by Redazione , published on 20/11/2020

Categories: Travel

/ Disclaimer

The village of Coreglia Antelminelli in the Middle Serchio Valley is famous for two things: plaster figurines and emigration. And they are closely linked. A journey through the village that has taken the "figurines" created by its inhabitants into the world.

A scholar from Lucca, Guglielmo Lera, a profound connoisseur of the history of his land, noted in one of his articles, with a certain dose of irony, that in Coreglia Antelminelli, a village of medieval origins located on a hill in the center of the Media Valle del Serchio, they invented two things: plaster figurines and emigration. And figures and emigration are closely related, because the inhabitants of this hamlet and the villages around it have been selling plaster figurines for centuries, getting them to all corners of the world: a tradition that has been going on since at least the seventeenth century, when in Rome a certain Prudenza Zanotti received some prints for figurines from a certain Giovanni Simone Fontana, a young man who came from Tereglio, now a hamlet of Coreglia. We learn this from a document dated February 24, 1676: already at that time, then, artisans of figurines were moving around the world to take their figurines. And even, in an application addressed by the Council of the Men of Coreglia to the Most Excellent of the Republic of Lucca, on April 12, 1774, we read that “in former years because of the migration suffered by many communitarians on account of the manufacture of plaster casts, ristrinto assai was the number of subjects skilled in government.” And so the coreglini asked the Republic to make their measures valid even with a numerically smaller assembly than that provided for in the statutes-a document that gives an idea of how important, even then, the phenomenon of emigration from this valley was.

Artisans, after all, had to export their creations to survive. In ancient times they were the “stucchinari,” or “figuristi,” while from the 19th century the term “figurinai” spread, first in the journalistic and literary fields and then outside these spheres as well. And there is reason to believe that, in ancient times, virtually all the inhabitants of Coreglia were figurinai: it is said that Coreglia was once full of figurines. They could be seen everywhere around the village: in front of houses, on terraces, on street corners, in vegetable gardens. The figurinai would leave them out in the open to dry. And even today, especially on window sills, some can still be seen. But they are sporadic presences, welcoming the traveler among the steep cobblestone alleys that climb up to the town hall square, at the highest point of the village, and then open surprisingly, from the square, into a pair of wider, more airy streets, overlooked by the town’s most elegant mansions.

We do not know when or why this tradition was born in Coreglia. Perhaps it was because, after all, getting the material to make plaster figurines was not that complicated, and because the workmanship was easy. No figurines have survived that predate the eighteenth century, although we know from documents that figurines were already being made in the century before. Today, the oldest that remain to us are two eighteenth-century cats, blackened with candle smoke, preserved at the Museum of the Chalk Figurine and Emigration, opened in 1975 in the rooms of Palazzo Vanni and named after the very Guglielmo Lera who had worked so hard to open it, bringing together the history of the figurine makers in an institute dedicated to them. Cats are the oldest figures because the cat is the easiest subject to deal with in chalk (and because there are plenty of cats in Coreglia: in winter, more cats are encountered in the streets of the village than people), but for centuries production has flanked the felines with many other far more marketable motifs. Nativity figurines, for example: these are by far the most popular. Then there is the plaster statuary from houses of worship, which is apparently still going strong in South America. There are also reproductions of famous works: in the Coreglia museum one encounters the Laooconte, Desiderio da Settignano’s Saint John , Michelangelo’s Moses , Canova’sAmore e Psiche , Thorvaldsen’s Hebe . A bizarre history of sculpture, from its origins to the present, made with plaster miniatures.

|

| Through the streets of Coreglia Antelminelli. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Through the streets of Coreglia Antelminelli. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Palazzo Vanni, home of the Museum of Chalk Figurine and Emigration. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| A room of the Museum of Chalk Figurine and Emigration. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| A room of the Museum of Chalk Figurine and Emigration. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Thorvaldsen’s Hebe in plaster. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The two plaster cats blackened with candle smoke (1760). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Nineteenth-century portraits executed using the lost print technique. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Plaster crib figurines at the Museum of Plaster Figurine and Emigration. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

And then there are many portraits, another subject that made the fortune of figurine makers, especially in the 1800s. Artisans from Coreglia and the surrounding area would set out from these mountains, walk to the coast, and board the ships that would take them everywhere, especially to America. Little baggage, lots of courage and a great load of hope. Small companies were formed, market areas were divided, they would leave with the box, the display material, and sell the plaster figurines on the streets of the New World. The poor figurine makers who traveled the great cities of the United States in full struck even the imagination of Giovanni Pascoli, who lived in these parts when migration was at its peak, and who speaks of them in his poem Italy. "Buy images... for Troy, Memphis, Atlanta / with a voice that accora yourself: / cheap! In the night, alone, among so many / people: cheap , cheap! Amidst a howl that oppresses; / cheap! At last another odi, singing.... ".

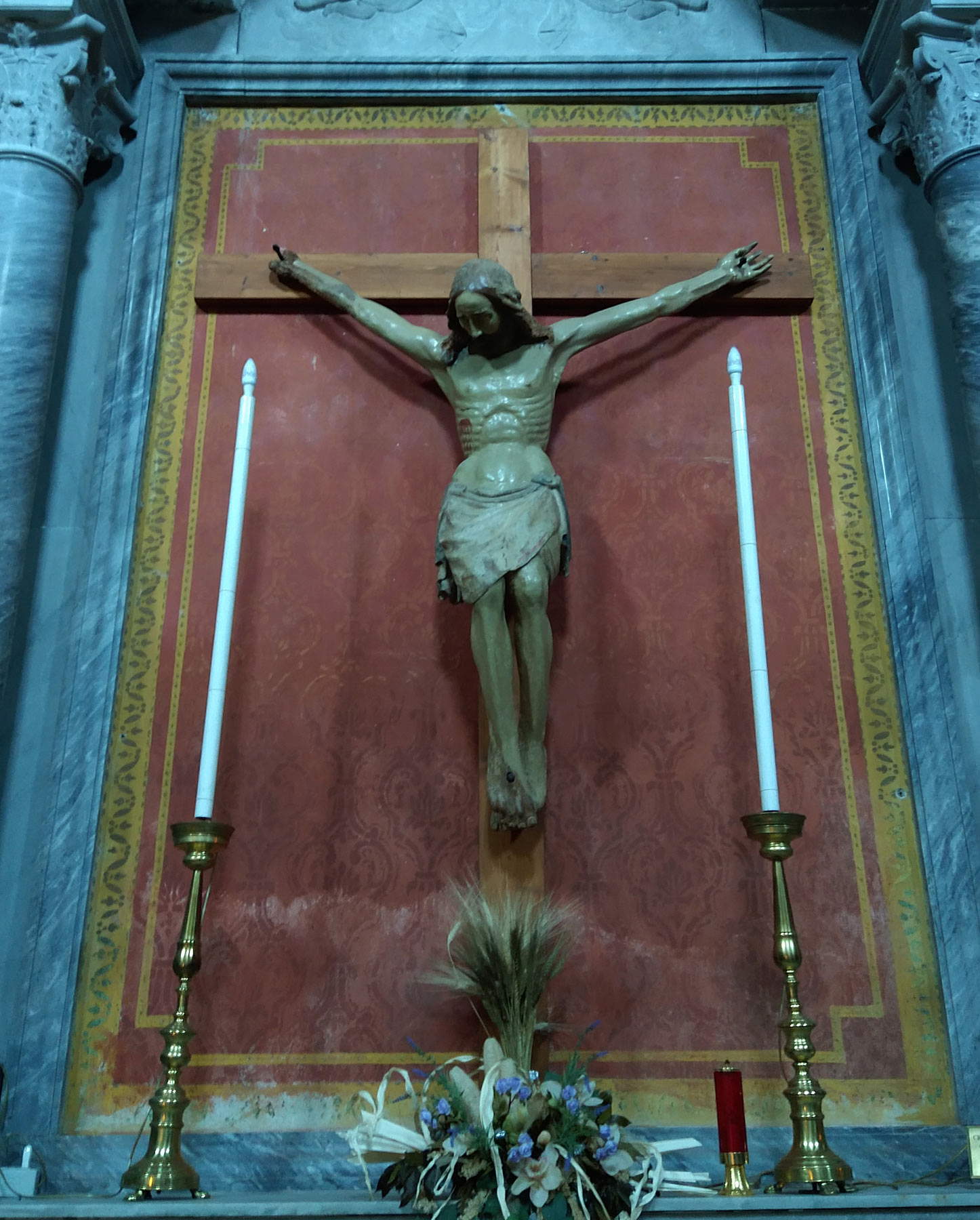

Today in Coreglia there is a statue honoring the figurine makers. It stands in the widening next to the austere church of St. Michael, dedicated to the town’s patron saint, a large 11th-century stone building whose interior was renovated between the 18th and 20th centuries. Inside is a large 16th-century marble statue of St. Michael, a 15th-century wooden crucifix, and two splendid Gothic sculptures, also in marble, depicting the Announcing Angel and the Virgin Annunciate, dated from 1351 by the scholar Marco Paoli. The church stands on one of the town’s two squares: the other is the town hall square, on which stands the elegant 16th-century facade of the Town Hall. It is not uncommon to find, in this mountain village, some tasteful palazzotti: it is true that the figurinai left poor, but some managed to make their fortunes on the other side of the ocean or beyond the Alps. There are several items in the village museum that tell these stories, and one of them is that of Carlo Vanni himself, the owner of the building that houses the institute. He, too, was a poor figurine maker of humble origins who left for the Austro-Hungarian Empire: his figurines were successful, he did some work for the imperial family, and even received the title of baron. And when he returned to Coreglia, good-hearted man that he was, he did not keep his success for himself, but wanted to share it: with his earnings he bought the palace, had it renovated, and on the main floor he set up his residence, but on the first floor he opened a kindergarten and a drawing school, which remained active until the 1950s. Young people from the village came here to learn the art of figurine making. And generations of figurine makers were formed thanks to the generosity of “Baron Vanni.”

This is one of the many stories behind the figurines of this village of stone and plaster, the ancient fiefdom of the Antelminelli family that prospered thanks to its figurine makers, who were able to undertake journeys that could last as long as three years: months and months away from home to fill the world with figurines from the Serchio Valley. Today there is only one company left that still makes the figurines: new materials such as plastic and industrial production have all but wiped out production. But Etruria Statue, for more than twenty years, has been passionately continuing Coreglia’s historic legacy, exporting plaster figurines to twenty countries. And abroad, Coreglia’s name is perhaps better known than in Italy. Every summer, throngs of tourists arrive here from all over: many are in search of their origins, because it often happened that the figurine makers did not return and settled in America, Belgium, Austria, Japan, wherever. They arrive in droves, and they wander the streets of the village, scrutinize the figurines in the Figurine Museum, hobnob with the people of Coreglia hoping to find the name of that Italian grandfather who, with the box of figurines around his neck, shouted “cheap!” through the streets of Memphis and Atlanta.

|

| The monument to the figurine maker. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| St. Michael’s church. Ph. Credit BeWeB |

|

| St. Michael’s bell tower. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Interior of the church. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The 16th-century marble statue of St. Michael. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The wooden crucifix from the 15th century. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Announcing angel (1351). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The Municipal Palace. Ph. Credit Municipality of Coreglia Antelminelli |

Article written by the editorial staff of Finestre sull’Arte for UnicoopFirenze’s “Toscana da scoprire” campaign.

|

| Coreglia, the ancient village of emigrants who brought plaster figurines to the world |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.