by Redazione , published on 05/11/2020

Categories: Travel

/ Disclaimer

Barga is a richly evocative place: medieval art, elegant Renaissance palaces, the village dear to Giovanni Pascoli. A tour of the town in the Middle Serchio Valley.

Barga is said to be the only town in the world where it is possible to see two sunsets. It happens only twice a year: between January 29 and 31 and between November 10 and 12. It is on these dates that the right conditions occur: the sun first disappears behind the outline of the Apuan Alps, only to reappear, after a few minutes, through the arch of Mount Forato, which is lower than the line of the mountains and owes its name to its very special peak, which appears as if pierced, forming a large eye, where the sun passes after disappearing from the view of those who stop for a few moments on the belvedere of the Duomo, in the highest part of the historic center.

Giovanni Pascoli, who in a hamlet of Barga, Castelvecchio (later, in his honor, Castelvecchio Pascoli), had bought a house, knew this well: “I often spend the evenings on this terrace,” he had said in an interview with the Secolo XIX in May 1903, “I look at Barga going to bed and I see it up there, on the hill, shining like an altar.” From here, in fact, one not only admires the spectacle of the sun, but also enjoys a magnificent view of the whole town. The imposing square bell tower of the Cathedral of San Cristoforo is the one that inspired the poet L’ora di Barga: “To my little corner, whence I hear / but the rests brusir of grain, / the sound of the hours comes with the wind / from the unseen mountain village: / sound that equal, that bland falls, / like a voice that persuades.” The Romanesque-era cathedral, on the other hand, is one of the most imposing and remarkable in all of Tuscany. Its appearance has remained virtually unchanged for centuries: only the ruinous earthquake of 1920 caused serious damage to the structure, but the restorations that followed attempted to restore the collegiate church to its original appearance. The church is a precious treasure trove of medieval art: outside stands a 12th-century relief attributed to Biduino, depicting a miracle of St. Nicholas. Inside, the very fine early 13th-century pulpit, one of the most magnificent and best-preserved before Nicola and Giovanni Pisano, attributed to a pupil of Guido Bigarelli da Como, is surprising: its case is decorated with reliefs depicting theAdoration of the Magi, the Nativity, theAnnunciation, and on the fourth side the prophet Isaiah remains solitary. In the side chapels, 17th-century canvases, a sumptuous 14th-century painted cross that is striking for its exceptional state of preservation, Della Robbia terracottas. And finally, in the largest niche in the apse, with its stained-glass window designed by Lorenzo di Credi, the faithful are greeted by the colossal wooden statue of St. Christopher, the town’s patron saint, dating from the late 12th century, which has become almost a symbol of Barga.

|

| View of Barga, dominated by the cathedral |

|

| View of Barga from the belvedere of the Duomo. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The Duomo of Barga. Ph. Credit Davide Papalini |

|

| Interior of the Cathedral of Barga. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| The pulpit of the cathedral. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The colossal statue of St. Christopher. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

And in front of this huge statue one can imagine, at the beginning of the twentieth century, the painter Alberto Magri coming here and staring at it in his notebooks and then on his canvases, attracted as he was by the art of the primitives, he who, before arriving in Barga, the village oforigin of his parents, had studied at the Normale in Pisa, had been in Paris in the very years when the French city was the world capital of art, but then decided to return here, to the place of his childhood (perhaps because he was attracted by the poetics of Giovanni Pascoli’s Fanciullino: “you are the eternal child, who sees everything with wonder, everything as if for the first time”), to give birth, along with other Tuscans such as Lorenzo Viani, Adolfo Balduini and Spartaco Carlini, to one of the most interesting experiences of Italian primitivism, although still little known today. Here, in Barga, Alberto Magri had found his Arcadia, to use the words of historian Umberto Sereni, and those works of his that were so genuine, characterized by their almost childlike forms, though traced with the awareness of an artist who had studied a great deal (especially Italian art before the fifteenth century) and was in contact with many of the greats of his time, had fascinated Umberto Boccioni and Leonardo Bistolfi, to name a couple of names.

Alberto Magri’s house is still there, it’s at the foot of the cathedral: just walk up a ramp to be on the terrace from where Pascoli watched the sunsets, or walk through the meadow that was once thearringo, the square where the gatherings of the people were held, just opposite the 14th-century Palazzo Pretorio, which is now home to the Civic Museum. Beneath the terrace, there is an intricate network of alleys that at the steepest points become stairways, get lost among the tall buildings, become almost hidden tunnels, to be explored with the favor of darkness. And then, whichever alley one takes, one will invariably find oneself in the Via di Mezzo, the elegant central street overlooked by the city’s most beautiful palaces, which, despite its proximity to Lucca, since 1341, was subject to the authority of Florence, which exercised it first together with the Lucchese, and then, from 1347, alone: this is therefore why, strolling through the streets of Barga, it almost seems as if one were in a small mountain Florence, given the abundance of elegant Renaissance buildings (such as Palazzo Pancrazi, the seat of the town hall, or Palazzo Balduini, or even Palazzo Angeli), with their sober and orderly facades, their portals and their large windows framed by stone arches, the Medici coats of arms that one occasionally encounters on some wall.

In the heart of the village are two other Pascolian testimonies. The first is the Loggia del Mercato: it was built by Cosimo I de’ Medici, to replace the older loggia (which hindered the project of the nobleman Martino Pancrazi, who wanted to build his palace on this land: Palazzo Pancrazi, precisely), and then at the end of the 19th century it was transformed into a café, which still exists, by the Swiss Capretz family, who settled in Barga in those years. Apparently Pascoli often happened to have coffee under the Loggia. The second is the 18th-century Teatro dei Differenti: it was here that the poet delivered the oration La grande proletaria s’è mossa in 1911.

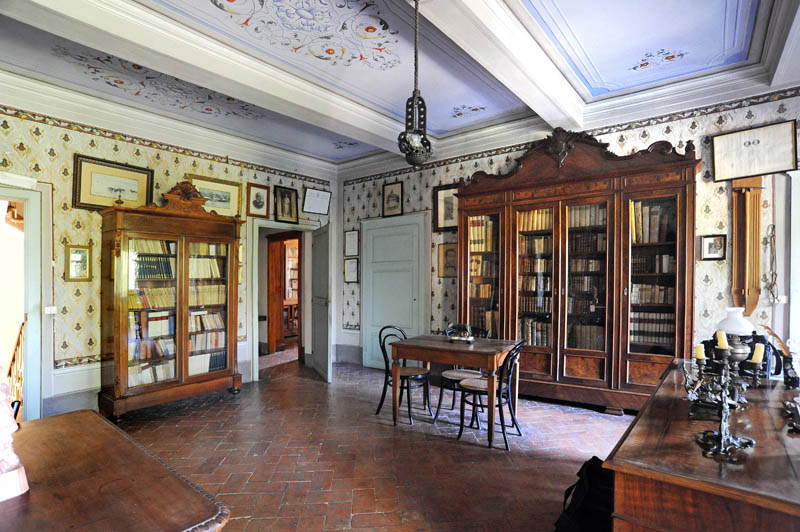

Pascoli today rests inside Bistolfi’s sarcophagus preserved in the chapel of his house in Castelvecchio: the dwelling that the poet bought in 1895, perfectly preserved thanks to the passionate work of his sister Maria who until 1953, the year of his death, kept it in excellent condition, can be visited today. Everything is practically as it was then. The artwork on the walls, by artists such as Plinio Nomellini, Adolfo Tommasi and others (and there is also a small painting by Alberto Magri). The three desks where Pascoli worked, each dedicated to a different activity. The two rooms, his and his sister’s, the kitchen with still its dishes, the dining room, the rich library. And then the altana from which the poet and Mariù enjoyed, on summer evenings, the view of the Media Valle del Serchio. A few steps away is the small church of San Niccolò, in front of which stands the altar that Plinio Nomellini dedicated to the poet and which was later turned into a monument to the fallen soldiers of World War I. Behind the house is the small village of Castelvecchio, a few souls inhabiting its small stone houses gathered around the small square, named after another poet, Giorgio Caproni. Little has changed since these cobblestones under the ridge of the Ciocco hill walked the “maidens of Castelvecchio” who fetched water to take to the houses, “on their heads the pitcher, sharp as a mirror, balancing trembling.”

|

| Alley in the historic center of Barga. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Palazzo Pancrazi and Loggia del Mercato. Ph. Credit H.P. Schaefer |

|

| The Market Loggia, now home to the Capretz Café. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Giovanni Pascoli’s house in Castelvecchio. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Giovanni Pascoli’s house in Castelvecchio. Ph. Credit Soprintendenza Archivistica e Bibliografica della Toscana. |

|

| Plinio Nomellini’s altar. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Meadows in Castelvecchio. Ph. Credit Finestre sull’Arte |

Article written by the editorial staff of Finestre sull’Arte for UnicoopFirenze’s “Toscana da scoprire” campaign.

|

| Barga, the town of two sunsets: a little mountain Florence |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.