Animals and fantastic places in Italy's museums: Sardinia

The journey to discover animals and fantastic places in Italian museums reaches its fifteenth stage: let’s find out today what creatures are hiding in Sardinia. The project is conducted by Finestre sull’Arte in collaboration with the Ministry of Culture with the aim of letting people discover museums from a different point of view, remembering that museums are safe and suitable places for everyone. So let’s set off on our journey around the Mediterranean island and see what fantastic animals we found!

1. The dragon of St. Margaret at the National Picture Gallery of Cagliari

According to hagiographic tradition, St. Margaret of Antioch was a Christian virgin who, for rejecting an attempt at seduction by the prefect Ollarios, was denounced by him as a Christian and then imprisoned. During her imprisonment, the devil appeared to her in the guise of a huge dragon; Margaret, however, managed to defeat him simply by praying, and thus the dragon became the animal that always accompanies her depictions. Here, we see him represented as a large lion-headed reptile. The panel is taken from the predella of the Retablo dell’Annunciazione, the oldest work in the pictorial collection of the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Cagliari: the Retablo was made between 1410 and 1412 by Spanish painter Joan Matés for the chapel of the Annunciation in the now-defunct church of San Francesco in Cagliari’s historic Stampace district.

2. The winged demon from the National Archaeological Museum in Cagliari.

This Nuragic bronze statuette depicts a winged demon and was found in the 1930s in the locality Su Casteddu de Santu Lisei in the countryside of Nule in the province of Sassari. Archaeologist Doro Levi, then director of the Cagliari Museum and Superintendent of Antiquities of Sardinia, recovered this small bronze that stands out for its decidedly rare, if not unique, appearance. The work depicts a quadruped with equine hooves and a twisted tail, with a human face and stubby arms. On the human head are a pair of short bovine horns and a headdress with an imposing plume. A very ancient work (dating from the Iron Age, a period between the 10th and 7th centuries B.C.), like all Nuragic bronzes it was an ex voto offered as a gift to a deity. The National Archaeological Museum in Cagliari holds one of the richest collections of these particular objects, made using the lost-wax casting technique, of which they constitute one of the earliest attestations.

3. Sea monsters in the sarcophagus of the Nereids at the National Archaeological Museum in Cagliari.

According to Greek mythology, the Nereids were sea nymphs, daughters of Nereus and the oceanine Doris. In ancient works they are often depicted in processions accompanying Poseidon, god of the sea, complete with sea monsters, as in the case of this sarcophagus, known as the “Sarcophagus of the Nereids,” probably from the eastern necropolis of ancient Karalis (Cagliari). The deceased is depicted in the center of the front of the sarcophagus inside a shell-shaped clypeus in the act of playing a lute, an element denoting her membership in a high social class. The base of the sarcophagus is moved by sea waves among which swim and move various creatures that inhabit the sea: we see tritons, cupids, the Nereids themselves and other fantastic creatures that make up a thiasos scene (a procession that celebrated a deity), to be precise a marine thiasos, often depicted in sarcophagi of the Imperial Roman age.

4. The sphinx at the National Archaeological Museum in Cagliari.

The sphinx, the mythical animal with the body of a lion and the head of a woman, according to various ancient cults was placed as a guardian of sacred environments, or necropolis. And from a sacred environment linked to oriental cults, which were particularly widespread in the Roman imperial age, also comes this splendid sphinx in pink granite from Egyptian quarries, found in the area of the Botanical Garden of Cagliari, in an area where several fountains and nymphaea were located in ancient times, set between the city amphitheater and a residential neighborhood, of which the dwellings known today under the name “Villa of Tigellio” are still preserved. The sculpture was made in Ptolemaic-era Egypt and was brought to Sardinia later, specifically to decorate a sacred place. It is one of the most “historical” pieces of the National Archaeological Museum of Cagliari: it was in fact part of the first nucleus of artifacts with which the museum was established in the early 19th century, but already at the end of the previous century the scholar of Sardinian history Ludovico Baille (Cagliari, 1764 - 1839) spoke of a sphinx that was located on the steps of the Cathedral of the Sardinian capital. He was probably referring precisely to the sphinx now in the National Museum.

5. The griffin and winged horse of the pluteus at the National Archaeological Museum in Cagliari.

A unique pluteus from the mid-10th century, decorated with the figures of a griffin and a pegasus, or winged horse: this is the one found today at the National Archaeological Museum in Cagliari. In architecture, a pluteus is a rectangular slab balustrade, which in ancient times could be ornamented. Such is the case with this object, a liturgical ornament was found in 1966 in the waters of the islet of San Macario, not far from the small church of Sant’Efisio in Nora, for which some scholars believe it was intended. The griffon is a mythological bird with the body and legs of a lion and the head of a bird of prey, and it faces the pegasus in front of the tree of life. These are animals that recur in Byzantine sculptural production, to which this pluteus must be referred: the griffin is symbolic of Christ, since this fantastic creature is composed of an animal of earth and an animal of heaven, thus signifying the earthly and heavenly nature of the son of God. The same mediating role between heaven and earth is played by the winged horse, for the same reasons.

6. The goddess Tawaret in the amulet from the National Archaeological Museum in Cagliari.

In Egyptian mythology, Tawaret (also known as Tueret, Tauret, Taweret) is a goddess with the body of a woman and the head of a hippopotamus, linked to female fertility cults: in fact, she was the protector of pregnant women and children. In addition, she was considered the mother of the sun, and was therefore connected to the symbolism of rebirth. Her cult also spread outside Egypt: in fact, she was also worshiped in Crete, Nubia, and among the Phoenicians. She was therefore often depicted on votive and devotional objects, such as this amulet that depicts Tawaret according to her classical iconography, that is, with a prominent belly, pendulous breasts, and the head of the great African pachyderm. Images drawn from the Egyptian pantheon were widespread in the Phoenician and Punic worlds, where amulets accompanied daily life and death, appearing in conspicuous numbers in grave goods.

7. Satyr mask from the National Archaeological Museum Antiquarium Turritano.

This satyr mask is one of the most unique objects in the Porto Torres museum. It was found in 2003 in the area of the Maetzke Baths in Porto Torres, an ancient thermal facility (also known as the “central baths”) from the 3rd century AD named after the archaeologist who discovered them during a 1958-1961 excavation, the Tuscan Guglielmo Maetzke (Florence, 1915 - 2008). Satyrs were figures with half the body of a man and half (the lower one) of a goat: according to Greek mythology they inhabited the woods, were skilled at playing the flute, were characterized by strong sensual appetites, and accompanied the god Dionysus in his processions. Sometimes, to give greater evidence of their bestial nature, artists tended to exaggerate the features of their faces: this is also evident from this mask, where the satyr’s face takes on a feral and grotesque appearance, with huge eyes, a wide and frightening mouth, and pointed ears like those of a goat. The mask was probably part of a fountain, of which it was a decorative element: we can imagine water gushing from its mouth.

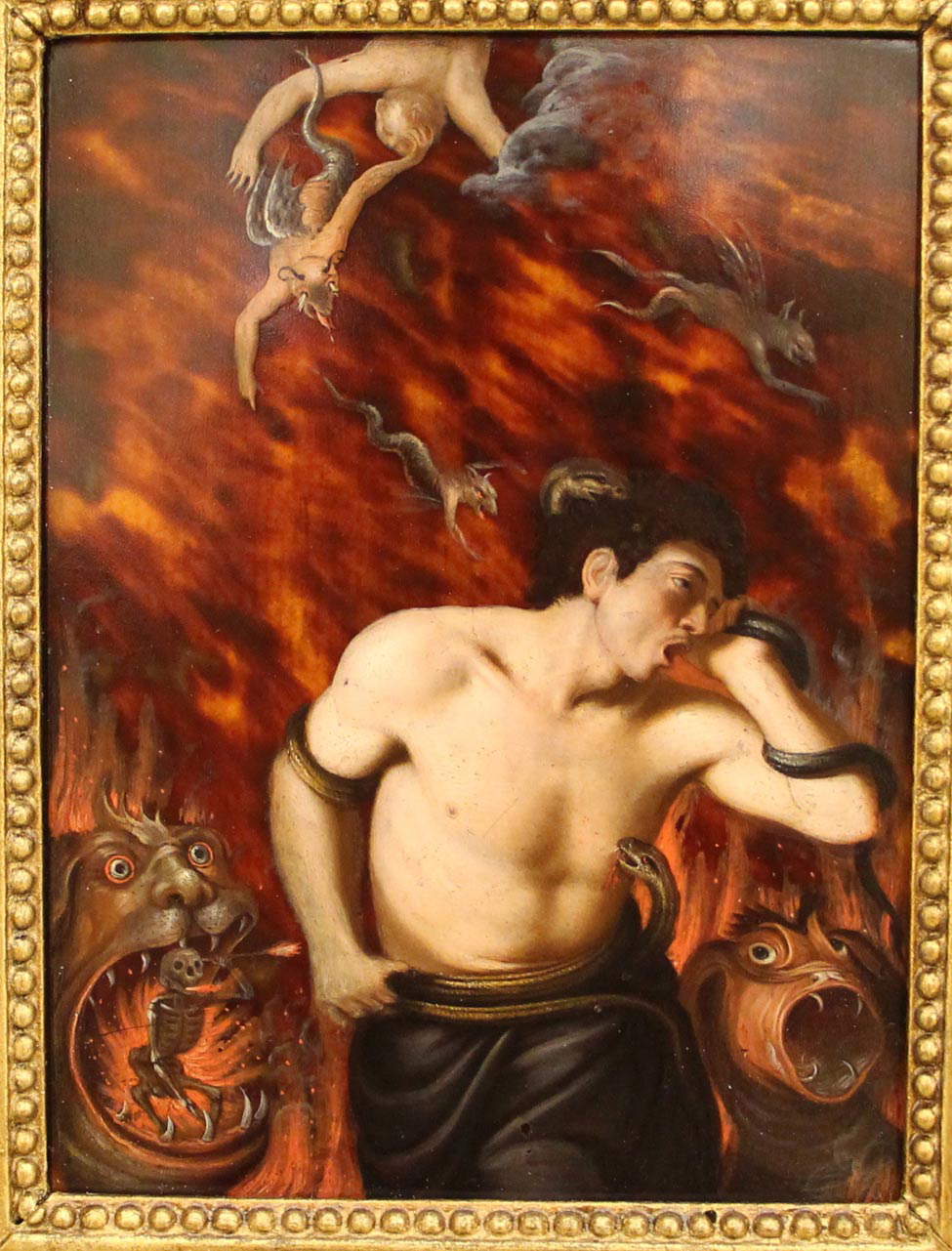

8. Lionello Spada’s damned soul from the National Picture Gallery of Sassari.

An object of small dimensions (16 by 13 centimeters) but extremely peculiar: the author, the Emilian Lionello Spada (Bologna, 1576 - Parma, 1622) in fact painted his Anima dannata on the carapace of a turtle, exploiting the texture of the animal’s shell to give the relative the impression of the flames of hell enveloping the painting’s protagonist, a man condemned to the fire of the underworld, already enveloped by a menacing snake. The fantastic creatures are those that torment him, painted around his soul: they are the demonic beings of the underworld, who take the form of devils (especially at the top) but also of monsters with an animalistic appearance, such as those on either side of the soul that resemble enormous fish.

9. The loop with silenus from the National Archaeological Museum in Nuoro.

The National Archaeological Museum “Giorgio Asproni” in Nuoro preserves this loop attachment (thus a handle that was attached to a vessel that has been lost) that ends with the head of a Silenus, an ancient woodland creature with the body of a man and the legs of a horse (unlike centaurs, Silenuses had only two legs, while they differed from satyrs in that the latter, as mentioned above, had goat legs, and could be depicted with pointed ears like those of goats). This object comes from an excavation in Orgosolo, in the locality of Orolù, not far from Nuoro. It is a very valuable object because, together with other finds at the same site, it has testified to how, in Roman times, even the innermost areas of Barbagia were involved in the production, or at least trade, of objects of great craftsmanship (such as this ansa with silenus): in fact, until before this discovery, it was believed that in the most remote areas of Barbagia the Roman presence had never taken root.

10. Fantastic places: the prenuragic altar of Monte d’Accoddi.

Near Sassari, not far from the sea, there is a place that has no equal not only in Sardinia but in the entire western Mediterranean: it is the pre-Nuragic altar of Monte d’Accoddi, an archaeological site dating from 4000-3650 B.C. but later expanded by the people of the Abealzu-Filigosa culture, which developed in pre-Nuragic Sardinia in the Copper Age. The altar is the main wonder of the site and has a stepped structure similar to that of Mesopotamian ziggurats of the third millennium B.C.E.: the structure we see is from about 2800 B.C.E., when the temple was rebuilt in place of an earlier one destroyed perhaps by fire. Made entirely of stone, with large irregular blocks that give it a raised form useful for highlighting its function as a mediation between heaven and earth, the altar of Monte d’Accoddi was the place where local communities gathered to perform fertility-related rites.

|

| Animals and fantastic places in Italy's museums: Sardinia |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.