Calabria is the thirteenth stop on the journey among fantastic animals in Italian museums: from Reggio Calabria to Kaulon, from Vibo Valentia to Cosenza, mermaids, dragons, sphinxes, sea monsters and more arrive. The project is led by Finestre Sull’Arte in collaboration with the Ministry of Culture and aims to take the public to discover Italian museums, safe places suitable for everyone, from a different point of view and discovering unusual paths. Here are the fantastic creatures we found in Calabria!

According to Greek mythology, the sphinx was an animal with the head and breasts of a woman, the body of a dog, the wings of an eagle, the paws of a lion, and the tail of a snake: it stood on a cliff along the road to Thebes and submitted a riddle to travelers who happened to pass by, and if they were unable to give the correct answer they were devoured. It was the hero Oedipus who answered correctly, and the sphinx, defeated, threw himself off the cliff. At the Medma-Rosarno Archaeological Museum the sphinx is depicted on an “arula,” or small terracotta altar decorated in relief, which usually depicted mythological scenes. The arulae date from the late fifth to the first half of the fourth century BCE and were found in minor shrines, those where there were no monumental altars: these were, for example, shrines intended for small communities, or shrines that were located in necropolises. However, it is possible that arulae were also votive offerings that were offered to deities. In this case, the arula in the Medma-Rosarno Museum features a sphinx between two Ionic columns, and it comes from a necropolis itself. It arrived at the museum in 1986, donated by Professor Giovanni Gangemi, an elementary school teacher and a great lover of Medma’s archaeology, so much so that in 1991 he was appointed honorary inspector of the Superintendency of Calabria.

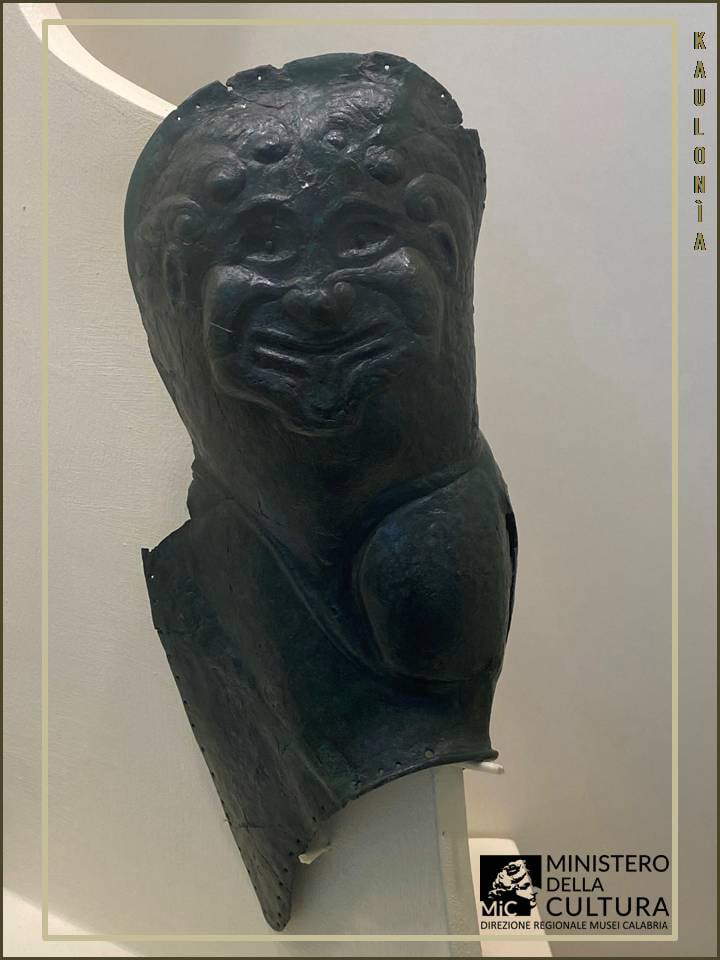

The gorgons, according to Greek mythology, were three sisters (Steno, Euryale and the more famous Medusa) who had snakes instead of hair and were able to petrify with their gaze anyone who looked at them. This object preserved at the Archaeological Museum of Ancient Kaulon is very special: it is one of the rare shoulder straps found in Magna Graecia, and it is decorated with the protome (a decorative element consisting of the head alone) of a gorgon, described with almond-shaped eyes, an open mouth, and hair in curly locks to evoke snakes. The shoulder strap was an element of a hoplite’s armor (hoplites were the heavy infantry soldiers of the armies of ancient Greece), and was placed between the deltoid and humerus to protect that delicate part of the body. The artifact was found as a votive offering near ancient Kaulon, dates to the last quarter of the 6th century B.C., and is an interesting testimony to the ancient toreutic art, or metalworking.

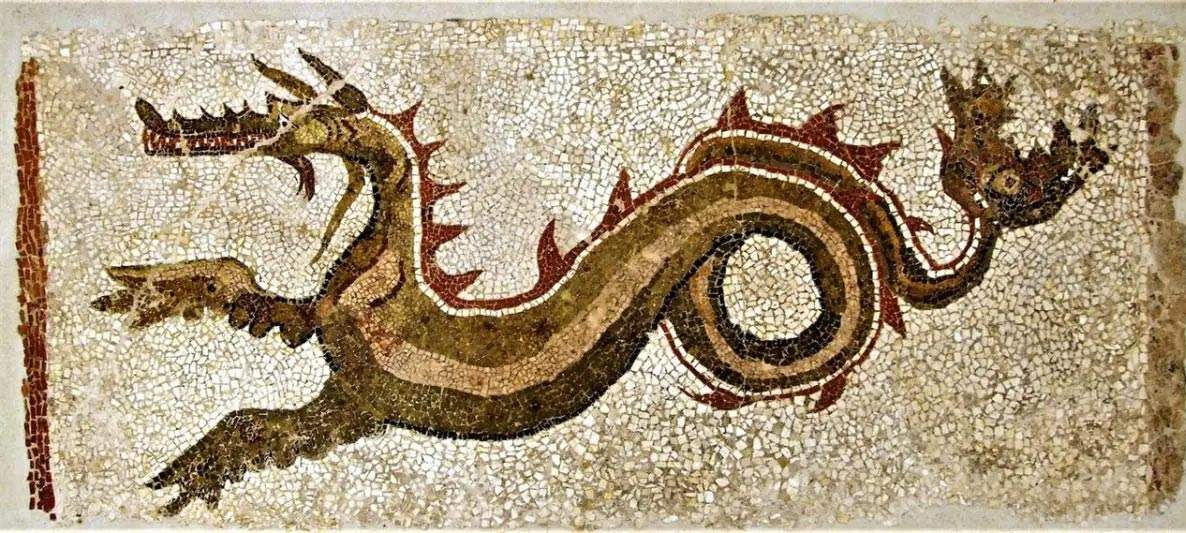

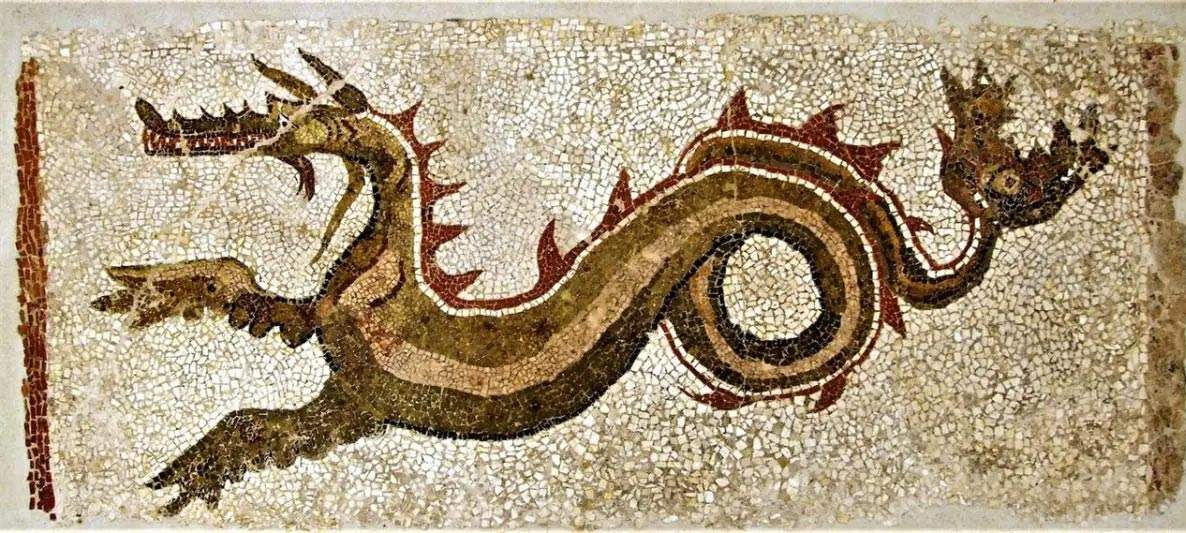

As many as two dragons can be found at the Museum and Archaeological Park of Ancient Kaulon, both made of mosaic. One of them was recently discovered in 2012 by the Archaeological Superintendence of Calabria as part of research activities at the site of Kaulon, a Magna Graecia colony founded near Punta Stilo, not far from present-day Monasterace. The mosaic, depicting a dragon and a dolphin, covers an area of about 30 square meters and is believed to be one of the most important and ancient (in fact, it dates back to the 4th-3rd centuries B.C.) found in the area of ancient Magna Graecia. It decorated the floor of a warm bathing pool in a spa area: usually, in fact, the floors of the baths were decorated with mosaics depicting sea creatures, including monsters such as the sea dragon in question, to evoke the element of water. The other mosaic, which depicts a sea dragon similar to the one in the bath building (thus with a long, sinuous body, suitable for swimming, with fins and a tail resembling that of a fish), decorated a room (the entrance to the dining room) of the “dragon house” (so named precisely by the mosaic), and dates from the second half of the 3rd century BCE.C.: long on display at the National Archaeological Museum in Reggio Calabria, it is now perhaps the best-known work in the Archaeological Museum of ancient Kaulon.

It is called a pinax (plural pinakes), literally “picture,” a votive tablet that could be made of painted wood, terracotta, marble or bronze, and that in ancient Greece hung on the walls of sanctuaries or on sacred trees. Not many pinakes are preserved in Italian museums, and most of them are found in museums in Magna Graecia, such as the National Archaeological Museum in Reggio Calabria: They usually depicted mythological scenes, and the Reggio institution preserves one with the abduction of Persephone, the daughter of Demeter, goddess of the harvest and crops, by Hades, the god of the underworld, who had fallen in love with her and took her with him to the underworld to make her his bride (according to the myth, Persephone spent six months in the underworld, corresponding to autumn and winter on earth, and in the other six she returned to earth, which blossomed again in spring and summer). This story was often depicted on pinakes because the Greek colonies in southern Italy were very attached to the cult of Demeter: the fantastic animals, in this case, are the winged horses of Hades, which drive the chariot in which the lord of the underworld travels to earth to abduct Persephone (depicted looking into Hades’ eyes, facing him) and take her with him to his realm. The pinax in question comes from ancient Locri, which was one of the most important cities of Magna Graecia.

The Sirens of Greek mythology were not the beautiful half-woman, half-fish creatures we all have in mind: this iconography did not spread until the 9th century. In ancient times, mermaids had the face of a woman and the body of a bird, and they fascinated not so much because of their physical appearance, since they were creatures considered monstrous, but because of their very sweet voice capable of singing melodies that enraptured sailors (the episode ofOdysseus who in theOdyssey has himself tied to the mast of the ship in order to listen to the mermaids is famous). The mermaid in the National Archaeological Museum in Reggio Calabria is no exception, depicted on an alabastron, or vase that was used to store oil, perfumes, ointments, and balms and was very elongated in shape and was usually made of alabaster (hence the name). The one in the Reggio museum is a rather ancient specimen, dating from the 6th century B.C. and coming from the sanctuary of Scrimbia.

An interesting arula is the one decorated with the episode of Heracles and Acheloos preserved at the National Archaeological Museum in Reggio Calabria. Heracles, the heroic demigod of prodigious strength, is depicted naked, on his knees, trying to hold back the momentum of Acheloos’ attack: the latter was a river deity, son of Oceanus, and had transformed himself into a bull with a human face. In the fight with Hercules, Acheloo first turned into a snake, then into a bull (as we see him in the arula of Reggio Calabria), then into a dragon, and finally into an ox-headed man. Heracles engaged in a struggle with him because Acheloos was opposed to his marriage to Deianira: seeing himself defeated after, following the last transformation, Heracles snatched away a horn from him, the river god agreed to the marriage, on the condition, however, that the horn would be returned to him, further reciprocated by Heracles with a horn from the goat Amalthea, from which the famous cornucopia was born. Also according to the myth, from the drops of blood that Acheloos lost during the fight, the sirens would be born. Originally, the scene depicted on this arula was colored: tiny traces of the original coloring are preserved on Heracles’ body, beards and hair.

Speaking of mermaids, to understand how the Greeks saw them, perhaps one of the best and best-preserved examples is the mermaid-shapedaskos from the necropolis of the Murgie di Stringoli (ancient Petelia) and now in the National Museum in Crotone. An askos was a small vase that contained mostly oil and was used to fuel lamps and oil lamps. The peculiarity of theaskos lies in the fact that it was often made in the form of an animal: many have been found in Crotone, and the one with the mermaid in the National Museum is one of the finest and most beautiful in all of Magna Graecia. Since theaskos in question comes from a funerary context, we also find depicted on it the soul of the deceased, in the part of the handle: according to Greek mythology, in fact, sirens, with their melodious song, consoled the souls of the dead and accompanied them to the afterlife.

This particular vase, which has been preserved in fragmentary form, depicts a mermaid holding a dove: this is an image not so uncommon among finds in Calabria, and it is linked to funerary rites. It was mentioned above that mermaids, with their singing, accompanied the souls of the deceased to the afterlife to console them with their melodies: in this case, since the cult of Aphrodite, the goddess of beauty, was particularly widespread in Locris, the mermaid offers a dove, a bird sacred to the deity, in what was probably an ex voto intended precisely for Aphrodite. In classical antiquity, ex votos might not only have been images “for their own sake,” so to speak, but also everyday objects, as in the case of the Vibo Valentia mermaid, which was nothing more than a vase configured with this image. The work dates back to the 6th century B.C. and is made of terracotta.

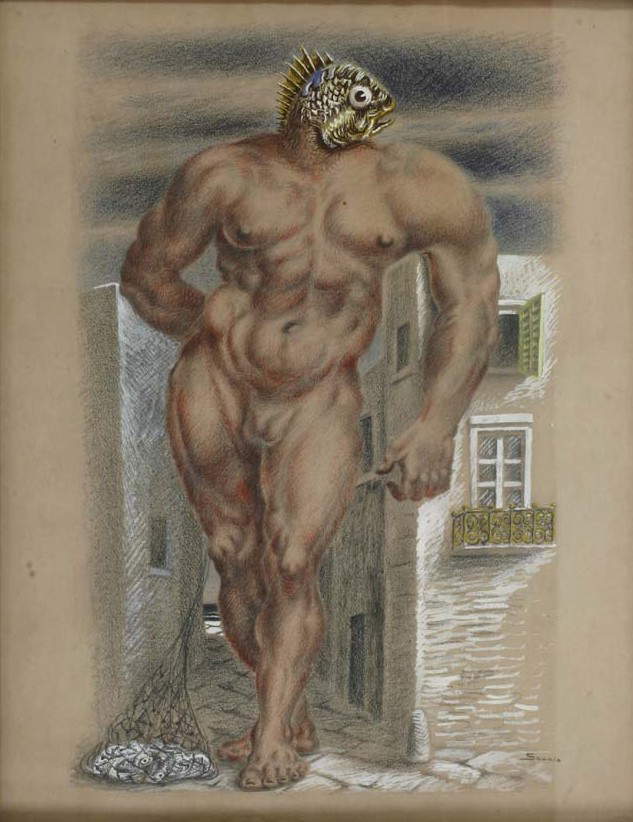

Alberto Savinio, brother of Giorgio De Chirico (he chose to change his surname precisely so as not to be confused with his brother), was one of the most original and innovative Italian artists of the early 20th century, the most “surreal” of the metaphysical artists. This is well illustrated by his Neptune the Fisherman preserved at the National Gallery in Cosenza: the god of the sea is ironically described as a sinewy man with a fish head and pulling a net with what he has just caught in it. It is Savinio himself who speaks of this work of his, probably painted in 1932 after his Paris sojourn, in the 1943 short story Walde Mare: “On summer afternoons, when the sun was setting on the horizon and on the land the shadows were getting longer and longer [...] Neptune would disembark on the pier and go and sit at the Caffè Lubiè to enjoy some fresh air. He liked lucùm, which in their great variety and under the sugar powdering have all the colors of the iris, and certain round, chocolate-painted sweets [...] Mr. Lubié, the owner of the establishment, would have gladly renounced the honor of novering among his customers a god, and would have been pleased that Neptune moved from time to time, he and his trident, to the nearby Tombasi café, run by his enemy and rival Pelopida Zanakakis.” So, with a shift typical of Alberto Savinio’s art, the powerful god of the sea becomes a humble fisherman who returns from his business and indulges in a stop at the café, wearing a fish head to sanction the character’s complete identification with the element associated with him.

Perhaps not everyone knows that the father of Gian Lorenzo Bernini (the great Baroque sculptor who created the Fountain of Rivers, theApollo and Daphne in the Borghese Gallery and many other important sculptural groups of the 17th century), namely Pietro Bernini, was himself an interesting and original sculptor. This is also demonstrated by the Laocoon preserved at the Pinacoteca Civica di Reggio Calabria, which reproduces the famous group that was found in 1506 on the Esquiline Hill in Rome and is now in the Vatican Museums: according to myth, Laocoon was a Trojan priest who had advised his fellow citizens against accepting the horse received as a gift from the Greeks (it was he who uttered the very famous phrase “Timeo Danaos et dona ferentes,” or “I fear the Greeks even when they bring gifts”): in response the goddess Athena, who was protecting the Achaean army, sent him from the sea two monstrous sea serpents, Porcete and Caribea, which gripped Laocoon and his sons and dragged them into the sea. The Laocoon in the Reggio Calabria museum has been attributed to Bernini because of a softness in the faces reminiscent of some earlier achievements, and because of the way the sea serpents are made, which envelop Laocoon’s bodies of his sons with great naturalness.

|

| Animals and fantastic places in the museums of Italy: Calabria |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.