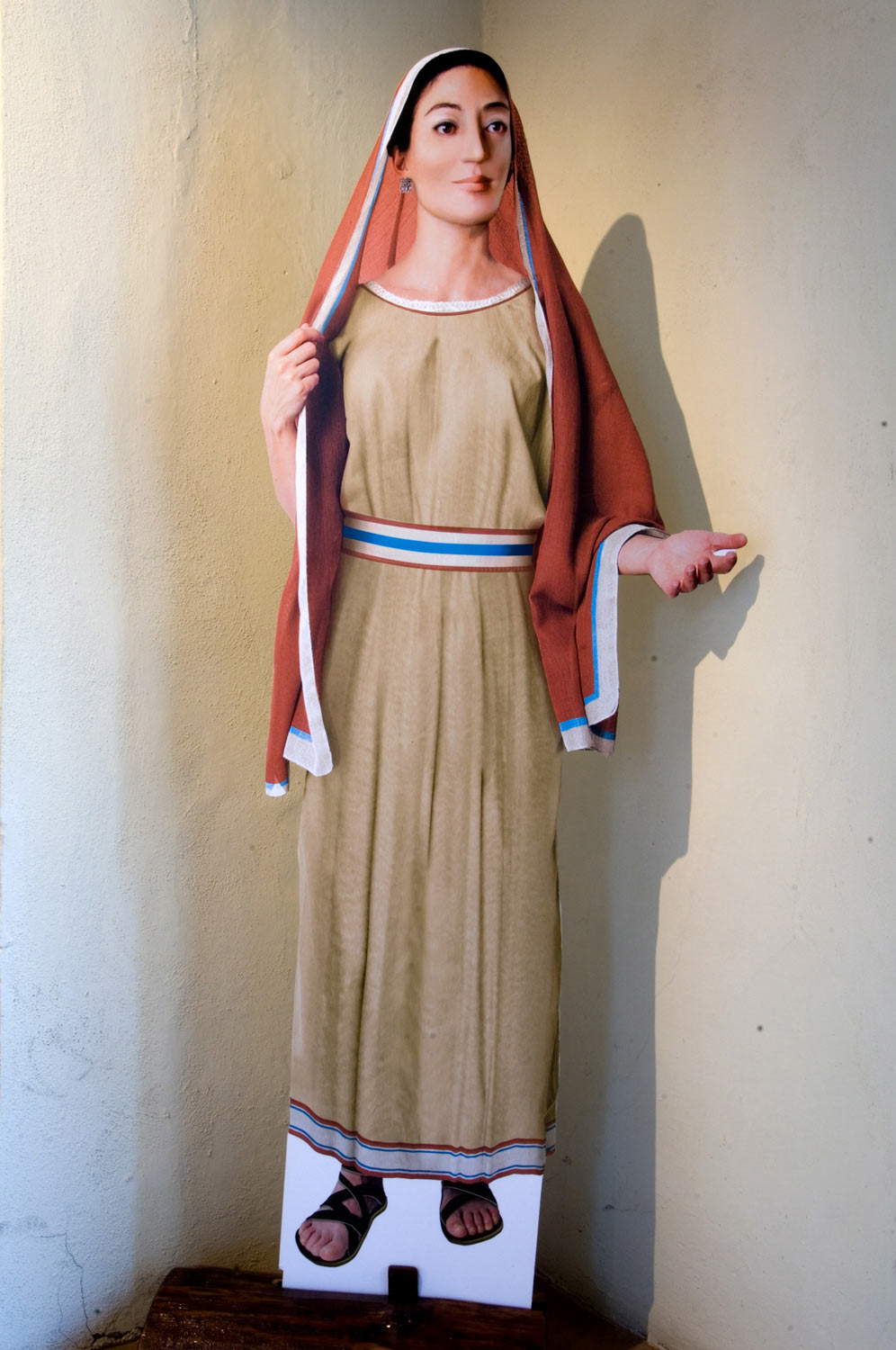

At the time of the excavation in 1996, the right earring had retained its original position and was still attached to the skull bones due to the calcification process. The archaeological discovery sparked the desire to give a face to the young woman who still wore her earrings: on the initiative of the Colligiano Archaeological Group, two groups of anthropologists were able to reconstruct, using the most modern techniques, the physiognomy of the young woman’s face, restoring to the observer the probable appearance of the maiden. The physiognomy obtained has about a 90 percent probability of matching the one the subject had in life.

To learn more interesting facts about life in the Etruscan world and to discover the riches and stories found in the lands of Siena, you can visit the museums of Fondazione Musei Senesi with a single ticket. The FMS Card is the easiest and most convenient way to discover Siena’s museums: it is valid 365 days and gives free or subsidized access, discounts at bookshops, dedicated gadgets and many other benefits. A unique opportunity to fully experience the past and present of the Lands of Siena.

|

| Perfumes, mirrors and jewelry: the beauty of the Etruscan woman in Siena's museums |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.