Driving along the Pisan waterfront in Calambrone, that is, the last hamlet of Pisa before entering the municipal territory of Livorno, it is not uncommon to come across some recurring presences: the seaside colonies, which represent a fundamental chapter in the social and architectural history, not only in Pisa, of the 20th century. These complexes, built mainly to house children during the summer months, are still perhaps the most cumbersome witnesses of the social housing of the fascist regime: in fact, all the colonies in Calambrone date back to the 1930s. However, the idea of seaside colonies originated at the end of the 19th century: initially promoted by doctors and philanthropists, these facilities were intended to provide a healthy environment for children from the less affluent classes, fostering their well-being through exposure to sea air, outdoor activities and healthy food. In time, the idea found fertile ground in Italy, where the long and varied coastline offered numerous opportunities for the construction of sea colonies.

The first sea colonies in Italy were built in the late 19th century, but it was not until the Fascist period that their numbers grew significantly. The regime saw the colonies not only as a means of offering children from the less affluent classes the opportunity for a seaside vacation, but also, and perhaps above all, as a means of training future Fascist citizens, as well as spreading its ideology through sports and educational activities. During this period, the seaside colonies became not only places for summer stays, but authentic centers of physical and moral education. And the waterfront of Pisa, particularly with Calambrone, became one of the main centers for sea colonies during the Fascist twenty-year period. The geographical location, with its wide beaches and favorable climate, was ideal for this type of facility. Thus it was that, between the 1920s and 1930s, the regime initiated an intense urbanization of the Pisan coastline, first by founding two new centers, namely Tirrenia (which remains one of the main founding towns of the regime: today it is a fraction of the municipality of Pisa), and Calambrone itself, which borrowed its name from the one that was always used to identify the stretch of coastline between Pisa and the port of Livorno. And once the two centers were founded, numerous colonies were built, financed by public and private entities as well as large Italian companies.

Even today, the seaside colonies on the Pisan waterfront are the most noticeable presences on the Calambrone coast, imposing buildings in the rationalist style that often intended to echo the architecture of ancient Rome, but at other times built instead according to more eclectic schemes. They were all built in the vicinity of the beach. The first to be completed, in order of time, was the Colonia Firenze, built between 1931 and 1932 and designed by Ugo Giovannozzi: it was the colony of the Gioventù Italiana del Littorio and was characterized by a pavilion structure, which could be used individually. It is located on the waterfront and is distinguished by its light rationalist architecture of metaphysical inspiration: loggias, curved elements along all the blocks that follow one another along the waterfront predominate. It is, moreover, the only colony in Calambrone that is still in a state of abandonment.

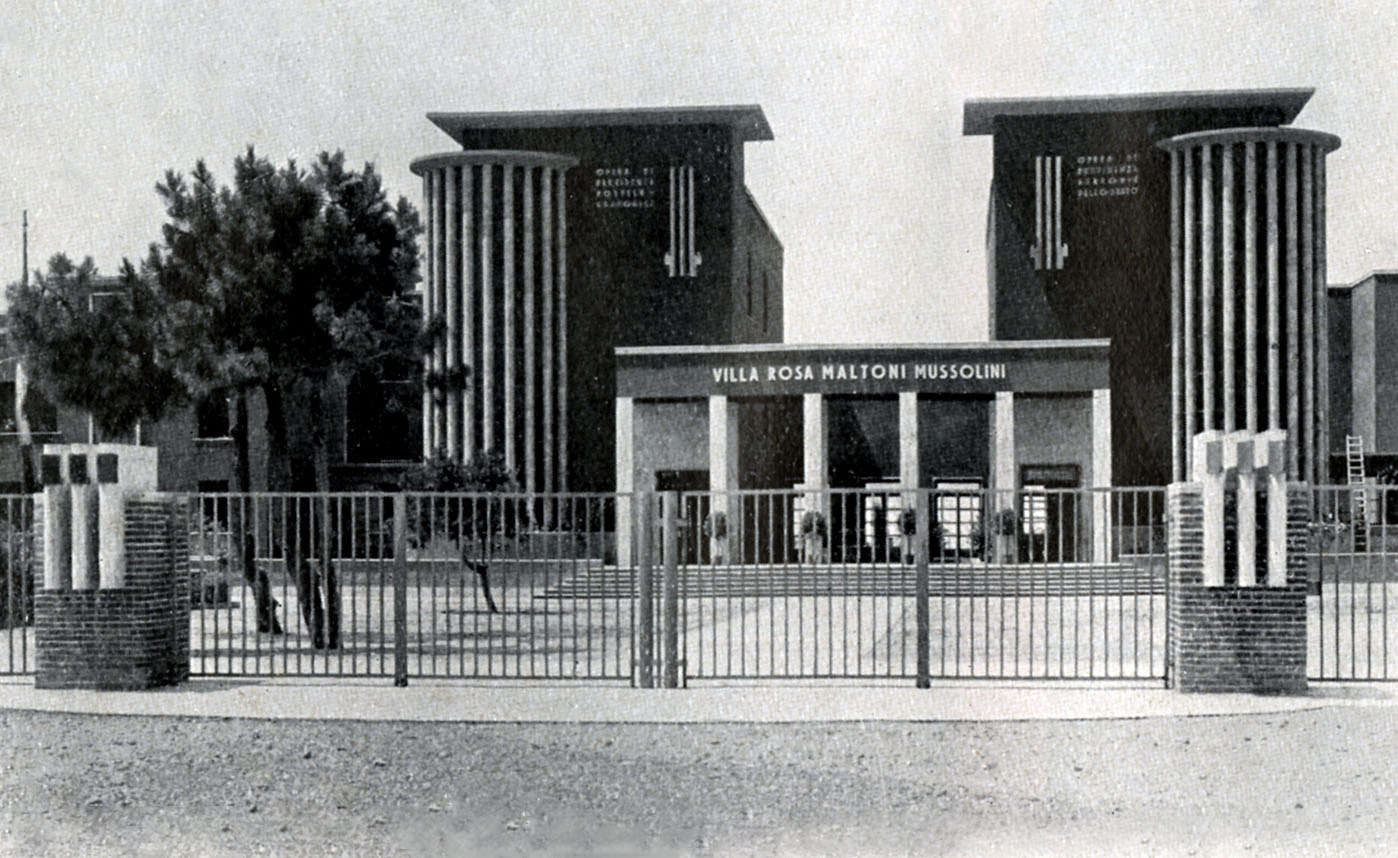

By contrast, the Colonia Rosa Maltoni Mussolini, named after the Duce’s mother, was commissioned earlier (between 1925 and 1926) but completed later (in 1931, although the inauguration dates back to July 14, 1933), the largest of the Calambrone colonies, designed by engineer Angiolo Mazzoni Del Grande. The complex integrated not only a colony (intended for the children of railroad and postal workers), but also a boarding school, library and chapel, and gave directly onto the beach: the large complex was preceded by a portico with two small buildings on the sides that acted as propylaeums and led into the two bodies of the complex (the southern one for the postelegraphers and the northern one for the railroaders), The architectures recalled those of futurism but also those of metaphysics, given also the presence of two tall cylindrical towers that contributed to characterize theidentity of the complex, which also stood out from the outside because of the red color with which the surfaces were coated.

Another notable example is the Colonia Principi di Piemonte. Built between 1932 and 1934, this colony was intended for the children of Air Force personnel. The structure, rationalist but inspired by neoclassical architecture (a unique example in all Pisan sea colonies), is characterized by two parallel blocks, joined by an enclosed portico, whose shape vaguely resembles that of an airplane, symbolizing the destination of the complex.

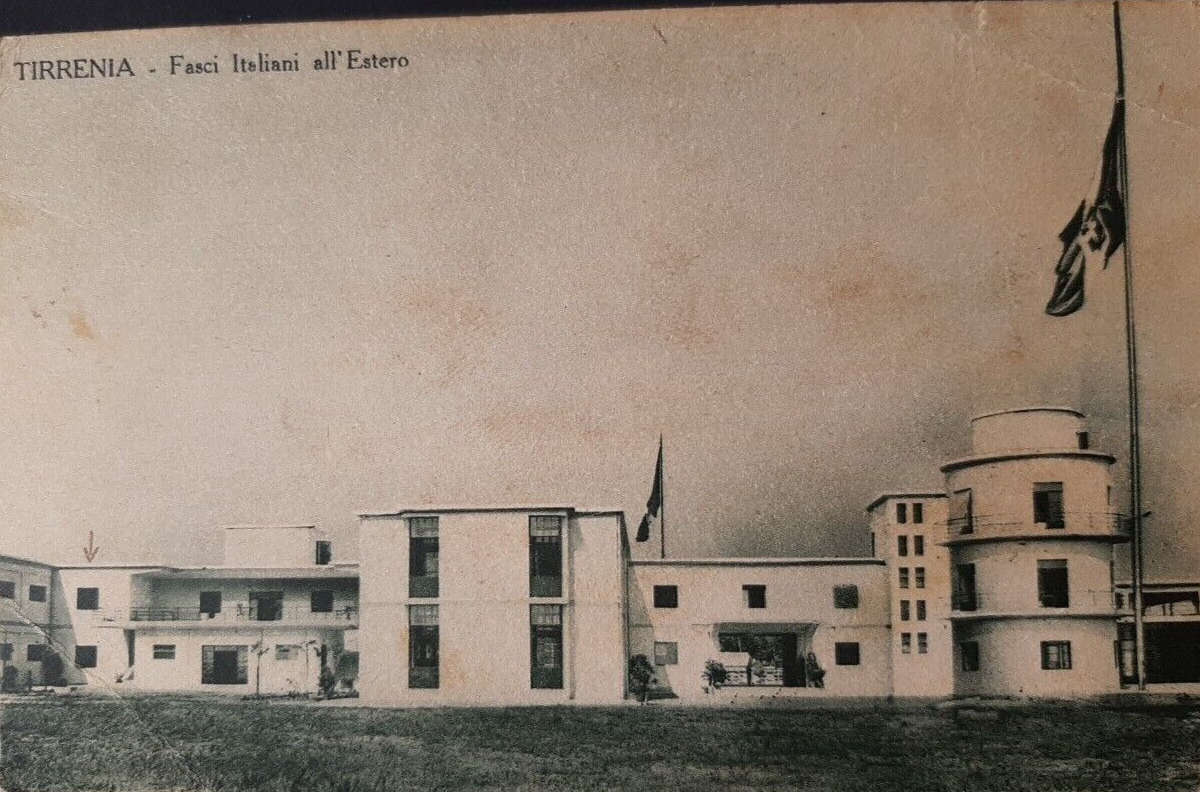

The Colonia femminile dei Fasci Italiani all’Estero was built between 1934 and 1935, which as its name suggests was the marine colony for the daughters of Italians residing outside the national borders, and was built at the behest of Piero Parini, secretary general of the Fasci Italiani all’Estero: the project was entrusted in 1933 to architects Giulio Pediconi and Mario Paniconi. Initially it was planned that the colony would house 400 girls, but later the project was expanded and eventually the complex could accommodate 1,100 girls. It too was built, like the Florence Colony, with a pavilion structure, and was praised at the time as being considered one of the architecturally most successful colonies, especially for its ability to combine sober rationalist architecture with efficient organization of space, as well as for the care taken with the interior finishes. Again, the entrance was designed as an airy open portico that led guests to the blocks of the complex.

One of the most significant examples of a seaside colony in Calambrone is then the Colonia Regina Elena, designed by Ghino Venturi, begun in 1931 and inaugurated in the summer of 1933: initially envisioned as a “heliotherapy town” connected to Livorno’s Spedali Riuniti, starting in 1937 it became a colony of the State’s Opera di Previdenza e Assistenza dei Ferrioveri, and also housed a boarding school. The complex, composed of three buildings, two of which are placed parallel to the coast and one instead arranged on the sea-mountain axis and connected to the other two bodies by a long portico, is distinguished by its rationalist style, characterized by clean geometric lines and wide open spaces.

Finally, it is worth mentioning Colonia Vittorio Emanuele II, the last in chronological order, built to a design by architect Gino Steffanon between 1934 and 1938. This structure represents another example of rationalist architecture. The colony, inaugurated in 1938, was intended for the children of workers in the textile industry and featured an imposing structure, in the shape of a semicircle with a rectilinear main façade, with rigorous and symmetrical forms: the choice of the shape, we read in documents of the time, was modeled on that of a child stretching his arms toward the sky.

After World War II, as economic and social conditions changed, many seaside colonies lost their original function. Improved living conditions and increased summer vacations for families reduced the need for these facilities. Several colonies were abandoned or converted for other uses. However, in recent decades, some of Pisa’s waterfront seaside colonies have undergone rehabilitation and reconversion projects, and today all the colonies in Calambrone, with the exception of Colonia Firenze, are living a new life. Colonia Rosa Maltoni Mussolini continued to be used as a colony until the 1960s. It then became a resort for the disabled, and was later abandoned. In the 2000s it was finally recovered and today has become a residence, the “Regina del Mare.” The Colonia Principi di Piemonte also continued to exercise its original function for a time, until the 1970s, when it was abandoned. Also redeveloped in recent times, it is now a hotel-resort that still bears its original name. The Women’s Colony of the Italian Fasciani Abroad continued to be a vacation spot for the underprivileged until 1965, after which it became a hospital, and then fell into disuse. Restored in the 2000s, it became a complex for residential use called “Villaggio Solidago.” Colonia Regina Elena was completely abandoned in 1977: restored at the beginning of the 21st century, it too was turned into a residential complex. Finally, the Colonia Vittorio Emanuele II, after years of abandonment, was the subject, starting in 2008, of a recovery project that turned it into a seaside resort with residences and a hotel.

Today, the seaside colonies on the Pisa waterfront are recognized as important examples of rationalist architecture and Italian cultural heritage. Their preservation and enhancement are a way to preserve the historical memory of an era and to appreciate the aesthetic and functional value of these buildings. They are then also a living piece of history that makes us reflect on the social policies of the past and how they affected people’s lives. Studying the sea colonies allows us to better understand the social, economic and political dynamics of the 20th century. They are therefore much more than buildings that have been transformed into vacation villages or apartments today. They represent a piece of Italian history, an example of innovative architecture and a symbol of the social policies of the past. Today, through restoration and enhancement projects, we can continue to use and visit these spaces, recognizing that they are part of our cultural heritage. With each step toward the preservation and enhancement of these historic buildings, we ensure that their memory remains alive and their importance to the community continues to be recognized.

|

| Marine colonies on the Pisan coast, from fascism to rebirth |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.