Caesar Brandi: en route to Palmyra

Cesare Brandi (1906 - 1988) was not only a great art historian, but he was also a curious traveler, who decided to gather his travel memoirs in several writings. What we offer below is an excerpt taken from a writing in which Cesare Brandi recounts a trip he made to Palmyra in the mid-1950s: in this case, we have selected the part of the narrative during which Brandi recounts his journey to the Syrian city and his first impressions as soon as he arrived. It is a valuable document that guides us through the desert sands of Syria and, later, through the ruins of Palmyra, as seen through the watchful eye of Cesare Brandi. His dry, simple but elegant, and strongly descriptive style almost seems to make us imagine the difficult journey, which, however, ends with a magnificent vision, that of Palmyra. The piece first appeared in the 1958 volume “Cities of the Desert”: the book was published in a new edition last year by Elliot Editions. Happy reading!

|

| Caesar Brandi |

At half past four in the morning we set off. As soon as we left Damascus, the countryside, still dark under the lofty sky, was reminiscent of the thickly wooded countryside toward Nocera dei Pagani, in Naples, when one leaves the road to Pompeii and the valley, narrowing to meet Cava dei Tirreni, regurgitates with green, overlapping three storeys, highest of all that of the walnut trees. I could see the rump of the apple trees and, below, a shaggy green. But it was short-lived and short-lived on the paved road. The driver could hardly understand a word of the languages in which I could well or poorly express myself, and fortunately he did not even attempt to turn on the radio. He was talking to the young son he had brought with him, and when I had seen him, I had felt relieved of a certain burden: because doing almost six hundred kilometers in the desert with a stranger, a Syrian to boot, in the Suez Canal period, when you never know which way the wind is going to blow, and if by chance at any moment you don’t find yourself in the midst of a pogrom on the type of the one the Turks did to the Greeks in Constantinople a few months ago, all that doesn’t exactly prepare you for a leisurely trip. The innocent presence of the son then put my mind at rest [...].

By now it was right in the desert, and it was flat, smooth almost, sprinkled with such fine crumbled gravel as to seem in the garden. The tracks were vague. At a little village of those mixed with mud, a Bedouin had mounted: without even questioning me. We had stopped, the driver had put water back in the radiator, the child had eaten a slice of watermelon. I had stood watching a woman kneading crushed straw and mud. She was young and expressionless: she had that costume, which would have been very pretty, with tight breeches of flowered pannina, and the gala at the bottom, then a shorter skirt, her head wrapped in black veils. She kneaded with gestures always the same and dry as one who makes stockings, kneading, in the manner of twenty-five thousand years ago, the same mud bricks to be dried in the sun to build the same low, long huts, which on the mountainside look, from a distance, like uneven steps. He was kneading: an older woman was alert, standing by.

By the time we resumed our journey, arguments to no end had begun between the driver and the Bedouin. Evidently the driver didn’t know the way, the Bedouin knew the way, the driver didn’t trust it, and off they went off the track, and then back and then forward. It seemed that as soon as they found a trail they were afraid of getting caught on it. Yet I was not in alarm. The desert had resumed its invigorating action, and I never felt off track. One went, and in that going lay such a strong reason for me, as to see Palmyra. Distant hills of muted colors, between blue and purple, as in the desert have the heights: a bird of the kind of a vulture, which passed beating its wings so softly that I saw them distinctly when it closed them down, like something hanging down: no life but those sparse, low bushes that seem purpose and are not. Then one began to see two white shapes in the distance and that one could not tell what they were, whether rocks or something else. At last they had agreed, or so it seemed to me, that one must head there: as they got closer, they discovered that they were huge tanks, like gas gauges. This was the pipeline that brings oil from Iraq to the Mediterranean. That such a pipeline the Arabs intended to blow up (and they did) if Nasser was not given the all-clear. Inopinently the power line also appeared and they found themselves goats and camels, which I never saw with so little to eat as there. From the pipeline a wide track opened up for a short while, far more bumpy than the bare desert, and the level, immense, undulation-free valley stretched out to some distant mountains. Suddenly I saw distant shapes like very pointed tents, I saw streaks of the most intense green. They were farms in the desert where, by drilling, water had been found and they had immediately sown cotton there, which was green and already with open wads. But the houses were like those of Jericho, like those, that is, that resemble the trulli of Apulia, and only that those cones were not one or two, but six or seven, all in a row, and they looked rather like the spools of certain old spinning mills. New were those farms, still under construction, and still in the bill were seen the raw bricks of mud and straw. The green cotton was as lush as a fanfare. Then the thinner desert resumed and, after a while, another farmstead, until they disappeared altogether. The mountains, on the other hand, drew closer, strengthened, losing the blue they found strong colors again, from orange to purple, degrading on either side, forming a pass. In the wide hollow, as we approached, a ruined tower appeared and then others, as crags dropped. They were solitary towers, unbound with walls, from one to the other we could see sharply the slope descending. They were reddish towers, as reddish was the rock of those mountains; they were the mortuary towers of Palmyra.

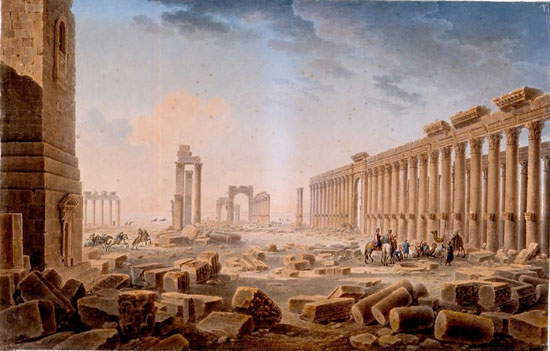

It seemed as if we were passing through a strait, and the sense as of the dried-up bottom of the sea, which arouses the desert, was accentuated. Here and there butts of towers continued, but also some tall ones almost, almost intact, of pure forms. At the bottom rose the rows of columns. But first, ahead of them all, on a pointy hill, an Arab castle, scapitozzato, sharp-edged like a crystal. The steep, almost sheer slope cut the sky. Suddenly, thickly, barely contained in an uncertain wall, an expanse of palm and olive trees, but of a green so intense that it was more blue than green.

|

| Louis-François Cassas, The Ruins of Palmyra (1821; Tours, Musée des Beaux-Arts) |

Over that restrained but violent vegetation, the sky stretched as if swollen by the wind. The absurd and extraordinary city, which enjoyed an almost inconceivable power-it reached as far as Egypt-had reappeared, a dry port of sand for the rocking ships of camels, an emporium of distant goods. The whole panorama, in its ancient perimeter, was embraced at a glance, the Temple of Bel, and the Colonnaded Way, the Agora, the Theater: everything was clear as in a model, and instead it stood before my eyes in its reality and for an extent that could not be defined, because there was no mutual measure between the mountains and the columns.

First I wanted to see the tombs: one had to walk and it was good to choose the least hot hours. This story of the tombs of Palmyra I think is almost unique in antiquity. They were, the Palmyrene, the first morticians, the first to conceive of building and selling so many tombs on top of each other; and, not content with digging them out, they built them high. This is the origin, moreover obscure, of four- or five-story mortuary tombs. Needless to say, in a city that relied entirely on commerce, there was also the speculator who bought in bulk from the builder, and then sold the burial niches to those who needed them at stranglehold. There is the record of all this, as well as of funeral banquets at which it was understood that the dead also attended: after all, it could be a convenient sideboard so as not to grieve too much.

Meanwhile, as we approached the tomb known as the Tomb of the Three Brothers, I noticed, and it had escaped my notice at first, that on that side the nature of the mountain changed, losing the red, the gnawing; rounded hills appeared that made the effect of a negative, in that they reversed the colors as one is wont to see them: a gray as of lead was on all the more prominent parts, while a soft, straw-like yellow appeared in the hollows of the ravines down to the lowest parts. It was sand, it was the famous sand I had not hitherto encountered, and which the wind accumulated in the hollow parts while sweeping away from those in prominence where the silver-colored stone remained bare. The effect, even after explained, always remained exotic to me: and then I understood why. Those mounds resembled Siamese cats; it was the same point as the yellow, and almost the same as the dark one between the lead and the charcoal. But most of all it was the same inversion that makes Siamese cats so exotic, accustomed as we are to our cats who generally have a light mask on a dark background, a light-colored tail tip, white pedals, like horses, but not all the other way around like the Siamese. So the mountains that tasted like cats were a new fascination of Palmyra.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.