Ravenna ’s past is inextricably linked to the period when the city was part of theByzantine empire: in particular, Ravenna was for almost two centuries the capital of theExarchate of Italy, the district of the empire that controlled in territories on the Italian peninsula. So, by virtue of this important history, there are no other cities in Italy that can boast so many monuments (and, moreover, so well preserved) relating to the time when Italian history was linked to that of the Byzantine empire.

Ravenna was annexed to the empire in 540, when it was conquered by Belisarius, a general in the service of Emperor Justinian I: the city, which had already been, in the fifth century, the capital of the Western Roman Empire given its strategic position on the Adriatic Sea, and had also been the capital of the Kingdom of the Goths, was about to become an important capital again. This occurred in 584, when the Exarchate was established and Ravenna became its capital, a role it held until 751, the year of the fall of the Exarchate at the hands of the Lombards, who occupied its territory, all the way to the city: the Lombard king Astolfo thus took up residence in the exarch’s palace, sanctioning the end of the history of Byzantine Ravenna. There are many testimonies to this period of history, including some masterpieces of Byzantine art: for our Five Places in Two Days format, it is time to travel through Byzantine Ravenna with five stops for a complete immersion in an era that still characterizes part of the urban fabric of the city of Ravenna.

|

| Basilica of San Vitale. Photo Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Arian Baptistery. Photo Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Sant’Apollinare in Classe. Photo Finestre Sull’Arte. |

All that remains today of the building known as “Theodoric’s Palace” is a simple though imposing façade, which, moreover, we find perhaps also reproduced in the mosaics of the church of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo (though modified precisely in the Byzantine era, when, by damnatio memoriae, the effigies of the personages connected with Theodoric’s court were erased). We are not sure what this structure is: according to some scholars it could be the rest of a guardhouse that guarded the access to the Palace of the Exarch, the place where the highest representative of Byzantine authority in Italy exercised his power. It could, however, also be the porticoed atrium of the church of San Salvatore ad Calchi, an important house of worship in medieval Ravenna.

|

| The Palace of Theodoric. Photo José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro |

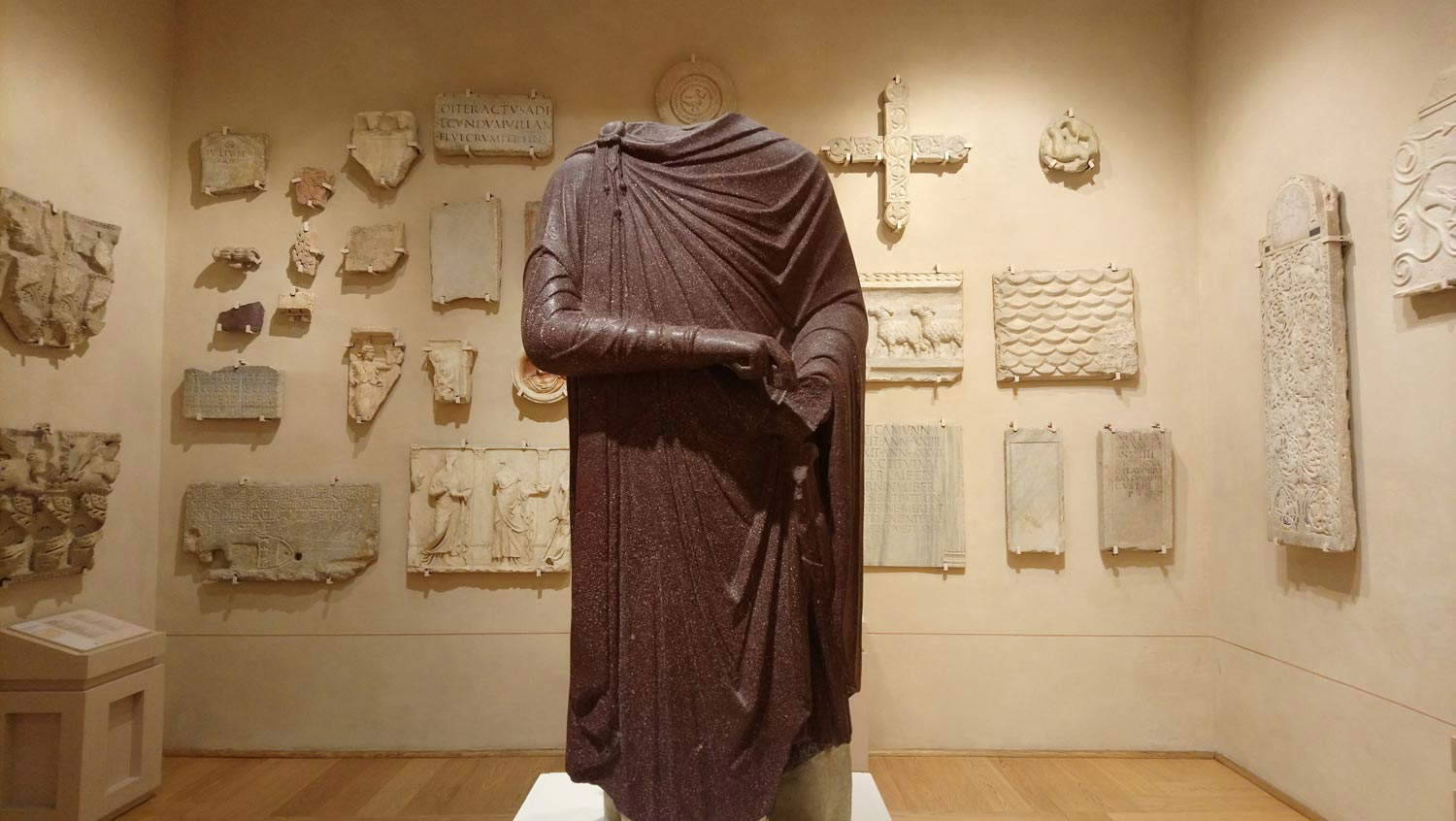

A rich lapidarium that houses sculptures from every era, including Byzantine, the collection of archaeological material, the extraordinary ivories, Byzantine coins: the National Museum of Ravenna, one of the main ones in the city and in the whole region, preserves numerous testimonies of Byzantine Ravenna, as well as having a collection that spans the centuries, up to the Six-Seventeenth century (there are also icons, made especially from the fifteenth century: in its genre it is one of the most important collections of icons in the country), ceramics, weapons and armor. It is a museum with a long history, since it originated from the collecting of the monks of Classe (the hamlet near the sea where today the brand new Classis - Museum of the City and Territory is located, another must-see place if you want to know in depth the history of the city from its origins to the present day), from which the Classense Municipal Museum originated in 1804. The current museum, thus born from this collection, was born instead in 1887 when the municipal collections were nationalized, while in 1913 it was moved to its current location, the ancient monastery of San Vitale, near the monumental complex of the basilica of the same name.

|

| The National Museum of Ravenna. Photo Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| A room of the Classis museum. Photo Finestre Sull’Arte |

The Archiepiscopal Museum of Ravenna is one of the oldest museums in Italy (it was established in 1734) and tells the long history of the Archdiocese of Ravenna, which for a long time also played a notable political role. Inside is preserved a splendid collection of works from the Byzantine era, including one of the most important masterpieces of 6th-century art, the celebrated chair of Bishop Maximian, a splendid ivory throne consisting of twenty-six panels decorated with scenes from the lives of Christ and Joseph, as well as with figures of saints and floral and plant motifs. The museum also has statues from the period, including a headless portrait possibly depicting Emperor Justinian, and then again the cross of Archbishop Lamb, remains of mosaics. Not from the Byzantine period, but a unique treasure is the Archiepiscopal Chapel of St. Andrew, which is part of the assets on the Unesco list and whose visit is integrated into the museum tour, as it is a room in the Archiepiscopal Palace: it was built in the late 5th century and is the only bishop’s chapel of the period that has come down to us.

|

| The Archiepiscopal Museum. Photo Finestre Sull’Arte |

This is a recently discovered archaeological site. It is a small Byzantine palace from the 5th-6th centuries, and it is the only private residence from that time that has survived in Ravenna. It owes its name to the mosaics that decorate its floors (they were called “stone carpets” by Federico Zeri), and to admire them it is necessary to pass through the church of St. Euphemia, where the entrance to the Domus is located. The layouts of the site have all been redone recently in order to supplement the visit with a tour that illustrates the history of the palace. There are a total of four hundred square meters of mosaics, which can be admired in their entirety, with decorations with geometric or figurative motifs (such as those with the Dance of the Genes and Seasons and the Good Shepherd).

|

| The Domus of the Stone Carpets |

|

| Journey to Byzantine Ravenna: five places to see in two days |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.