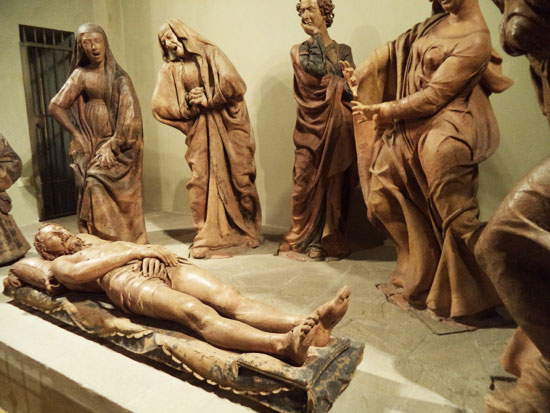

Niccolò dell'Arca's Lamentation over the Dead Christ and its violent drama.

The Marys around seem enraged with grief-Furious grief. One toward the head - on the left - holds out her open hand as if not to see the face of the corpse, and the cry and weeping and sobbing contract her face, wrinkle her forehead, her chin, her throat. The other with hands woven together, cubits out, cloaked weeps in despair. The other holds her hands on her thighs with her belly in and howls. It was on September 19, 1906, when Gabriele D’Annunzio paid a visit to the church of Santa Maria della Vita in Bologna and, when confronted with Niccolò dell’Arca’s Lamentation over the Dead Christ, he became so fascinated by the sculptures in front of him that he quoted the above phrases in his Taccuini.

A work charged with that very high dramatic intensity that is specific to much Bolognese art (and it is precisely on this expressive and dramatic line that the research of a great scholar, Francesco Arcangeli, will focus: we will discuss it at greater length in a future post), long despised by critics both because it is a work in terracotta and therefore considered less noble than a work in marble, and because it is considered grotesque for the expressions of the characters, the Lamentation over the Dead Christ has experienced, in recent years, considerable success even among the general public. And this is in spite of the fact that the name of Niccolò dell’Arca, a painter of Apulian origin who was active in Bologna for a long time, is certainly not one of the best known to the public: however, it is not uncommon to see, in Bologna, several people who, from Piazza Maggiore, take the picturesque Via Clavature, one of the most beautiful and evocative streets in the historic center, to stop in front of the late Baroque facade of the church of Santa Maria della Vita and then enter and be transported by this incredible masterpiece. An incredible masterpiece that cannot be missed in the itinerary of a traveler visiting Bologna.

|

| The Lamentation over the Dead Christ by Niccolò dell’Arca. |

To see it, we must reach the chapel to the right of the main altar. There, separated from us through an iron gate, which does not, however, prevent us from a full view of the masterpiece, we can see the terracotta sculptures made by Niccolò dell’Arca. In the center lies, now lifeless, the body of Jesus: not an Apollonian Jesus like the one to which the early Renaissance accustomed us (the dating of the work is not certain, but let us remember that Niccolò dell’Arca settled in Bologna in the 1560s), but rather a Christ extremely tried by the suffering he has endured, thin, wispy, with his mouth half-closed, making us feel a mixture of compassion for his condition and disgust at what he has undergone, and that has reduced him in this way. Next to him, on the left, kneeling, is a gentleman dressed in Renaissance garb, looking at us with a wrinkled, almost haughty gaze, perhaps to invite us to reflect: he holds a hammer and wears a pair of tongs on his belt, and these tools identify him as Nicodemus, the Jew who, together with Joseph of Arimathea, took Jesus off the cross.

In the center, the only man standing, is St. John: he tries not to be overcome by grief, he tries to maintain a demeanor, but this attempt of his cannot, however, prevent him from weeping bitterly as he gazes at the lifeless body of his master. It is in the women, however, that the depiction of grief reaches its climax. Mary, we see on the right of St. John, leans her body forward, holds her hands together, and lets her face be overcome by a grimace of acute grief, the desperate pain of a mother who has just lost her child. On the far right we have the figure of Mary Magdalene, running toward Jesus, almost as if the news of his disappearance has just reached her. Her robe is lifted by the wind, a couple of centuries ahead of the works of the Baroque and Gian Lorenzo Bernini, and she, too, is in the grip of despair: she is a real, natural woman who cannot hide what she is feeling. And the same is true of the other two women, Mary Salome and Mary of Cleophas: the first, the one next to Nicodemus, assumes a disheveled pose, and in order not to succumb to heartbreak and therefore not to fall, she has to rest her hands on her knees almost to support herself, while on the face of the other one we can read a motion of horror, confirmed by the fact that she brings her hands in front of her face, as if shielding herself from what is in front of her.

|

| Magdalene’s despair |

Niccolo dell’Arca knows no filter. His flair consists in the fact that he offers us a Lamentation as no one had dared to represent it until then: without the slightest composure, almost without decorum we might say, with these faces disfigured by pain. So disfigured that Niccolò dell’Arca’s Marys have become proverbial in Bologna: of an unattractive, uncouth and unkempt woman it is said that she “looks like a Mary of Life.” This is enough to testify on the one hand to the charge of extraordinary pathos, hitherto unknown, that this Apulian sculptor infused into his sculptures (which, moreover, still preserve traces of their original polychromy), and on the other hand to the misfortune that for a long time characterized the Lamentation. Misfortune that also caused us to lose several pieces of information about the work, beginning with the fact that we know neither for whom it was made nor exactly when. One of the greatest art history scholars of the last century, Cesare Gnudi, following the discovery of some documents, hypothesized 1463 as the date of its realization, although he shifted the execution of the last two figures, those of Mary of Cleophas and Mary Magdalene, to the 1480s for stylistic reasons: this is the most widely accepted dating. We do not even know what the exact arrangement of the statues was, because over the centuries the work underwent numerous displacements: the arrangement we see now is the result of a reconstruction made by another scholar, Alfonso Rubbiani, and dating from 1922.

But where does the great force that depicts these prominent Marys so endlessly weeping, as Carlo Cesare Malvasia had called them in 1686, come from? Much of this expressive charge is due to the typicality ofBolognese art: anticlassicism and spontaneity have always been typical features of most of the works produced in Bologna. But Niccolò dell’Arca, being from Apulia (in fact, in many documents he is mentioned as Niccolò d’Apulia: the name by which he is most famous derives from his most famous work, theark of San Domenico), probably had well in mind the violent weeping of the prefiche, women who since ancient Roman times were paid to mourn at funerals, and gave themselves up to blatant laments and theatrical displays of grief: a custom that was practiced for centuries in many parts ofsouthern Italy. The fiery dynamism of the figures could also be explained by the sculptor’s good knowledge of the art of the Ferrarese school and its artists, such as Cosmè Tura, as well as the art of Donatello: all artists devoted to an art of strong emotional impact.

|

| Another view of Niccolò dell’Arca’s Lamentation over the Dead Christ. |

What is certain is that this work exerts considerable fascination on the viewer. And probably this fascination would have been even greater if the original polychromy of the terracotta had been preserved. Terracotta that is the material par excellence of Emilian sculpture: think for example of Guido Mazzoni or Antonio Begarelli. Fascination and remarkable emotional transport: a transport that can be read well on the faces of the visitors who enter Santa Maria della Vita every day to observe Niccolò dell’Arca’s masterpiece. Its power lies, after all, also in this: managing to so powerfully engage the onlookers almost six hundred years after its creation. Only a great artist succeeds not only in passing on its memory in a most vivid way, but also in moving people even today as it did then.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.