Animals and fantastic places in the museums of Italy: Trentino-South Tyrol

Nineteenth and penultimate leg of our journey to discover animals and fantastic places in Italian museums. Today we travel to Trentino-Alto Adige to find out what creatures lurk in the institutions of Italy’s northernmost region. The project is carried out by Finestre Sull’Arte in collaboration with the Ministry of Culture to bring the public to discover Italian museums, safe places suitable for everyone, from a different point of view than usual. Let’s start our journey through the mountains!

1. Leonardo Bistolfi’s Sphinx at the Mart in Rovereto.

A fascinating work executed in Carrara marble, the Sphinx by Piedmontese sculptor Leonardo Bistolfi (Casale Monferrato, 1859 - La Loggia, 1933) is the model for the funerary monument that the artist made for the Pansa family in the Cuneo cemetery, where it can be seen, and is preserved at the Mart in Rovereto where it is on deposit from a private collection. Conceived in 1889, the monument was installed in Cuneo’s cemetery in 1892. Bistolfi had his own very particular idea of the sphinx, the mythological being with the body of a lion and a female face: in his work, in fact, the sphinx is nothing but a personification of death. “The original idea,” he explained in 1896 to British journalist Helen Zimmern, “was to represent with a symbolic figure Death, Death as we moderns see it; although we shed no tears for the cruel pains of the Eternal Father’s Hell-fire, we are always disturbed and disquieted by the elusive thought of the unknown infinite. In expressing this idea, almost unconsciously, and certainly without premeditation, the figure of Death took on the appearance of a sphinx.” The work was a great success: Bistolfi’s sphinx divides the work into two parts, the one on his right filled with flowers (poppies, chrysanthemums, lilies) and the one on his left completely empty, an allusion to life on one side and death on the other.

2. Alberto Savinio’s Polyphemus at the Mart in Rovereto.

It is not a traditional depiction that Alberto Savinio (Alberto de Chirico; Athens, 1891 - Rome, 1952) offers the observer of the story of Ulysses and Polyphemus, told by Homer in theOdyssey: having arrived at the cave of the Cyclops Polyphemus, the Greek hero was forced to blind the monstrous and violent being in order to escape him, having already lost some of his companions to him. In Savinio’s painting, the depiction takes on the contours of a dream: the moment is that of Odysseus’ escape, who is already on his ship setting sail. Polyphemus is depicted as an agglomeration of decorated objects of various shapes and colors, while Ulysses is represented only by his boat: this is the way Savinio uses to contrast Polyphemus’ disorder, chaos, and violence on the one hand and Ulysses’ reason, intelligence, and spirit of adventure on the other.

3. Romanino’s Unicorn at Buonconsiglio Castle.

Romanino (Girolamo Romani; Brescia, 1485 - 1566) decorated the Loggia Grande of the Buonconsiglio Castle (also known today as the “Loggia del Romanino” because it is totally related to his paintings) between 1531 and 1532, commissioned by Bishop Prince Bernardo Clesio. The powerful patron wanted a work done economically, which avoided unseemly subjects and, above all, was easy to read (so much so that he lacked the figure of an intellectual to elaborate the iconographic program). On the subject, therefore, Clesio granted wide freedom to Romanino, suggesting, however, the realization of “some fabula de Ovidio.” In short, there were no precise indications, and Romanino therefore ranged from biblical episodes to mythological subjects to allegories. The Brescian artist also frescoed the room adjoining the Loggia, the Corridor of the Kitchens, so called because it connected the Loggia with the kitchens. Among the frescoes is an unusual lady with a unicorn: similar depictions were not uncommon in 16th-century art (think of Raphael Sanzio ’s Lady with the Unicorn preserved in the Galleria Borghese), as the unicorn was considered a symbol of purity and chastity (in fact, in the Middle Ages it was believed that its horn had thaumaturgic power and acted as a universal antidote for all poisons), and according to the beliefs of the time it was believed that, once it met a virgin, it would run to her and after resting its snout on her lap it would fall asleep (hence the reason for the peculiar pose of Romanino’s unicorn). You can find an in-depth look at Romanino’s Loggia in our magazine.

Romanino

Romanino4. Friedrich Pacher’s unicorn hunt in the Dominican church in Bolzano.

Another unicorn can be seen in a fresco in the Dominican church (Dominikanerkirche) in Bolzano. It is the work of Austrian painter Friedrich Pacher (Novacella, c. 1440 - Bruneck, 1508) and is located in the lunette of the first arch of the church’s cloister. It dates from around 1496 and features a rather complex iconography of medieval origin: the depiction, which originated in the secular sphere in the Middle Ages, is here linked to the Gospel episode of the Annunciation. Indeed, we see the archangel Gabriel on the left greeting the Virgin Mary on the right: the archangel appears with four dogs on a leash (symbolizing Justice, Truth, Mercy and Peace), intending to chase away the unicorn. The mythological animal runs toward Our Lady and is about to be taken in by her: in fact, it was believed, as mentioned above, that only a Virgin was able to catch and tame it. The archangel therefore urges him toward her. It appears clear here, scholar Laura Dal Prà has written, “the desire to celebrate in the context of a growing devotion to the figure of Mary the mystery of her virginity declined with a review of typological elements arranged around the equally symbolic scene of the unicorn and the virgin.”

5. Paolo De Matteis’s Hydra at Thun Castle.

According to Greek mythology, the Hydra of Lerna was a monstrous animal, a great sea serpent with nine heads capable of killing only by breathing. An animal endowed with supreme intelligence, it also had another unpleasant characteristic for those who had to face it: its heads, if severed, grew back. The daughter of Typhon and Echidna, she terrorized the inhabitants of the city of Lerna in Argolis: she was killed by Hercules during the second effort, thanks to the help of Iolaus, who prevented the heads from growing back by cauterizing the wounds. It was thus easier for Hercules to use a boulder to crush her central head. In the painting by Paolo De Matteis (Piano Vetrale, 1662 - Naples, 1728), a Campanian painter and one of the leading exponents of the late Baroque period, the Hydra is now harmless, slumped to the ground, defeated, while Hercules, unperturbed, leaning on his club, contemplates the monster seriously and absorbed, while receiving from a cupid a crown, the symbol of victory.

6. The knight and the dragon at Avio Castle.

What better place than an ancient castle to host a fairy-tale depiction of a knight fighting a fierce dragon? The Castle of Avio, one of the most ancient in Trentino, in fact houses, in the House of the Guards (one of its component buildings), a series of 14th-century frescoes depicting duels and battles, which were meant to serve as a reminder of what elements were useful in the training of the knight, including also a scene depicting a fight between a knight and a dragon, which is unfortunately fragmentary (the horse’s front legs and practically the entire body of the monster are missing, of which only the neck, head, and an additional head that is threatening the equine’s hind legs remain). We do not know who the author of the frescoes was, probably a Trentino artist of the mid-14th century who trained in Verona but also looked to painting beyond the Alps. The knight with the dragon most likely recalls depictions of St. George, who in the Middle Ages was always represented in the act of saving the princess from a fearsome dragon, and expresses the courtly taste for fairy tales whose protagonists are heroes, like our knight, who express their courage and daring by trying their hand at feats on the edge of the impossible such as, precisely, defeating a monstrous creature.

7. The dragon of St. George in the church of San Martino in Campiglio

The church of San Martino in Campiglio, a town just outside Bolzano, preserves one of the most interesting and best-preserved 15th-century cycles in South Tyrol. However, we do not know who their author is. On the outer wall is an image, unfortunately much ruined because of its location, of St. George defeating the dragon, saving the princess. According to legend, in fact, St. George found himself passing through the city of Silena in Libya, whose inhabitants were terrorized by a terrible dragon that had to be appeased with two sheep a day, but when the sheep began to run out, the inhabitants decided to sacrifice a sheep and a young man from the city. One day it was the king’s daughter’s turn: despite the ruler’s attempts to save her life, her fate appeared sealed. The young knight George, knowing the fate the maiden was facing, helped her in the name of Christ and, with his horse, faced the dragon, defeating it with his lance. In Campiglio’s fresco we see St. George hurling himself at the being, already on the ground, while the princess assists in the background: although the state of preservation of the scene is not optimal, it is interesting to note how the dragon, rather than a snake as is most often the case, resembles here a monstrous bird.

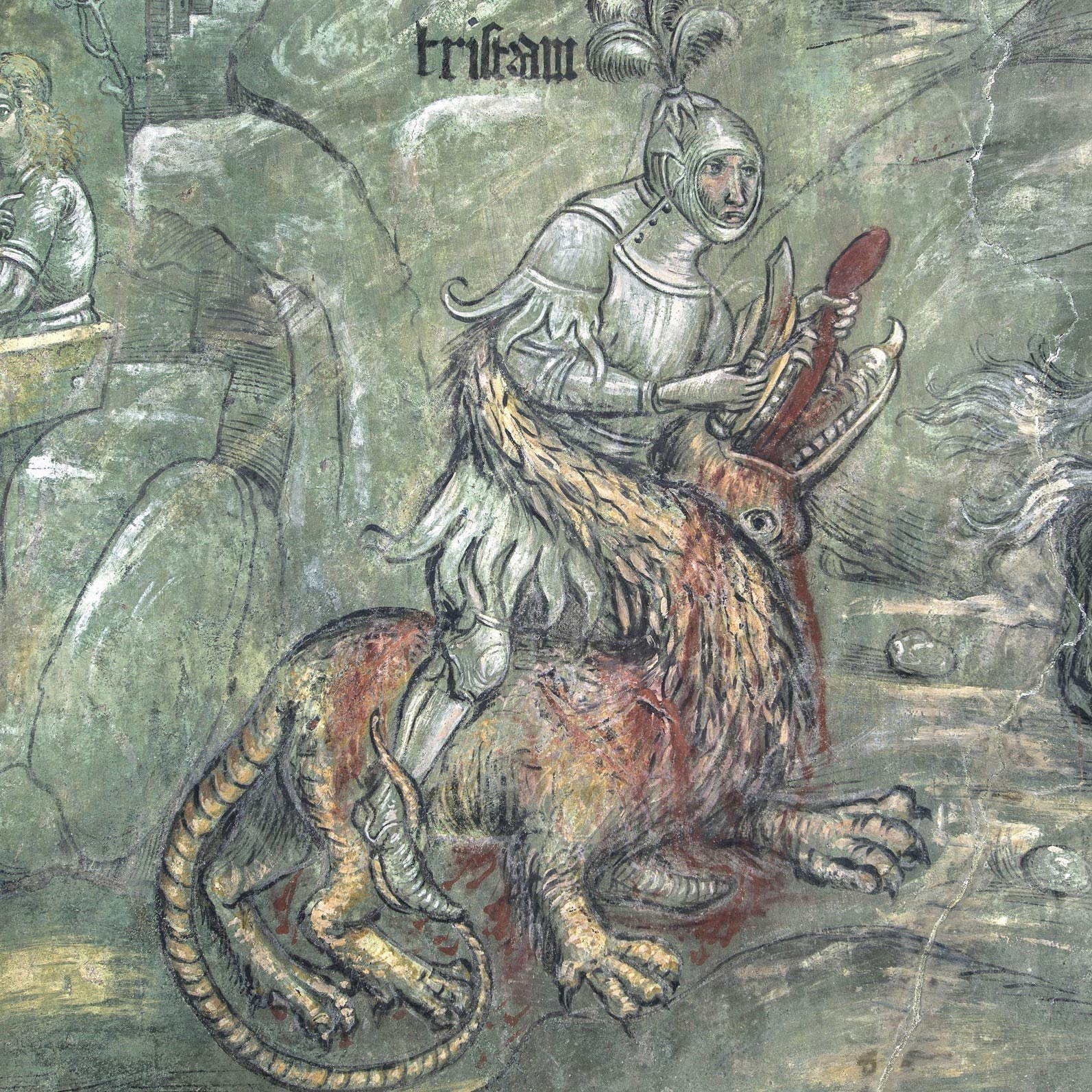

8. Tristan and the dragon at Roncolo Castle.

In the halls of Runkelstein Castle (Schloss Runkelstein), a medieval castle that sits atop a rocky outcrop near Renon, is an important 14th-century decorative cycle illustrating many aspects of court life in the Middle Ages, as well as various fables and legends. Among these is that of Tristan slaying the dragon: the Breton legend of Tristan and Isolde in fact told that a royal edict had been issued in Ireland that whoever managed to slay a menacing dragon could take Princess Isolde as his bride. Tristan confronted the monster, killed it by cutting out its tongue for proof of the feat. However, the dragon’s poison made him faint, and a rival of his, Agingherranus, brought the dragon’s head to the king’s palace to take credit for it. It would later be Isolde who discovered the truth. In the Roncolo Castle fresco, Tristan is depicted astride the dragon just as he is intent, with great concentration, on cutting out the dragon’s tongue, grasping it with one hand and holding a knife with the other. Note how Tristan is cataphracted in his heavy armor, typical of a medieval knight. The episode is part of a cycle depicting the stories of Tristan and Isolde: the author of the frescoes is unknown to us.

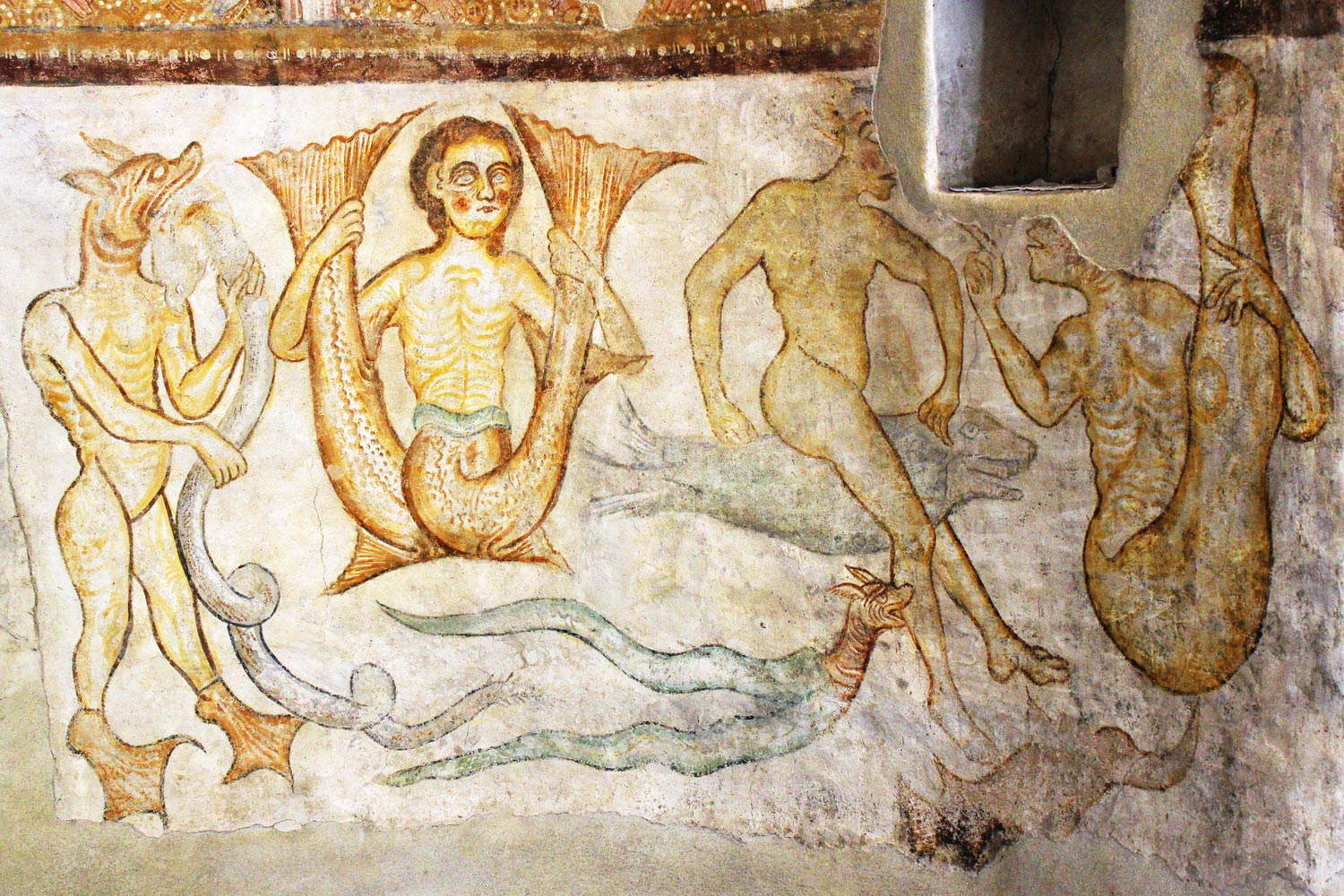

9. The mermaid of the church of San Giacomo in Termeno

In the church of St. James in Tramin, a placid village located on the Wine Road, there is a series of unusual depictions of fantastic animals: a centaur, a triton, strange sea monsters including one with the body of a man, the head of a dog and webbed feet, the rare depiction of a sciapode (a being believed to live in India and to have only one foot, with which it was thought to cast shade), and even a mermaid with a double fish tail, repeating an iconography that had spread since the 9th century (according to Greek mythology, the mermaid was instead half woman and half bird). The frescoes date from the 13th century and respond to the idea of arranging on the wall of the church a kind of bestiary, or collection of animals (in this case fantastic) that could be linked to certain symbolism. The bicaudate (i.e., double-tailed) mermaid was often depicted in medieval churches: we do not know well why the insistence on this mythological creature, but it is likely that it was associated with the sin of lust.

10. The karnyx from the Rhaetian Museum in Sanzeno.

The karnyx was a Celtic musical instrument (its use is attested between 300 B.C. and 200 A.D.), a kind of large trumpet ending in the head of an animal, real or fantastic. In the 1950s, in Sanzeno, in Val di Non, some fragments of the barrel of a karnyx were found by the archaeologist Giulia Fogolari: it was the first find of its kind in the region (moreover, for a long time it was not understood what those fragments were: it could only be discovered thanks to the comparison with some karnykes found in France), and in itself finds of karnyx remains are very rare. In Italy, the only other such find was in Castiglione delle Stiviere, in the province of Mantua. For this reason, the Superintendence of the Autonomous Province in 2008 initiated a research project on the karnyx found in Sanzeno, which then culminated in the accurate reconstruction of the musical instrument. It is believed, based on literary sources, that the karnyx was used primarily in battle, by virtue of its imposing appearance (it reached almost two meters in height, plus the animal-shaped protome was supposed to instill fear). It was played by holding it upright so that the snout of the beast could be seen clearly. The reconstruction now in the Rhaetian Museum in Sanzeno was made in bronze at the Ervas forge, and features a boar-headed protome: not a fantastic animal, all right, but one that in ancient times had an appearance that made it look unrealistic and similar to a legendary creature.

|

| Animals and fantastic places in the museums of Italy: Trentino-South Tyrol |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.