Because innovation is written in Pisa's DNA

There is a thread that runs through the centuries and binds Pisa and its entire territory to a key concept of modernity:innovation. This is no accident or recent phenomenon: Pisa has always been, since ancient times, a laboratory of ideas, experiments and discoveries, capable of anticipating the times and leaving an indelible mark on the history of science, technology and culture. From the days when Leonardo Fibonacci introduced the positional numbering system of Indian origin to Europe to the modern startups of the Navacchio Technology Pole, Pisa has always been able to cultivate change. In between, we find the genius of Galileo Galilei who pointed his telescope to the heavens, revolutionizing forever the way we conceive of the universe, and then the avant-garde shipbuilding of the Republican Arsenals, the centuries-old excellence of theUniversity of Pisa, the birth ofItalian information technology, and even the energy transition with wind farms scattered throughout the territory.

If one thinks about the relationship between Pisa and innovation, the story goes back a long way. One could even go back to shortly after the year 1000: it was 1064 when the construction of the Pisa Cathedral began, the first building since antiquity to make use of Carrara marble by starting mining again on the Apuan quarries (and two centuries later, Nicola Pisano will be the first known great artist to move to Carrara for some time in order to choose the marbles and arrange their transportation, at the time when the artist was working on the pulpit of Siena Cathedral, although his workshop was based in Pisa and it was to Pisa that he had the blocks sent). But there is more to this story than just art.

The first name that could be made, risen almost to the ranks of legend, is that of Leonardo Fibonacci. Born around 1170, Fibonacci was the first great mathematician of medieval Europe. It was he who, in his Liber abbaci of 1202, first spoke of what is now known as the "Fibonacci sequence“ (or ”Fibonacci succession"), a succession of integers in which each number is the sum of the previous two (0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377, 610, 987, 1597, 2584, 4181, 6765, 10946 and so on). Various, even today, are the practical applications of this succession: in computer science (for some sorting algorithms), in botany (some flowers, it has been observed, have petals arranged according to the Fibonacci succession), in geometry and art (it is used to calculate the golden section), in economics (to predict the performance of stock market securities). However, the Liber abbaci has another revolutionary insight: the introduction of the positional numbering system of Indian origin to our continent. Growing up between Pisa and North Africa, Fibonacci realized the superiority of this system over Roman numerals, a system that would seal the fate of Western mathematics. The very concept of innovation is inscribed in Fibonacci’s biography: he was a pioneer of cross-cultural contamination, capable of seizing the Arab scientific vanguard and transforming it into a foundational element of modern calculus.

If we talk about innovation and Pisa, it is impossible not to mention then Galileo Galilei. Born right here in 1564, Galileo was the man who redefined the scientific method, laying the foundations of modern science. Observation, experiment and mathematics became, with him, instruments of knowledge in an age still dominated by Aristotelian speculations. It was in Pisa that Galileo began to question physics, studying the motion of bodies and debunking the dogma that objects of different weights would fall at different speeds. According to tradition, his challenge to Aristotelian theories culminated in the experiment from the Leaning Tower, although there is no documentary evidence of this event: it was primarily a thought experiment, although today it is almost considered one of the founding “myths” of Pisan pride (it is also found depicted in some works of art). What is certain is that Galileo Galilei’s Pisan research laid the foundation for a revolution that would change the world.

Thinking instead of innovation as the ability to look forward, the Pisan shipbuilding industry of the medieval centuries is a prime example. The Republican Arsenals, built beginning in the 13th century, were the beating heart of the Pisan navy, a cutting-edge shipbuilding industry that guaranteed the Republic of Pisa a central role in the Mediterranean and enabled it to be one of the greatest naval powers of its time. These shipyards were designed to quickly build and repair galleys, allowing the city to maintain an efficient and competitive fleet. Their role was not diminished when Pisa came under Florence: in fact, the Florentines built a new complex designed by Bernardo Buontalenti, the Arsenali Medicei, which would continue the traditional Pisan shipbuilding industry with new vigor. The Arsenals have been restored: the Medici ones now house the Museo delle Navi Antiche di Pisa, where wrecks from Roman and medieval times can be admired, witnesses to a time when Pisa dictated the rules of navigation, while the Republican Arsenals are home to temporary exhibitions.

Much of the innovation in Pisa’s history comes, as one might expect, from its university. Founded in 1343, theUniversity of Pisa, attended by Galileo Galilei, is one of the oldest academic institutions in Italy and Europe. For centuries it has been a center of excellence for research and innovation, with discoveries ranging from physics to medicine, biology to engineering. Today, the University of Pisa is at the center of cutting-edge projects in areas such as artificial intelligence, robotics and life sciences. The “Enrico Piaggio” Research Center has developed advanced technologies such as bio-inspired robots (i.e., robotic systems that mimic the behavior of living beings), bionic prosthetics, robots with soft materials for medical and industrial applications, underwater robotics, and more. Many archaeological missions led by the University of Pisa outside national borders, not to mention discoveries in the fields of medicine, biotechnology, and innovative therapies. The link between knowledge and territory also manifests itself with the Scuola Normale Superiore and the Scuola Sant’Anna, elite institutions that attract talent from around the world and help make Pisa a city of knowledge.

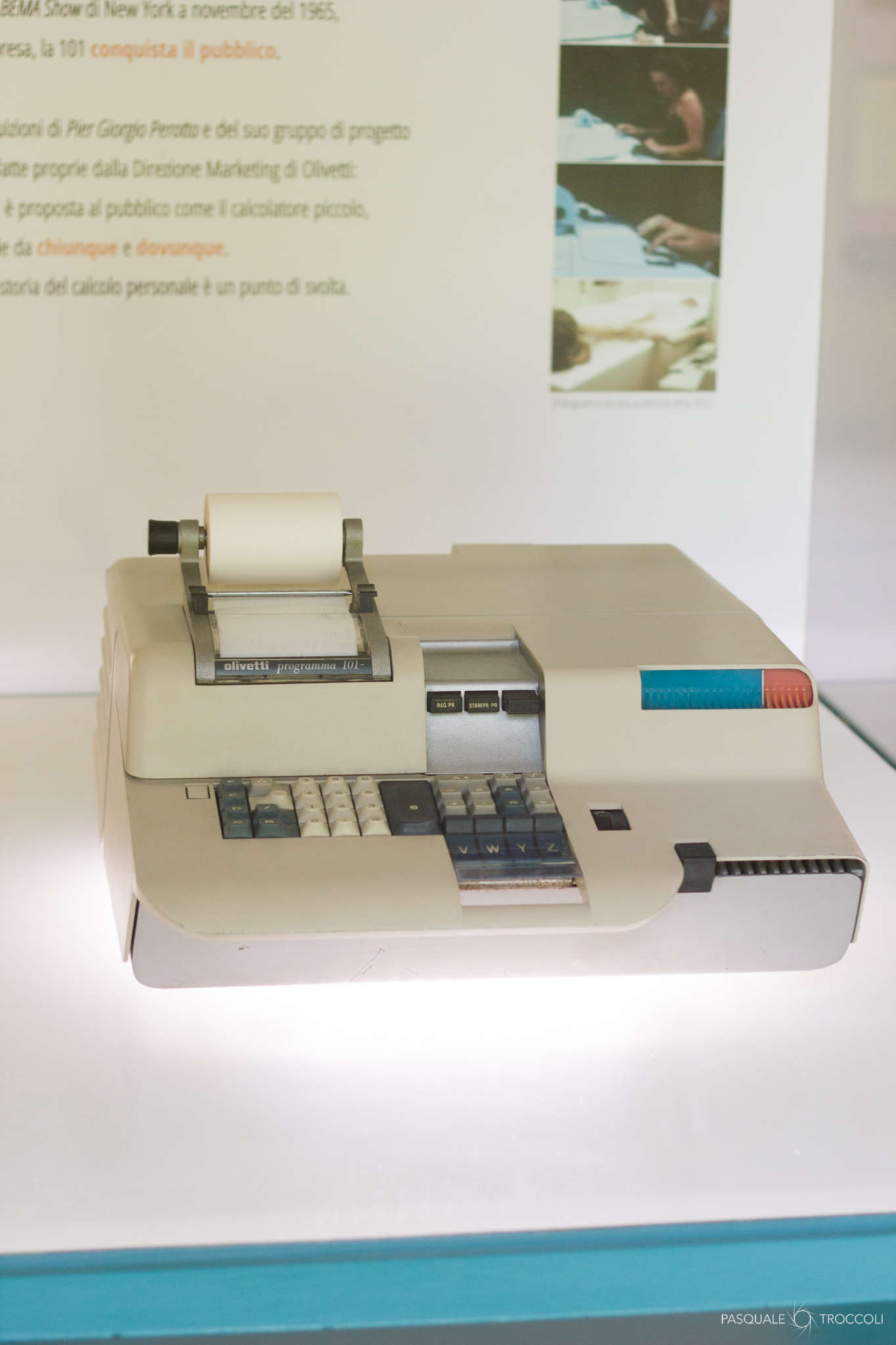

However, having to choose one area in which Pisa has historically been a beacon of innovation, one could mentioninformation technology: in fact, not everyone knows that Pisa was the cradle of Italian information technology. In 1961, within the University of Pisa, the first Italian electronic calculator was developed and turned on: the CEP (Calcolatrice Elettronica Pisana), which took seven years to develop (it was such an important project that the then President of the Republic Giovanni Gronchi was present at the machine’s inauguration). The result of collaboration between the university and Olivetti, the CEP represented a decisive step toward the modernization of the country, paving the way for computer research in Italy. And again, in Pisa, in the very Olivetti laboratories that were based in the city, the first PC in history was born, the Olivetti Programma 101, designed between 1962 and 1964 by a team led by visionary engineer Pier Giorgio Perotto, and with a cutting-edge design created by Mario Bellini. Even today, Pisa is still a landmark in the field, with advanced research centers and an ecosystem ranging from tech startups to artificial intelligence applications.

Innovation in Pisa also manifests itself in the challenges of the present and the future. The area was among the first in Italy to invest in renewable energy, with wind farms dotting the hills of Pisa and contributing to the ecological transition. The province of Pisa has invested significantly in wind energy, contributing to the production of renewable energy in Tuscany: the Pontedera Wind Farm is probably the best known and most visible of the Pisan wind farms, with its four wind turbines producing about 10 Gwh of electricity annually, covering the energy needs of more than 3,000 households and reducing CO₂ emissions by about 3,000 tons per year. However, the province is dotted with wind power plants, and it is the one in Tuscany that produces the most energy from this source: next to the Pontedera park, which opened in 2008, there is the Monte Vitalba park in Chianni, the first one, opened in 2006, joined by those in Montecatini Val di Cecina, Riparbella and Santa Luce. These installations demonstrate how the province of Pisa continues to be at the forefront of adapting to global changes, exploiting natural resources with a view to sustainability.

However, the entire territory of the province of Pisa is dotted with state-of-the-art facilities, research centers and more. A fewscattered examples: a few kilometers from the center of Pisa stands the Navacchio Technology Pole, an innovation hub that hosts startups, companies and research centers. Founded in the late 1990s, this hub has become a reference point for technology transfer and digital innovation, with projects ranging from robotics to artificial intelligence, from cybersecurity to biotechnology. Cascina , on the other hand, is home to Virgo, one of only three observatories in the world capable of detecting gravitational waves, a fundamental tool for studying phenomena occurring in the universe. It is basically a large interferometer with arms of 3 kilometers each, designed to measure tiny variations in distances caused by the passage of gravitational waves. It is operated by the European Gravitational Observatory (EGO), an international consortium founded in 2000 by the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) and the Italian National Institute of Nuclear Physics (INFN). It was later joined by Nikhef of the Netherlands. The Virgo collaboration includes more than 280 scientists and engineers from institutions in France, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Hungary and Spain. Still, in Pontedera, Piaggio is an emblematic example of how innovation can arise from the meeting of industrial tradition and advanced research. Since its founding, this historic company has never limited itself to producing simple means of transportation, but has constantly reinvented the very concept of mobility. The Vespa, a true icon of style and functionality, is the first great example: born in the postwar period as an affordable solution for travel, it has become an international symbol of efficiency and design, unfailingly associated with Italy in the collective imagination.

Today, Piaggio’s innovation manifests itself in multiple directions. On the one hand, the company has embraced the sustainable mobility revolution, with the development of the Vespa Elettrica and the study of new models with low environmental impact. On the other, it has been able to look beyond the traditional two-wheeler sector, investing in robotics and artificial intelligence projects. A concrete example of this evolution is Piaggio Fast Forward, the division set up to explore the frontiers of intelligent mobility, which has given rise to innovative devices such as Gita, an autonomous robot designed to make it easier for people to move around cities. But innovation is not just about products: it is an ecosystem, and this is where the link between Piaggio and the Pisa area becomes even more evident. The company has fostered the growth of an advanced technological district, collaborating with academic realities of excellence such as theUniversity of Pisa and the Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna. Thanks to these synergies, Pontedera has become a research hub in the fields of mechatronics, robotics andartificial intelligence applied to transportation. The Sant’Anna Valdera Pole, a detached section of the Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna of Pisa established in 2002, for example, has arisen precisely with this in mind (based, moreover, in Piaggio warehouses), developing cutting-edge projects in the fields of robotics, bioengineering, biotechnology and information technology: bionic prosthetics and robots of various kinds are among the most prized fruits of this pole of excellence.

Pisa, in short, is not only history, but also the future. An area that has always been able to reinvent itself, transforming knowledge and intuition into concrete progress. From Galileo’s science to Fibonacci’s mathematics, from information technology to wind farms, Pisa is a crossroads of innovation that has spanned the centuries. Today, this vocation has not faded: between academic research, startups, information technology, robotics and sustainability, the province of Pisa continues to be a fervent laboratory of ideas, where the past and the future intertwine in a constant dialogue. Innovation here is not just an abstract concept. It is a hallmark, a legacy that is renewed every day.

|

| Because innovation is written in Pisa's DNA |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.