Animals and fantastic places in Italy's museums: Lazio

After Lombardy and Campania, Finestre sull’Arte ’s journey to discover the animals and fantastic creatures depicted in the works of Italian museums and the fantastic places one encounters as one travels along our peninsula makes a stop in Lazio. Between Rome, Viterbo, Sperlonga and Ostia we found, once again, fantastic creatures and places that fascinate young and old alike, reminding you that museums and places of culture are safe and suitable for spending peaceful moments in the company of your family and children. The project is conducted in cooperation with the Ministry of Culture. Let’s get started!

1. The centaurs in the Wedding of the Centaurs at the H.C. Andersen Museum in Rome.

Not far from Piazza del Popolo in Rome stands the Hendrik Christian Andersen Museum, in a small building built between 1922 and 1925 by the naturalized Norwegian-American sculptor Hendrik Christian Andersen (Bergen, 1872 - Rome, 1940) who lived in Rome from the late 19th century until his death. The building also housed his sculpture studio on the ground floor, while he lived on the second floor. Now a house-museum, the building houses the large collection of the artist’s works: more than two hundred large, medium and small sculptures in plaster and bronze, over two hundred paintings and more than three hundred graphic works. Among the sculptures is a plaster statue depicting the wedding of the centaurs in which two half-man, half-horse creatures from Greek mythology are embracing and kissing each other with loving transport on a carpet of grasses and flowers. Their figures, joining in the embrace, become almost one. The centaurs derive their name from the progenitor Centaur, son of the Lapith king Ission, who constituted the oldest tribe in Thessaly. During a banquet, Ission attempted to seduce Hera; Zeus, realizing the latter’s intentions, transformed a cloud, Nephelah, into the likeness of Hera so that the drunken Ission did not notice the trap. From the union of Ission and Nephelah was born Centaur, who joined the mount Pelion mares and became the progenitor of the Centaurs.

2. The Head of Medusa in the National Roman Museum

The National Roman Museum in Rome’s Palazzo Massimo houses a beautiful head of Medusa, one of the three Gorgon sisters and also the most famous, characterized by snakes instead of hair and a gaze that petrified anyone who looked at her. She is depicted with large eyes designed to enchant, her mouth closed in a serious expression ready to beguile, as opposed to the open mouth with which she is usually depicted. Her hair is moved by the wind and small wings sprout on her head. The piece is made of bronze and was probably used as a decoration in Caligula’s first ship found at the bottom of Lake Nemi: the ships were in fact adorned with finely crafted bronzes, golds and gems, and statues, an expression of pageantry aimed at celebrating the emperor’s wealth and worship.

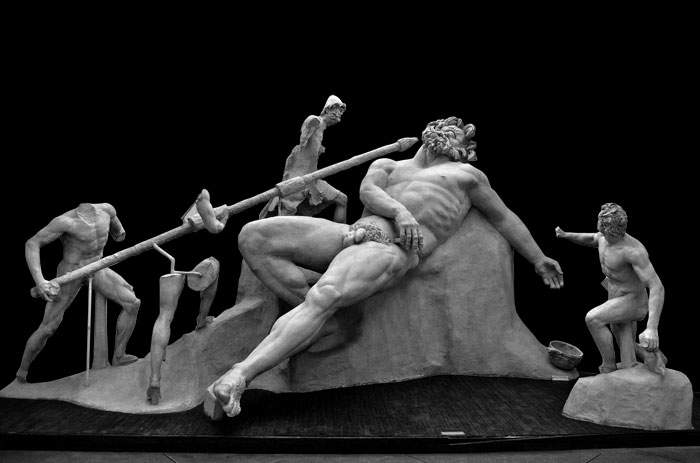

3. Cyclops Polyphemus in the sculptural group of Ulysses blinds Polyphemus at the National Archaeological Museum in Sperlonga

The National Archaeological Museum in Sperlonga is home to the colossal sculptural group of Polyphemus, which tells the story of the Odyssey in which the hero Odysseus, during the long journey back from the Trojan War, surrounded by his fellow sailors, blinds the giant Polyphemus with a long pole with a glowing tip, who, as a cyclops, a figure from Greek mythology, has only one large eye on his forehead. In order to succeed, Odysseus and his companions got him drunk (in fact, one of the sailors holds lotres of wine in one hand) and so the cyclops fell into a long deep sleep lying on a rock: Odysseus took advantage of the right moment to blind him and thus succeed in escaping from the cave in which the cyclops had imprisoned them. Also on display at the Sperlonga museum is a proposed reconstruction of the sculptural group, starting with existing fragments found during excavations in the area of Tiberius’ villa to give a complete idea of what the colossal sculpture present in the ancient villa must have looked like. The sculpture is probably referable to Athanodoros, Hagesandros and Polydoros of Rhodes, whose signature is on the other large sculptural group in the museum, that of the Scylla attacking the ship of Odysseus and his companions as they pass through the Straits of Messina. These same masters made the famous Laocoon group exhibited in the Vatican Museums. The theme of Ulysses is very common in this area, since since Roman times it was believed that the promontory to the north was the island of the sorceress Circe where Ulysses stopped for over a year before resuming his journey home.

4. The winged dragon in Marcello Provenzale’s Orpheus at the Borghese Gallery.

Among the many animals surrounding Orpheus, intent on playing the lyre from his arm as he sits in the shade of an oak tree, one recognizes a golden-colored winged dragon with bat wings, webbed legs, and snake tail, and above him perched on a twig of the great tree is an eagle. The two animals refer to the coat of arms of Cardinal Scipione Borghese, commissioner of the mosaic completed in 1618 by Marcello Provenzale (Cento, 1575 - Rome, 1639) now on display at the Galleria Borghese in Rome. According to Ovid’s Metamorphoses, all the animals, including reptiles, birds and felines, were attracted by Orpheus’s sad song intoned for the loss of his beloved Eurydice, who clustered around him in comfort: even the hearts of the fiercest beasts softened to the sound of the sad song. In the background are glimpses of the flames of the underworld, where, according to the tale, the young shepherd had descended to bring back to earth the beautiful nymph Eurydice who had died of a snake bite. The attempt was unsuccessful because the soul of the beloved was sent back to the afterlife forever after Orpheus had turned toward her on the threshold of the underworld, not respecting the prohibition imposed on him by the god of the afterlife, Hades.

5. The centaurs in Giorgio De Chirico ’s The Struggle of the Centaurs at the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rome.

Prior to his metaphysical season, Giorgio de Chirico (Volo, 1888 - Rome, 1978) produced an oil on canvas depicting a Struggle of Centaurs in 1909, a work that became famous today and is preserved at the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rome. This painting derives directly from paintings by Arnold Böcklin (Basel, 1827 - San Domenico di Fiesole, 1901): explicit quotations from the latter’s works were recognized, as De Chirico was a great admirer of the Swiss painter, and in particular the atmosphere with the deep blue sky streaked with white, the excitement of the scene, and the violence expressed by these half-man, half-horse monsters totally express the drama the artist wanted to bring to the canvas. Although inspired by Böcklin, De Chirico represented the struggle of the centaurs with much darker strokes, as a struggle between figures representing the original forces of nature and therefore instinctive. Probably the Swiss painter had opened his eyes to a primordial world, where the bestial element is dominant and where life submits to the violence of nature, transcending feeling and reason.

6. The Gorgons in the Domus of the Gorgons in Ostia Antica.

In the Archaeological Park of Ostia Antica is the Domus of the Gorgons, which owes its name to the mosaic depiction, inside room 17, of a large gorgoneion accompanied by the words “Gorgoni bita,” which has been interpreted as “Evita Gorgo!” The figure is depicted inside a rectangle with bichromatic, black and white geometric patterns that draw a rhythmic decoration. The Gorgons were daughters of Forcus and Ceto and were three sisters (Steno, Euryale and the more famous Medusa): monsters of Greek mythology, they had golden wings, bronze hands and snakes instead of hair and had the power to petrify anyone who looked into their eyes. For this reason, all contact with these creatures was to be avoided. The Gorgon’s head was often depicted as a decorative motif in ancient buildings as a mask figure with an open mouth and hair mixed with snakes; in the Ostia Antica mosaic the entire face is surrounded by serpents, the mouth is closed, and long wings sprout from her head with curly hair.

7. Fantastic creatures in the frescoes of the Altoviti Room in the Palazzo Venezia in Rome

The Altoviti Room in the Palazzo Venezia Museum in Rome takes its name from the frescoes that were originally created in the Altoviti Palace and then later mounted here in 1929. Florentine-born banker Bindo Altoviti commissioned Giorgio Vasari to paint frescoes in 1553 that were meant to celebrate the family’s wealth and the wedding of Giambattista Altoviti and Clarice Ridolfi; following the Tiber Law of 1876, masonry embankments of the river began to be built and thus numerous buildings were destroyed, including Palazzo Altoviti, but Vasari’s frescoes were detached and mounted on canvases to preserve them. The Altoviti vault was in fact reassembled by the painter Torello Rupelli, who integrated and contextualized them within the room. The large central oval depicts Homage to Ceres, goddess of fields and harvest as well as abundance. On the sides two panels depict through personifications Florence crowning the Arno and Rome crowning the Tiber, accompanied by the symbols of the cities, namely the Marzocco lion with the lily and the She-wolf with Romulus and Remus. Surrounding them are grotesques with putti games, a tussle of tritons and a tussle of centaurs, while the twelve months of the year are depicted at the base of the vault.

8. The wolf-man in the Etruscan plate by the painter of Tityos at the National Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia in Rome

The National Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia in Rome preserves a black-figure ceramic plate on foot datable between 540 and 510 B.C. and attributable to the painter of Tityos. It has a diameter of twenty centimeters, like a modern dessert plate but bottom and is almost ten centimeters high. Along the rim runs a decoration of alternating palmettes and lotus flowers, while the inner surface has a central roundel in which a single figure is depicted: that of a wolf-man, perhaps a deity of the underworld. He is facing to the left, with his body in front and his head in profile; his limbs are bent, to fit the space in which he is contained. It is naked, with its black body covered with hair rendered in small white strokes: certainly the body is that of a man, but it has sharp claws and the head is that of a wolf, the ears straight and the mouth open from which the red tongue comes out. Gold bracelets are noticeable on its forearms. It is a kind of Etruscan werewolf. Around it, in the circular band, three other figures are painted proceeding counterclockwise: a centaur, a man with bow and staff, and finally a woman. The scene is recounted in Book Four of the Histories of Diodorus Siculus in which he relates that Heracles and his wife Deianira came upon the centaur Nessus on the bank of a river; the latter, having fallen in love with the woman, had tried to take her by force. For this Heracles shot him with an arrow and killed him. The scene therefore depicts the moment when Heracles is preparing to strike Nessus and the latter is seen turning back and with his right hand clutching a sapling improvising a weapon. The dish with Heracles, the abduction of Deianira and the wolf-man was found in the Osteria necropolis at Vulci during the Hercle Society excavations of 1961-1963, and is part of the grave goods in tomb 177.

9. Unicorn in Luca Longhi’s Woman with Unicorn at the National Museum of Castel Sant’Angelo.

In the center of the scene, in the foreground, a maiden with her gaze turned toward the viewer is seated next to a unicorn and points to it, inviting the viewer to place his or her attention toward the creature. In the background is a clear landscape with bucolic features. The young woman, portrayed here in heraldic garb, is probably Giulia Farnese, sister of Pope Paul III: the Virgin with the Unicorn had in fact been a symbol of the Farnese family for two generations when the Romagnolo painter Luca Longhi (Ravenna, 1507 - 1580), a family portraitist and an artist strongly influenced by the Leonardo manner, particularly in his landscapes and luministic rendering, produced this painting between 1535 and 1540, now housed in the National Museum of Castel Sant’Angelo. The depiction of a maiden next to the unicorn was widespread and was an allegory of chastity, since according to the tale contained in the Physiologus only a pure virgin was able to tame a unicorn. In addition to the coat of arms of the Farnese family, Longhi’s portrait thus also recalls the concept of the girl’s purity. However, it is a work of postmortem celebration, as it was executed at the behest of Giulia Farnese’s family members after her untimely death in 1524. It is known that the composition is taken from a drawing by Leonardo da Vinci (Anchiano, 1452 - Amboise, 1519) preserved in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

10. Fantastic creatures at the Sacred Wood of Bomarzo (Viterbo).

It is two monumental sphinxes that greet anyone who enters the Sacred Wood of Bomarzo, in the province of Viterbo, but along the path immersed in nature there are many fantastic creatures and unusual buildings that one encounters that make young and old alike gasp in wonder: the Proteus-Glaucus, an aquatic being drawn from Greek mythology associated with its ability to shape-shift, the giants Hercules and Cacus, the winged Pegasus, the god Neptune, the three-headed monster Cerberus, Medusa, the echidna (a monster with a woman’s body and a snake’s body), the Dragon, the leaning house where the sense of balance is put to the test, the sleeping Nymph, and first of all, the great gaping-mouthed Orc that invites visitors to enter its interior to forget all evil thoughts. It was probably for this reason, to free the mind and to “vent the heart,” although the true meaning of the entire path remains unknown to this day, that Pier Francesco Orsini, known as Vicino (Rome, 1523 - Bomarzo, 1585), conceived and had this marvelous place built in the mid-sixteenth century. A place to find serenity after the untimely death of his beloved wife Giulia Farnese in 1560. It fascinated famous figures such as Goethe and Salvador Dalí, and it was here that Niki de Saint Phaille found inspiration for the famous Tarot Garden. Today the Sacred Wood of Bomarzo is one of the most evocative parks in Italy.

|

| Animals and fantastic places in Italy's museums: Lazio |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.