Between study and reflection: the Malatesta Library, the Renaissance dream of Malatesta Novello

In 2003, a conference celebrating anniversary number 550 since the opening of one of Italy’s most illustrious cultural jewels, the Biblioteca Malatestiana, opened in Cesena, and for such a gathering of scholars rooting in the Romagna city a particularly apt title was chosen: The Gift of Malatesta Novello. The Library would perhaps never have come into being without the figure of this enlightened patron, Domenico Malatesta (1418 - 1465), who in 1433, when he became knight palatine as well as lord of Cesena, decided to take on the nickname"Novello." The young lord had a dream: to spread humanistic culture in his city, as well as to bring luster and glory to his family through the arts. This was, in essence, what his brother Sigismondo (1417 - 1468) was about to do at exactly the same time with the Malatesta Temple in Rimini.

And it was precisely in 1450, the year in which the Rimini temple was consecrated, that in Cesena Malatesta Novello began to take an interest in the plans of the friars of the convent of San Francesco, who about three years earlier had finally been able to begin work on a building that could preserve the volumes collected over more than two hundred years of presence in Cesena. In 1445, in fact, Pope Eugene IV had granted the friars that a bequest they had obtained, and which was supposed to be used to build a chapel inside the friary, should instead be earmarked for the construction of a library. In 1448 the presence in the city of the architect Matteo Nuti was recorded, and a few years later he would place his name on the inscription recalling the date of the end of the work: we can therefore assume, though without certainty, that the construction of the building had begun precisely around 1448. But without having objective evidence, there are instead those who think that work began in 1450, when Malatesta Novello’s interest became tangible: that year, the lord donated to the friars codices worth a total of five hundred florins, a considerable sum for a donation that, in fact, sanctioned Malatesta Novello’s entry into the enterprise.

The design of the building was entrusted, as anticipated, to Matteo Nuti, and the work was supervised by both the friars and the lord of Cesena: still today, wandering around the Library, we can detect the two souls, that of the conventual tradition and that of Malatesta humanistic culture. These are two souls that we particularly recognize in the stylistic choices. It took just two years to finish the great hall of the Library, the work on which was completed in 1452, and another two years were needed to arrange the volumes: on August 15, 1454, as the date engraved on the wooden door made by the artist Cristoforo da San Giovanni in Persiceto also reminds us, the Malatesta Library was solemnly inaugurated and opened to the public. Yes, because studies conducted in the mid-twentieth century found that the Biblioteca Malatestiana is one of the oldest civic libraries in the world (there are even those who consider it the first civic library ever): scholars of the time could therefore go to the institution to borrow its volumes. There are also documents that testify to the fact that the Municipality of Cesena, especially when Malatesta Novello was alive, exercised tight control over everything that went on inside the library: the book collections were taken care of, interest was taken in their expansion, loans were checked, periodic checks were made that no books were missing, and a custodian was chosen, whose appointment was the responsibility of the municipal council. Malatesta Novello had in fact arranged, in an incredibly modern way, for the city council to take care of the library together with the monks. The lord, after all, cared a great deal about the institution, so much so that soon the library was joined, at his behest, by a copying workshop: the amanuenses active in Cesena, in about twenty years of activity ( printed books would later become widespread) produced one hundred and twenty codices.

|

| The remodeled entrance to the ancient convent that houses the Biblioteca Malatestiana |

|

| The wonderful (and perfectly preserved) hall of the Malatesta Library |

|

| The plutei |

|

| Ancient codices secured to the pluteus with iron chains |

Malatesta Novello’s great humanistic culture can even be perceived from the way the spaces inside thehall, now known as the Nuti hall, named after the architect who designed it, were organized. The latter studied, probably drawing on the work of Leon Battista Alberti (particularly De re aedificatoria), an environment divided into three naves, as if it were a church, covering them with cross vaults (the side naves) and a barrel vault (the central one). The environment was inspired by the first Renaissance library, the one designed by Michelozzo in 1444 for the monastery of San Marco in Florence, and was meant to suggest, according to Alberti’s principles, harmony and balance: with the spaces scanned, in always constant geometric relationships, by the elegant fluted stone columns, Matteo Nuti succeeded in creating arefined hall that responded well to the needs of readers. Lighting, for the side aisles, is provided by a dense series of small windows with pointed arches, two for each bay, which let sunlight penetrate and illuminate the reading shelf of the plutei, the wooden benches (pine, in our case) on which readers took their seats and to which the volumes were secured by means of chains whose function was to prevent the books from being removed from the Library, or from simply being swapped places, forcing the monks to have to relocate them. Even today it is still possible to see the ancient volumes of the Malatesta Library where they were originally kept: the Libraria Domini, as the Malatesta Library was known in ancient times (meaning “Library of the Lord”: and the Dominus in question is not the “Lord” understood as God, but is Malatesta Novello) is in fact theonly monastic-humanist library in the world to have been preserved intact both in the building, the furnishings, and the book collection. An oculus, in the Gothic style, opens on the back wall, illuminating instead the nave, which is devoid of plutei as it was meant to allow access to the pews of the side aisles.

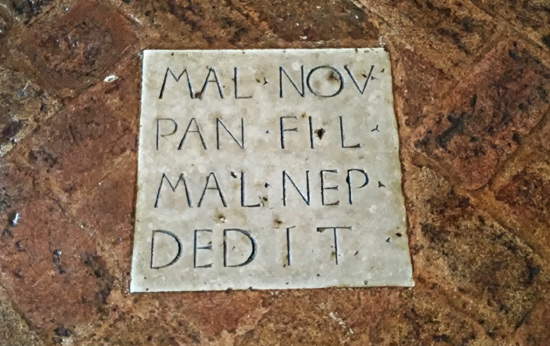

Abundant, as one might expect, are the symbols of the Malatesta dynasty. The entrance portal, made of local stone, greets us with theelephant, one of the Malatesta symbols par excellence, accompanied by the cartouche that reads the motto Elephas indicus culices non timet, “the Indian elephant does not fear mosquitoes,” signifying that magnanimous people do not care about the annoyances brought by small people. Next to the portal, a plaque immortalizes the name of the architect, who perhaps a little immodestly compared himself to the mythical Daedalus, builder of the Labyrinth of Crete: “MCCCCLII Matheus Nutius Fanensi ex urbe creatus Dedalus alter opus tantum deduxit ad unguem,” or “In the year 1452 Matteo Nuti, born in the city of Fano, as a new Daedalus brought to completion so great a work.” On the floor and lintel of the portal, an additional plaque commemorates the name of the person who donated the Library to the community: “Mal. Nov. Pan. Phil. Mal. Nep. Dedit,” meaning “Malatesta Novello, son of Pandolfo and grandson of Malatesta, donated.” Everywhere we see the symbols of the family, which we had already mentioned in the article dedicated to the Malatesta Temple, such as the three-headed enterprise, or the dog rose (several four-petaled roses, also in the Gothic style, decorate the wooden door), and the enterprise of the fence, which was proper to the Malatesta of Cesena, recurs frequently: since it resembles a suit of armor, the fence was a symbol of strength, but it is also common in the Library in that its original colors (white, red, and green, i.e., the colors of the theological virtues) are the same as those of the Library, namely, the white of the columns, the red of the terracotta used for the flooring, and the green of the walls and ceiling.

Even the ancient library endowment that Malatesta Novello wanted to assign to his Libraria reflects his humanistic culture: alongside the books of the Church Fathers (we are, after all, in a monastic library), we find books on history, a subject of which the lord was a great enthusiast, classical Greek and Latin authors (Pliny, Plutarch, Livy, Cicero), Hebrew codices, and works by contemporary humanists. Thanks to the efforts of Malatesta Novello, the far-sighted dual municipal and conventual control, and the great care taken by the people of Cesena in maintaining the Library, we can say that the Renaissance and humanistic dream of the lord and his city was not only fully realized, but continues to this day to be preserved intact to communicate, to the whole world, how important culture is and how important it is to keep it alive. The Library today is part of the UNESCO Memory of the World Registry, the program that protects historical archives, and can be visited (although one cannot linger among the plutei): as soon as we step through the still original door of the Nuti Hall, a true wonder opens up before us and we are surprised by an unusual emotion not only because we find ourselves in a historical environment perfectly preserved in its smallest details, enveloped in the same light that anciently illuminated the hall, but we can also taste the love of the people of Cesena for their city, becoming aware that culture also means the memory of our past from which it is possible to draw examples to guide our future.

|

| The entrance portal to the Library with the Malatestian elephants |

|

| Inscription attesting to the name of architect Matteo Nuti |

|

| Inscription commemorating the gift of Malatesta Novello |

|

| Coats of arms on the plutei |

|

| Column with the enterprise of the three heads |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.