by Redazione , published on 27/08/2020

Categories:

Travel

/ Disclaimer

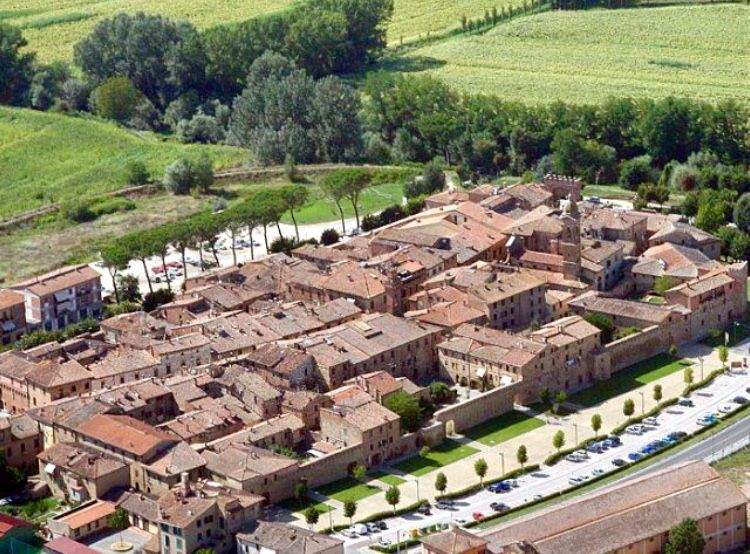

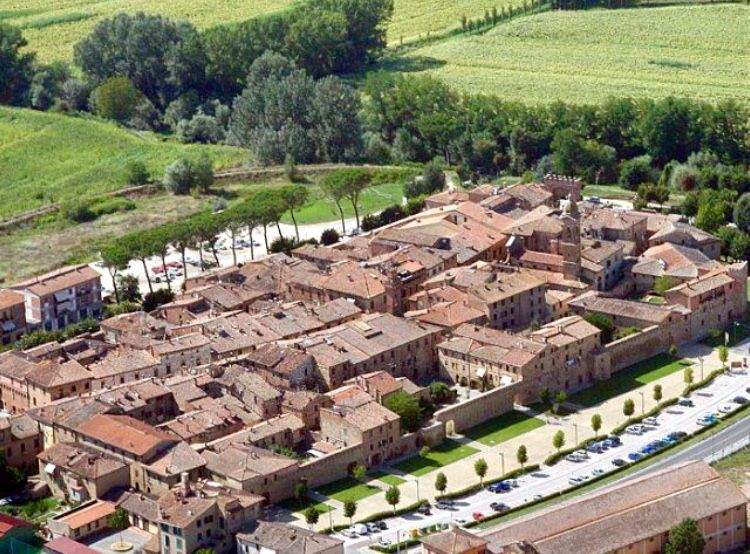

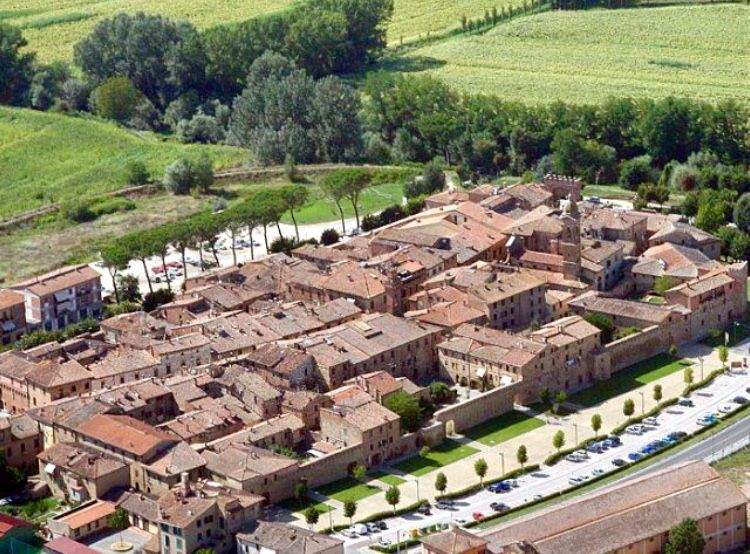

The village of Buonconvento, in the center of the Arbia valley, has a name that means 'happy place' in Latin. And indeed, visiting it confirms its etymon.

Giovanni Boccaccio tells of a certain Cecco di Fortarrigo, an avid gambler and legendary drinker, who, accompanying his dominus, Cecco Angiolieri, gambled away his own and his master’s money (savings that were needed for a six-month stay in the Marches of Ancona) in a tavern in Buonconvento, losing it all: not content with that, he pretended to have been robbed by poor Angiolieri (moreover depicted by Boccaccio in much less malicious terms than might result from reading his poems), and took away his horse and clothes. Whereupon Angiolieri, out of the shame of having been betrayed, mocked and stripped, did not dare return to Siena and repaired to his relatives in Corsignano, that is, today’s Pienza, until his father again granted him an appanage to leave for the Ancona brand.

It is difficult to find in Buonconvento today the tavern where Cecco di Fortarrigo squandered a fortune, but in the small historic center of this village nestled among the moonscapes of the Crete Senesi, it is not difficult to experience 14th-century atmospheres: here, in the shadow of the Torre dell’Orologio (a sort of miniature Mangia tower, also dating back to the 14th century), ancient brick buildings, pointed arches, the walls partly still intact and also dating back to the 14th century (although they came out devastated by World War II bombings), take the traveler back to thatepoch, when Buonconvento was one of the main centers of the Sienese Republic, strategically located in the center of the Arbia valley, and consequently experienced, in that period, a significant urban evolution, that from a simple “Bonus Conventus,” or “happy place” (and who could doubt the etymological attestation, given the amenity of the place?), became a disputed center, first occupied by the imperial army of Arrigo VII of Luxembourg, then by Uguccione della Faggiola, and then in the midst of the struggles between Perugia and Siena, with the latter getting the better of it.

|

| View of Buonconvento |

|

| The walls of Buonconvento |

|

| The Palazzo Podestarile. Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| The Crete Senesi |

Via Soccini is the main street of the village: It bears the name of one of the dynasties that most marked its history, even boasting not one but two heretics, Lelio and Fausto, one a grandson of the other, who between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries spread Socinianism, a kind of even more radical version of Protestantism, based on freedom of conscience, tolerance of other Christian communities (freedom of worship, we would say today) and the use of rationality in the interpretation of Scripture (thus, consequently, the rejection of dogma). Their word, from the territories of their preaching, crossed borders and spread throughout Europe. The street named after their family is flanked by the two others that complete the fabric on which the village’s network of alleys and chiassi is grafted, called, with shrewd popular icasticity, “via del Sole” and “via Oscura”, inside and outside the walls, respectively. The main vestiges of Buonconvento’s past unfold along them.

At the center is the Palazzo Podestarile, beside which stands the Clock Tower: on the façade, the twenty-five coats of arms of the podestas who ruled the village in ancient times tell us vast passages of its history. Not far away, on the same Via Soccini, is the Church of Saints Peter and Paul, the main one in the village: the façade, in late Baroque Sienese compound, yields to the charm of red brick and respects the chromatic unity of the village. It is the church where Emperor Arrigo VII died in 1313: inside, only a few works, such as the Madonna and Child with Angels by Matteo di Giovanni and a fresco depicting the ’Coronation of the Virgin, by an anonymous 15th-century artist, evoke the sumptuous furnishings the church once displayed to the faithful. The others require a visit to the Museum of Sacred Art of the Val d’Arbia, founded in 1926 by the village’s parish priest, Don Crescenzio Massari, and housed in the Palazzo Ricci Soccini: its collection includes works ranging from the 13th to the 20th century. Among these is one of the masterpieces of thirteenth-century Italian art, the splendid Madonna di Buonconvento, an extraordinary panel painting by Duccio di Buoninsegna, which was originally located in the church of Saints Peter and Paul. But there are other great Sienese painters of the 14th and 15th centuries to be found along the museum itinerary: Pietro Lorenzetti and Sano di Pietro above all, but also Luca di Tommè and Andrea di Bartolo, to arrive at the 17th century, where there is a conspicuous collection of canvases by the artists who, in those years, gave life in Siena to one of the most interesting (and also most underestimated) schools of painting of the period. Here, then, are works by Francesco Vanni, Rutilio Manetti, Ventura Salimbeni, and Bernardino Mei: this is the seventeenth-century Sienese school practically in its entirety. We walk along the medieval cobblestones of the alleys that connect Via Soccini to the others, observe the characteristic buildings of Via del Sole, once artisans’ workshops, come across surprising Art Nouveau episodes (so much so that in 1985 an exhibition was set up on the theme), stroll outside the walls in Via Oscura, and then resume our journey through the landscape, toward the Crete Senesi: ancient castles occasionally dot the hills. Apparently a great 18th-century English poet, Thomas Gray, passing through the Sienese countryside on his Grand Tour, had to write to his mother in a 1740 letter that from these lands “you will have the most beautiful view in this world.”

|

| Via Soccini. Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| The church of Saints Peter and Paul. Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| The Madonna by Matteo di Giovanni in the church of Saints Peter and Paul. Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| The Museum of Sacred Art of the Val d’Arbia. Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Duccio di Buoninsegna, Madonna of Buonconvento (late 13th century; tempera on panel, 68 x 49 cm; Buonconvento, Museo d’Arte Sacra della Val d’Arbia) |

|

| Buonconvento, the "happy place" in the center of the Arbia valley, in the Crete Senesi |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.